By Claire Martin, 17 March 2024

There has been a series of hearings concerning Laura Wareham. I observed a previous hearing in June 2023, and blogged about it here. At that hearing, the Health Board was seeking a 12-week cessation of all contact between Laura and her parents.

In this blog, I have chosen to write about relationships between patients, families and systems of care. What I witnessed in the hearings that I observed I found very alarming. What I have written is based on what I have learned about the relationships between Laura Wareham and the teams who look after her (as well as her parents who are central to her life). It Is also based on what I have learned in my own professional role as a psychologist about relationships between care teams and those they are caring for.

I observed most of the final hearing concerning Laura’s capacity on 19th and 21st February 2024. I was sad to miss Laura speaking for herself when she addressed the court on 20th February and I understand that her concerns were clearly and articulately expressed, leading at least one observer to believe that she clearly demonstrated capacity in all domains – a view that she subsequently revised when she considered the law underpinning capacity assessments (see “An articulate and intelligent P is found to lack capacity: Laura Wareham in court”).

In his judgment at the end of the hearing, Deputy High Court Judge McKendrick KC found that Laura lacks litigation capacity, capacity to decide her care and support, where she lives and with whom she has contact. There is to be a further assessment of capacity to decide on use of social media.

I have not met Laura or seen the capacity assessments and cannot know whether they are correct. Laura and her parents oppose these conclusions, arguing that Laura has capacity for all these decisions. Dr Camden-Smith, expert witness psychiatrist, was adamant in her conclusions regarding lack of capacity for Laura on all these matters, citing Laura’s autism as the “impairment of the mind or brain” underpinning the current lack of capacity. She also, however, said that Laura might regain capacity for such decisions in future. The expert chosen by the parents, Dr Eccles, was also – after cross-examination – unable to state that Laura had capacity to make any of the relevant decisions for herself.

Whether the declarations on capacity are correct or not (as public observers we do not have access to all court documents and evidence, so are not in a position of full knowledge about any case), the restrictions and removal of agency for Laura are extensive.

Because there’s a determination that she lacks litigation capacity, she cannot instruct a legal team herself – instead being represented by the Official Solicitor, who is instructed by a solicitor who Laura has apparently fallen out with and won’t communicate with. Key lines of communication with Laura are, seemingly, beset with difficulty: the health care system and legal representatives have found themselves unable successfully to navigate relationships with Laura and her family.

Laura remains in a care setting that she does not like and has no choice about and objected to moving to, and she opposes any ongoing involvement in her care from the current Health Board. She is restricted in terms of her contact with her parents, with whom she lived for 33 years before being admitted into hospital in 2021. She is judged to lack capacity in relation to most aspects of health care decisions (except I believe for decisions about catheterisation).

In relation to her medical needs in particular, Laura is said to have developed ‘erroneous beliefs’, shared and ‘reinforced’ by her parents, which have led to harm (in the form of unnecessary treatments). Dr Camden-Smith’s evidence (quoted from the Position Statement for the Health Board) stated: “The extraordinary and harmful care previously provided to Ms Wareham cannot be underestimated; I cannot comprehend how a situation arose in which Ms Wareham was receiving the medical interventions that she was without any clear medical evidence of need or benefit; however it did arise and the risk remains that this pattern will be repeated, particularly if the Warehams move to a new area.”

I don’t know how Laura came to receive such ‘extraordinary and harmful care’ from previous medical teams. I do know that patients and their families cannot compel medical teams to offer treatment that they do not think is clinically appropriate, and I am interested in where the responsibility is located, in relation to Laura having received ‘medical interventions … without … need or benefit’. I found the statement above curious – it seems to be suggesting that Laura and her parents are solely responsible for the ‘harmful’ medical treatment that Laura has received. As if the treating team(s) are not able to make autonomous clinical decisions. One could argue that another potential source (albeit not current) reinforcing beliefs about medical needs (whatever those may be) could be that previous medical practitioners have given treatment for conditions that are now rebranded under the heading of ‘erroneous beliefs’. Perhaps it is not easy for Laura to understand why she is expected to trust some medical practitioners (her current team) and not others (her previous team(s)).

