By Claire Martin, 9th July 2024

At the centre of this case is Mrs G who has come to the attention of the court because carers have alleged that her daughter is abusing her. Mrs G is said to complain to carers about her daughter’s behaviour, and then to retract these statements later. Her capacity to decide about contact with her daughter (amongst other things) is now in question. Mrs G’s daughter denies, vehemently, all of the allegations, including a report that she threw food over her mother.

Mrs G was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, which is now also in question. A jointly-instructed independent expert has informed the court that his assessment suggests this diagnosis is incorrect and that Mrs G retains capacity to litigate and decide her care and support. The Local Authority disputes the independent expert’s assessment on these matters.

Mrs G wants to instruct her own legal representative. Even if Mrs G has capacity to do this, there is concern (from the Local Authority) about whether she can she do this freely without undue influence from her family. Her daughter holds Lasting Power of Attorney (both for Property & Finance, and for Health & Welfare); the Local Authority made an application for this to be suspended. along with many issues of capacity for Mrs G.

We observed a hearing for this unusual case, COP 14187074 (which we have blogged before), before Mrs Justice Arbuthnot (a Tier 3 judge), sitting in Norwich County Court, on Thursday 6 June 2024.

At the time of the previous hearing on 17th January 2024, two different legal teams had turned up in court to represent Mrs G and the judge decided that her representation should be via the Official Solicitor since there is reason to believe that she lacks capacity to conduct proceedings in a case concerning whether she is subject to control by her daughter.

This post covers (1) Accessing the hearing; (2) Who’s who in the hearing; (3) Background to the case; (4) Issues for the court at this hearing; (5) What happened at the hearing; (6) Mrs G’s daughter, the Inherent Jurisdiction and undertakings; and finally, (7) Reflections.

