By Celia Kitzinger, 14th December 2025

At a private hearing in July 2024, Mrs Justice Morgan made a decision to refuse a Health Board’s application to remove a severely autistic 18-year-old woman (P) from the family home without notice to the family and using force if necessary. The judgment is published here: Hywel Dda University Health Board v P & Anor [2024] EWCOP 70 (T3).

The Health Board’s application was made in order to secure a series of assessments relating to P’s capacity, treatment, and care needs. According to the Health Board, these assessments couldn’t be done at home because P’s mother was exerting “undue influence” over P. The key witness upon which the Health Board relied was a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, named in the published judgment as Dr Amanda Bayley, who gave evidence, accepted by Morgan J, that the mother was blocking professional access to P in order to frustrate P’s wish to live somewhere other than in the family home.

Dr Bayley had also submitted evidence that the mother (she’s ZJ in the judgment and I’ll call her “Zoe”) posed a “flight risk”. On the basis of that evidence, several senior judges (possibly Theis J, certainly Cohen J and Morgan J) had made orders that hearings should be “without notice” to Zoe for fear that, if Zoe knew about the application to remove P, she would abscond with her daughter, and the opportunity to assess P’s needs could be lost forever. The alleged “flight risk” meant that Zoe had been deliberately excluded from the proceedings up to and including the July 2024 hearing. Zoe had been informed that the Court of Protection would be involved at some point, but the intention was to avoid her knowing that hearings were already taking place.

As with closed hearings generally, this led inevitably to procedural unfairness. The decision to hold closed hearings meant that the judge was having to decide on Hywel Dda UHB’s application to remove P from the family home without either mother or daughter having had any input into the proceedings. Zoe was not able to give witness evidence or to be joined as a party or to seek legal advice. A Litigation Friend (the advocate Beth Owen) was appointed for Zoe’s daughter, but there had been no contact between the Litigation Friend and P (because that would have alerted Zoe to the proceedings) and so the Litigation Friend was not in a position to report on P’s wishes and feelings at the hearing[1].

The Health Board’s application was opposed both by P’s Litigation Friend, who “strongly opposes any order which has the effect of removing P from her home without evidence of her wishes and feelings” §8), and by the local authority, Ceredigion County Council, who “wish to work openly and honestly with the family” (§6).

After hearing conflicting evidence from the professionals, the judge refused the application. Instead, she made orders that Zoe must allow professionals into the family home to assess P, and must not impede or interfere with their assessments. She also ordered that Zoe should be informed about the next hearings (to deal with the bests interests decisions consequent upon assessment and with deprivation of liberty safeguards) and invited to participate in them.

The published judgment is the formal public version of what happened to Zoe and her daughter, as told from the perspective of a Court of Protection judge in July 2024. Like all judgments, it’s a selective and incomplete version of events. It captures the judge’s view of the “facts” at a particular moment in an unfolding story, based on evidence put forward by the public bodies. It doesn’t – and couldn’t – represent Zoe’s version of events because she’d been excluded from the hearing. And after the judgment, there was new evidence before the court from an independent expert appointed to assess P – and that new evidence cast a very different light on the situation.

This blog post records Zoe’s voice – missing from the July 2024 judgment – and reports on how the proceedings continued through several further hearings, and eventually concluded in November 2024, with long-lasting consequences for Zoe, for P and for the family. There are lessons to be learnt from the July 2024 judgment, but only if we have the bigger picture.

My involvement

By the time of the July 2024 hearing, I was already in contact with the family at the centre of this case. Fearing that the Health Board wanted to take her daughter away, Zoe had contacted the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, nearly a year earlier, wanting information about the court’s procedures and how she could best protect her daughter.

The Project was not set up to provide support or information to family members involved in, or anticipating, Court of Protection proceedings. We are a small group of members of the public (none of us lawyers or journalists) committed to supporting the judicial aspiration for transparency in the Court of Protection by observing and blogging about hearings, and encouraging others to do likewise: we are unpaid volunteers. (For more information see our website: “About the Project” and “Meet the Team”.) Inevitably, though, desperate family members contact us for help. We are clear about the limits of what we can offer – but as some of us have our own family experience of the court, and as we have developed an increasing understanding of normal court procedures, we do sometimes offer informal support and information. It was on that basis that I was in regular contact with the mother in this case, initially by email, and later by video-calls as well, from August 2023 onwards. So, I approach writing about what happened in this case not only as a court observer but as someone who has been in contact with the protected party’s mother before, during and subsequent to these proceedings.

Closed hearings

Although I knew about the July 2024 hearing, I did not observe it – and I didn’t realise at the time that it was about Zoe’s daughter. Nor, of course, did Zoe. I saw the hearing in the public listings where it was labelled “private”. In fact, as we now know, it was more than that – it was taking place, by order of the court, without formally notifying either P or P’s mother. Hearings like this are commonly called “closed”, “without notice”, or “ex parte”[2]. This hearing, on 16th and 17th July 2024, was the third in a series of hearings in this case (COP 14216699) from Spring 2024 onwards, from which the mother was excluded by order of the judge .

Closed hearings represent a significant departure from normal judicial practice – and from most people’s understandings of natural justice. Even when they’re the right thing to do, they can cause harm to the excluded party, and even good decisions made in secret can leave the people excluded from the process feeling profoundly wronged. Judges have recognised this – for example by highlighting the importance of considering the impact of making a ‘without notice’ order on “… the rights, life, and emotions of the person against whom it is granted” (§41 B Borough Council v S & Anor [2006] EWHC 2584 (Fam)). Since observers are usually not permitted at closed hearings[3], they also defeat the judicial aspiration for transparency, and they add to public distrust of the law.

Closed hearings also necessarily restrict the evidence before the judge: in this case, the judge was not able to hear evidence from Zoe or to learn anything about P’s values, wishes, feelings and beliefs. By the final hearing in November 2024 (which I did observe), it was apparent that a lot of the “facts” reported in the published judgment are simply wrong. Crucially:

- Zoe was not a flight risk – although the judge was not made aware of it at the time, Zoe already knew about the proceedings, believed (correctly) that their purpose was to remove her daughter, and had emailed the Health Board asking to be made a party (that email was not disclosed to the court until after the July 2024 hearing).

- There is no evidence of Zoe having undue influence on, or being coercive and controlling towards, her daughter (according to Dr Mike Layton, the independent psychiatric expert subsequently appointed by the court, whose evidence was accepted by the judge).

- In sometimes refusing appointments with her daughter, Zoe was seeking to act in her daughter’s best interests, because P was finding them so hard, and having ‘meltdowns’ as a result. At the final hearing in November 2024, the judge said she was “very struck by Dr Layton’s observation that continuing and multiple assessment was causing active damage to P”. Zoe had been making exactly that observation to me for more than a year, but since she’d been excluded from the July 2024 hearing, she’d been unable to give her evidence to the judge. On the basis of Dr Layton’s evidence about the assessments causing harm to P, the parties agreed (in advance of the November hearing) that all further assessment should be paused.

- P did not want to live away from the family home – even suggesting this as a possibility caused her significant distress (said the independent expert, Dr Layton).

At the November 2024 hearing, the judge referred to a “sea change” in the evidence before her, and the Health Board has subsequently apologised to Zoe for the way the case was brought to court. It was clearly the view of the judge that Hywel Dda University Health Board should learn some lessons from what had gone wrong in this case – and I quote from what she said below. But – although both Zoe and I have requested one – there is no published judgment from the November hearing. The only public record of what happened to her family is the “false narrative” (Zoe’s term) of the July 2024 judgment. The facts that had emerged by the final (November) hearing are not in the public domain.

This means that the precedent-setting published judgment of a Tier 3 judge comprises legal analysis of evidence that the judge herself subsequently discredited in a later hearing. The judge corrected the record orally but not via a written judgment. It’s the uncorrected version that stands as the basis on which lawyers and others learn lessons for the future. For example, the published judgment was cited recently in a webinar by lawyers at Kings Chambers as an example of an injunction used in “a very extreme situation where other methods haven’t worked” and “you need injunctions to complete the assessment”[4] – which is a correct reading of the judgment but an incorrect reading of the actual situation and the facts behind the judgment, as they eventually emerged in subsequent hearings.

