By Jenny Kitzinger, 4th December 2024

The Court of Appeal hearing I observed on the 26th November 2024 concerned an application for permission to appeal a Court of Protection judgment.

I’d watched the original Court of Protection hearing (COP 20002405) in early November and blogged about it (“Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: Faith and Science”). The judgment, handed down on 11th November – so just two weeks before the Court of Appeal hearing – authorised withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment from ‘XY’, a woman in a Prolonged Disorder of Consciousness.

In the course of the Court of Protection hearing, clinicians gave clear and unanimous evidence about XY’s catastrophic brain injuries, her lack of awareness and why there was no potential for any recovery: and they explained why they thought it was in her best interests for life-sustaining treatment to stop. Her family and friends gave clear and consistent evidence about why they believed that XY was aware of their presence, why they thought her condition might improve and why they thought life-sustaining treatment should continue – including, centrally, because that is what XY would have chosen for herself given her strong values and religious faith.

The subsequent judgment, by Mrs Justice Arbuthnot, authorised the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment on the basis that, due to severe and extensive brain damage, continuing treatment was not in XY’s best interests.

The application for permission to appeal was made by XY’s daughter. A stay had been placed on the withdrawal of treatment until the application could be heard.

I was particularly interested in how the appeal might be handled because I also have personal experience of representing a family member’s values and beliefs in relation to treatment decisions about her – and, like the family in this case, I was over-ruled. I return to this element of the hearing in my personal reflections at the end of the blog.

The parties, representatives and judges in the Court of Appeal

The daughter of XY was no longer represented by the team (funded by legal aid) that had acted for her in the Court of Protection. Instead, she had brought the application as a litigant in person. Shortly before the hearing, she’d gained pro bono (i.e. free) representation from Mr George Thomas (who was thanked by the judge for stepping in at very short notice).

The other parties in the case were represented by the same barristers who had acted in the Court of Protection: King’s College Hospital NHS foundation Trust, where XY was receiving treatment, was represented by Mr Michael Mylonas KC. The patient herself was represented (via her litigation friend, the Official Solicitor) by Ms Sophia Roper KC.

The judges in the Court of Appeal were Lord Justice Baker and Lord Justice Phillips.

Access and transparency

Observing a Court of Appeal [CoA] hearing is very straightforward compared to the Court of Protection if – as was the case for this one – it is live-streamed.