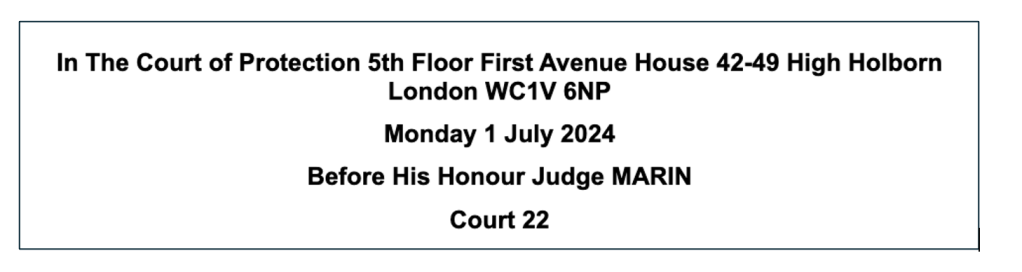

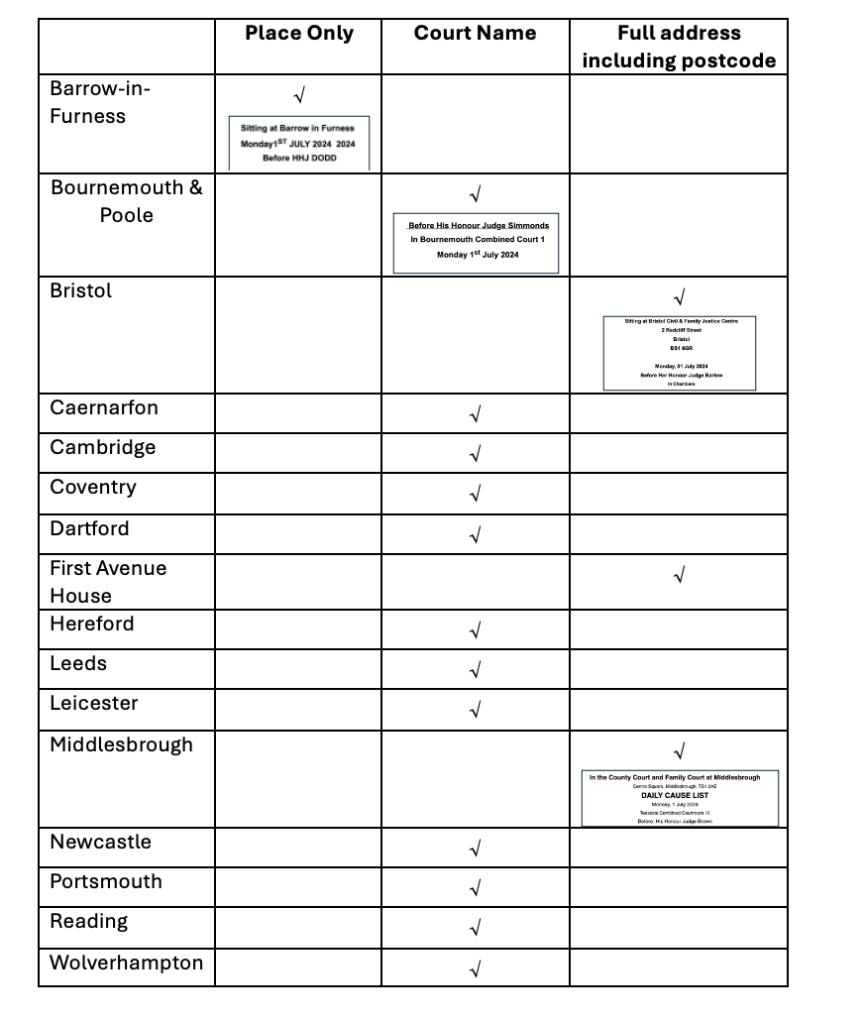

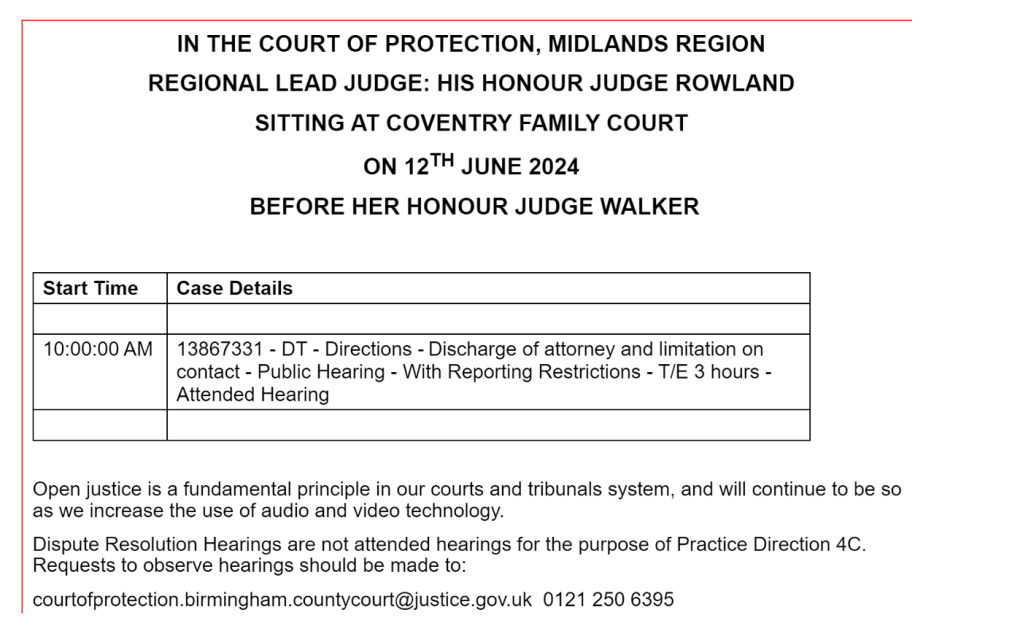

1. Accessing the hearing

When I joined the hearing – which was an in-person hearing – which I and another observer were watching remotely – we were the only people in attendance on the remote link.