In my view, the lessons (for the Court of Protection) to learn from this case are not about when and how to impose injunctions on family members. The more compelling lesson is that the administration of justice is not well served by excluding parties from hearings. At the most basic level, it means you risk getting your facts wrong. It also undermines public confidence in the justice system. The Court also needs to be better informed about systems-generated trauma and how it affects those caught up in proceedings.

For Zoe, exclusion from her daughter’s Court of Protection proceedings between February and July 2024 has left her with a devastating feeling of injustice. She no longer trusts in the law to protect her family. She’s incredulous that it’s actually lawful for judges to make decisions about vulnerable people without any input from them or from the relatives who care for them. She says: “I feel my voice and P’s voice were stolen”.

She feels betrayed by the Health Board that attempted to get an order to remove P (by force and without notice) from the family home, and haunted by the thought of the lasting damage it would have caused her daughter if an application she was powerless to respond to had succeeded in her absence. She lives with the terror of what might have happened, and the fear that there are still people out there who want to remove her daughter and might try the same thing again. A year later, she says “I’m scared and traumatised by what happened, and the fact it could have been so much worse is something I can’t stop thinking about”.

We’re told that “closed” hearings (i.e. those that exclude a party by order of the judge) are “extraordinarily rare”[5] – but the problem for us in the Open Justice Court of Protection Project is that we keep stumbling across these cases[6] – and since there’s no audit, nobody actually has any idea how many there are. There’s no research on closed hearings – not about their practical consequences for the administration of justice, nor how they affect those involved in, or excluded from, them (or, indeed, those of us who become aware of them as public observers).

Previous commentary on this particular case has focussed on the use of the inherent jurisdiction[7] and injunctions[2]. I’ve not seen any public discussion about the decision to exclude the mother from participation in proceedings about her daughter – and of course nothing about what led up to, and followed the hearing, or its effects upon this family. That’s what I’m going to focus on here[8].

This blog post was written with Zoe’s full participation (via emails and video calls) and she’s read and had the opportunity to comment on it[9]. She is determined to have her story heard, in the hope that other people will not have to suffer anything like this.

I’ve organised this blog chronologically into 5 sections.

1. “Waiting for proceedings to begin” describes what I learnt from Zoe about what was happening to her family before she was formally notified about the ongoing Court of Protection proceedings.

2. “Finding out about the closed hearings” explains what happened between 23rd July 2024, when Zoe and I became aware for the first time that court proceedings were ongoing, and 30th July 2024, the date of the first hearing Zoe was allowed to attend.

3. “The hearings” lists the six (or possibly seven) hearings I’m aware of and describes two of them in detail. In 3.1, I summarise the closed hearing of July 2024, drawing on the published judgment. In 3.2, I describe the only public hearing in this case, which I attended as an observer in November 2024.

4. “Aftermath” offers an account of what Zoe’s experience has been in the year since the November hearing, her ongoing trauma and lack of trust in both the healthcare system and the law (and my own response to this case).

5. “Lessons to be learnt?” reflects on the importance of published judgments to support understanding of where things can go wrong, and considers what could be done to improve practice to avoid parent-blame and systems-generated trauma.

1. Waiting for proceedings to begin

Zoe had been aware since August 2023 that the Health Board was considering a Court of Protection application, and she made contact with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project shortly afterwards. She’d been told about the likelihood of forthcoming proceedings by one of the professionals involved in her daughter’s care, but without any specific details. She expected to be notified and permitted to participate in the usual way. What she didn’t know (or didn’t know for sure) was why an application was being made, what it was for, or (later) that proceedings were actually in progress and that she’d been excluded from them.

By February 2024, she suspected that the court was already involved, although she was not notified until almost six months later. She hadn’t tried to abscond. Instead, she’d sent an email to the professionals involved in her daughter’s care, asking lots of questions about what the Health Board was applying for and why it was necessary, and how it affected her own role as a mother trying to make best interests decisions for her daughter on a daily basis. Her questions were, she says, “ignored”. Professionals may have been evasive, presumably in part because they were already involved in the court proceedings that Zoe was supposed to know nothing about. She says: “Dr Bayley whenever I asked would tell me she had done this process a lot of times – even telling me all of her clients were on Court of Protection and it was nothing for me to worry about. I would get the same response each time I asked. It was obvious they were fed up of me asking about it, and they weren’t being honest with me about it”[10].

Unable to get the information she wanted from the professionals, Zoe contacted the Open Justice Court of Protection Project again towards the end of February 2024, and that was the beginning of frequent correspondence between us over the next few months. This was the time period when (we later learnt from the judgment) the case was before three different judges on several different occasions. It was first before Theis J (I’m not sure when), and then Cohen J in March 2024 (I think both Theis J and Cohen J made case management decisions ‘on the papers’, i.e. without hearings). It was then before Morgan J for three case management hearings, from April 2024 onwards, culminating in the two-day hearing before Morgan J on 16th and 17th July 2024 . All these hearings were in private and without notice to Zoe.

On 29th February 2024, at my suggestion, Zoe sent an email to people she thought might be involved in the court proceedings: Ceredigion County Council Learning Disabilities Team, and two professionals employed by Hywel Dda UHB: her daughter’s psychiatrist, and her treating psychologist. She asked: “Which best interests decisions are you asking the judge to make? Please also confirm if there is a COP case number, judge, court, date and time for the hearing. Have the health authority produced a position statement yet? If so please provide me with a copy of this asap. Has a round table meeting been set yet?” She also said in that same email: “I request that I am made a party to the proceedings”.

Zoe tells me she never received a reply: “Why did all 3 of them ignore the email? Why was it not mentioned that I had actually asked to be made a party to the proceedings as I have been informed by the Open Justice COP Project I had a right to. I am guessing here, but had this email been acknowledged and not buried by all 3 people it was sent to, this would have made my supposed flight risk less believable. I believe this was a deliberate act to make sure neither myself or P could have a voice and be heard. I don’t think it was right or fair to exclude myself and my daughter for almost six months”.

I don’t know why the professionals to whom this email was sent didn’t alert the Health Board lawyers – or, if they did, why the Health Board lawyers didn’t bring it to the attention of the judge. What’s clear is that the judge was not aware of Zoe’s request at the July 2024 hearing and didn’t learn of it until many months later, when Zoe’s legal team submitted it as evidence that she was not now, and never had been, a flight risk. The email shows, conclusively, that far from absconding with her daughter (as the Health Board claimed she would), Zoe was actively seeking involvement in the hearings she suspected were going on without her. “None of them mentioned receiving this email,” she says. “At no point was I a flight risk. I believe this lie was used to deny both myself and P fair hearings and justice”.

During this period, Zoe also tried, and failed, to find a solicitor. How do you find a legal team to represent you when you have no information about the proceedings, and no status in them?

For Zoe (and for her daughter), this was a period of immense distress and anxiety: they had picked up that something was going on in relation to the court but nobody would explain what was happening – and my own efforts to help were misguided insofar as I was minimising Zoe’s concerns about secret proceedings, and providing information and reassurance as if the case was going to be heard in public following normal practice. I’m dismayed to have inadvertently contributed to Zoe’s anguish by outlining for her a set of procedures and practices (based on what normally happens in the Court of Protection) which were never implemented in this case. When we discovered the truth about the closed hearings, the mismatch between what I’d told Zoe to expect, and the reality was shocking to both of us.

Just a couple of weeks before Hywel Dda UHB issued their application (on 28th February 2024), Dr Bayley, the psychologist working with her daughter, told Zoe that the court application was “to look at how [P] is currently being supported”. In response to Zoe’s questions, she and other professionals told Zoe that the Health Board was not seeking Deputyship (something else Zoe feared), and that the application was to ask the judge to make some best interests decisions, including decisions about issues relating to P’s medication and to the restrictions P was subject to at home (e.g. locks on the front door, on windows, and on some cupboards containing medical supplies and caustic substances). It is certainly true that these matters, requiring Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards authorisation, were on the agenda for the court (and they formed part of the final order), but a focus on best interests in relation to “support” and “restrictions” seems rather evasive, given that we now know that the application was for removal of P from the family home.