In McKendrick J’s judgment of 5th March 2024, he states (at §20): “Whilst challenged in these proceedings, it is important to record the views of treating clinicians is as follows (taken from the October 2023 evidence): “Dr and Mrs Wareham’s …[…] behaviours are potentially causing Laura to be confused or very anxious about her state of health to the extent that she appears to have developed a false self-view of being sick and this is now driving her own erroneous beliefs of her own sickness along with the role of unhelpful own peer groups on social media which can potentially encourage each other to remain ill.” […] There is a complete agreement on the continuing need for de-medicalization including reducing /stopping unnecessary medication (which has already been done with full oversight of the MDT) and offering graded physical rehabilitation.””

So the need for de-medicalization is a ‘fact’, established in a previous judgment (with which Laura’s parents strongly disagree).

It was clear from the hearings I observed that relationships between Laura and her parents on the one hand, and clinical teams and the Official Solicitor on the other, are strained and fractious. Fractured relationships can lead to attrition and blame. Of course, this can be both ways – though power is not on a level playing field when it comes to capacity assessment, health and social care systems. Listening to this statement (above, by Dr Camden-Smith) read out in court alerted me to listen for other suggestions that errors and blame might solely be located in Laura and/or her parents, rather than anywhere else within the system of care, or in the relationships between them all.

Where is responsibility located?

Rigid and Agitated

Dr Camden-Smith referred, in her oral evidence to the court, to Laura being ‘highly focused’ on matters that others do not consider relevant to the court’s decision. Dr Camden-Smith said:

“The primary difficulty is [that] Laura focuses on details and matters that are not germane to the matters at hand … she’s highly focused on small areas such as the Human Rights Act, genocide and the Montreal convention …. She remains as rigid and agitated by that as she has been all along.”

In cross-examination from Abid Mahmood (counsel acting for Laura’s parents) Dr Camden-Smith confirmed “I recognise her human rights might be being impinged, but that’s not the remit of this court. We are dealing solely with capacity … human rights [might be] breached, but they are qualified rights”.

It feels as if Laura’s concern with her human rights is being seen as a ‘small area’ and she is cast as ‘rigid’ for determinedly referring to these concerns, even though there is confirmation that her Human Rights are being breached. I understand that the expert witness is not saying that Laura should be less ‘rigid’ and is stating a fact as she has assessed it. However, I wonder why Laura repeatedly brings these issues up? What is happening that she persists in the face of opposition to consider them?

Abid Mahmood later addressed this issue in his submissions to the court:

“This is a factually complicated case. May I touch on contact briefly. The context is that Laura was living at home for 33 years with her parents, now the situation is extremely limited for options for face-to-face contact and remote [contact] 2-3 times a week. The undisputed evidence is it breaks down due to tech issues. […] Laura sees her parents before extensively, because she lives with them. Then very very difficult limited contact. It is frustrating for Laura and her parents. She can’t access social media, she can’t engage with the staff. So that’s the context and then ‘well she keeps going on about human rights’. […]. Laura’s ‘fixation’ in respect of Human Rights. Dr Camden-Smith was not providing her expert evidence in respect of this – Laura was correct when she has said that her Article 8 right to family life and Article 3 right to live free from degrading treatment and Article 5 right to liberty are correct. This is a vivid example where [the] court can see that Laura is seeking to inform and educate the court – and others – saying to care workers ‘I have Article 3 rights’ is not going to be listened to”. [Counsel’s emphasis]

Judge: I am empathetic to that condition… Dr Camden-Smith said that the Human Rights Act doesn’t fall within this jurisdiction, she’s probably wrong in law […]”

My understanding of these exchanges is that Dr Camden-Smith was assessing and reporting on capacity for specific decisions and did not think that Laura’s Human Rights were pertinent to her task. Laura, on the other hand, prioritises these concerns. That fact, I think, is seen as Laura’s problem by the Health Board and expert witness Dr Camden-Smith.

Erroneous Beliefs and Alienating Staff

McKendrick J was asked to consider restricting contact with people said to reinforce Laura’s ‘erroneous beliefs’ about her medical needs, with the aim of facilitating her cooperation with rehabilitation and ‘demedicalisation’. All three counsel addressed this issue: who is said to be harmful and how extensive should be the restrictions.

Eloise Power (Health Board): I am being instructed to put forward that declarations should be made about contact with others, not merely the parents. […] One possibility is to make declarations to restrict contact with the parents and others who reinforce the erroneous beliefs.