It was very hard to follow what was going on for two reasons: there was only one camera in the court and the courtroom appeared to only have one microphone (the judge, at the bench, had her own). In the morning session, we could only see the judge on camera. Others spoke and it wasn’t always clear who was speaking. After emailing the court clerk, the camera was turned to face the courtroom in the afternoon session. This meant we could see all those present in court, but not the judge, whose disembodied voice we heard well because she had her own microphone. This did make it somewhat easier to follow proceedings, though we witnessed the court usher moving the one sole microphone between people as they spoke, causing some difficulty at times to shuffle it between them all. At times, he forgot to move it, meaning we hardly heard some of what was said. So, overall, the sound access to this hearing was patchy. We have done our best to piece together what happened! We have had the benefit of the Position Statement for the Official Solicitor (kindly shared with us by counsel, Malcolm Chisholm) which has helped us greatly to understand the facts of the history of the case.

2. Who’s who in the hearing?

At first we were unsure who was representing Mrs G. As noted, we couldn’t see the courtroom and when the hearing got underway at 11.49am, it was exceptionally hard to hear the voice of the person who turned out to be Oliver Lewis, counsel for the Local Authority. We don’t know whether the case was introduced, but we heard him mention the Transparency Order [TO] (which we hadn’t received at this point) and the judge said that ‘it applies’. We did receive the TO at 12.09 from the court clerk and checked to see what it covered, and to ensure that we are not in breach of any of the injunctions in this blog.

As is usual, we cannot name or publish anything that is likely to identify Mrs G, or members of her family. We are not restricted from naming the Local Authority, however, which is Norfolk County Council.

Mrs G was now represented by her Litigation Friend the Official Solicitor [OS], and Malcolm Chisholm was counsel for the OS.

The only other person formally able to address the judge was Mrs G’s daughter, who was representing herself.

We heard all three speak during the morning session, though could not see them.

Mrs G put her hand up at one point and the judge invited her to speak. More of that later. When we rejoined for the afternoon session, we could see that there were other people in the courtroom too, including Mrs G herself, and others sitting beside her, who turned out to be her ex-husband and her daughter’s partner. We think there were also solicitors for the Local Authority and for the OS.

3. Background to the hearing

We were very thankful for the Position Statement from the Official Solicitor to help us understand the background to this case.

Mrs G is a woman in her 70s. She lives in her own home with a live-in carer, though Mrs G asserts that she can be more independent. In 2021 Mrs G was diagnosed by the local memory clinic with Alzheimer’s dementia. Her daughter holds Lasting Powers of Attorney for both Property & Affairs and for Health & Welfare.

Mrs G came to the attention of the Local Authority in February 2023 when she spent a period as an inpatient period for a chest infection. Health care professionals raised concerns with the local authority about Mrs G’s daughter (we are not sure what exactly the concerns were). There was some dispute about Mrs G’s needs on discharge from hospital, and this has led to the application to the Court of Protection.

The council asserts that Mrs G needs live-in care to support with eating, prompting for personal hygiene, cleaning and ‘accessing the community’. The council also alleges that Mrs G’s daughter has ‘overridden her autonomy’ and that has assaulted her. Mrs G’s daughter denies all accusations and asserts that her mother has capacity to make all her own decisions. The council has applied to restrict contact between Mrs G and her daughter, as well as the daughter’s ex-husband and current partner.

Importantly, there have been two more recent (2024) psychiatric assessments of Mrs G. One was done by a previous treating clinician (who we think was instructed by Mrs G or her daughter) who assessed Mrs G as having ‘mild cognitive impairment’ and stated:“I believe she has capacity to decide her care needs, where she should live and decide who should have financial control over her assets. In addition, with support, she has at present legal capacity”. The other was by Dr Barker, an independent expert psychiatrist, jointly instructed by the legal teams in this case. He also reached the conclusion that Mrs G had a “…relatively mild, memory impairment, particularly with spontaneous recall, which is common with normal ageing, but not typical of Alzheimer’s disease … [Mrs G’s] cognitive impairment has not yet reached a level at which a diagnosis of dementia would be appropriate, and her cognitive testing has markedly improved since the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease was given in 2021, suggesting this diagnosis is incorrect”.