It wasn’t clear to Zoe (or me) why an application was considered necessary. As Zoe wrote to the psychologist: “I need to clarify what they hope to achieve from taking it to the Court of Protection. In my eyes, as a parent I would always act in [P]’s best interests therefore it shouldn’t be needed?”.

In her emails to me, she described her fear and anxiety about court proceedings and about the ‘welfare’ checks being made on her family. She said: “My local health authority are taking my 18 year old autistic daughter to the court of protection. They have told me they are not applying for deputyship but I believe I am being lied to […] They are now trying to steam roll ahead without being clear to me what their intentions are. They say they are just applying for best interests decisions, but I don’t believe they are being truthful. I don’t know how to deal with situation at all – it seems so wrong. I’m scared I will lose my daughter. Please can you help?”

Like many other parents, Zoe was dismayed by the change of approach since her daughter became an adult: “At the moment I know no one else going through this and it’s just so heart-breaking the authorities can do this, when up till my daughter turned 18 they didn’t care about them[11]”. In response, I provided information about possible avenues for accessing free legal advice (she’s on benefits). I also offered peer support, putting her in touch with another mother who’d been through Court of Protection proceedings for her young adult daughter.

I volunteered that an “observer” (either myself or another member of the core group) could come along and watch, the hearings which we could arrange as soon as she knew the date when the case would be heard. I told her there would be a “Transparency Order” permitting us to report on the hearing, while protecting the identity of P and her family. I explained it would also prohibit her from speaking about the case (in her own name) and since she’d already given me some information, I asked her to send me a copy when she received it. She replied: “I haven’t been served with a transparency order I don’t even know what one is, but as no papers have been filed yet I guess I am allowed to talk freely about what the health authority are trying to do in my daughter’s case”.

In other words, I dealt with Zoe’s questions and concerns as if the case (assuming there would be one) was going to be heard in public in the normal way. I didn’t take sufficiently seriously Zoe’s belief that secret proceedings were already in progress[12] – or that professionals might be “not truthful” about the application before the court.

Meanwhile, Zoe was dealing with “lots of demands for welfare checks” and unannounced visits from social workers, which contributed to her belief that the case was already “in the courts”. Zoe’s daughter, the person supposed to benefit from all of this, was finding the process increasingly stressful. At this point, neither Zoe nor I knew exactly what the Health Board wanted the court to authorise, but Zoe’s greatest fear was that it was to take her daughter away. Nobody ever told her that this was what the application was for: instead, the focus continued to be on medications and, in particular, the authorisation via deprivation of liberty safeguards of restrictions in the home. Here’s a flavour, from Zoe’s emails to me, of what she was experiencing during February and March 2024.

“My daughter is on medication but they [“they” is the daughter’s preferred pronoun] will refuse to take it at times and other times want to take more. Their psychiatrist and psychologist are not really helping them and at times they have made it worse causing meltdowns and upset. Their psychiatrist has said they don’t have capacity to make decisions re medication or medical decisions. Not long after that, Dr Bayley (their psychologist) said to them they didn’t have to take their medication if they didn’t want to, that the psychologist wouldn’t be cross.”

“Now I am even more confused. The psychiatrist is now saying they are not taking it to court for the medical decisions but the restrictions. In that we have medicine, cleaning stuff, sharps locked up, and lock the front door? We live on a main road, and my daughter has run out before into the road. Medicines, sharps and cleaning stuff are locked up because they have self-harmed a lot. Any advice?”

“P had window locks put in in 2021/2022 after jumping from a second-floor window when they were in crisis. We then had cupboard locks put in after they drank cleaning spray, which was suggested to us by social services. Medications were locked up, as P would frequently ask if they could have more medicine when they were feeling unwell and when they were low would want to take the lot. I was always honest and upfront that these restrictions were there to keep P safe, and at no point was I told they were unreasonable”.

In retrospect, I think the professionals may have been using medication issues, and the matter of restrictions in the home, as a ‘decoy’ or distraction from what the hearing was actually (centrally) about. This distraction was successful to the extent that Zoe and I then exchanged a series of emails in which I tried to explain community deprivation of liberty safeguards. But none of this was really to the point, and the ‘decoy’ simply added to Zoe’s sense of being unjustly accused by the implication that she was harming her daughter (e.g. by locking the front door) when in fact she was keeping P safe[13]. (At the final hearing on 6th November 2024, the judge approved all the restrictions Zoe had already put in place as being in P’s best interests.)

In what we now know was the run up to the July hearing, the pressure on Zoe and her family intensified as professionals increasingly sought access to her home to assess her daughter – and concerns about “safeguarding” now spiralled out to include P’s two siblings, both also young adults living at home. (These safeguarding referrals were, Zoe tells me, closed with no further action after the final hearing in November 2024.) Zoe said that these visits – especially those from the psychologist – were unsettling and disruptive for P. She asked for a change of psychologist on 16th February 2024, and she made formal complaints about Dr Bayley first to the Health Board (on 9th March 2024); and then to the Health and Care Professions Council (on 14th June 2024) – with subsequent updated addendums to, or renewals of, both complaints as later evidence became available to Zoe (e.g. from the court bundle). I understand that none of these complaints has been upheld and I am not aware that they’ve led to any sanctions against Dr Bayley, nor to any changes in the Health Board’s policy or practice. Complaints are still outstanding with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).

During the first few months of 2024, Zoe’s priority was her desperate attempt to get better help and support for her daughter during periods of crisis. She identified professionals who she felt helped P (a nurse who was kind and listened to her); she asked for P’s risperidone to be increased in line with recommendations from the crisis team at the hospital because she could see its effectiveness; she chased P’s new mattress that had never turned up.

The large numbers of welfare checks and then unannounced visits following safeguarding referrals did not help her daughter at all, says Zoe. Eventually she tried to stop the visits (“P had asked for no more visits and given how distressed they were I agreed to no more”). She tells me that she still kept management at CTLD (Community Team for Learning Disabilities) updated on how her daughter was via regular emails. Here’s Zoe’s description (from an email to me at the time) of what was happening.

“Yesterday we had a visit from social services as a result of my daughter’s meltdowns and they came in and spoke to my daughter. They said they had to do a welfare check and I let them in because it looked like I had no choice. They got my daughter to agree to an assessment of their needs and what support they could offer. Then left saying they would be in touch. My daughter had a meltdown after they left and was very distressed saying they couldn’t remember what they agreed to and asked me what this assessment was. They couldn’t sleep last night as they were scared they were going to come back and take them and they today won’t open their blinds (as they don’t want anyone to come and take them) and are sat in their tent listening to music and crying.”

Here’s Zoe’s description of another visit:

“We had a pet rabbit, Thumper, who was dying the day before we had the safeguarding team come in to interview P’s siblings. Our last day we had with Thumper was spent being interviewed. The next day we woke up to find Thumper collapsed in his hutch. As P’s siblings were comforting Thumper as he was dying, we had another visit from a social worker. P had broken down, was crying and screaming in the bedroom. The social worker was going on about that we needed to have a back-up plan as I wasn’t going to live forever. This wasn’t the right time to talk about it. P heard, P’s siblings heard, and P’s brother came through to the kitchen, tears in his eyes, and said “no, you don’t get to do this today”. On her way out, the social worker went through and intruded into the lounge where P’s siblings were cuddling and comforting Thumper as he was dying to say goodbye. The cruelty of this was what hurt the most. It was awful and heart-breaking.”