The Health Board was asking the judge to declare that the care team could restrict Laura’s contact with anyone (including internet groups ‘that may reinforce the damaging thinking’) that they deemed to be ‘reinforcing erroneous beliefs’. I was heartened to hear the following:

Judge: Who is policing this idea of others who are reinforcing these erroneous beliefs? Imagine Aunty S arriving and staff being told ‘Aunty S reinforces erroneous beliefs.’ I might be persuaded that an application is needed to be made.

The judge here was saying ‘No’ to the blanket authorisation, seemingly requested by the Health Board, to restrict contact with people other than Laura’s parents. He had earlier also said “I am not going to be signing a blank cheque” in relation to restricting Laura contacting bodies such as the Food Standards Agency, or the Health Service Ombudsman or even 999.

Ian Brownhill, for the Official Solicitor, said: “The OS would oppose a general and broad declaration that Laura lacks capacity to decide contact with others. [There is] not the evidence. It seems the Health Board already has potential categories in mind. They should say [what these are] and … [they] should be tested. […] Turning finally to the broader issue of Laura’s ability to contact external agencies – I have two submissions – firstly we would submit that there’s a difference between Laura contacting a super-specialist in a particular area, to contacting 999 or the Food Standards Agency or the ombudsman. [There is] no authority, as far as I am aware, where the court has been asked to make declarations regarding the Food Standards Agency, the Human Rights Commission etc. There have been previous attempts to encourage the court to make declarations that someone does not have capacity to contact 999 – but no reported judgments. The OS has felt concern that someone should be prevented from calling 999 and where P has had a wish to contact people who have a statutory responsibility for safeguarding, for example the ombudsman, FSA etc. [The OS has] significant discomfort if the court is being asked about that”. [counsel’s emphasis]

Judge: “My preliminary view is to agree with this counsel”.

Eloise Power said that the Health Board had not sought further restriction on contact with others or on social media (this seemed to be contrary to the previous statement from Ms Power that ‘I am being instructed to put forward that declarations should be made about contact with others, not merely the parents’) – however, there was clear concern on the part of the Health Board about these issues and a suggestion from Eloise Power that there would be a Health Board ‘assessment and best interests decision’ in relation to these concerns.

Rather unusually for a barrister (they are often poker-faced) Ian Brownhill had what he described as a “visceral reaction” to this as Ms Power was speaking (a sharp intake of breath) and raised a concern about this: “My submission regarding Ms Power …. the Health Board ought not to be holding Best Interests meetings when My Lord is making Best Interests decisions.”

Judge: Laura is a P in the Court of Protection, so if Best Interests decisions are being made they ought to be made by a judge.

Judge McKendrick made it clear to the Health Board that ‘between now and the next hearing’: “Laura needs something to do. […] if she wants to while away the hours on Pinterest, that can be subject to light touch supervision”.

Could it be that, in the context of fractured relationships, an over-reach of power and control is sought in the name of ‘protection’? Munby J famously said, “What good is making someone safer if it merely makes them miserable?”. The longer quote from that judgment suggests that ‘Physical health and safety can sometimes be bought at too high a price in happiness and emotional welfare’. As far as I know, the ‘harm’ that Laura’s parents are said to pose to her is from seeking, widely and repeatedly, specialist treatment for Laura, which is said (later, by different treating teams) to have led to treatment that has been deemed ‘harmful’ and of ‘no benefit’. There isn’t evidence or established fact that Laura’s parents are aiming to harm her health, but that they have different views to current treating clinicians about her medical diagnoses and needs. And that those differing beliefs influence Laura’s thinking about her needs.

The judgment states that: “Dr Camden-Smith carefully considers whether Laura’s presentation meets the diagnosis of Factitious Disorder Imposed On Another (ICD-11 6D51) but does not find “clear and unequivocal” evidence to support this although she is of the opinion that the parents “contribute materially and substantially to Ms Wareham’s illness behaviour and help-seeking behaviour…..[and] often obsessively seek out medical professionals who reinforce their own (erroneous) illness beliefs.”