4. Issues for the court at this hearing

The issues were mainly about deciding how the case was to proceed. There are many substantive issues for the court to decide:

- Litigation capacity

- Capacity [and best interests, if appropriate] for other decisions – including where to live, contact with her family, care and support, appointing (and revoking) an LPA

- Fact-finding regarding allegations of bullying and coercive control levelled at Mrs G’s family, principally her daughter. This is considered under the Inherent Jurisdiction.

- Potential committal proceedings against Mrs G’s daughter – depending on the outcome of the fact-finding – we think (though are unsure) for breaches of the court order in relation to contact with her mother.

5. What happened at the hearing?

Sound was very patchy at the start, except for the judge who was more audible. What was clear was that this hearing is what is called a ‘directions’ hearing – the judge and Oliver Lewis were immediately engaged in considering how many days of court time were going to be set aside to hear evidence about various matters: capacity, fact-finding “and then we go from there” (as the judge put it).

There is a significant amount of paperwork for this case, especially allegations against Mrs G’s family from various professionals involved in her care – the judge referred to ‘some direct, some not direct’ and advised counsel for the Local Authority to ‘choose your best evidence’.

And does Mrs G have litigation capacity? If she does she can instruct her own legal team. Counsel for the OS said: “This is a case where all capacity issues overlap: litigation capacity, care, residence, contact and support, LPA …. [There is] artificiality when we look in silos… you may take a view to deal with all capacity issues at the same time. If I am here for the OS I am advancing a case on a best interests basis, taking into account her wishes and feelings, but I can’t take instructions from her [poor sound quality] …. about her own capacity … The neater way is a one-day litigation capacity hearing and see where we go from there.”

Of course, if Mrs G has litigation capacity, she might prefer to instruct a different legal representative, i.e. someone other than Malcolm Chisholm. This issue, therefore, needs addressing first. Oliver Lewis was very clear on the position of the Local Authority, that – regardless of litigation capacity – they would still submit that Mrs G needs to be protected under the Inherent Jurisdiction, due to what they say is coercive and controlling behaviour from her family. The Local Authority also disputes Dr Barker’s findings, so he will need to be called to be cross-examined.

Counsel for the OS and counsel for the Local Authority took different positions on how to handle the multiple capacity issues in this case. The Local Authority proposed all capacity issues to be dealt with together whereas the Official Solicitor advocated for only litigation capacity to be considered at the next hearing. The Position Statement for the Official Solicitor states that the ‘Official Solicitor is in an invidious if not impossible position, namely acting as litigation friend in the best interests of a protected party who asserts (with the strong backing of an expert witness in two detailed reports) that she has capacity to give instructions on all relevant matters’.

Mrs Justice Arbuthnot wrestled with this during the hearing, describing the dilemma as finding the ‘the least worst option’. Here are the arguments and considerations presented to the judge:

Counsel for the Official Solicitor – on behalf of Mrs G: “…. Litigation first …. rather than all at once. My submission would be just on the matter of litigation capacity, not the others, so that if your determination is that P has litigation capacity, she’s in a position to instruct, so that other capacity issues get resolved on that basis. […] there is a sharp distinction between the two roles [acting for the OS and acting directly for a client with litigation capacity]. So litigation capacity needs dealing with in a separate silo.” [Counsel’s emphasis]

The judge was initially persuaded by this argument: “I think he’s right it should be litigation first”. But counsel for the Local Authority: said “In my submission there are dangers of that approach.” Linking litigation capacity to coercive control, he continued: “There are indications in my submissions that Mrs G lacks capacity to conduct proceedings as well as [other capacity issues]. It would be artificial to separate it out. If we were in the King’s Bench division ….. [if there was a] neighbourhood dispute, and someone’s capacity was in question, it’s different, but in this case EVERYTHING is related to capacity, and the control issue. If [Mrs G] has litigation capacity, first it’s unlikely that she would lack subject matter capacity… it’s unlikely, if possible; but if the court finds she [doesn’t lack] capacity, she’s in no worse a position, she can choose not to continue and instruct a solicitor of her choosing. The court is still going to be dealing with fact finding – she will just have the right to be protected, as the OS will remain. Of course, it’s any litigation friend’s responsibly, especially the OS, to make sure the court knows what P feels about each capacity area. The court won’t be deprived of knowing what P thinks about each of the capacity areas.” [counsel’s emphasis]

Mrs G had her hand up at this point and the judge invited her to speak: She said: “My relationship with my daughter is terrific [very quiet no microphone in front of her] … I need to be able to carry on… [inaudible]. The judge assured her that she was trying to work out ‘how the hearing about your daughter can be broken into pieces’.

