By Bonnie Venter, 23rd February 2021

Editorial Notes: (1) A tweet thread about the hearing is available here. (2) The judgment has been published here. (3) A different perspective on the same hearing (by Bridget Penhale) has been published here.

There are moments in life that cause a monumental shift in who we used to be and who we are today. I know from personal experience, that it’s a life-altering event when a daughter hears about her dad’s untimely death. There is a split-second, a moment, where the world goes quiet, and you realise that life will never be the same again. In effect, a large part of who you were before this tragic event passes with your dad.

Observing this hearing, I bore witness to how the lives of three courageous young women in Canada were transformed when the decision was made that it was not in their father’s best interests to continue life-sustaining treatment.

The hearing (COP 13712297 Re: TW before Hayden J) was split over two days – about an hour and a half on Wednesday 10th February 2021, and then a full day on Friday 12th February 2021 – so about seven hours in total.

Background summary of the case (Wednesday)

When I logged in on Wednesday, my MS Teams screen was dominated by the legal representatives and judge: Nageena Khalique QC (for the applicant Trust, who gave an opening summary), Bridget Dolan QC (for TW, via the Official Solicitor) and Ian Brownhill (for TW’s brother, the second respondent – on behalf of the whole family), and of course Mr Justice Hayden presiding over the matter.

TW is a 50-year-old man who was admitted to hospital following a stroke on 17th December 2020. On 29thDecember 2020, he suddenly deteriorated and was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. He was intubated and then given a percutaneous tracheostomy to insert a breathing tube through his neck. He remains reliant on ongoing mechanical ventilation and has not improved – may in fact have deteriorated – in the six weeks since then. He is in a coma. The question before the court (as in well-known cases like Bland, Burke and more recently Aintree) is: is it in TW’s best interests to continue life-sustaining treatment?

The Trust’s position is that TW’s neurological prognosis is very poor and that continued respiratory support and/or treatment (including CPR and ICU interventions) are invasive and burdensome. The Trust believes that it is not in TW’s best interest to continue life-sustaining treatment and they have submitted a detailed staged plan for withdrawing it, and administering palliative care.

The family[1] opposes the Trust’s application for withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. They believe that TW is aware when the family speak to him and that he is responsive to their voices; and they want to know whether it is impossible – as opposed to highly improbable – that he will recover. If it is impossible the family will accept withdrawal of treatment, but if it is merely improbable, they feel dutybound to ‘fight’ for him. This position comes from the unified voice of his brother and wife (the latter not a party in the proceedings, but present as a witness). Mr Justice Hayden reiterates the fact that TW is at the pinnacle of the case: ‘the case needs to be driven by the medical, the ethical and the welfare interests of P’.

His powerful statement a few minutes before the end of the hearing (addressed to the family members present in court) remains in the back of my mind for the rest of the day:

‘It is not helpful to think of this in terms of fighting. Fighting is not what this is about – it is about care, about love and about identifying best interests and working cooperatively to advance them. Fighting for human dignity is just as important as fighting for survival.’

Lasting Impressions: the value of life, dignity, and organ donor registration (Friday)

My observation on Friday starts off with the obstacle of gaining access to the hearing. It took repeated emails to the Royal Courts of Justice email address (no reply), a few DMs to Celia Kitzinger, and her intervention with emails to the judge’s clerk and to counsel. I felt lucky to get in (I heard afterwards that many others were denied access) but it feels as though gaining access to a hearing listed as ‘in open court’ really shouldn’t be this difficult, and I was disappointed to learn that I’d missed the first clinician giving evidence and being cross-examined. The judge was also distracted and annoyed by late admissions to court.

I will not go over the legal and clinical facts of the case in this blog: the approved judgment sets these out clearly and the blog post by Bridget Penhale (here) also covers these. Instead, I would like to share the aspects of the case that made a lasting impression on me. These are:

(1) What makes life worth living?

(2) The question of ‘dignity’; and

(3) The issue of TW’s organ donor registration.

- What makes life worth living?

For most of us, there is some point in life where we ask the question: what makes life worth living? For people like me who are involved in medico-legal work, this question is often one that might be a central focus of our work. I am well aware that I have personally spent countless hours, bent over literature, searching for the answer in ethics, philosophy and sometimes even novels. Yet, none of these readings provided me with the insights I gained by watching this hearing.