I don’t think the potential impact of losing their other daughter, quite recently – a daughter who also had Ehlos Danlos (though she died from cancer) – can be underestimated. As parents, they must be terrified of losing Laura too. Often, people’s behaviour is cast as extreme. Another perspective could be that – faced with life and death situations – people’s behaviour can be normal in abnormal circumstances.

A judgment in 2021 by Mr Justice Hayden is relevant here. In this judgment, Hayden J reflects on the ‘regular’ situations in the Family Court and the Court of Protection, where parents have “become drawn into high octane conflict with the raft of professionals who seek to support their child’s care”. He later refers to parents of adult children similarly (“I would add that a similar dynamic and frequently for the same reasons identified here, arises in the Court of Protection when dealing with incapacitated adults.”). Hayden J commented on the expert witness (Dr Hellin) evidence in that case, in relation to the parents’ response to their child’s conditions and care (‘M’ in the quote is the mother):

“As Dr Hellin points out in clear and unambiguous terms, this anxiety is “rational” and based in the “cumulative reality of life-threatening medical events in [W’s] life and the uncertainty of his condition and prognosis”. M’s response to the very challenging circumstances she faces are said to be “normal” and Dr Hellin would expect “a similar response in even the most psychologically robust person”.

The judgment in that case stepped back and took a systemic view in order to understand the ‘dynamic processes’ that were at play: “Already it is clear to me, before any work is undertaken, that this exposition of the dynamic has helped both the care workers and the parents better to understand the challenges that each face. […] Perspectives had become polarised and difficult to placate. Dr Hellin’s proposals are predicated on promoting mutual understanding and diminishing mutual blame.”

I do wonder whether an intervention of this kind is needed for the whole system of care around Laura. It is clear that relationships between Laura and her parents, and those looking after her on a day-to-day basis, are very polarised indeed. The Health Board has reached a position where it seems to want to police almost every interaction that Laura has, whether in-person, online or via email or letter. The Official Solicitor expressed ‘significant discomfort’ at that suggestion.

On the one hand, the health and care system seems to feel attacked and beleaguered in their dealings with Laura and her parents, to the extent that previous health teams have (according to Dr Camden-Smith) acceded to providing ‘harmful’ medical treatments. On the other hand, Laura and her parents are claiming that Laura’s health and care needs are not appropriately met and that her human rights are being breached. One word in Dr Camden-Smith’s evidence (from the Health Board Position Statement, kindly provided by Eloise Power) jumped out at me:

“She fails to realise that her rigid insistence on her chosen issues alienates those caring for her and makes it impossible for her solicitor to elicit any coherent instructions regarding the matter at hand. Ms Wareham remains convinced that her viewpoint and interpretation of the law is the only correct one and that those who aren’t able to convince her otherwise are wrong.” [my emphasis]

Alienation

The statement above about Laura’s “rigid insistence on her chosen issues” is, basically, saying that because Laura won’t stop talking about things that her carers don’t want to hear about, she ‘alienates’ them. Locus of responsibility, I would suggest, is placed in Laura here. Looked at another way, perhaps Laura’s care team won’t stop talking about things that Laura doesn’t want to hear about, and they ‘alienate’ her! Or perhaps, this is a shared dynamic that needs stepping back from, “better to understand the challenges that each face” (Hayden J. above).

Learning about Laura’s situation and the responses of the health system around her has caused me to reflect on how systems of care can, often unwittingly, develop unhealthy and even harmful relationships with those they are there to care for. Hayden J’s judgment above is referring to this dynamic. Anyone on the receiving end of care is (by the very nature of the ‘caring-to-cared for’ relationship) in a less powerful position than those in the ‘caring’ role (although that might not always feel the case to those in the system). Iatrogenic harm is defined as “any injury or illness that occurs as a result of medical care”. This can be thought of more widely than ‘medical’ care and physical illness in their narrowest sense. In physical and mental health care this has been written about extensively [for example here, here and here; and in relation to specific types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome here and here].

There is a concept in mental health care called Malignant Alienation., although it doesn’t solely apply to mental health. It has been used broadly to understand organisational dynamics of care.