According to Zoe, the psychologist, Dr Bayley, was particularly insensitive to P’s needs:

“All Dr Bayley was interested in doing was constantly talking about respite care – despite us saying we don’t want that. She seems to not understand my daughter. I asked for the psychologist to be replaced because when my daughter was in crisis, she didn’t help them and just pushed respite constantly on my daughter without understanding that made my daughter feel we wanted to send them away – and then they had meltdowns. The hallucinations and voices were getting worse, and Dr Bayley ignored this. That was why I asked for a change of psychologist – a request that was ignored until my complaint to the HCPC when Dr Bayley was asked to step away from my family. I would like to know why the Health Board did not take my concerns seriously. Their failure to act allowed Dr Bayley to cause P and my family untold harm through their actions. Once the visits were stopped with Dr Bayley, P was able to settle again and stopped wanting to die. Dr [X] listened to how they were feeling and increased their medication. Their depression and self-harm decreased. They didn’t have any meltdowns for several months and we hadn’t had to call the crisis team or attend A&E”[14]

Zoe believes that Dr Bayley was “oblivious” to the harm that her visits were causing P and that the court application was a way of punishing Zoe for making a complaint about her: “I asked for a change of psychologist because Dr Bayley’s conduct was such that I could see the impact it was having on P – meltdowns and distress, and I was concerned about the long-term impact on P if this continued. Dr Bayley has never admitted the stress she caused P but has tried to deflect the blame on to me – with a reckless proposal to the court to remove P by force. It was less than two weeks after I filed the first complaint against Dr Bayley in February 2024, that Dr Bayley and the Health Board had managed to convince several judges and other services that I should be kept out of the hearings. They effectively silenced my voice and prevented me from being able to challenge what they said in court. This wasn’t about me being a flight risk. This was about punishing me for daring to complain”.[15]

Eventually, by Spring 2024, P had become happier, started crafting and painting again, and playing board games with the family. P also became able to go out of the house (e.g. shopping), so sometimes the family were not at home when unannounced visits with the nursing team were made. Zoe said: “During these last few months, we have had no contact with the crisis team as we have not needed to call them – and this should be something to be celebrated rather than make us feel we have done something wrong and sending social services round because we haven’t been in contact. I know where the Team are should we need them, but they just simply haven’t been needed because things are now going well”. Zoe says that because they weren’t home for unannounced visits, the Health Board started social services referrals, apparently taking the view that Zoe was refusing services. Another chasm opened up between this family and the professionals.

2. Finding out about the closed hearings

For almost a year, Zoe had lived with the stress and anxiety of Court of Protection proceedings hanging over her, unable to get anyone to explain to her what was going on, fobbed off with evasion, misinformation and bland reassurance. I had done little more than inform her about the usual procedures of the court. But the court was not following its usual procedures.

On 23rd July 2024, court papers were delivered through her letterbox (she’d not answered the door when a delivery had been attempted the previous week), and Zoe learnt that the Health Board had applied to the court to remove her daughter from the home – the one thing she and her daughter feared most. She discovered that there had been multiple hearings from which she’d been excluded and that there were now injunctions against her, compelling her to allow professionals to enter her home and assess her daughter. She emailed me the same day.

This was when I first realised that there had been closed hearings – and also (when Zoe sent me the case number later the same day) that the core team members on the Open Justice Court of Protection Project had actually asked about some of these hearings (listed as “private” in the CourtServe and on the RCJ website) at the time, and had been told they were private (as listed), but not that they were “closed”. I was shocked to discover that I had stumbled, yet again, on a series of closed hearings, and that I had failed to recognise what Zoe was up against. I was utterly dismayed at the impact of these closed hearings on Zoe – and, from what I knew from Zoe, on P, the very person the proceedings were meant to protect.

There is a long series of emails between us over the course of the week after the injunctions were served on Zoe and before the next listed hearing she was invited to attend. I bore witness to Zoe’s distress, anger and sense of utter helplessness in the face of the power of the court.

Closed hearings may sometimes be inevitable (though they weren’t, I think, in this case) – and I want the Court of Protection to think about the appropriate way to inform someone that closed hearings have taken place and that decisions have been made about their family member without their knowledge or involvement. I find it hard to come to terms with the casual cruelty inflicted on Zoe that day. Couldn’t someone from social services have reached out to her to tell her in person what had been happening before (or as soon as) the injunctions were served on her, offering to go through the paperwork, explain it, and answer her questions. She badly needed support – and I was ill-equipped to provide it, nor should I ever have been put in the position where it seemed that I was pretty much the only person Zoe felt able to ask.

Here’s Zoe account (in conversation with me) of what she experienced:

“I remember the day the court papers were pushed through my letterbox. I already had an inkling I was about to be served when I came home from a day out the week before to find a private investigator’s card pushed through my letterbox. I googled it, and found they are used to deliver court papers. I was absolutely terrified. When he next called round, I was in – but I didn’t open the door. I was scared the papers were for them to take P away. The guy pushed the paperwork through the door. I took them upstairs and sat on my bed. I ripped the envelope with tears streaming down my face as I started reading. They were seeking removal of my daughter and they’d never told me. The whole time they’d been lying to me. I just couldn’t read past the place where it was saying they wanted to remove P for assessment – I felt frozen with terror. It took a while before I could read on to the bit where the judge refused the orders they were seeking. And then I just couldn’t stop crying with relief. The hardest part was reading the paperwork and then coming downstairs to be with my daughter and trying to pretend everything was okay. I was breaking down crying over every little thing and struggling to hold it together.

The next day I got the massive bundle, some 100 pages long, and while reading it I was so angry at all the lies told in court, and the fact that I had been denied the right to argue against the lies, to show them for lies. It was hard to accept what had happened. It was hard to realise that I had no rights, no voice – that I couldn’t speak up for my daughter.

It was only when I read through the bundle that the true horror of what the Health Board and Dr Bayley were seeking became known to me. The plan was to use the police to force me from my home while they came in and took my daughter and all her belongings, removing every trace of my daughter while making me stand down the road. My son and other daughter were allowed to remain in the home, but not to interfere. My daughter would be driven away from the home, possibly medicated if they were distressed, and we would not even be told where they were until someone decided to tell us. It was basically legal kidnap of my daughter.”

At the time, although Zoe’s distress was very evident, that wasn’t the focus of the communication between us. We were concerned with getting legal representation, and ensuring that future hearings took place in public. Zoe was also trying to write a witness statement.

In an email on 23rd July 2024, Zoe asked me urgently: “What can be done? I don’t think this should be private given what they have done. They prevented me being able to put my case across. They say in the papers I can make a witness statement but don’t tell me how. It’s all so wrong and yet the judge acknowledged we have a right to have a private life free from interference from government bodies. If the judge had followed what the Health Board wanted, I would have had my daughter removed by force and not been able to do anything. I want it removed from private and heard in public then the health authority can’t get away with this.”

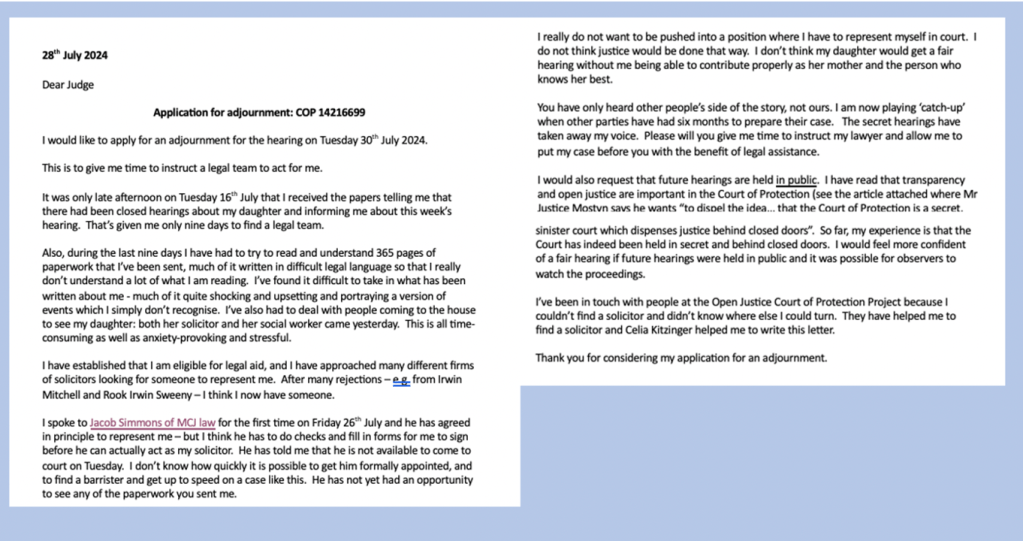

We focused on preparing for the next hearing listed for 30th July 2024. I explained that I didn’t know enough about the case to help her with a witness statement (at that point there was no published judgment and I had only Zoe’s account of what the injunctions against her were, and what had gone on in court[16]). I thought I could most usefully concentrate on helping her find a legal team. As far as I know, none of the lawyers involved in the proceedings offered her any support with finding legal representation[17] (although the judge said at §53 of the published judgment that she wanted to “invite Counsel to provide ZJ with details of specialist practitioners to assist her in obtaining legal advice and representation should she so wish”)[18].