Mrs G: I want to continue my relationship.

Judge: … We are not stopping the relationship – it is my job to make sure it is safe.

After an exchange with Mrs G’s daughter to explain the process of addressing the capacity issues, followed by the fact-finding and the implications of that for contact with her mother, the judge returned to the matter of how to deal with litigation and other capacity issues: “At the moment we are trying to work out HOW MUCH should be done on those days. The OS says only litigation capacity – or the whole lot. [To Oliver Lewis] Can you just explain why the whole lot again?”

Counsel for the Local Authority: It’s very rare for someone to have capacity to litigate and [then not have capacity for other issues] …. My example of the neighbourhood dispute over a fence. Case law suggests capacity has to be looked at in the round. Litigation capacity has to be looked at in relationship to the proceedings [as a whole] – [capacity to decide about] care, contact, make/revoke LPA , and in the Inherent Jurisdiction case, whether she is a vulnerable person subject to coercive control by [her daughter]. In my submission, Mrs G has said to numerous health care professionals she doesn’t want her daughter to be as controlling as she is, when her is daughter not there. Totally understandable, it’s not critical of Mrs G. She’s said the opposite to many professionals. It would be in my submission, entirely artificial and wrong to deal with litigation capacity as if it’s a silo, and unconnected to other areas of capacity. I would say that about any COP matter, but especially where at the centre are these allegations of influence and control. It could be that if the court determines capacity in an omnibus hearing in one day and finds it’s not possible to determine capacity in any or in some of the areas, then it may be that court would direct an assessor to carry out an assessment of capacity AFTER the court has found out the facts. Dr Barker says he didn’t put the allegations to Mrs G because he didn’t know which ones had happened or not. He couldn’t come to a true assessment about capacity …that could be one of the outcomes.

It seems that the Local Authority is saying that the reason they do not currently accept Dr Barker’s (independent expert) capacity assessment (that Mrs G retains capacity for all matters) is because he didn’t put to her the full relevant information about the allegations against her daughter. According to Dr Barker, he did not do this because he did not know which allegations were proven. So, the Local Authority is submitting that his conclusions regarding capacity cannot (yet) be relied upon. And further, that there should be a fact-finding hearing under the Inherent Jurisdiction if Mrs G is found to retain capacity in any matter. This argument confuses me. If the Local Authority is saying Dr Barker’s assessment is not reliable because he did not put the (proven) allegations to her – then how can a capacity hearing (before the fact-find) determine her capacity?

Nevertheless, Mrs Justice Arbuthnot then said: “I am now moving in his [Oliver Lewis’] direction.”

Counsel for the OS tried again: “It’s to do with [Mrs G’s] voice in the proceedings. At the moment, we have been supplied as her litigation friend and obliged to present her case in her best interests. That’s not the same as her being able to instruct as she wishes. […] If it proceeds to inherent jurisdiction, and the court determines she is vulnerable, then the OS can be joined as a party. That’s for the future …. [Judge: Yes] Er … I have made my position clear. I suppose I could live with capacity being dealt with on the same day, but that comes with a health warning… If she HAS litigation capacity, and wants to rely on Dr Barker … does she want me, or someone else? The case is complex and dynamic. I agree we need to separate out the case and … I could live with everything being dealt with on the same day, but it might get more complicated on the day.”

The judge exclaimed: “[It is] such a technical thing. All capacities together or separately. Certainly, fact-finding …. It is SO technical this and very unusual, terribly unusual.” [Judge’s emphasis]

So, an ‘omnibus’ hearing to determine all aspects of capacity in question, including litigation capacity, was planned over two days in July 2024.