It is hard for professionals working with patients and their relatives and supporters when there is dispute and acrimony. It is (perhaps) harder for patients and relatives, in the less powerful ‘cared-for’ role, to work with professionals when there is dispute and acrimony. It can be common for both sides to blame each other. Whatever the rights and wrongs and who did what when, Laura is a person who is not, actually, in a powerful position. She has significant care needs and she is assessed (by the expert witnesses) as having “a likely significant mismatch between her verbal proficiency and her processing skills”. She has been prevented from returning to her home with her parents, partly due to the harm they are said to pose by fuelling her ‘erroneous beliefs’ but also because (if this were an option the court would consider) the Local Authority says this is not an option due to the excessive cost of a home-based care package.

These are difficult circumstances and I have no doubt that carers find it difficult looking after Laura. I heard though, at times, these relational problems being firmly located in Laura (and her parents). I give two examples below, one from the expert witness Dr Camden-Smith and one from Eloise Power, counsel for the Health Board.

Dr Camden-Smith (from Position Statement): “… it remains my opinion that she is unable to consider all the information holistically and in the round, choosing what to prioritise and how to ‘pick her battles. She remains convinced of the superiority of her understanding of the law and frustrated at the perceived refusal of her solicitor to advance the arguments she would like to have advanced, despite these often not being relevant to the current proceedings. Attempts to discuss matters with her are generally overwhelmed by her detailed complaints about how her rights are being breached and the ways in which she is subject to torture and genocide. She may well have claims under the Equality Act and Human Rights Act, however this is not the forum to address those claims. Ms Wareham is incapable of holding more than one option in her mind so as to be able to compare them and project forwards hypothetically.”

The expert witness report from Dr Camden-Smith states “This is due to her autism, exacerbated by her pathological beliefs about her illness“.

Surely, it would be even more incumbent on services, then, to find ways of improving communication and acknowledging distress. I am sure that the services around Laura have tried their best to do this: however, whatever care plans, communication and strategies have been put in place, they don’t seem to have worked.

Eloise Power: “In relation to matters of concern fed to your Lordship by Laura herself….”. The phrase ‘fed to’ – in place of a more neutral rendition such as “reported to” or “raised with” is interesting. It implies doubt on the legitimacy of Laura’s concerns (which were about not having access to a Bible, to her iPad, to personal care from female carers, not having her bed changed often enough, being prevented from contacting the Office for the Public Guardian and an issue with lighting and noise in the care setting). It has resonances with the phrase “fed me a line” (which Merriam- Webster defines as: to tell (someone) a story or an explanation that is not true). It’s likely the Health Board’s experience of these issues is different to Laura’s, but I wonder whether that phrase “fed to” would be used, for example, in relation to an expert witness’s evidence.

Eloise Power made it clear that the Health Board’s position is very different to that of Laura:

Judge: She is extremely close to her parents. I have already authorised a relaxation of these to include face-to-face with her parents – I am not aware of particular issues ……

Eloise Power: Alas it goes beyond that My Lord.

I found it interesting that the judge is relaxing the restrictions on contact with Laura’s parents – yet the Health Board continues to paint a different relational picture. It did make me wonder whether, organisationally, the Health Board is also finding itself unable to be flexible in how it views and relates to Laura and her parents. If there is evidence that restrictions should not be relaxed, I assume the Health Board would have submitted it.

Groves (1978) talks about the following:

There is a long tradition, in psychoanalytic and psychological thinking, of exploring our own feelings and responses towards those we care for. Analysts call it ‘countertransference’. This can be uncomfortable and difficult for clinicians and carers, and so it can feel much more attractive to avoid this area and locate any difficulties in patients. It can be much more bearable and acceptable, in cultures of care, to ‘project’ our bad feelings into the ‘difficult’ (less powerful) patient. However, that is much more likely to lead to attrition and entrenched positions. Is this a possibility in Laura’s case?

