By Celia Kitzinger, 25 June 2023

This is a tragic and seemingly intractable case.

A mother and daughter love each other and want to be together.

The daughter, FP, is deprived of her liberty in a residential nursing home. The placement is some distance away from where her mother lives with her husband (FP’s stepfather) – and where she used to live too.

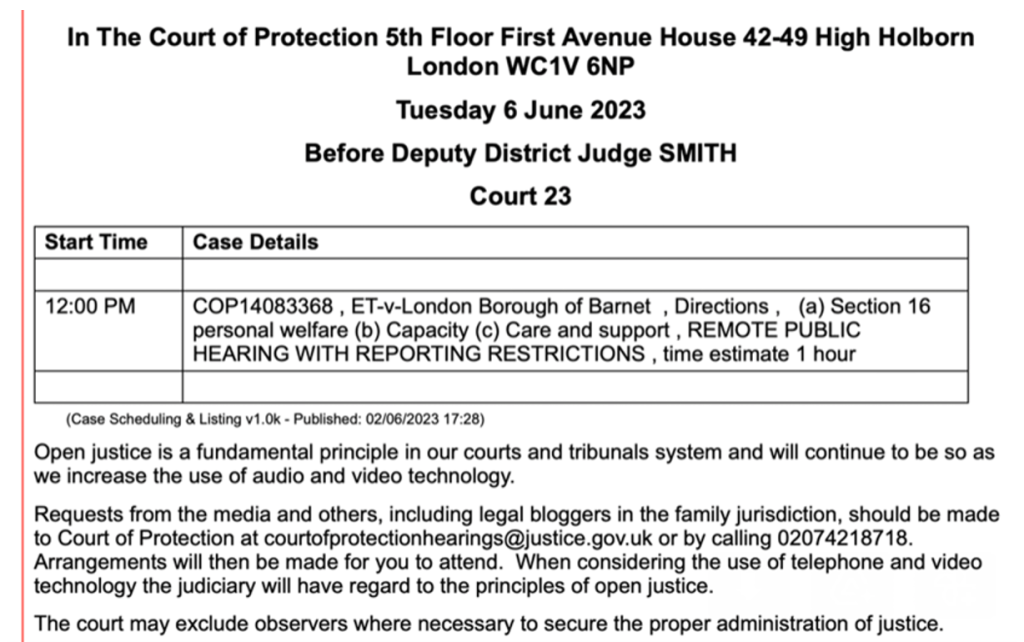

By the time of this hearing (COP 13258625, before Mr Justice Poole, on 19 June 2023), mother and daughter had not been together physically for more than a year. A court order means that they’ve been permitted only short fortnightly (supervised) video or telephone contact – with restrictions on what they can talk about.

The protected party, FP, has expressed a clear and consistent wish to see her mother face-to-face. FP’s mother is clear that she wants to spend time face-to-face with her daughter and “give her a hug”.

It doesn’t look as though that will be happening any time soon.

Background

There’s a long and complicated history.

FP was born and brought up in Russia until the age of 12 when she moved with her mother to the United Kingdom. She was diagnosed with cerebral palsy as a child and now has mobility problems necessitating the use of leg splints, a walking frame, and, for longer distances, a wheelchair. She contracted meningitis in 2011, which resulted in a deterioration in her mental health ultimately leading to hospital admissions under the Mental Health Act 1983 in 2017.

She’s been diagnosed as suffering from psychosis, (subsequently labelled ‘treatment-resistant paranoid schizophrenia’) and experiences auditory hallucinations including that people are going to kill her and harvest her organs. Her mother does not consider her daughter’s mental illness to be ‘treatment-resistant’. She says there is a treatment previously prescribed for her, that has worked before, and would work now, and it is medical negligence or criminal behaviour not to provide her daughter with that treatment. The current treatment is simply (she says) making her daughter worse. By contrast, the Consultant Psychiatrist treating FP says that FP is “medically very stable”. She is said to be more self-aware regarding her mental health, and to be able to make use of ‘self-soothing techniques’.

The case was initially heard by Her Honour Judge Moir (now retired) who handed down a judgement in October 2020. She found that FP lacks capacity to conduct the proceedings and to make decisions about her residence, care and support and contact with others. She also made findings about FP’s mother: that she has an “enmeshed” relationship with FP which exposes FP to high expressed emotion; that she communicates negative and critical views about FP’s care to FP (and to others in FP’s presence); that she is abusive to care workers, seeks to control FP’s care and treatment and attempts to challenge – and has interfered with – her daughter’s prescribed medication; and that contact between mother and daughter is associated with a decline in the daughter’s mental health. She ordered that it was not in FP’s best interests to live with her mother.

There followed a series of orders, first from HHJ Moir and then from Poole J, restricting contact between FP and her mother.

At a hearing, in June 2022 (SCC v FP & Ors [2022] EWCOP 30), Sunderland County Council sought an order for reduced contact. The court ruled that there should be no face-to-face contact for an interim period of just over five months, and that order was later extended in a subsequent court hearing on 6 December 2022 and has lasted now for more than a year. Mr Justice Poole concluded:

“it is contrary to FP’s best interests for face to face contact with [her mother] to continue over the next few months. Whilst FP has said that she enjoys seeing her mother, the overwhelming balance of the evidence is that it is currently harmful to her.”

He also states at that “[FP’s mother] is labouring under an irrational and unjustifiable belief that FP is a victim of a conspiracy of professionals to harm her. This belief is entrenched.” (§34 SCC v FP & Ors [2022] EWCOP 30)).

The last substantive best interests hearing was on 6 December 2022. The court continued the order that there should be no face-to-face contact between FP and her mother and stepfather but supervised video or telephone contact was directed to take place fortnightly, with rules in place for how FP’s mother must conduct herself during these calls. She must not speak in Russian (their native language) and she must not discuss her daughter’s treatment. In particular, she is prevented from entering into discussion with FP about any medical negligence claim, court action, complaints against treatment or against the current or former treating clinical teams, social work team, and placements. She must not talk to her daughter about complaints she has made to the police, CQC, government agencies, politicians, or professional regulatory bodies. She’s also prevented from contacting emergency services. if she does any of these things, the order says that contact between mother and daughter must be terminated.

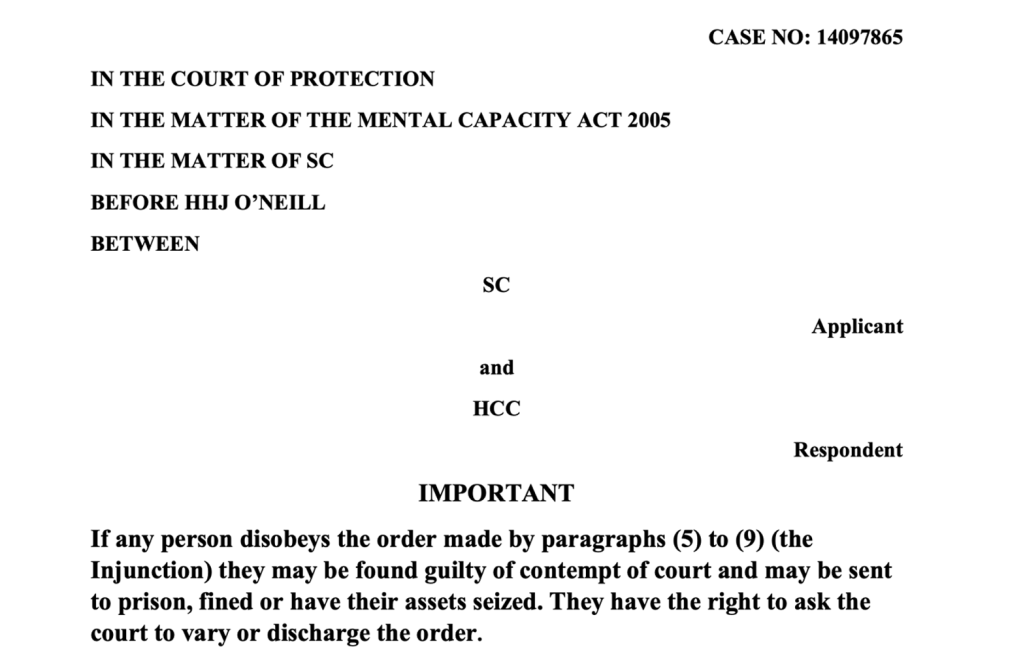

There is also an injunction in place (with a penal notice) saying that she must not audio- or video-record her daughter, or the staff caring for her, or place information about her daughter in the public domain, including on social media. She repeatedly breached that order, posted videos and photographs of her daughter on the internet, and was the subject of a committal hearing. She received a 28-day prison sentence, suspended for one year.