I checked Zoe’s legal aid eligibility and made some suggestions about which solicitors’ firms she might contact, adding (because time was very tight): “If we can’t get your legal team sorted in time, I can help you write a letter asking for an adjournment (i.e. a delay before the next hearing) so that you can get legal representation.” It’s very difficult for lay people to find legal representation at such short notice, and it added to Zoe’s sense of panic and despair. She felt overwhelmed, set up to fail – that it was just her against the lawyers, that she was already at a disadvantage having been “kept in the dark” about what was going on: “I think I have lost already before it even was heard from our side because the minute they chose to have it secret they effectively won, as they have heard only one side”.

By the end of the next day, a couple of firms had said ‘no’ to Zoe and one had pencilled her in for a consultation in a few days’ time. It wasn’t looking good. I emailed her saying: “You can ask for the hearing to be postponed. I will draft some words for you to send to the court to request that. It should be fine to make the request as long as you get it in before Friday 4pm. Get written evidence together that you are actively looking for legal representation (like that letter you forwarded to me from Irwin Mitchell[19]….”. We did eventually find a legal team (thank you to all the lawyers who pointed me in the right direction and to Jacob Simmons, then with MCJ Law and Francesca Gardner of 39 Essex Chambers) – but it was too late for representation at the next listed hearing on 30th July. The hearing took place and Zoe was able to speak in court, and to ask to be joined as a party and for all the substantive business to be adjourned until she had representation – and fortunately, the judge permitted the adjournment Zoe requested.

During this adjournment period, Zoe was worried about “doing something wrong”, which she feared would add to the risk of having her daughter taken away from her, while not really being sure what she was and wasn’t allowed to do. She strikes me as a very law-abiding person. Unlike members of other families who’ve contacted the Project, she has never attempted to share court documents, she’s been cautious about what she tells me, and she was anxious to follow to the letter the injunction served upon her (which I’ve never seen). After the July 2024 hearing, Zoe complied with all requests for access from professionals (in obedience to the court injunction) even when she thought them harmful to her daughter. Here’s a sample from our correspondence on 24th July 2024.

Zoe: My daughter’s solicitors have just emailed me and they are coming on Friday morning. I have a court order that orders me to let them in. So they will be meeting my daughter. My daughter doesn’t know what is happening and it’s very likely that once they are told they will struggle and possibly shutdown.

Celia: Can you help your daughter to understand some of what is happening and that [P’s representative] is there to represent her views? [The representative] will want to know your daughter’s wishes and feelings. She will ask to spend time alone with P talking about what P wants to happen. If you can find ways of supporting P so she doesn’t “struggle and shut down” but can tell [the representative] what she wants, that would be wonderful.

Zoe: I am not allowed to as they will class that as me interfering.

I didn’t really know how to respond to that: could it be seen as “interfering”, and by whom? I couldn’t imagine an injunction that would prevent Zoe from acting as I’d suggested – but then I hadn’t seen the injunction, and I assume it’s a “court document” I’m not entitled to read without the permission of the judge. I didn’t want to put Zoe under any pressure by leading her to believe I wanted her to send it to me.

I now know that the judge (in July 2024) had accepted the psychologist’s (Dr Bayley’s) evidence, that Zoe exerted “undue influence” over P – so maybe the injunction did prevent her from saying anything about the case to her daughter. Claims of “coercive control” and “undue influence” against Zoe weren’t something I knew about at the time, and nothing I’d seen or heard in my interactions with Zoe before or since has led me to think that might be the case. From my (non-professional) perspective, she seems to be a good and caring mother – against the odds, supporting her daughter through multiple crises in the extraordinarily stressful context created by the court proceedings. By the end of the proceedings, that also seemed to be the view of the court. The court-appointed independent expert, Dr Layton, was clear that he had not identified any evidence of undue influence, controlling behaviour or abuse. But that was all in the future.

3. The hearings

I’m aware of six (or maybe seven) hearings in this case: there may have been more. There are only two that I can write much about: the “closed” hearing with the published judgment (16th – 17th July 2024) and the final “public” hearing (6th November 2024) which I observed and which does not have a published judgment, although both Zoe and I requested one from the judge.

Here’s a list of the hearings I know about:

April – June 2024 I don’t know anything about what took place at the first two or three closed hearings before Morgan J. There is no public record of them. I assume they were case management and pre-trial hearings, and that they would have involved matters such as appointing a litigation friend, and deciding on what evidence needed to be before the court.

16th-17th July 2024 The information I have about what happened in the last closed hearing, on 16th and 17th July 2024, comes from the published judgment (Hywel Dda University Health Board v P & Anor [2024] EWCOP 70 (T3))[20]. Zoe has more information than I do because the legal team she was subsequently able to appoint made a successful application for the transcript of this hearing (which includes the cross-examination of P’s psychologist, Dr Amanda Bayley) – but my request to the judge for disclosure of this transcript to me was not granted.

30th July 2024 This hearing was not “closed”: Zoe attended it (and so did I). However, it was listed as “private”, which means that although I was able to attend as an observer with the judge’s permission, I can’t report on anything said in the hearing. Some of the information communicated in this hearing was reported in the introductory summary and/or in the position statements at the only public hearing in the case (on 6th November 2024), and that I can report on. On that basis I can say that, as Zoe had requested[21], the judge joined Zoe as a party, and adjourned consideration of substantive issues to allow Zoe the opportunity to consult with her soon-to-be-appointed solicitor and to be represented in court. The judge also accepted that Zoe had provided written confirmation that she would cooperate with the requirements for assessing P, and on that basis discharged the injunctions against Zoe. She said she would further consider Zoe’s request for future hearings to be held in public – but in fact only the final hearing was “public”.

14th August 2024 This was another “private” hearing – which I again attended with the permission of the judge, but the same reporting restrictions apply as with the hearing on 30th July 2024. I’m not sure whether it was at this hearing, or at the hearing two weeks earlier (30th July 2024), that the judge approved the appointment of an independent expert – consultant psychiatrist Dr Mike Layton (his appointment was discussed at both). He specialises in complex neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric conditions and has given evidence in other reported Court of Protection cases, as listed on his webpage. He is named in the (public) approved order of 6th November 2024 and his report was discussed in the hearing of the same date. I can also report – because it’s in the position statement provided at the public hearing, that “as at the date of [this] hearing [Zoe] raised significant concerns as to the conduct of the Health Board, and specifically the ex parte nature of the Health Board’s initial application”. I heard her raise these concerns in court – politely, articulately, and with unwavering sincerity. Her sense of having been deeply wronged was palpable.