This question was first touched on by Prof D, a Professor of Intensive Care Medicine. He said that TW would:

‘… never return to a state of being where he has some control over his circumstances, where he’s aware of his environment, and would be able to interact with others, be able to direct what would happen to himself, be able to participate in those things that make life worth living – family, friends, joy, the future’.

Prof D answered counsel’s questions about TW’s clinical situation and made it very clear that in his view it was ‘impossible’ for TW to recover. The judge asked:

“Just so that the family are clear what we are talking about…. If, for the sake of argument, it were possible for there to be some improvement in his level of awareness, that would carry disadvantages as well as possibly perceived advantages, and I think it would be helpful to engage in that hypothesis.”

Prof D restated:

‘he might, although it is highly improbable, achieve a level of awareness where he’d be conscious of the fact that breathing was difficult, that moving was difficult – if not impossible – , where he knew that he couldn’t communicate, he couldn’t participate, he couldn’t give his brothers a hug or show love to his daughters. I think it would be a life of considerable distress…’

For this medical expert, it is our ability to interact with others in a meaningful way that makes life worth living. Throughout the hearing, from different perspectives and perhaps phrased in different ways, it was often reaffirmed that hugs, love, and the ability to spend time with our loved ones (especially watching football!) were the things that made life worth living for TW.

Whilst I was listening to the different views expressed on the value of life, I could not help but think about my own life and ask myself, ‘what really makes life worth living for me?’ I confronted this question recently when completing my Advance Decision with the help of the Compassion in Dying website. At the end of the form, there is a space provided to explain your reasons for wanting to refuse some treatment under some circumstances. I instinctively started to write about the significant value that I attach to living an autonomous and independent lifestyle, that I find joy in being physically active and most importantly that my ability to engage with ideas, think them through and have debates with my friends and colleagues constitutes a large part of who I am. I know that I would not be content to live in a state where my brain was not fully functioning. I live for teaching, learning and research – take away these parts of my life and you will be taking away a major part of me. Obviously, I appreciate that this is not everyone’s view: some of my closest friends are perfect examples of how one’s life can be made worthwhile and enriched by having a loving marriage, being a parent or simply having the freedom to be a wanderer. But this is me!

I wondered whether there were certain states of being that I could learn to accept given the necessary time to adjust? I thought about my late father and I know that his response would have been similar to those mentioned above. Love and hugs are what makes life worth living – he was a firm believer that a hug could fix absolutely any problem (to be fair, his hugs probably could)! I relate to my dad on more than one level, but this is one key point where we differ. Hugs and being loved are definitely added niceties to my life but I would struggle to adjust to a life where I am unable to engage with the things that make me tick – be that critically engaging with a medico-legal topic, running, singing along to a favourite song, or painting.

One of the treating clinicians said of TW: ‘We’re keeping his body alive, but not him”. Would I personally want to receive life-sustaining treatment if I were in a similar situation as TW? The answer is a firm no. I’m glad that, prompted by my observation of an earlier COP hearing (which I blogged about here), I’ve now made my own Advance Decision, specifying my own position on what makes life worth living for me. Without documents like these, the Court of Protection is faced with a difficult task when it has to evaluate whether – given what kind of life it would permit – a person would want to receive life-sustaining treatment. It seems safe to say that there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Each person’s personality, values, beliefs as well as medical prognosis presents a new challenge for the Court.

2. The question of ‘dignity’

The question of ‘dignity’ arose as a response to a request from TW’s daughters. It was difficult to see how exhausted and grief-stricken these young women are: I admired their bravery. They asked whether (given that he isn’t – as far as anyone can tell – able to feel pain) doctors would continue to provide life-sustaining treatment for another three weeks, to give the daughters time to fly from Canada to England, quarantine for 10 days, get tested for covid, and get to their father’s bedside for a final goodbye. One said:

What is the harm in keeping him on a little bit longer? So we can get the chance to see him, have that face-to-face connection even if it’s for the last time. I just think he deserves that time. He would want us to have that opportunity…’

Another daughter pointed out: ‘My dad would never want to leave a world where his daughters couldn’t hold him or be with him even if it is for one last time’.