The mother’s view is that the Court is engaged in a cover-up. She says that unqualified people have made incorrect diagnoses and medical mistakes – on the basis of which she’s complained to the General Medical Council and to the Nursing and Midwifery Council about named individuals, and to the Health and Care Ombudsman. She says she has “hundreds of videos to show the degree of distress and deplorable care, but it has been completely ignored by the Court and by the Regulators. This is why I have posted some of the videos on the Internet, just out of desperation, but the Judge ordered to delete material evidence“. (Note: This paragraph has been added in response to her feedback to me on reading an earlier version of this blog post. I am planning to write about the Mother’s appeal against her committal and there will be a great deal more information about this in that blog post.)

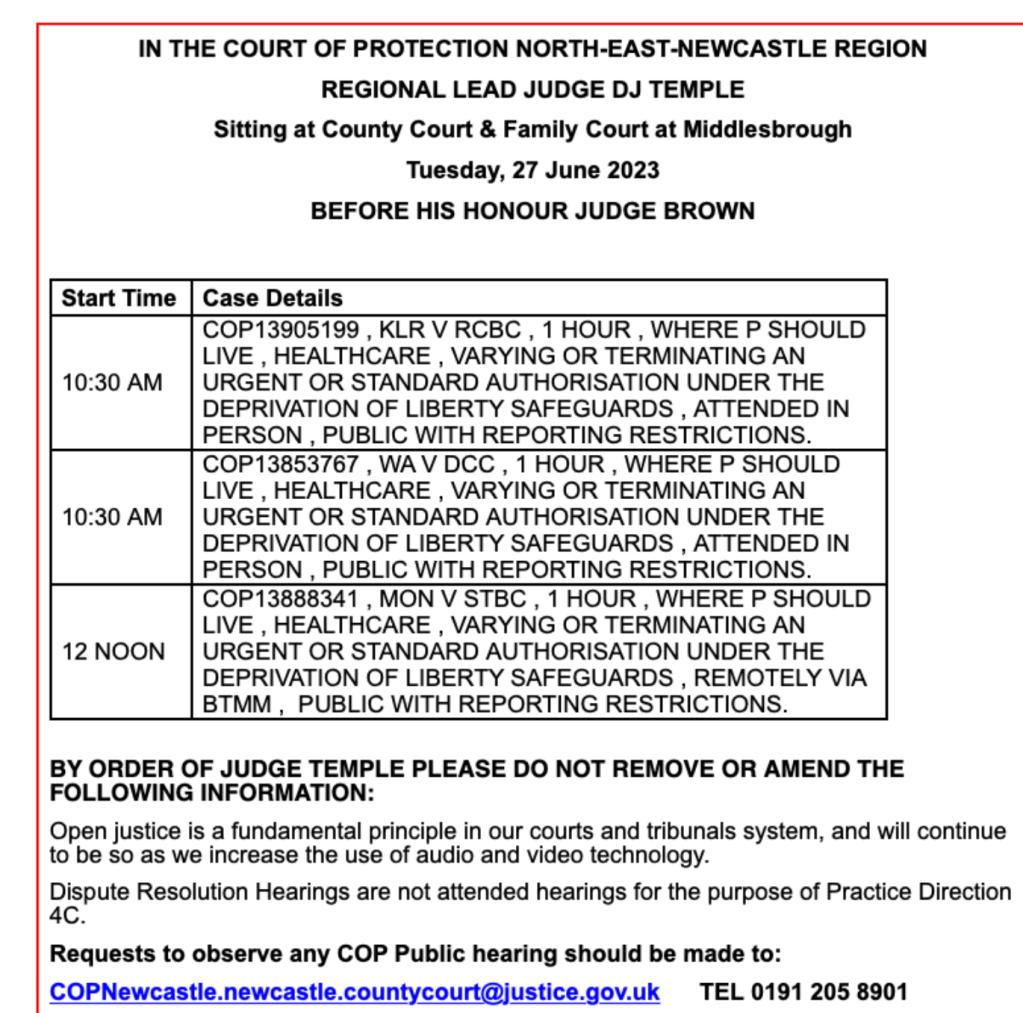

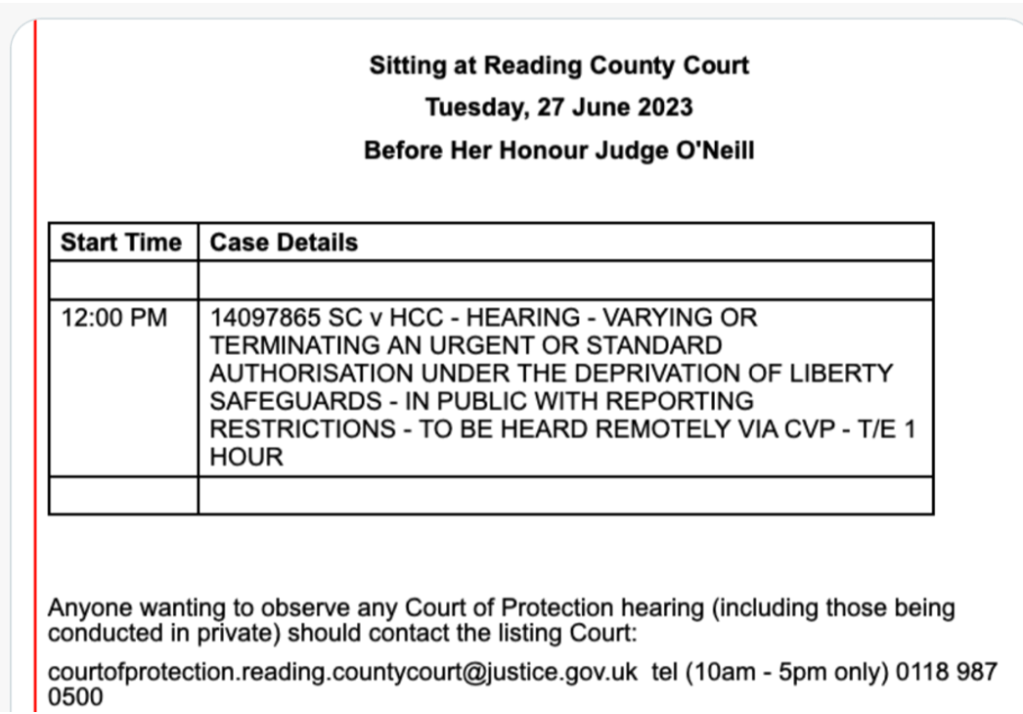

The (remote) hearing today, listed for a full day in Newcastle Civil and Family Courts, is to determine whether the suspension of face-to-face contact should remain in place. There was also mention of a potential change of placement, so that FP could be cared for closer to her mother’s home, and FP is said to be enthusiastic about that because she believes it would enable her to spend more time with her mother. The matter of the placement was not a decision for today, which focused on contact arrangements.