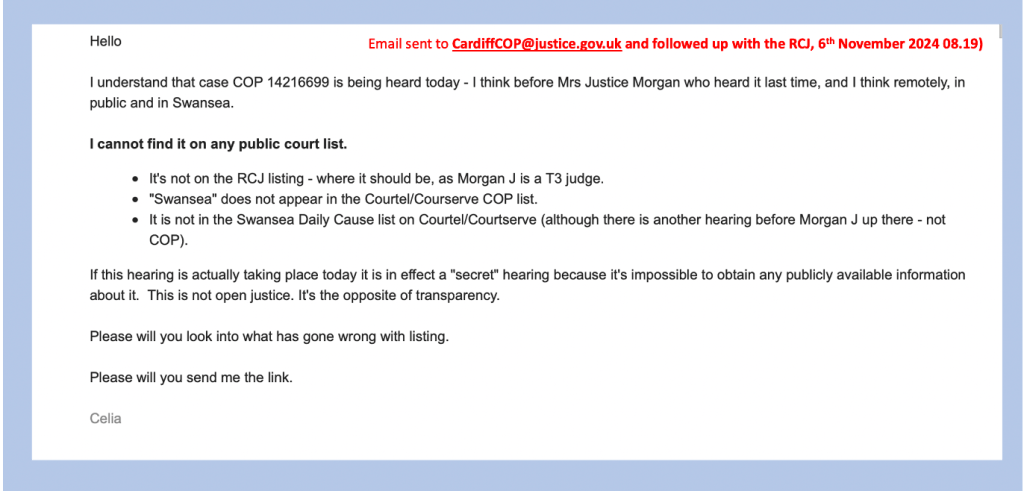

6th November 2024 This was supposed to be a public hearing (and I was sent a standard Transparency Order), but it didn’t appear on either Courtel/Courtserve or on the Royal Courts of Justice Daily Cause list. If I hadn’t already known about it, I wouldn’t have been able to observe – and of course there were no other observers present[22]. The judge also approved release of the parties’ position statements for this hearing. Since this was a “final” hearing, I asked the judge to publish a judgment. She agreed to publish the judgment from the closed hearing, but only later realised (following my correspondence with her) that I was also requesting publication of a judgment from the 6th November 2024 (final) hearing. And that she declined. Zoe subsequently made the same request for publication of the judgment from the final hearing and told me: “the judge questioned why I was asking so long after the hearing finished and I pleaded I needed the truth out there, not the version that made the Health Board look like they were right – it was refused”.

In the next two subsections I report on the two hearings about which there is public information: 3.1 covers the closed hearing with the published judgment; 3.2 covers the only public hearing in the case.

3.1 “A false narrative”: The closed hearing of 16-17th July 2024 (with a published judgment)

At the hearing on 16th and 17th July 2024, the judge refused the Health Board’s application for authorisation of forced removal of Zoe’s daughter from her home, without notice to the family. Instead, she made (under the inherent jurisdiction) “the minimum order required to address potential harm to P” (§49) which was an order that “enables entry and access to P for assessment purposes at the home and prevention of her removal from that address by her mother or by others on the instruction of her mother” (§51).

The published judgment from this closed hearing (Hywel Dda University Health Board v P & Anor [2024] EWCOP 70 (T3)) is dated 22 July 2024 on its face, but in fact it wasn’t published until the very end of November 2024, after the proceedings were over. Despite having requested a copy from the judge, I did not have access to the judgment until November, so I was trying to support Zoe after the July 2024 hearing while still not really understanding what had actually gone on. (Although Zoe had been sent the court bundle and the unpublished version of the judgment, she very properly did not share court documents with me.) Eventually, months after the end of the July hearing, I was able to see what the court had decided and the reasoning behind the judge’s decision.

Here’s a summary, based on the published judgment.

The applicant Health Board (Hywel Dda UHB, represented by their in-house lawyer, Rachel Anthony) said there was an urgent need for P to be properly assessed so that appropriate support services (and possibly continuing health care funding) could be put in place. Zoe was said to be obstructing access to P by refusing to allow professionals into the family home. So, they asked for an injunction – either under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 or under the inherent jurisdiction – that would have the effect of removing P from the family home immediately, and without notice to the family, for the purposes of assessment elsewhere (§7).

Neither the litigation friend appointed to act for P (the Independent Mental Capacity Advocate, Beth Owen, represented by Ian Brownhill of 39 Essex Chambers) nor the local authority (Ceredigion County Council, represented by Hannah Meredith-Jones of 30 Park Place) supported the Health Board’s application.

The local authority said that P’s mother “should be given notice before any order is made against her” (§6) saying that they wanted to work openly and honestly with the family. Reluctantly, they accepted that the July hearing could go ahead without Zoe’s participation, but supported the litigation friend’s position that “before there is any prospect of a move of P from the family home, [Zoe] should have the opportunity to make submissions” (§6). The litigation friend also “strongly opposes any order which has the effect of removing P from her home without evidence of her wishes and feelings” (§8).

Two key professionals involved in P’s care gave oral evidence during this hearing: Dr Amanda Bayley, P’s treating psychologist, and Ms Lisa Hewson, a social worker from the adult learning disability team. Their evidence was very different – both about P’s mental capacity (though neither had conducted formal testing) and about P’s wishes and home circumstances (§10-13 of the judgment).

It was on Dr Bayley’s evidence that the Health Board primarily relied in making their submissions that P should be removed from the family home as soon as possible, and without notice. The judge acknowledged that “Dr Bayley’s evidence should be treated with caution considering that ZJ had made formal complaints about Dr Bayley’s conduct” (§52(vi)) but did accept parts of that evidence in her judgment.

A disturbing part of Dr Bayley’s evidence was her claim that Zoe was exerting “undue influence” over her daughter – a claim accepted by the judge (§37).

One aspect of this alleged “undue influence” was, according to Dr Bayley, Zoe denying her daughter the opportunity of living other than at home with her. Dr Bayley painted a picture of P as someone who wanted to live away from the family home – and Zoe was said to be opposing her daughter on this, and preventing P from having access to professionals who might facilitate a move elsewhere. By contrast, the evidence from Ms Hewson was that “she did not experience P expressing a wish to live elsewhere” (§12). The judge seems to have preferred Dr Bayley’s evidence. Here’s how the judge puts it:

“I was interested […] to hear that P had at one point been able to express to Dr Bayley a wish to leave the family home and live elsewhere. So limited however, is P’s life experience, that her only concept of what elsewhere might be, was ‘hospital’ and so that is where she indicated she would like to go. This it emerged was because other than a short hospital stay for an infection, P had no experience or concept of not living at home with her mother. It did appear however to indicate that, at a point during Dr Bayley’s engagement with P, P whilst lacking the vocabulary and life experience to give it a name was able to engage in, and on Dr Bayley’s evidence to raise herself, the possibility of a different way of living. […]. Dr Bayley was also of the view that once a view had seemed to be articulated by P in which she expressed a wish to live otherwise than her present arrangements, that this was swiftly followed by rejection by the family of professionals and a shutting down of access to P.” (§11)

Dr Bayley’s witness statement also “described obstruction by [Zoe] to services and assessments for P and to the putting into effect of decisions. In her oral evidence Dr Bayley amplified this and was explicit that she had come to the view that a wish P had been able to articulate to her of living elsewhere and in a different way had been affected by ZJ and that rejection of professionals and access to P thereafter was a result”.

The judge said she “took particular note of the lack of response [from Zoe] to clinicians during periods of difficulty: of refusal to allow community learning disability nurses entry to the family home; declining assistance and visits …” (§37). She found “reason to believe at this stage that P is subject to coercion control or constraint” (§38).

The outcome of the hearing was that the judge authorised assessments of P in relation to her capacity to conduct proceedings, and to make decisions about residence, care, support, medication and property and affairs. Additionally, in relation to care, support and treatment, she authorised a medication review, a review of treatment needs and an assessment of P’s care and support needs (§44). These assessments were to be carried out at home. The judge said: “I will not at this hearing sanction the removal of P from her home address when I know nothing of her wishes and feelings; when I am making an order exceptionally ex parte and when I recognise the effect that the orders I make today will have on the rights, life and emotions of P and her family. Rather I will make the minimum order required to address the potential harm to P” (§49).