6. Mrs G’s daughter, the Inherent Jurisdiction and undertakings

Understandably, both Mrs G and her daughter were concerned about their relationship, and contact. We couldn’t hear a lot of what Mrs G’s daughter was saying, though she was clearly expressing concern about proceedings: “If this continues, we could go round and round”.

The judge clarified: “…there will be a fact finding under the Inherent Jurisdiction. [There are] two proceedings side by side. One Court of Protection [for] capacity etc., the other Inherent Jurisdiction. My powers are to protect someone, even if they have capacity. Capacity is not the be all and end all. I can still protect her as a vulnerable person.” [Judge’s emphasis]

The judge assured Mrs G’s daughter that “a decision will be made” regarding capacity, and that Dr Barker and Mrs G’s social worker will be giving evidence in regards to capacity and then, following a fact-finding, “if I find that bullying has happened” another independent expert (on coercive control and bullying Prof Dubrow Marshall) will be instructed “to make it safer”. The judge qualified this with “I have to be persuaded he’s going to be necessary”.

Earlier in the hearing counsel for the Local Authority had referred to ‘undertakings’ having been breached by Mrs G’s family. The judge dealt with this toward the end of the hearing.

The distinction between an ‘undertaking’ and an ‘order’ is, according to this website:

“An Undertaking is defined as a legal promise to the court to do, or not do, something, which is binding upon the person making it. Undertakings are made where the court is unable to make an order for a party to do, or refrain from doing, something and once an undertaking has been made, it has the same effect as a court order. An Undertaking can only be made with the consent of the party making it, being a key difference to an Order than can be imposed on parties or made by consent.

The form of an undertaking must be signed with a notice setting out the consequences of disobedience so as to be enforceable as if it were an Order. No such wording is necessary to enforce an Order.”

It wasn’t specified which undertakings Mrs G’s family was said to have breached, but Oliver Lewis (for the LA) asserted that “there has been a question of a few alleged breaches of these undertakings … undertakings have had limited effect. There have been no consequences.”

Judge: What does it say about telephone calls, I haven’t got it in front of me?

Counsel for the LA: It says contact shall be supervised until further order.

Judge: It needs to SPELL OUT, it seems to me, that any phone calls are [subject to that]… [judge’s emphasis]

Counsel for the LA: Happy to spell that out for greater clarity.

Judge: I will need someone to type it out and print it out and no one will leave court until they’ve signed.

Mrs G’s daughter said that she was “never told that I couldn’t speak to my mum without being on loudspeaker”. The judge confirmed to Mrs G: “when [you speak on the phone] to your daughter, son-in-law or ex-husband, it needs to be on speaker phone. You can talk privately but it needs to be on speaker phone.” (But it’s not ‘private’ if it’s on speaker phone for carers to hear, I would argue.)

Mrs G’s daughter continued, that Social Services had “completely misjudged our family”, talking about the scrutiny they had been subjected to: “We didn’t know a safeguarding was on, we didn’t know what it meant. [She – the live-in carer] heard words between us and suddenly a safeguarding … they had the wrong end of the stick. [They are] trying to control a frail elderly lady who loves her family, [to] coercively control her, it’s ironic. They write down everything we say, word for word, supervised contact. My mum has stood her ground on multiple occasions since January. She’s been interrogated about her private life with her family constantly. I have been reading transcripts from [Social Worker, plus she listed three others]. Mum has not wavered once. She would not be without us all. … they haven’t seen any coercion.”

Mrs G’s daughter was also very clear that the original diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia was ‘incorrect’: “Whatever you decide …. Mum doesn’t have Alzheimer’s. … It’s a witch hunt on my family … I would like you to give my mum her capacity back”

I don’t think Mrs G’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s has been officially changed, but her previous treating clinician and the expert witness both suggest (in their reports) that she does not have Alzheimer’s disease.

Counsel for the LA raised a final issue for the undertakings – not to mention the possibility of a care home to Mrs G. He said that ‘other allegations’ were distressing Mrs G, and that the Social Worker wants Mrs G to remain at home. It was hard to work out who was alleged to have said what, when, but there was a suggestion that Mrs G’s daughter was mentioning care homes to her mother. She denies this and Mrs G’s husband said that it was the Local Authority that was talking about care homes when Mrs G was in hospital. The judge was emphatic: “NOBODY must mention care homes to her. … The point is DON’T. There’s no point in mentioning it. …” Mrs G’s daughter said something in response that we could not hear and the judge reiterated: “Well it’s not on the table, it’s not proposed, this lady wants to stay at home. It is NOT to be talked about.”