The purpose of this blog post

This is a very long blog post. I have tried to avoid summarising what was said, or glossing people’s positions, or simply outlining the issues and outcome (which is what most legal commentary does) in favour of a moment-by-moment representation of the interaction as it happened, live in court.

I have tried to reproduce every word of what was said (and some non-verbal actions too). This was a big job, and it won’t be completely accurate, because we are not allowed to audio-record Court of Protection hearings. I had to type as fast as I could during the hearing, and in this blog post I’ve drawn on my contemporaneous touch-typed notes to try to get what everyone said as accurate as possible. Of course, I’ll have missed bits – either because people were speaking too fast for me to keep up, or because my concentration failed: when I know I have missed bits I have added “[…]” to the quotation. Sometimes, too, people were speaking over each other which made it hard to hear what was said. But the value of this detailed transcription, I believe, is that we see how a Court of Protection judge goes about the process of ‘doing justice’ and arriving at a decision as a process in real time and not simply via a retrospective account constructed to justify his decisions after the hearing is over.

One important goal in producing the blog post in this way is to capture what FP’s mother (in particular) said in court and to ensure that her voice is heard. This matters, because one of her recurrent complaints is that nobody is listening to her – in court, or out of it. In fact, as my transcript shows, she did get a lot of ‘air-time’ in court. Compared with other hearings I’ve observed with vocal family members who have interrupted proceedings to get their points across, Poole J was extremely tolerant of her interventions (at least until he came to give his judgment). Her complaint must be that the judge did not agree with the points she was making rather than that he didn’t give her the opportunity to make them.

Beyond the courtroom, though, the mother is forbidden, by the Transparency Order (and by the separate court injunction against her) from speaking out in her own name about the court proceedings. The reasoning behind this is that if she speaks about the protected party, FP, as her “daughter”, that would reveal her daughter’s identity, and infringe her daughter’s right to privacy. The parents have told the judge that FP has given permission for her mother to speak out about her – and indeed to make and share videos and photographs of her – but the court doubts that FP has capacity to give that permission.

Unlike family members, I am permitted, as a member of the public observing this case, to write about it, and to name the local authority as Sunderland City Council, so long as I do not publicise anything that “identifies or is likely to identify that FP is the subject of these proceedings and therefore a P as defined by the Court of Protection Rules 2017 (save that FP’s mother may be identified as Louibov or Luba MacPherson and may be named)”. I cannot identify any other family member, or where FP lives or is being cared for – but within those restrictions I am free to report on what happened.

It’s regularly the case that family members are banned by the court’s Transparency Order from speaking about proceedings, while public observers like me are free to do so – and this can be very frustrating for them (see: A ‘bog standard’ s.21A case: Anna’s mum). At a previous hearing, this point was made on the mother’s behalf by her (then) counsel, Dr Oliver Lewis, who quoted from one of the Facebook posts she had made (allegedly in contempt of court) and commented that “If an observer had written a similar article and Prof Kitzinger had posted it on the Open Justice blog, there would be no contempt”[1]. So, in this blog post I have taken care to report the words of FP’s parents as fully as I can. I’ve included long stretches of dialogue (e.g. between the judge and the mother) set out like a ‘play’, as close to verbatim as I can make them. I hope that people who know the family and are concerned about this case will find this useful in arriving at their own assessment of what is going on.

I am very alert to the fact that preventing or limiting contact between family members (or between other people who love each other and want to be together) is a draconian measure that engages and may violate their Article 8 rights to family life. I have seen the Court of Protection make, or consider making, contact restrictions in many other cases – usually as a last resort after multiple warnings. They’ve included cases of ‘predatory marriage’, and abuse within marriage by a wife in one case, and by a husband in another. There are also sometimes contact restrictions imposed by the court limiting contact between adult children and their parents (e.g. here). Many people are horrified that the court can make injunctions to stop contact between family members who want to be together. I believe it is crucially important that these court decisions are properly open to scrutiny and evaluation. That’s why I’ve written this blog post, and why I’ve written it in the way that I have, so that people can make up their own minds about the case on the basis of what was said and done in today’s hearing.

I hope this blog might be useful to everyone who might be embroiled in situations like this: families, of course, and also health and social care professionals, and indeed lawyers and judges facing this sort of situation in court.

Key people in the court

- Local Authority: The applicant local authority (Sunderland City Council) was represented by Simon Garlick of Dere Street Barristers.

- Litigation Friend: The protected party at the centre of the case, the first respondent, FP, was represented – via her litigation friend – by Joseph O’Brien KC of St John’s Buildings. FP did not attend.

- Mother and Stepfather: FP’s mother and stepfather (the second and third respondents) attended as litigants in person (i.e. without legal representation). They were supported by a McKenzie Friend – a layperson providing (legally unqualified) assistance. The McKenzie Friend was (in my experience) unusually active in this hearing, and I have described his role in some detail below.

The hearing

The hearing lasted all day. Even though I’ve watched more than four hundred hearings, I found this one a particularly intense and demanding experience. It must have felt exhausting for those actually involved.

The young woman at the centre of this case (FP) has not been in court in any of the hearings I’ve observed – although the judge has spoken with FP privately, by video-link from her placement. I have watched some of the videos her mother posted (contrary to the court’s orders) on the internet, and found them shocking and upsetting. Her mother was sometimes filming her during very serious mental health episodes. Like everyone else in court, I want the judge’s decisions to be in the best interests of FP – to militate against her distress, and to support her recovery as much as possible. But the parties fundamentally disagree about what is in FP’s best interests.

The burning issue for her mother is FP’s medication. She believes it needs to be changed (back to the medication FP received before, prescribed by her former GP and Consultant Psychiatrist). I understand from FP’s mother that she has submitted two Emergency COP 9 Application Forms in the last six months, addressing the issue of medication change, but they were “ignored”. The Local Authority and the Litigation Friend accept that medication should be decided by FP’s current medical practitioners and believe there is no need for the court to interfere with FP’s medication. The judge did not acknowledge the existence of an application before the court today for any change in medication or for a medication review (nor for any claims of medical negligence or perjury or other issues raised by the mother).

The key issue for the Local Authority, who made the application, was whether it was in FP’s best interests for face-to-face contact with her mother to be resumed. The litigation friend had said it was. The Local Authority thought it wasn’t. That was the question the judge had to decide today.

I’ve structured the blog to reflect the way this hearing unfolded in court, as the parties were given the opportunity to state their positions, and then the final (oral) judgment.

- The Local Authority

- FP’s Mother

- The Litigation Friend

- FP’s Mother (again)

- FP’s Stepfather

- The McKenzie Friend for FP’s parents

- Closing Submissions

- Judgment

1. The Local Authority: Face-to-face contact is not in FP’s best interests

Counsel for the applicant local authority, Simon Garlick gave a brief summary of the case so far (thank you!) and then explained the local authority’s position on contact. In brief, the local authority believes that it is not in FP’s best interests to have face-to-face contact with her mother, but they recognise that it’s a finely balanced judgment and are not unwilling to accept a decision (in line with the view of the litigation friend) that face-to-face contact is in FP’s best interests.

Simon Garlick began by referring the judge to the record of contact on 22 December 2021. It wasn’t read out in court, and I don’t know exactly what happened (or is recorded as happening) during that meeting between mother and daughter, but it was said to “represent a worst-case scenario for face-to-face contact”. From comments made later in the hearing, I think that FP’s mother called for an ambulance for her daughter during the course of that meeting, and that the local authority considers that this was not appropriate behaviour. I think his point here was to explain why the local authority believes that face-to-face contact is not in FP’s best interests, by showing the judge how it can go badly wrong.