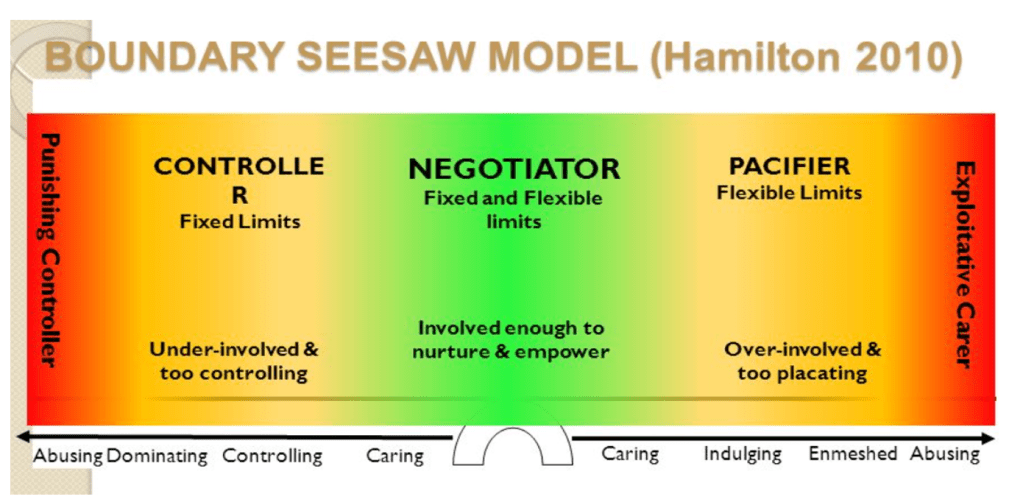

In a book called Using Time Not Doing Time, Hamilton suggested a model to describe ‘a continuum of professional behaviour’ (this model was developed in forensic settings and has been used much more widely across health and social care):

The ‘controller’ end of the seesaw is often described as the ‘security guard’, a role that is concerned with rules and tasks and where, if a patient challenges those boundaries, the immediate response is often to tighten the boundaries. The patient on the receiving end often feels controlled, judged, emotionally neglected and vulnerable. And they then can become (in the eyes of the professionals) ‘challenging’. But it is a reciprocal relationship – both parties contribute and (usually) one party has a lot more power and potential support to step back and find another way.

At the end of the hearing, communicating his judgment, McKendrick J said: “I told Laura the decision – my observation was that she accepted the decision. It seems to me clear from my judicial visit that Laura remains, notwithstanding the hard work that has taken place – a vulnerable and scared woman. She told me ‘I am scared’ … ‘I really need a legal team with which I feel safe and secure’. She does not have access to the amount and type of food she wants, her bed is not changed with enough frequency, she can’t speak to her aunt, she can’t contact external safeguarding agencies to help her feel safe. […] She had a download of the Bible but that has been deleted. She wants […] to have food delivered and wants to use Pinterest and hasn’t [been allowed to]. I would like the parties to address those issues Laura has raised. [They are] small matters to professionals, but small matters that can have a significant ability to reduce the anxiety and fear Laura feels in her situation. If [there is] meaningful discussion between parties now, Laura’s feeling of being scared may be ameliorated. I want the order to be given to Laura tomorrow so she has some agency. I can’t understand why she can’t have Deliveroo – she has money. I am not putting forward a position. The point is this: she is in a vulnerable position, she is scared and vulnerable. My job is to protect her – I don’t want to get into a ding-dong about this is wrong that’s wrong. I understand that there is a dispute […] but if it’s Laura’s misconceptions, if that’s what they are, [they] are making her distressed”. [My emphasis]

The Position Statement of the Official Solicitor (kindly shared by Ian Brownhill) reinforces this view, as well as advocating for fewer restrictions:

“Laura Wareham’s access to the internet and other restrictive practices must be considered with a view to reducing those restrictions.

Importantly, work needs to start now to build Laura Wareham’s relationship with her treating clinicians and to support her parents who are undoubtedly an important part of her life.”

I thought that Judge McKendrick articulated the key relational point: Laura is ‘scared and vulnerable’, no matter the intricacies of the ‘ding dong’. As the judge said, some issues might be “small matters to professionals, but small matters that can have a significant ability to reduce the anxiety and fear Laura feels in her situation”. I would add to that: perhaps these small matters might improve Laura’s chances of being deemed capacitous to make certain decisions, or at the very least to improve relationships with the system around her. Importantly, Ian Brownhill’s position statement submitted, “work needs to start now … build[ing] relationship[s]”. And this is the responsibility of those caring for Laura to take the lead, despite feeling alienated.

I really hope that by the next hearing in April 2024 some progress will have been made towards some agreed best interests’ decisions, for all concerned.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core group of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published several blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She tweets @DocCMartin

The DSM V doesn’t even describe autism like this- it mentions impairments yes (unfortunately) but not of the mind/brain!

Kerry

>

LikeLike