After their statements, there was a moment of silence in the court. A mere glimpse at the screen showed how everyone’s hearts were breaking for these young women’s loss. Mr Justice Hayden, clearly moved by their statements, said: “Let’s take a couple of minutes to reflect. Let’s allow everyone to catch their breath for a few minutes”: there was a 10-minute adjournment.

On return, the question of ‘dignity’ became explicit. Mr Justice Hayden summarised what the daughters had said and its implications:

‘This is what their Dad would have wanted for them – to have been able to say a physical good-bye. I know it’s not been possible for many people in the world to be able do that. But I think it is important to inquire into whether it’s possible here, having regard to the objective: to maintain TW’s dignity in that process’.

What I saw happening here was a concern to address the full of ‘best interests’, which does not refer only to what the person wants for themselves, but also to what they want for others. When I’ve discussed the definition of ‘best interests’ with Medical Law students, there’s often a concern about the lack of a firm definition and some questions about whether the concept of ‘best interests’ is too loose and woolly for the courts to apply it easily. From what happened at this point in the hearing, I realised the importance of allowing certain areas of the law to be flexible and adaptable.

The question of what TW would want not only for himself, but also for his daughters, was now set alongside the question of his ‘dignity’ in the best interests assessment.

One of the treating clinicians was asked to address the daughters’ request: could TW be given life-sustaining treatment for another 3 weeks because his daughters’ wishes to be physically present at the bedside would be an important consideration for him, and should therefore feature in any best interests decision about him?

The doctor was in a difficult position. It cannot be easy to have to explain in precise detail to the family what TW’s body is being put through, which he labelled as ‘undignified’ (the vomiting and bleeding caused by artificial feeding etc). Plus, he said, “the risk of him passing away over the next few weeks is high, even if we were to continue treatment”. To keep him alive might require CPR, which the doctors were not willing to give. Mr Justice Hayden put the daughters’ case as strongly as he could (not least because they were without legal representation in court, the view of TW’s brother – represented by Ian Brownhill – being rather different).

“They accept there will not be recovery. They appreciate that in medical terms their father’s life has become futile – without medical hope. But their case is that an evaluation of his best interests requires sometimes achieving that which he would have wanted even if that is at the compromise of his dignity objectively assessed. So it’s not a situation where CPR is being canvassed purely because the girls want to say goodbye. They believe that their father would want them to be able to say goodbye. Attempted CPR might be contrary to his medical interests at this stage. But best interests is a wider canvas. It’s about who he was, what mattered to him, the code by which he lived his life. … One thing is manifest: he is the centre of their world and they are the centre of his world too. If I put best interests in that wider context, beyond the merely medical, even at the compromise of his dignity, is CPR a viable possibility? I put their case in the best way I can because I want them to have that case put.” (Hayden J)

Another treating clinician who had left the hearing, then reappeared in court, and Mr Justice Hayden filled him in on developments and pursued with him the idea that “it would be a facet of his human dignity to go in the circumstances that he would want to, with his daughters around him”. Acknowledging that it may not be practically achievable, the judge said:

“.. but the question is: is it right, ethical, and in Mr TW’s best interests to see if it could be achieved? […] Human dignity lingers beyond consciousness. It’s in the love of a family and the care and professionalism of doctors and nurses. The question is whether it’s worth an attempt at this because we give human dignity a greater weight than we would in other circumstances.”

The consultant who had re-entered the hearing said he would “struggle” with giving that one aspect of TW’s ‘dignity’ (his wish to have his daughters at his deathbed) such great weight in the context of a best interests decision:

‘The way he is being dealt with at the moment is as sensitively and as best we can. But I don’t think it is particularly dignified and with each day this goes on it becomes more undignified. In a sense what I’d say to his daughters is “remember your dad the way he was”’.

The recuring theme of ‘dignity’ intrigued me during this hearing. My legal training took place within a different jurisdiction that places a strong focus on human dignity as a constitutional right. The South African Bill of Rights explicitly states that ‘everyone has an inherent dignity and the right to have their dignity respected and protected.’ Human dignity, alongside equality, and freedom also forms part of the cornerstone upon which South Africa’s democracy was founded. Due to this, I’ve been conditioned to think of dignity as a right as opposed to a value and this has perhaps allowed me to shy away from thinking about dignity in a non-intrinsic manner.