Because she did not think that Zoe would willingly or voluntarily allow the assessors into her home, the judge also made an injunction against Zoe, saying that she must permit access. “The thrust of the evidence I have heard and read at this hearing is strongly suggestive of ZJ controlling access to and ‘gatekeeping’ P and absent the injunctive relief is more likely than not in my judgment to resist or interfere with the intended assessments” (§49).

Finally, although the judge had heard the case so far ‘without notice’ to Zoe because of the “real risk … of ZJ absconding with P if she has notice” (§28), she made a declaration that Zoe should be notified of the hearings going forward, having decided that Zoe’s flight risk was small. This was partly because of Zoe’s limited resources (e.g. she has no car), and partly because she did not accept that fleeing from an abusive relationship with small children in the past should be treated as evidence that Zoe was likely to flee from the court with her now-adult offspring in order to evade its orders. The judge decided that Zoe would be given notice of further hearings.

It’s not true, Zoe told me, that P wants to leave the family home and live differently. When P asked to go to hospital it wasn’t, Zoe tells me, because that was the only way they knew to say they want to live away from their family. It was because they were really struggling (“hallucinating, seeing blood, dead bodies, and people hanged’) and they wanted to go to hospital to feel safe and to get better. Her daughter “never asked for respite or to live away from home like the Health Board said”. The offers of “respite” care actually frightened P says Zoe, and the idea of being taken away from home (other than to hospital in a crisis) was something P found very upsetting.

This was later confirmed by the independent expert appointed by the court to visit and assess P: Dr Layton said that “even hypothetical discussions” about the possibility of moving to live somewhere else could be “a significant trigger at the moment” and might “destabilise [P]”[23]. This was so serious a risk that he was not able to complete a proposed assessment of P’s capacity to make decisions about residence.

The judgment is cautious about what is communicated on the topic of Zoe and her life experience – but Zoe discovered from the bundle that the Health Board had put before the court a large amount of private and confidential information about her, some of it incorrect (e.g. claims about her mental health) and of dubious relevance to the case. She’s horrified that her experience of domestic violence, and other traumatic aspects of her past – not all of which can be reported – were used in effect to “re-victimise” her in the evidence presented to the court. The Health Board was “throwing out my whole life out there for others to judge and this should not have happened”. It felt to her as though she was on trial – as though she was being portrayed as “a mentally ill, unfit mother”.

3.2 Retelling the story: The final hearing (6th November 2024)

After a short “private” part to the hearing, the judge asked counsel for the local authority (Rachel Harrington) for a brief opening summary. Counsel gave an abbreviated history of the case, and updates since the July hearing – including Zoe’s full cooperation with the assessments as required of her in the family home.

“There have been no concerns raised about [Zoe’s] cooperation or involvement with the assessments. There has been success in undertaking the initial assessments from SaLT, the medications review, assessment of cognitive and adaptive function, and the CHC checklist (P did not meet the criteria for CHC funding). Dr Layton, the expert appointed to consider capacity, has provided a 105-page interim report. It’s ‘interim’ because of his concern that the proceedings risked destabilising P, who was not responding well to the myriad of professionals coming in to assess her – a concern shared by [Zoe] and the speech and language therapist”.

The position statement filed for Zoe (by Francesca Gardner) also records this: “prior to completion of his report (and prior to completion of his assessment), Dr Layton wrote to the parties, expressing concern as to the impact on P of ongoing assessments and asked the parties to consider the purpose of ongoing assessments […] Dr Layton was clear that he had not identified any evidence of undue influence, controlling behaviour, or abuse from [Zoe] … [Zoe] was and is relieved that Dr Layton identified the significant distress and ‘pressure’ that the repeated assessments and these proceedings are causing”.

The judge asked: “So what is the position of the parties today?”. It turned out that none of the parties wanted the case to proceed. Assessments had been carried out to the extent compatible with P’s best interests. P had been found (at least on an interim basis) to lack capacity in relevant areas, meaning that the court had jurisdiction under the Mental Capacity Act to authorise DOLS, including the “safety plan” agreed between the parties (such as locking windows and doors). It had been determined that P is not entitled to continuing healthcare – so it’s the local authority that’s responsible for commissioning services. With the exception of the local authority (which wanted a six-month authorisation), the parties had agreed on a standard one-year DOLS authorisation. The litigation friend (now Louise Williams) was to be appointed as P’s Rule 1.2 representative to be involved in scrutinising care plans.

The judge then drew attention to the notable difference between the situation today and at the July hearing. “There is no suggestion that P should be anywhere other than in the family home? Remaining at home is in her best interests?”. There was no dissent. The evidence about P’s home environment now seemed uniformly positive. The litigation friend for P said that P was “well-cared for and happy”. Counsel for Zoe spelt it out in more detail: “P lives in a loving home with her family, and is well cared for. This is demonstrated by the fact that the Health Board now invites the court to make an order that it is in P’s best interests to continue to reside at home, and to receive care from their mother. This is a world apart from the picture that was painted to the court by Dr Bayley in July 2024. The litigation friend for P has raised no concerns following her visits to the home: ‘Coming away from the visit with P, I must note the very different situation I observed in the family home to that portrayed in the evidence I have read as part of the application’” (Position statement from counsel for Zoe).

The judge then turned to the matter of DOLS authorisation, beginning with Zoe’s counsel (Francesca Gardner) with whom the interaction segued to address broader concerns about the case – in particular, the ’without notice’ proceedings kept secret from Zoe.

Judge: Ms Gardner – there are a number of striking features of the history of this case. The step I was invited – but refused – to take, to remove P from her home – is one that even the mention of a change of home appears to be the thing that causes her the single most anxiety and distress.[…] Alongside the fact that, contrary to what the Health Board evidence suggested when they asked to remove P from her- from their home, there has been no aspect of anything that’s been asked that [Zoe] has not cooperated with since then.

Counsel for Zoe: That’s right, My Lady. We are acutely conscious that we have on a number of occasions raised concerns about the way the proceedings were brought. That provides an important context as to why there are these ongoing anxieties and upset in the family unit. It is still unclear to [Zoe] why you were invited to take the step you were. And but for your extremely careful scrutiny of the evidence – and that of the litigation friend – this could all have been very different for P. In my client’s words, it has “terrified” her, what professionals could do. It has had a lasting impact. She welcomes professional support to open up P’s world, but this must be seen in the context of what’s happened. The door to the family home has been opened. There is significant access to P. No concerns have been raised when professionals have been in and out of the family home. There are positive reports about the home, the family relationships and mother-daughter attachment, P’s love of crafting, and her need to have quiet time alone in her bedroom. This could all have been achieved with [Zoe] being on full notice of this application – and the fact that it was done without notice has caused damage. Also, the opportunity to challenge Dr Bayley’s evidence has now been lost. My client is distressed. There needs to be a period of calm. The unanimous impression is that P is struggling with the number of ongoing assessments …. There needs to be some breathing space, to allow relationships to be built away from the scrutiny of the court. I respectfully urge you to be cautious if you are minded to conclude these proceedings for only six months: there is very little difference between court proceedings continuing and a DOLS in six months. We invite you to authorise for 12 months. If it were not in court already, this matter wouldn’t be before the court – there isn’t a dispute for the court to determine. We also ask you to discharge the Health Board as a party to the proceedings. The local authority will assume the role of applicant, and it would be for them to bring the case back to court if that is needed. The professionals unanimously say that the current arrangements should continue – which is compelling, given where the case was six months ago.

Judge: The first notice your client had of the proceedings … was when she was provided with the judgment…. My judgment was provided to the parties on 22nd July 2024 and she appeared fairly shortly thereafter in front of me. So to the extent that I look at cooperation from her side, I have as far as I can see an unbroken period of unstinting cooperation in all that has been asked of her from those wishing to see her daughter. She has expressed her frustration, dissatisfaction and dismay at the way the proceedings were brought, but has nevertheless worked alongside that for P’s good. I would be interested in knowing whether, on your instruction, your client trusts those who would be providing services and input without oversight of this court.

Counsel for Zoe: Her position is that Dr Bayley is no longer involved in this case. She is content to work with the local authority. The issue that arises with Dr Bayley – the main witness the Health Board relied on to seek the order removing P from her home – was not supported by the local authority.