He then addressed the possible change of placement for FP, which the local authority also considers not likely to be in FP’s best interests. This wasn’t up for a decision today, but he raised it (I think) to display the concern and anxiety the local authority feels about reinstating face-to-face contact between mother and daughter.

LA: No one is inviting the court to make a best interests decision on this today, but there is agreement between the Litigation Friend and the Local Authority that [the current placement] is a very successful placement for FP, so there would need to be good reason, going beyond FP’s wishes, for her to move. But the process of assessing the possible new placement has to be given careful thought – there is the potential for disappointment and distress. Normally, a protected party would visit the placement. It’s not clear in this case whether that process should be followed. What the local authority would say is the most obvious potential positive for FP would be relatively frequent face-to-face contact with her mother. But we anticipate that even if the court decides today that face-to-face contact should be reinstated, we anticipate that it would be gradual and incremental. It would be some time before the court can assess whether face-to-face contact would be sustainable. The relevance of the placement issue to the main issue before the court today of contact, is that the process of considering where it’s in FP’s best interests to live is one that is likely to lead to a series of expectations and quite possibly heightened emotions. And it’s possible to see that already. There have been occasions during contact over the last few weeks when both FP and her mother have brought up the issue of the change of placement. Going on to contact then, there is a fair amount of agreement between the local authority and the Litigation Friend about how face-to-face contact should take place, if it’s your decision that it should after today. We think contact every four weeks (the Litigation Friend suggests every six weeks) and the Litigation Friend suggests that it should last for an hour each time. We propose 30 minutes initially. In terms of existing video- and telephone contact we note that none have been more than 18 minutes. The local authority considers contact should be conditional upon [FP’s mother] not having electronic devices on her during contact. This is to prevent her from recording FP, and to prevent her from contacting the emergency services as happened on 22nd December as I referred you to. It is important to resolve this today. We do not want to be in the position where [FP’s mother] came to a meeting and refused to hand over her device, and then the meeting wouldn’t take place, which would be very disappointing to FP. We anticipate that this is an issue that [FP’s mother] would need to give evidence on today. We would expect the same restrictions to be in place as currently – she would be required to speak in English and not to enter into discussion with FP about medication, the placement, complaints and so on. We and the Litigation Friend are in agreement that these restrictions should remain in place. Finally, if face-to-face contact is ordered, it should be kept under review, and if parties feel that face to face contact is not in FP’s best interests, then the matter should be returned to court. The Litigation Friend and Local Authority are also in agreement that this is a finely balanced decision. The Local Authority understands the emphasis put on FP’s wishes, and the point made by the Litigation Friend that there’s a danger of the suspension of face-to-face contact becoming a status quo from which it’s difficult to depart. On a fine balance, however, we reach a different conclusion about what’s in FP’s best interests. She’s continuing to grow in confidence and we believe that continued suspension of face-to-face contact will act to enhance her autonomy. The existing arrangements may appear not to promote her Article 8 rights [to family life] but they do promote her Article 8 rights to her private life. She has some autonomy about how she conducts the contact and when and how to end it. The records show that FP chooses to end contact with her mother at particular points. Looking at the written evidence, the likelihood is that in face-to-face contact [FP’s mother] will continue to bring up the same issues she’s been ordered not to bring up, and it will be much more difficult, face-to-face, to redirect her and to protect FP’s limited autonomy, which is likely to be overwhelmed in her presence. But we agree it’s a finely balanced decision. The factor likely to be of most importance is how [FP’s mother] conducts herself. So, if Your Lordship has reached a provisional view about face-to-face contact on the basis of written submissions, we would be keen to know what that view was, and would be inclined to accept it.

At this point, the judge asked FP’s mother, visible on screen, to turn on her microphone .

2. Mother: FP’s medication needs to be changed

After checking that she’d had sight of the most recent court documents, the judge explained the decision he had to make, and the different views of the local authority and the litigation friend, and invited FP’s mother to express her views on this matter.

As best as I could capture it, the exchange went like this.

Judge: For the local authority, Mr Garlick raises the possibility of FP moving to a new care home. The main advantage of that is that it would make face-to contact easier because it would be closer to you. But we haven’t yet got to the stage of deciding whether face-to-face contact is in FP’s best interests. So ,the issue for today is whether face-to-face contact is in FP’s best interests, and if so on what terms. The local authority accepts that it’s a finely balanced issue but continue to oppose it. The litigation friend, on behalf of FP, supports a limited introduction of face-to-face contact. I’ve been asked if I can express a view. I wanted to hear from you first.

Mother: Did you read my statement and my husband’s statement? I don’t know how I can express it more clearly. I am charging this court and everyone who is involved in my daughter’s care with psychopsema. (The judge appears puzzled. She spells it out letter by letter.). This is a special word that is a system of questionable actions that a social service agency might utilise to achieve profit through fraudulent means. I submitted five affadavits to this court, you know, showing that this case is fraudulent. First of all, mental capacity. We are back to square one. Nobody can declare lack of mental capacity permanently. Yet this is what is happening in this court. It’s ridiculous. With regard to what happened on 22nd December, I came to see my daughter and she was in a state. She was over-drugged. Her eyes were popping out. She could not sit down. So, I asked for an ambulance. I asked for recordings to be brought to the court, because all this is medically induced. The court needs to explain why she has not been put on a safe treatment. I have been asking and asking and asking to restore her previous treatment, because that treatment worked. My daughter is unnecessarily suffering. She is in distress every day. She is being discriminated against – her telephone has been taken away; she cannot even call for help. Did you read my daughter’s solicitor’s statement? She states she is being ignored in this placement. How can Mr Garlick state that everything is wonderful and FP is thriving. No. She is not well. And 22nd December needs investigating.

Judge: (tries to speak, finds himself overlapping with Mother and stops)

Mother: May I finish please. Psychopsema is an orchestrated assault, utilizing several methods of fraud, psychological operations, psychological intimidation and other similar premeditated offense-based systems, against a parent, a child or a family. It is often committed by a malicious social worker. If you listen to my daughter’s videos, which I sent to the court, she says the social workers are bullies. The social workers employed by the local authority are using psychopsema to deflect attention away from crimes committed. That is what is going on in this case. Crimes are going on and on and on. I will not see FP until her medication is sorted. Can you sort out her medication please. The social workers and the local authority through their social workers have fabricated this case and we’ve been punished without any justification, without merit, and this is nothing but orchestrated assault. Orchestrated assault. So be warned, pleased. It’s a disgrace. I won’t ever be silenced. I will contact every MP. I will go to Europe. I will go with a group. So many families are affected by this. Who are you, all these strangers, to decide what is best for my daughter – depriving her of everything, even speaking her native language.

Judge: You have made these allegations at a number of hearings. You’ve previously referred to it as “torture” and-

Mother: Yes. It’s all in the medical records. Please study the case.

Judge: Mrs M, will you listen for one moment. You’ve made your position clear on a number of occasions. We’ve heard evidence and I have made findings. You do not agree with my findings. You’ve taken the case to the Court of Appeal which dismissed your application as without merit-

Mother: There are other courts.

Judge: So those determinations made by the court stand.

Mother: I am writing to the Ministry of Justice Call for Evidence

Judge: I have a list here of all the bodies you have contacted – the Legal Ombudsman, adult social care councillors, MPs, the Court of Appeal, you have contacted the police and requested them to prosecute, you have complained of perjury, you complained to the CQC… (there were others in this list but I couldn’t hear them because FP’s mother was talking at the same time as the judge)

Mother: So why you did not consider these concerns? Why you not consider police concerns? I want accountability.