Listening to Hayden J, I began to reassess the meaning of dignity, especially within the framing of a dignified death. After the hearing, I sought out (via Twitter) some help in thinking through this issue and was fortunate enough to be able to talk for an hour with Dr. Peta Coulson-Smith (@DrPetaCS), a Paediatric Registrar who also teaches Clinical Ethics and Law. She helped me to realise the importance of conserving dignity – and the reality of what that means – both in palliative care and when providing life-sustaining treatment.

As a non-clinician listening to the clinical evidence during the hearing, I only picked up on the basics – artificial nutrition and hydration, ventilation, CPR and dialysis. In end-of-life cases, these forms of treatment are often painted as being undignified and that is understandable since the treatment is futile and will only add to the patient’s suffering with every passing day. But these treatments are not inherently undignified, if they are chosen, or accepted or actively requested by a person for whom these treatments offer hope of life, or a better quality of life. As Hayden J said, “there are people on ventilators out and about in the community, but these are often people who are in charge of themselves”. For many people, ‘dignity’ is about ensuring that they receive treatment at least as much as having the right to refuse it.

Drawing on personal experience, I have a friend who is receiving dialysis while she waits for a kidney to become available for transplantation. Another friend had a PEG for almost a year to help her to gain weight for her lung transplant. Do they perceive these treatments as an affront to their dignity? The short answer is no. The reason being that they are in a position where they have ‘control’ over the provision of the treatments – they have the final say in accepting or refusing it. To them being treated in a dignified way is strongly attached to their personal sense of agency and autonomy.

I suspect that the significance of ‘dignity’ is different for different people, depending on aspects of their lives that they cherish most. Dignity is a term that I hear being used in an under-theorised way in the medico-legal environment, when in fact, as this court hearing illustrates, its meaning is contested. I would love to see more engagement with ‘dignity’ to developer broader understandings of what it means to each of us and the meaning it ought to have within a judicial setting.

3. TW’s Organ Donor Registration

From the first time that I heard about organ and tissue donation, I knew I wanted to be a donor – it seemed the obvious thing for me to do; what would I do with my organs after death anyway? Perhaps my attitude towards organ donation was somewhat influenced by the feeling of immortality that a teenager possesses. Either way, almost two decades later and numerous experiences of witnessing the improvement of the quality of life of recipients post-transplant, my decision to be an organ donor remains unchanged. Therefore, I was rather intrigued by the fact that the act of registering as an organ donor was a feature in this hearing – although that is not, as it turns out, evident from reading the approved judgment[2].

Prof D was the first to refer to TW’s organ donor registration, ‘This is a man that is on the organ donation register. He has the commitment to want to help other people in the event of his death…’

TW registered as an organ donor on the 25th of April 2019, at a time when England was still operating under an opt-in system. This simply means that TW had to actively take the necessary steps to indicate his wish to become a donor: this is usually done by means of registering with the NHS. (This was before the current system of deemed consent that came into force in May 2020 in England (Wales made this shift in 2015): with deemed consent, all competent adults are potential organ donors when they die, unless they specifically registered their wish not to be.

For Prof D, the organ donor card was “a glimpse into his personality. This is a man who cares, he cares for others.’ His daughters added to Prof D’s inference shortly after when they were asked whether they were surprised that he’d registered as an organ donor (since both his wife and his brother had expressed great surprise about this, saying that it was against their religion). One simply said ‘…he’s a kind person, he was selfless in those kind of ways. That is what he would have wanted. I cannot be a hundred percent sure but that’s my opinion’.

The fact that different members of the family had different views about whether or not TW would have wanted to be an organ donor is a familiar occurrence in organ donation settings. Specialist nurses (transplant co-ordinators) and clinicians are often in a situation where they have to navigate complex family dynamics. The family of the organ donor plays an extremely important part in the donation process. Even now under the new deemed consent system, families are consulted and asked to support donation (unless it has been actively refused). For myself, I have registered as a donor (here) to ensure than nobody is in any doubt about my wishes. (You can alternatively register NOT to donate on the same site.) As with advance decisions to refuse treatment, which give people clarity about your wishes for medical treatment at the end of life, so too with organ donation. I cannot emphasise strongly enough the importance of making your wishes clear in advance. Nageena Khalique QC said it best: ‘There cannot be any clearer indication of TW’s wishes and feelings in relation to organ donation than the form he completed himself’.