Judge: You have invited the Health Board to clarify why they took the actions they did and you’ve asked whether the Health Board is going to apologise to the family, and reflect on its practices going forward.

Counsel for Zoe: The Health Board has not responded to that until this morning and says that the proposed form of words is yet to be decided. There has been no contact with [Zoe] or any acknowledgement that it ought to reflect on this. That is extremely disappointing.

Judge: (picks up on the issue of why she heard the case in July without notice to Zoe, as sought by the Health Board on the basis of Dr Bayley’s evidence; and responds to counsel’s suggestion – in the position statement – that she might say something about the exceptional nature of hearings without notice. This is not directly responsive to what Zoe’s counsel has said orally. If what follows is obscure to the reader, I think this is deliberate – she’s alluding to “private” information known to the parties but not for publication). I understand your client’s disappointment at the response of the Health Board to the invitation to offer an apology for the orders contended for and for how the case was brought. There will be some material not suitable for discussion at this part of the hearing, but it may be that that aspect which has disappointed your client today is pursued in some other quarter[24]. It is an aspect of the case that does trouble me because of all the reasons set out in my judgment, on the basis of the evidence before me at the time. It was an application that was acceded to by me, albeit that the orders contended for were not ones that I found should be made. Having acceded to that application for the reasons set out, and having regard to the relevant case law, I read with (pause) interest that your client (pause) invites a comment from me as to the exceptional nature of ‘without notice’ applications and the importance of transparency. Having, in the run up to this hearing, reconsidered the judgment that I delivered as to the exceptional nature of ‘without notice’ proceedings, they are proceedings that remain exceptional, and I don’t, for my part, regard it as necessary to say more than that. Nothing about this case leads me to think it appropriate that ‘without notice’ proceedings are any less exceptional than they ever were.

Counsel for Zoe: My client understands why you made the decision to hear the case without notice – the problem was the way the application was made. She was aware that court proceedings were in contemplation and contacted the Health Board and asked them, and they told her nothing. She contacted Professor Kitzinger who has been supporting her throughout these proceedings. It is the conduct of the Health Board that has caused concern, not your decision to hear this case without notice.

Judge: Yes. On the basis that you and your client will have a better picture of what informed the Health Board’s thinking when material has been disclosed to you, I will leave it to you to pursue it further – but the arena for pursuing it will be outside the court. I want to make sure your client understands that. Before concluding the proceedings (as appears to be the consensus), since proceedings are likely to do far more harm than any use they are likely to be for the family […] (choosing words with great care) I am sure that it is not lost on the Health Board that applications without notice are brought rarely and for good reason. I am sure also that it is not lost on this Health Board that if it finds itself considering doing so again, it may want to have very specialist advice from somebody who is a very senior practitioner in what is, on one view, a very niche area of law, before committing itself to such a course. I have no doubt that those lessons will have been absorbed. I also don’t lose sight of the fact it so happens P’s mother has responded to the judgments that I reached in a way that has been wholly positive and entirely cooperative, and that the Health Board has to balance in its mind that there might have been a different outcome. I am entirely satisfied that not only is there no reason for these proceedings to continue, but there is every prospect that more harm than any possible good will come out of doing so. In reaching that conclusion, I am particularly struck by the following aspects of the case. [Zoe], who was thought to be somebody who posed not only a flight risk but a risk of no cooperation at all for her daughter’s well-being absent the orders I was being invited to make, first learned of the orders from my judgment. Since then, she has cooperated entirely with everything asked of her. There have been no complaints about her behaviour, or the way she provides care to her daughter, or the way she cooperates with those professionals who’ve been in to assess her – and there have been many. I was very struck by Dr Layton’s observation that continuing and multiple assessment was causing active damage to P. The Health Board that was asking me to approve P’s removal without notice are now saying that she should stay there. I had wondered, although it was clear to me that [Zoe] had cooperated fully, whether she would feel that those providing services would need the oversight of the court for her to feel confident. She does not. The relationship with the local authority and their staff members has not been fraught with the same difficulties as those that attended the Health Board – and that largely related to a professional who is no longer involved. I have come to the conclusion that since the care and support that can be provided does not need the oversight of the court, and since the involvement of the court is such as actively to be unhelpful, it’s appropriate to draw these matters to a close today. I will provide that in the event that the 12-month authorisation is returned to court, that will be by the local authority. I am invited to discharge the Health Board as a party and I incline towards discharging them before making the rest of the order, because I think that is likely to assist with diminishing the anxiety of the family. In the event of any further application by any public body in respect of this family, it is to be made in the first instance to me, if available, or in the absence of that, to a judge of the family division. Only in the most exceptional of circumstances can I imagine that it would be appropriate for any application to be made without notice in this case again. I would expect that if an application were made to me, it would be on notice to [Zoe].”

I have a copy of the order from this hearing. It declares that P lacks capacity to decide as to care and support for neuro-developmental and emotional and behavioural needs and that “P is to reside and receive care at the family home”, subject to restrictions that amount to a deprivation of liberty including locked windows, doors and cupboards, and supervision in the home and in the community. The next DOLS application from the LA was due 12 months later, no later than 4pm on 5th November 2025 and “shall be conducted as a consideration of the papers unless any party requests an oral hearing or the Court decides that an oral hearing is required”. Any future applications must be made in the first instance to the Honourable Mrs Justice Morgan DBE.

And that was that, for the next year. At time of publishing this blog post, that DOLS application has been submitted and Zoe does not yet know the outcome.

4. Aftermath

This secret Court of Protection case and the role of the Health Board in Zoe’s family life has had a lasting negative impact. Zoe has lost all confidence in the health care professionals who were supposed to be supporting her daughter but who went behind her back to try to get her daughter taken away – and despite the outcome of the proceedings Zoe says “I find myself having very little trust in a legal system that allowed this injustice to go on for so long”.

She refers also to “guilt” and “trauma”. “Guilt is something I will carry for the rest of my life. Trauma too. This whole experience has changed me completely. It’s changed all of us.” The “guilt” comes from not having been able to protect her daughter from danger and from obeying court orders even when she knew that they were not in the best interests of her daughter: “I was having to put what the Health Board wanted above my daughter’s needs, under the threat of having P removed if I didn’t allow this to happen”. The “trauma” comes from the combined power of the Health Board and the Court of Protection and the helplessness she felt caught up in a system that harmed her daughter. Zoe complied with the injunctions served on her following the July judgment and she continued to comply (for fear of losing her daughter) with requests for access after the injunctions were lifted. They required her to allow professionals access to her daughter. She then found herself having to juggle very large numbers of appointments requested by professionals wanting access – sometimes conflicting appointments on the same day, and up to four appointments in a single week on one occasion – all of which she could see caused P increasing distress.

“Even though the Health Board said they would work with P and what P wanted, they didn’t. As you will see from letters with appointments, P was bombarded with appointments so close together. They pushed P to the point where they became distressed, sobbing, going non-verbal again and at serious risk of having a breakdown. This only stopped and appointments were ended when Dr Layton saw the effect this was having on P and contacted my daughter’s team, and said he was concerned it was impacting on my daughter’s mental health.” (Zoe)

Thing are better now. Zoe has good relationships (as she did before) with some professionals, and speaks warmly of Lisa Hewson (“P is teaching her to cross stitch at the moment”). She’s grateful to her daughter’s Litigation Friend, Beth Owen, who “made sure P’s voice was heard”. And P’s mental health has continued to improve.

But today, more than a year after the end of proceedings, Zoe is still clearly traumatised. She’s distraught about what has been done to her family and on high alert for potential danger to her daughter in the future. She goes over and over what happened, reliving it, overwhelmed with anxiety and dread. She absolutely doesn’t trust the Health Board not to try to remove her daughter again, and the annual DOLS procedure – which we hope will be approved on the papers – caused her acute distress at the possibility of another court hearing. Her view is that the Health Board doesn’t think they’ve done anything wrong – which means they might act that way again in the future.