Judge: You have done everything – beyond everything – to challenge the decisions of this court.

Mother: And you have ignored me.

Judge: It’s not been ignored. It’s been considered and rejected.

Mother: Why have you not changed her treatment then?

((I think it was about now, at 11.24am, that the McKenzie friend sent a note to the chatroom asking “for a minute with my client so I can sort this out”))

Judge: Because the position of other people was that the treatment was correct and that was my decision.

Mother: If this is the case, I have nothing to do here until her medication is sorted out.

Judge: Can you be quiet for thirty seconds. We’ve all rejected your view that she is being poisoned by the wrong treatment.

Mother: I have absolutely nothing to say. You carry on. There are other courts.

Judge: In relation to capacity. There has been a finding that FP lacks capacity in relation to the decisions that need to be made. Your daughter has a condition that means she is unlikely to change, and the updating evidence-

Mother: This is against the law. It is against the Mental Capacity Act to condemn my daughter for life. Study the law. Study the law. This is an absolute disgrace.

Judge: I am going to pause in a minute so you can talk to the McKenzie Friend about two things. The first is whether there is any evidence of change in relation to her capacity. Secondly, you said you didn’t want face-to-face contact with FP unless your view of her treatment is accepted. I would like you to have the opportunity to talk to your McKenzie Friend about this. And reflect.

Mother: Excuse me, why are you interrupting me? I let you speak!

Judge: My focus is on your daughter’s best interests.

Mother: (rolls eyes and makes exasperated pswuh! sound)

Judge: I don’t want you to say that you don’t want to see your daughter without considering it carefully.

Mother: Stop this bullying! You know I want to see my daughter. I love her dearly and she loves me. I want to be there for her and to reassure her. But I don’t want to see her in this state. It is very, very, distressing – like on 22nd December. Listen please. You cannot say she lacks capacity based on diagnosis. Where is the proof? ((She mentions different medications, some of which she says are harmful to her daughter)). It’s all written in statements. I don’t know why I have to repeat all this.

Judge: I will give you ten minutes to have a private conversation with your McKenzie Friend (he checks they can do this via a different mode of communication, and explains that they should both mute their mikes and turn off their cameras on this video-platform.)

The hearing actually didn’t resume for almost half an hour. And then the judge asked FP’s mother whether, now she’d had a chance to talk with her McKenzie friend, they could return to the two questions he’d raised with her earlier.

Judge: First, is there any evidence you would like to put before me suggesting a change in your daughter’s capacity to make decisions, especially about residence and care?

Mother: Yes, of course. I advise you to read my daughter’s solicitor’s statement. My daughter knows what she wants. She wants drugs under the supervision of her previous GP. She explains why. This is the doctor she trusts. She put forward arguments with regard to her medical treatment that have been ignored, sadly, in this court. She says she wants to move and she wants to be with her family. I cannot trust any care home. I want social services out of our way. We have been five years in the Court of Protection that did not protect my daughter one little bit. This speaks volumes. Please, I’m very frustrated after five years in court, and I’m asking you please to correct this wrongdoing. This court is nothing but a bullying exercise by the local authority through the social workers. I have reported four cases of perjury from social workers and one case of perjury from a carer. […]. My daughter has had capacity all the way through this five-year process. Her capacity was accepted by another solicitor […] It’s in the court documents…

Judge: All this is from before the court determination that your daughter lacks capacity. The court decision was made on the basis of considering that evidence and the other evidence. You tried to appeal those decisions and were unsuccessful. So, what I’m asking about is any more recent evidence.

Mother: It’s all recent evidence. Five years of accumulated evidence.

Judge: The other point was in relation to face-to-face contact. It’s not happened for over a year. The question is whether it should be introduced. You did say you’d only be willing to have face-to-face contact with FP if her medication was changed.

Mother: I am surprised that you are asking, because it is many years since my daughter was discharged to this “place of despair’ as she calls it. She has suffered (continues to describe more details of “wilful neglect” and “mistreatment”).

Judge: I’m sorry, I didn’t make myself clear. What do you say should happen in relation to face-to-face contact?

Mother: In regard to your question, I’ve been clear about that. I would love to see my daughter, but her medication must be revised by this court.

Judge: I don’t accept that your daughter is being harmed by the medication she’s being given.

Mother: Why you don’t accept?

Judge: That’s been explained before.

Mother: She is a person in distress. How can you- What kind of court is this?

Judge: If her medication is not changed, in the sense that it remains under the control of the medical doctors treating her, then can you (he continues but I couldn’t hear what he was saying)

Mother: (Talking at same time as Judge) Why are you denying her safe treatment?

Judge: (Talking at same time as Mother) You probably can’t hear my question because you are talking.

Mother: She has her own legal rights – never mind her barrister who is in agreement with everything the local authority says. (Continues on subject of medication)

Judge: I have listened to you many, many times on this subject, but my question now is about contact with your daughter. I don’t want to be in the position of planning for face-to-face contact with your daughter only for you to refuse to turn up. That would be distressing for her. Are you saying you will not have face to face contact?

Mother: I do not want to see my daughter in distress, unwell, crying for help. I will accept video-calls, WhatsApp and phone for now.

Judge: Your daughter has said she wants to see you face-to-face.

Mother: I want to see her too. I want to give her a hug.

Judge: May I say something? You are putting an obstacle in the way of seeing your daughter by putting down a demand that it would only take place if there is a change in her medication regime. Please. Take a moment to think about this. Is it in the best interests of FP?

Mother: You deprived her of contact with me for a year. And now you are pressuring me to see my daughter unwell.

Judge: I don’t want to put pressure on you.

Mother: I don’t want to see my daughter distressed. I will see my daughter on video-phone and I will explain that you are not willing to change her prescriptions. You are dictating to us what we must do. You are depriving us. I’ve done nothing wrong. My daughter loves me. I love my daughter. You are interfering with the family unit, and interfering with our Article 8 rights and then imposing that I must see my daughter in this distress. I explain to you, I’ve been there. I’ve seen it. Enough.

Judge: Mrs M, it’s- Will you please be quiet. You are trying my patience.

Mother: You’re interrupting me. You don’t let me get it out.

Judge: Mrs M, you’ve told me that you will refuse to see your daughter face-to-face unless certain conditions are met. So, I have to base my decisions on that.

Mother: (shrugs). Okay. Yes. You’re the judge.

Judge: What explanation will you give your daughter?

Mother: I’ll explain it’s because this court ignores everything. Ignores my daughter’s mental capacity. You are torturing my daughter. It’s a criminal act. I don’t know what I’m doing in this court because you are not listening to me. Can I go? My daughter’s been ignored for one year, because you deprived her of her rights in your court orders. I’m saying it as it is, whether you like it or not.

The judge then turned to counsel representing FP via her litigation friend.

3. Litigation Friend for FP: Supports face-to-face contact but given the mother’s position, face-to-face contact is not an option and cannot be ordered

Joseph O’Brien, acting for FP via her litigation friend said that although the litigation friend strongly supported a trial of face-to-face contact between mother and daughter, they believed it was “finely balanced” and that a “robust plan” would be needed to manage the “risks”. I got the impression that some preliminary work had been done on this plan and to consider how face-to-face contact would work in practice, and how FP would be prepared for it, and supported during it.

But Joseph O’Brien said that, given the “entrenched beliefs” expressed by FP’s mother, and her statement that she will not meet with her daughter unless her daughter’s medication is changed, it seems as though face-to-face contact is not going to be an option.