Final Reflections

As an academic, I can summarise the ethical and legal lessons from this case. As a human being, I am speechless at having witnessed the remarkable compassion, care and solidarity shown by those involved, in pursuit of their collective goal of acting in TW’s best interests.

Earlier this week, the approved judgment was published. Reading it, the first thought that came to mind was how much it differed from my experience of observing the hearing. Of course, the facts and the law were the same. But, if I had not been in the (virtual) courtroom, watching the case unfold in real time, I would not have had so much appreciation for the sensitive approach that was used in reaching this decision and the fact that all possible options were fully explored. Nor would I be aware of all the additional detail that is gained from hearing medical experts and family members address the court.

Like most academics, I have my critical thinking cap on when I read published judgments. I tend to react with a cry of ‘I don’t agree with this at all!’ and set out a plan to write a case commentary. Yet, my take-home message from observing this hearing is to perhaps follow a more cautious approach in future, and to bear in mind that there are likely to be details that I might not be privy to and aspects of human relationships and ethical complexity that can’t be summarised in a written judgment.

Bonnie Venter is a PhD candidate and Senior Associate Teacher in Medical Law at the University of Bristol Law School. Her PhD research is based on a legal and regulatory evaluation of the living organ donation pathway, with a specific focus on the psychosocial assessment of the living organ and tissue donor. She tweets @TheOrganOgress

[1] At the beginning of the hearing, it seemed that family members were united in believing that TW should continue to receive life-sustaining treatment, and that Ian Brownhill, though formally instructed by TW’s brother, thus represented them all. As TW’s wife said, “we’re all in this together”. As the hearing unfolded it became clear that TW’s daughters (who were hearing the medical evidence for the first time) took a different position from his brother, and so found themselves unrepresented. So too did TW’s wife, at the end of the hearing when she wanted to appeal the judgment but TW’s brother (who was instructing Ian Brownhill) did not.

[2] Note: There was absolutely no suggestion or any connection whatsoever between the Trust application for treatment withdrawal and the fact that TW was a registered organ donor. Prof D specifically said in his statement that unfortunately, TW could not be a donor in ‘these circumstances’ and also emphasised that ‘he does not wish to present this [organ donor card] from this point of view’. This should not need saying, but it has been pointed out to me that another case in the COP this year in which the Trust sought to (and did) withdraw life-sustaining treatment attracted negative publicity with claims of NHS organ procurement (with absolutely no evidence whatsoever!).

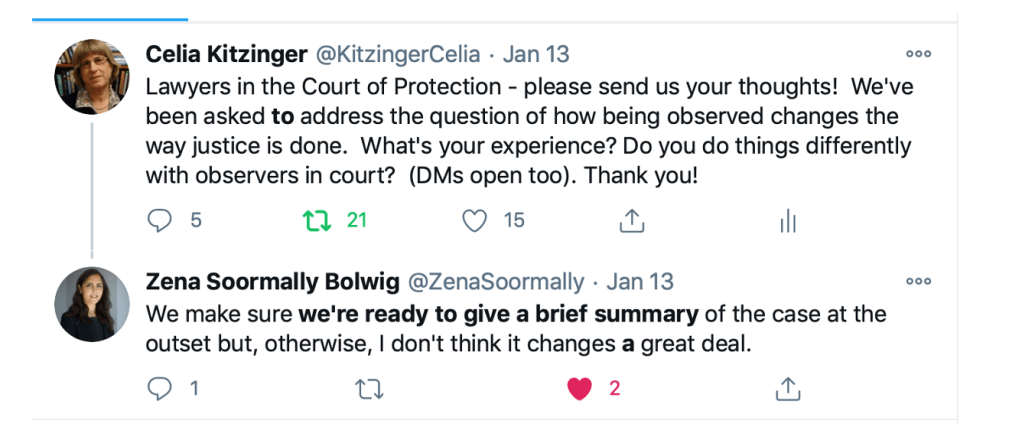

Photo by Mitsuo Komoriya on Unsplash