The hearing came to quite an abrupt ending following this exchange – after agreeing dates for further hearings – and what the judge said to conclude the hearing was inaudible.

7. Reflections

This was a very interesting hearing about a difficult case – for all concerned. From an observer’s perspective it covers much of what the Court of Protection is about – whether or not P has capacity for many decisions, including litigation capacity itself; whether, even if P retains mental capacity for any or all decisions in question, she is subject to coercive and controlling behaviour from her family (‘bullying’ as the judge put it) and, if she is, what is to be done about managing contact between P and her family; Lasting Power of Attorney; best interests in respect of all decisions should P be found to lack capacity; and then the possibility of committal for P’s daughter (for allegations which – to us – are not clear at present). All these issues together make it a very compelling case of great public interest.

I was intrigued by two things that Mrs Justice Arbuthnot said in respect of Mrs G’s relationship with her daughter. At one point the judge said to Mrs G’s daughter: “My job is to work out, under the Inherent Jurisdiction, is to work out if your mother can continue to have a relationship with you, safely …. We’ve all had strong relationships [referring to altercations and emotions running high in all relationships]” [my emphasis}. Later, the judge said: “IF I make certain findings – this is a mother who wants to see her daughter and a daughter who wants to see her mother. I wouldn’t want to get in the way of that.” [Judge’s emphasis]

In the first quote, the word ‘if’ confirms that a court order could be made to prevent any further contact between mother and daughter. The second quote seems to suggest the opposite, but I think that the judge is, on the one hand, outlining a possible legal scenario (that the court does have the power to prevent contact between P and specified people) and on the other hand, is expressing a view that she does not want to do this. Mrs G and her daughter were (understandably) anxious about the ongoing uncertainty (Mrs G: “I want my relationship to continue”). The court is following correct procedure, of course: where there is allegation of coercive control and a vulnerable person, this must be taken seriously and looked into carefully. At the same time, the fear and panic that potentially having your mother-daughter relationship ended by court order must be difficult to bear. The judge later confirmed “We are not stopping a relationship; it is my job to make sure it is safe.” I am not sure I would have felt reassured by the end of this hearing that this was a certainty – and I still feel unsure, given the fact that the court will consider coercive control, bullying and potential committal of Mrs G’s daughter.

A final thought on Mrs G’s diagnosis. I wasn’t clear whether this was going to be clarified at the next hearing, either by the witnesses (Dr Barker the expert witness and Mrs G’s Social Worker) or Mrs G’s treating team . It could have been mentioned and I missed it being discussed. It seems to me to be very important, not only for the court case (i.e. the nature of Mrs G’s ‘impairment in the functioning of her mind or brain’ for the purposes of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Section 2), but also for Mrs G herself. Does she have dementia? It was suggested that she was given this diagnosis in 2021 when she was ‘very poorly’ (daughter). It is notable that Dr Barker’s April 2024 report suggested that he had repeated the cognitive tests that Mrs G had previously completed and found that her scores had ‘markedly improved’. This is three years later, which would not be expected if someone has Alzheimer’s dementia. One of the defining characteristics of this diagnosis is ‘insidious onset and gradual progression of impairment in one or more cognitive domains’ [see here]. Diagnosing any dementia is not an exact science, involves clinical judgment as well as standardised assessments and neuroimaging: the NICE Guidelines outline best practice here. Incorrect diagnoses of dementia can be made (see here and here for example) and monitoring of a diagnosis is important because there is no, one, single test to confirm the presence of the disease whilst someone is alive.

The next hearings for the case are on 22nd and 23rd July 2024 (to determine capacity issues, including litigation capacity) and then 2nd – 4th October 2024 (fact-finding regarding allegations of coercive control and ‘bullying’).

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She tweets @DocCMartin