LF: Before you get to the point of determining whether [face-to-face contact] is in FP’s best interests, you are being told it’s not an option. So, it seems to me that the process of preparing FP for face-to-face contact would not be in her best interests. One reading would be that this is not her true position and that Mrs M is saying this for effect, but you asked her three times, and on three occasions she has said she does not wish for it.

Mother: You are misrepresenting me. You are not addressing the real issues and real crimes.

LF: So, it looks as though her views are genuinely held. So, there’s no point in planning for contact if it’s not going to be taken up. Unless that changes, these proceedings are going to become pointless.

The judge again questioned FP’s mother about this.

4. Mother (again)

Judge: The position you’ve put to me is, you love your daughter and the evidence is quite clear she loves you. She wants to see you, but you don’t want to see her unless your conditions are met with regard to treatment for her schizophrenia.

Mother: That’s not true. The conditions are not mine. It was the previous doctor who recommended the treatment. It’s not true I don’t want to see my daughter. I don’t want to see my daughter in a distressed state. She’s in distress every single day.

Judge: I’m sorry, but that’s not the evidence I have.

Mother: I don’t want to see my daughter suffering. She’s suffering every single day because of medical negligence. So please don’t twist my statement. You’re saying I don’t want to see my daughter, but I do wish to see my daughter.

Judge: I’m going to be honest with you, and straight with you. I am not going to order any change in your daughter’s medication. I am not going to allow you to dictate what medication she is on.

Mother: But the last treatment was working for my daughter, and that treatment is now denied to her. The social worker and local authority vilified me for giving my daughter a spoonful of natural syrup of figs. But look at what they are giving her. If you are not looking at medical negligence, I am not playing games.

Judge: For so long as she remains under medical management with her current medication, you refuse to see her, even though you want to see her face-to-face. Is that right?

Mother: My daughter is suffering on a daily basis, in distress. She says that. She never was in any distress before. She wants to be with her family. I want to be with her. That’s all we ever wanted. I cannot be bothered to repeat everything. Please study the case. This is disgraceful.

Judge: Should FP be told you refuse to see her because you disagree with the way she’s being treated?

Mother: I will explain to her myself. I can do that in English. She will agree with me, I’m sure. I am not to blame. It is medical professionals not treating her properly. Can I have her medication list please. I believe there is criminal activity going on. She is not stable. Can you tell me please her medication list.

Judge: I think you are sent communication about her medications regularly.

Mother: Yes, and I’m sending it straight to the police. One day it will be investigated. Study the case. And don’t blame me that I don’t want to see my daughter. I do want to see my daughter. I don’t want to see her suffering.

Judge: It is your choice not to see your daughter.

Mother: I will fight for her. I will do my best to get her under my care.

Judge: I as a judge cannot direct the medical professionals treating your daughter to change her medication.

Mother: You can order an investigation. This is the Court of Protection and you are not protecting my daughter.

Judge: (to counsel) I don’t think I’m going to persuade, or get any other answer from her.

Mother: The court illegally took away my Power of Attorney and put this unsafe treatment in place. I will explain to my daughter myself that I will never give up until I get justice.

Judge: I don’t want to aggravate you, but I am concerned – and I have expressed this before – about your mental health, because of the way you conduct yourself at this hearing.

Mother: Read the skeleton argument of Oliver Lewis (counsel for mother at a previous hearing)[2]. You are bullying and threatening me. There is nothing wrong with my mental health. There have never been any issues with my mental health, but you or this Family Court, is driving healthy parents into mental problems. Please stop this bullying about mental health. You are not helping my daughter with her mental health.

Judge: I was merely asking a question. I do not want to bully or threaten you.

Mother: At this moment in time, I will not see my daughter because our issues and concerns are unaddressed.

Judge: But those issues have been decided by this court and upheld on appeal and they are not going to change.

Mother: There are other courts.

Judge: You really should assume there are not going to be any changes. So, by saying that you refuse to see your daughter unless there are changes in medication, you will never see your daughter face-to-face, because there won’t be changes.

Mother: There will be changes. Sooner than you think. I will go to other courts.

As FP’s mother was speaking, her husband, FP’s stepfather had indicated that he too wished to speak. He was on the call separately from his wife, using a computer in another room of their house.

5. Stepfather (with interventions from Mother): Medication needs to be reviewed and supervision needs to be relaxed

Stepfather: I just want to try and clear up what [Mother] is saying. We believe FP’s medication is unstable and it shouldn’t be. Nobody is asking for it to be changed. It needs review. By outside people.

I was surprised to hear this. I thought the mother had been exceptionally clear that FP’s current medication was harmful to her. Surely, from her point of view, the only acceptable outcome of a “review” would be that the medication would be changed. The judge seemed surprised too.

Judge: The position that Mrs M has put forward is that there’s a conspiracy to harm FP, so it’s not just a question of reviewing and tweaking the medication.

Mother: (talking over judge): It’s called psychopsema.

Stepfather: It is. I’m on regular medication, and every year I get a message asking me to come in for a review.

Judge: The medication is regularly reviewed for FP.

Stepfather: (laughs) Where are these reviews?

Judge: You should receive them. I previously ordered regular updating communication[3]–

Stepfather: They are worthless.

Judge: Ah, so you receive the reviews, but-

Mother: My daughter is suffering from psychosis and this psychosis is made up. The drug that is prescribed for her has an adverse effect on her.

Judge: Mr M, your wife is saying she’d like to see her daughter, but refuses to do so unless there’s a change in the treatment she’s given. Are you saying that’s not her true position?

Stepfather: What I’m saying is we want to see FP. We do not want to be overmanaged. We do not want to be blamed for causing FP distress. I’ve complained about a large carer. She’s an aggravating devil, that one. We need a bit of breathing space. Please, arrange for FP and me and [Mother] to meet in Macdonald’s with carers sitting on the other side of the room. An unsupervised proper family meeting.

Judge: The concern is – We’ve been over this many times. When Mrs M has met with FP, this has caused distress to FP.

Mother: She’s in distress every single day, and I’m being blamed.

Judge: The beliefs that you have feed into her paranoia. Your beliefs that she is being mistreated feed into her view that her organs are going to be harvested by this mysterious group of people.

Mother: Her other treatment worked for her perfectly.

Judge: It is an unfortunate position that you refuse to see FP so long as she remains under current treatment. It is a very sad situation. I can’t possibly direct that there should be face-to-face contact if you’re refusing to have face-to-face contact unless certain conditions are met. I’ve previously expressed, in strong terms, my view of your views. I’m quite satisfied there’s no evidence of any change in her capacity – and there wouldn’t have expected to be, given the diagnosis of ‘medically resistant schizophrenia’. So, no change in capacity. I’m not being asked to make a decision today about residence, and that would in part be dependent on how face-to-face contact was going. But we have an impasse, because Mrs M is refusing to participate in face-to-face contact unless there are significant changes on her demand, and I have to proceed on that basis. I have to decide what FP is to be told about that.

Mother and Stepfather: The truth!

Judge: Your version of the truth is different. You’re refusing to see her unless you get your way on treatment.

Mother: It’s not my way! It’s the way that doctors recommended for her before. It’s the medication that was prescribed by [Dr X] that worked. Don’t tell her that I don’t want to see her – and upset her more.

Judge: And the second consideration is what order to make. I wonder about the point of fixing a hearing for review, given Mrs M’s position in relation to contact. Her underlying account of FP’s medical condition and how it should be managed has not changed, She remains of the view that there is a conspiracy to harm her daughter – that hasn’t changed. But I was taken aback today by Mrs M’s refusal to see her daughter face-to-face unless the medication is changed.

Following this exchange, counsel for the local authority expressed some concern about FP’s use of (what he called) “Russian Facebook” and the fact that the court has not assessed FP’s capacity to use the internet and has not made any orders about supervising or limiting her social media contact. He said that she communicates with her mother through “Russian Facebook” (the stepfather interjected that this was a poetry site). He said this didn’t seem to be a problem, in the sense that there was no evidence that seeing messages from her mother on “Russian Facebook” caused FP any harm, and he wasn’t actually asking for an order, “but it seems important – this is an issue that has gone below the radar as it were”. The judge responded that since this wasn’t a problem on the ground, and given that there was no relevant capacity assessment, there was no best interests decision to made.

Then there was an hour’s break for lunch.

When everyone (except the judge) returned to the virtual courtroom, the McKenzie Friend asked the clerk to convey to the judge his request for permission to address the court.

6. The McKenzie Friend: A medication review is needed

Official guidance states that a litigant who is not legally represented “has the right to have reasonable assistance from a layperson, sometimes called a McKenzie Friend[4] (MF)”. A MF may “provide moral support for the litigant, take notes, help with case papers” and “quietly give advice on points of law or procedure; issues that the litigant may wish to raise in court; questions the litigant may wish to ask witnesses”.

A MF does not have “rights of audience” – that is, he is not entitled to address the court. The court has discretionary power to allow unqualified persons such as an MF to address the court (Sections 27 & 28 of the Courts and Legal Services Act 1990) but should exercise this power “in exceptional circumstances only and only after careful consideration”. The Guidance states that the litigant “must apply at the outset of a hearing if he wishes the MF to be granted a right of audience”.

At the very beginning of the video-call, before the judge had entered, the court clerk had asked FP’s mother, “I believe you have a McKenzie Friend”, and she’d confirmed that. He subsequently joined the platform and said “hi” to FP’s mother. The court clerk checked who he was and confirmed that he (and I) had been provided with the Transparency Order for the hearing (we had). When the judge joined the platform, he too confirmed that the McKenzie Friend understood the reporting restrictions that apply to this hearing, and the limits of his role, asking whether he had acted as a MF previously. The MF seemed unfazed. He replied that he had acted as a MF many times before.

This is what he said after the lunch break.

MF: Due to obvious communication problems, I am asking the clerk for an audience with the judge to help get these proceedings resolved quicker. It’s unusual I know. I know what they [Mother and Stepfather] want, and I could get this resolved a lot quicker for the judge if he will allow that. I know he doesn’t have to, but I would appreciate it.

After a short delay, the judge appeared on the platform and said that the MF could talk not to him but to counsel, and that he would rise for ten minutes to allow that conversation to take place.

I was not removed from the video-platform while the conversation between MF and counsel took place. I’m not sure whether or not I should have been. But in any event, counsel reported back what was said to the judge, so there are no ‘secrets’ to reveal. The gist of it was that the MF said that what the parents wanted was for reviews of FP’s medication to be regularly carried out by registered medical practitioners, and for those reviews to be shared with them. They were not, he said, asking for an order for the medication to be changed. He also emphasised that they were keen for FP to move to the care home closer to where they live.

When the judge returned, this information was relayed to him by Joseph O’Brien, who characterised the conversation with MF as “helpful”. He pointed out, however, that reviewing FP’s medication was “the responsibility of the Mental Health Trust, who are not a party to these proceedings, and in any case are carrying out regular reviews”. He referred the judge to the minutes of a meeting from 15 February 2023 (in the court bundle), which “encompassed a community mental health team review”. The review led to two primary decisions (he said): “1, to continue FP’s medication without change; and 2, that FP no longer requires a Community Team Care Coordinator”. It seems that the parents had not seen the minutes of that meeting, and that it wasn’t made available to them until they were sent the court bundle. Joseph O’Brien said that as litigation friend he “can see it would be helpful, when the community mental health team carries out its reviews – typically every six months – for a record of that meeting to be sent to [FP’s parents]”.

The mother intervened:

Mother: I will send them straight to the police.

Judge: I’ve seen your responses.

Mother: Why you do nothing?

Judge: I am satisfied that you are getting regular reviews. Please be quiet now. Please don’t interrupt.

7. Closing Submissions

There was nothing really as ‘formal’ as closing submissions, but all the parties wrestled with where to go from here.

The local authority suggested increasing video-contact (in lieu of the refused face-to-face contact) from fortnightly to weekly: “it is hoped that more frequent remote contact might assist Mrs M in reconsidering her position on face-to-face contact. I say that without a great deal of logic to support it. But it’s possible.” Rather than asking the judge to make a final order today, the local authority suggested another (2-hour) hearing in December 2023 (so in six months’ time) to review the situation and “if the court agrees, the court should record on the face of the order that if there is no movement from Mrs M at that point, and she’s still refusing to have face-to-face contact unless her demands are met, that the court envisages that as a final hearing”.

Mother: It’s not ‘my demands’. It’s the demands of my daughter. The demands of the previous doctors.

Judge: Please don’t interrupt.

Mother: It’s just unbelievable. Let’s all drag on for another six months!

The judge said that “but for Mrs M’s position, I would have been minded to introduce face-to-face contact on a stepped basis, and on the understanding that if there was behaviour that was harmful to FP that the matter would come back to court. But face to face contact is not possible at present because Mrs M has placed a condition on it that the court does not consider to be in FP’s best interests”.

The litigation friend raised a question with the judge about what Mrs M “is actually asking for”, saying “I think you need to revisit that again”. He raised the possibility of ordering a Section 49 report, “which could be a review process, although that’s not what s.49 was designed to do”. Again, FP’s mother intervened to say “no, no, no, no you are wrong. These updates only confirm that my daughter is suffering. I am asking for a medication review”. Joseph O’Brien concluded his address to the judge by saying “I don’t see anything against you saying that we all thought it was in FP’s best interests to trial face-to-face meetings with her mother, but they’re not taking place because of the unreasonable position taken by her mother. If she changed her mind, contact could be arranged without a return to court, but with a December hearing listed as a backstop. This is her self-imposed prohibition on face-to-face contact”.

Before making his oral judgment, the judge made an attempt to engage with FP’s mother (I suppose technically to allow her to make a ‘closing submission’). She said again that she was not willing to have face-to-face contact with her daughter “until the court explains why it is not prepared to listen to Dr X, or Dr Y [who recommended the medication which her daughter is not receiving], and why the court is refusing to see that my daughter has capacity”. She told the judge to “Please study the law” and said, “See you in another court!”. He made one more attempt:

Judge: What is proposed is that, since you refuse-

Mother: I am not refusing anything. This court has a duty of care, a duty of accountability. You have to answer for all these crimes hidden in secrecy. I will not be silent. It is not right that my daughter is suffering under dodgy treatment.

8. Judgment

There was no indication that a judgment would be published or made publicly available, so I’ve recorded as best I can what Mr Justice Poole said in his oral judgment. Some of what he said was read from the documents before him, and this meant he spoke relatively quickly, and there were bits I missed.

Judge: I am concerned again with FP. The court has previously determined that she lacks capacity to decide about residence, contact, care and to conduct proceedings. Not only is there no evidence of any change that would affect her capacity in relation to these matters, but also there’s an assessment of 23 May 2023 on page 1679 of the bundle, in which the treating doctor affirms the assessment of FP’s capacity. She says FP has ‘chronic paranoid schizophrenia’. It has been resistant to treatment. [….]. FP is under 24-hour care and supervision. She has chronic paranoia and hallucinations. She can be vocal, and has scratched staff and pulled out the hair of staff. She believes robots are attacking her. There is a high risk of non-compliance with care and self-neglect if she does not receive this care and supervision. She says the people of 2019 are coming to get her. She thought they might be FBI. This group of people are a delusion: she says they can see through her skin and are out to harvest organs from her. The doctor continues by saying FP is bright and reactive with florid psychotic symptoms. She has settled in well at the placement and is cooperative and compliant. My comment is that this is obviously an improvement in her previous condition, and anyway there is no alternative placement available at present. It is sadly true that when FP was looked after by her mother at home, she suffered an acute deterioration.

Mother: WHAT?! (shakes head in apparent disbelief)

Judge: Following the reasoning set out in the published judgments, it was determined that face-to-face contact was detrimental to FP and contrary to her best interests. It was agitating to FP. In addition, [FP’s mother] has been found to be in contempt of court for breaching injunctions that prevented her from recording FP and posting those recordings on the internet for others to view. That is dealt with, but it is part of the backdrop to this case. Mrs M’s belief is that FP does not have an underlying mental health condition-

Mother: Not true!

Judge: Please don’t be discourteous. Please let me finish. The mother’s belief is that FP does not have an underlying mental health condition-

Mother: (laughs) You are saying that my daughter has no legal rights-

Judge: I really don’t want to do this today. (Mutes FP’s mother. I can see her continuing to speak as the judge continues with his judgment)

Judge: Mrs M’s belief is that FP does not have an underlying mental health condition. She believes there is a conspiracy involving professionals directed to deliberately causing harm to her daughter by her medication. She has referred to it before as “torture”. She referred to it today as ‘psychopsema’ (he read out the definition she had provided). That is her entrenched belief. And upon that belief being communicated to FP, it feeds into FP’s paranoia and causes her agitation and distress. So, with great regret, the court – approximately 12 months ago – terminated face-to-face contact. […]. In December last year, I directed that it was in FP’s best interests that video-contact should be offered in addition to phone contact. All reports are that FP is more settled since face-to-face contact ceased. She’s been engaging in more activities. She’s made friends with another resident. She has good relationships with staff. She has a degree of medical stability.

However, FP has a very strong bond with her mother. She wishes to see her. She wishes to move home with her mother, or at least to move to a home near her mother. It is possible that this might become available in the future. But it would only be in her best interests to disrupt her by moving her from her current placement if face-to-fact contact were established as being in her best interests.

Prior to the hearing, the Local Authority view was against face-to-face contact because of the disruption and distress it would be likely to cause to FP. It is much easier to control Mrs M remotely [by muting her], as I have very reluctantly done now. If it were to be reintroduced, the Local Authority says there should be conditions: (1) it would be fortnightly; (2) for no more than an hour, or perhaps 30 minutes; (3) the conditions for contact would include not bringing electronic devices to the meeting, not contacting emergency services, and the other existing restrictions that apply to remote contact should apply to face-to-face contact, including speaking in English. This is not to isolate FP or to strip her of an important cultural heritage, but rather that Mrs M has used contact to convey messages, ideas and beliefs to FP that have been agitating and distressing for her, and she can do that without those present – who don’t speak Russian – knowing what is being communicated. And (4) face-to-face contact must be kept under review.

The view of the Litigation Friend is that it is in FP’s best interests to be reunited with the mother who she loves. And that is what she wants.

My view would be that reintroduction of face-to-face contact would be in FP’s best interests, save that her mother has made it clear at this hearing that she will not engage in face-to-face contact so long as FP’s medical management continues in its current form. There has been an attempt to reframe that as a request for “reviews” of the medication, but Mrs M has made it clear that she is referring to a change of medication – medication that Mrs M believes is being used criminally to harm her daughter, and she has contacted the police in respect of the social worker and the medical professionals.

I have considered whether the condition she seeks to impose can be met in FP’s best interests, and I am quite satisfied that it cannot. FP does have a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. She requires medical treatment. The treatment she is receiving is not capricious. It’s been thought through and it is regularly reviewed. I will never persuade Mrs M, perhaps Mr M as well, of that position, but that is the overwhelming evidence in this case. I cannot direct that medical treatment should be changed in accordance with Mrs M’s views – and I am not prepared to do so.

Mrs M has had the opportunity to reflect on her position and remains of the view that she will refuse face-to-face contact with her daughter unless her daughter’s medication is changed. This means that face-to-face contact, sadly – and it is sadly – cannot take place.

In these circumstances, I have to consider the future management of this case. The position now is that it is no longer the view of the court that face-to-face contact is not in FP’s best interests. In terms of review, if Mrs M were to change her position and agree to face-to-face contact without the conditions she’s sought to impose, the parties are in agreement that contact could be reintroduced on the conditions that Mr Garlick has referred to. The court may be content for that to continue without returning the case to court, but as a backstop I direct that there should be a hearing listed for December, for half a day.

Meanwhile, in relation to remote contact, the Local Authority has reflected on this in the course of this hearing and are agreeable for remote contact to be increased from once a fortnight to once a week. I am satisfied that it is in FP’s best interests to have that remote contact, on the same terms as before ordered, once weekly.

The terms of the order of December 2022 will continue, subject to the changes just indicated. But in terms of injunctive proceedings, there is no longer an injunction that she should remove recordings of her daughter from social media because the Local Authority is satisfied they have already been removed. But the other injunctions remain. Mrs M must not make or post recordings – audio or video – of her daughter, or staff, and must not publicise the proceedings (including via social media).

Finally, I want to address the conduct of this hearing. Very unusually I have accepted – in order to achieve conclusion – disruption, interruption and, frankly, discourtesy. I have done so in order to get through this hearing and get to a conclusion in FP’s best interests. And that has been my focus as I have allowed these interruptions, disruptions and discourtesy to continue. I am far from accepting that this is acceptable. I don’t know the reason for Mrs M’s behaviour. When I asked a question about it, she made it clear she thought I was bullying her and putting pressure on her. She has behaved in a similar way at all previous hearings. Her behaviour makes it difficult for everyone to focus on FP’s best interests, but I am satisfied that this has been done.

And that was the end of the hearing.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, and has personally observed 450 COP hearings since 1st May 2020, and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and tweets @KitzingerCelia

End notes

[1] That’s not actually correct, since the Facebook post names the protected party (FP) and also names past and present carers. But even with that information removed, it’s still the case that FP’s mother would likely be found to be in contempt of court for posting it, whereas I would not.

[2] In that Position Statement, Oliver Lewis quotes from a letter Mrs M wrote to the judge in which she says: I must also comment on the dangerous, misguided and vindictive comments about my mental health. Not only is it very wrong, but it is also discriminatory in its ignorance of the Slavic people and their normal emotional behaviour. “High expressed emotion” is a natural part of Slavic make up and is being mistaken for concerns, the need for answers, frustration at the immovability of mindless persons has nothing to do with anger or bad behaviour.’

[3] According to the Local Authority, FP’s mother has been provided with monthly updates which include details of her daughter’s physical and mental health, her activities, her medical appointments and the administration of any prn medication for physical or mental health.

[4] The name “McKenzie Friend” derives from a legal case from 1970 called McKenzie v McKenzie. This was a divorce case and because the husband was unable to afford to continue using solicitors, those solicitors, for free, sent someone (Mr Hangar) to represent him in court. Mr Hangar was not entitled to practise as a lawyer in England – in fact, he was a barrister qualified in Australia. The court refused to allow Mr Hangar to assist Mr McKenzie in court, and insisted upon him sitting only in the public gallery. When Mr McKenzie’s case went badly, he appealed to the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal held that the judge had been wrong: Mr McKenzie should have been permitted to have this assistance in court, and a re-trial was ordered. (From: “McKenzie Friends in court: Just beware the risks”).