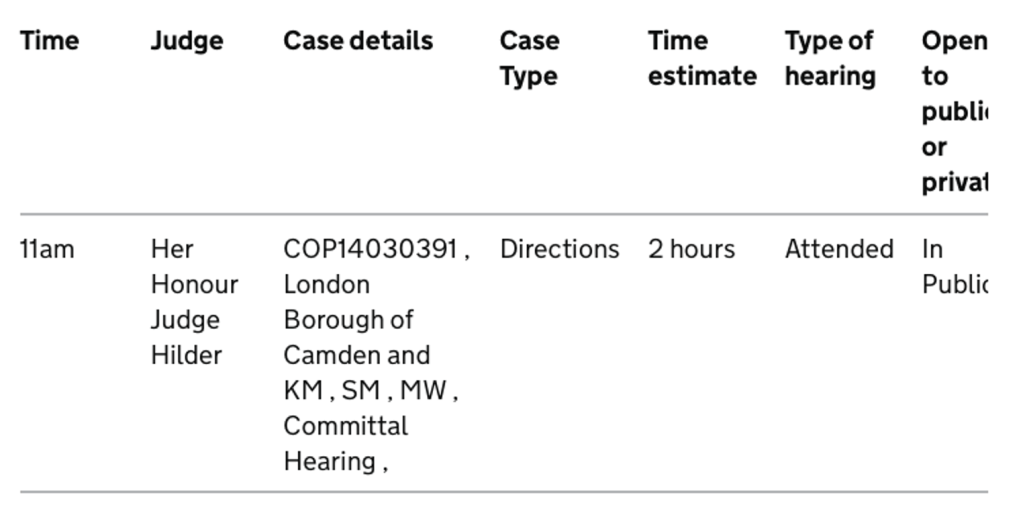

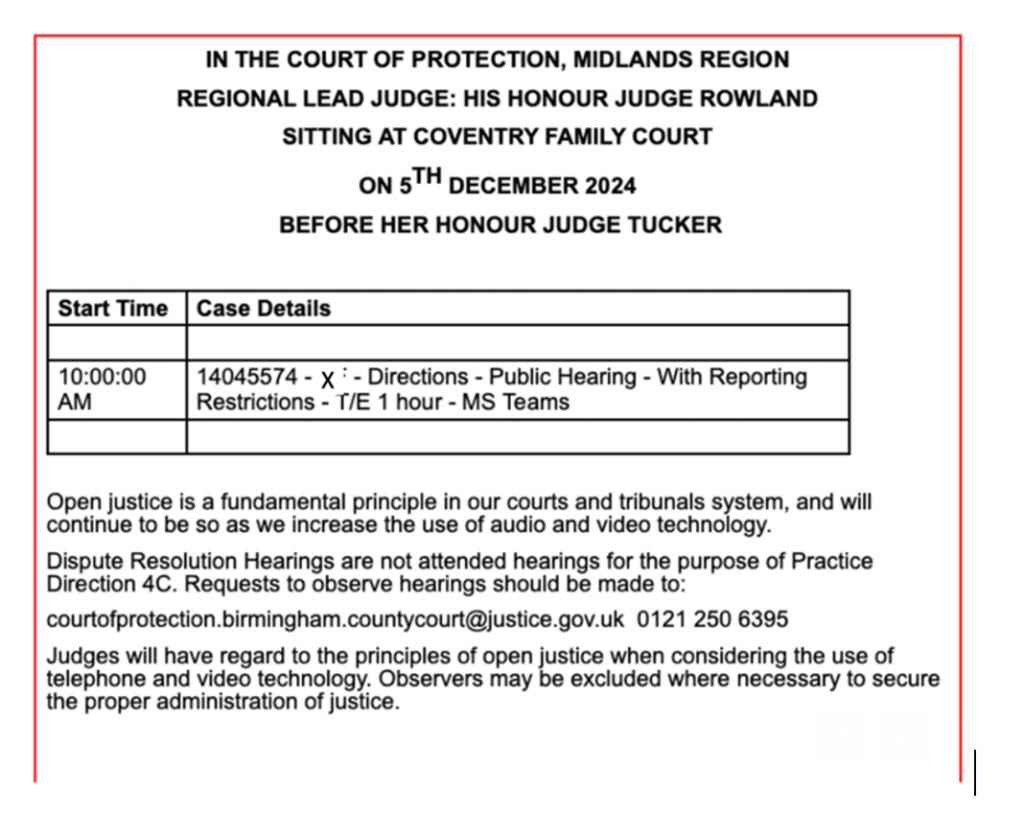

Many Court of Appeal hearings are clearly listed several days in advance, live streamed and recorded (see https://www.judiciary.uk/the-court-of-appeal-civil-division-live-streaming-of-court-hearings/). This means there is no need to email to ask for a link based on listings that are only available the night before and then anxiously await the link being sent. Also, you don’t have frantically to try to capture every word from a live hearing, you can concentrate on following the arguments, safe in the knowledge you can always go back to replay sections later to pick up certain details or quotes.

The main problem for transparency in relation to this case was that I had not yet seen the judgment. It had been handed down on 11th November 2024 but was not published, and not available to the public, by the time of the appeal court hearing. I understand that this was due to workload pressures on Mrs Justice Arbuthnot, who made the original COP judgment. Whatever the reason, it is challenging to follow arguments about why a judgment is (or isn’t) wrong without having read that judgment or being able to refer to it during the hearing.

The barristers had clearly made efforts to see if an anonymised version of the judgment might be available before the appeal hearing and Lord Justice Baker checked at the start of the hearing to ensure that redacted versions of the skeleton arguments were available to observers (thanks to Celia Kitzinger for asking for these and the barristers for making sure these were redacted and shared under very tight time pressures). The judgment from the Court of Protection was also published the day following the Court of Appeal hearing, so I have been able to read it prior to writing this blog.

The hearing

To be successful on appeal, an applicant needs to demonstrate that the original decision was wrong or unjust because of a serious procedural error or an error in applying or interpreting the law. Permission to appeal will only be granted if there is a good chance of the appeal succeeding, or there is some other compelling reason to hear the appeal.

The hearing about this application for permission to appeal lasted almost 3 hours. You can view the video-recording of the whole appeal on the Court of Appeal video archive page. Some parts of it felt like a re-presentation of some of the arguments presented in the Court of Protection – so even if that is your main interest, rather than the workings of the Court of Appeal, I’d recommend listening to the recording for that reason alone.

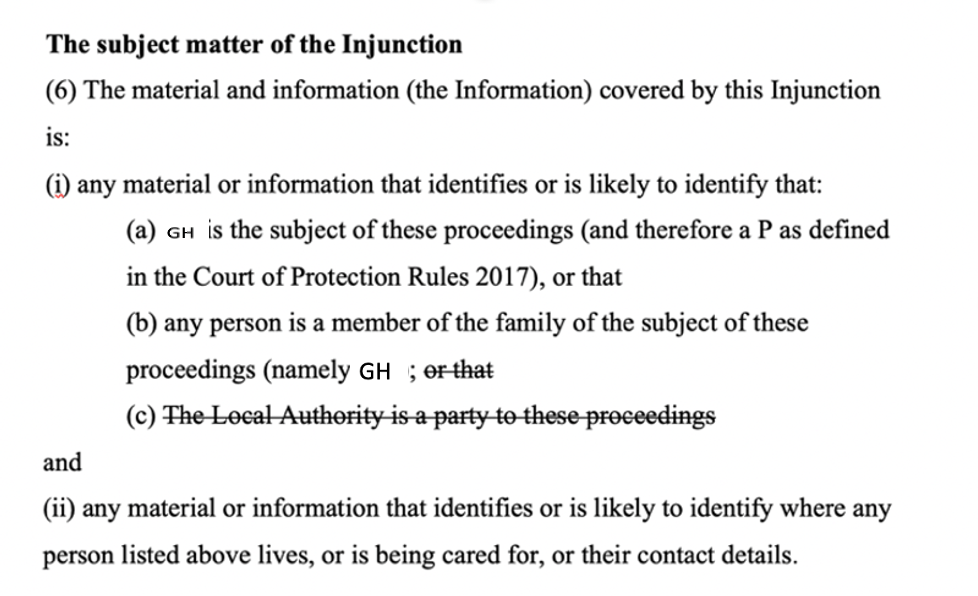

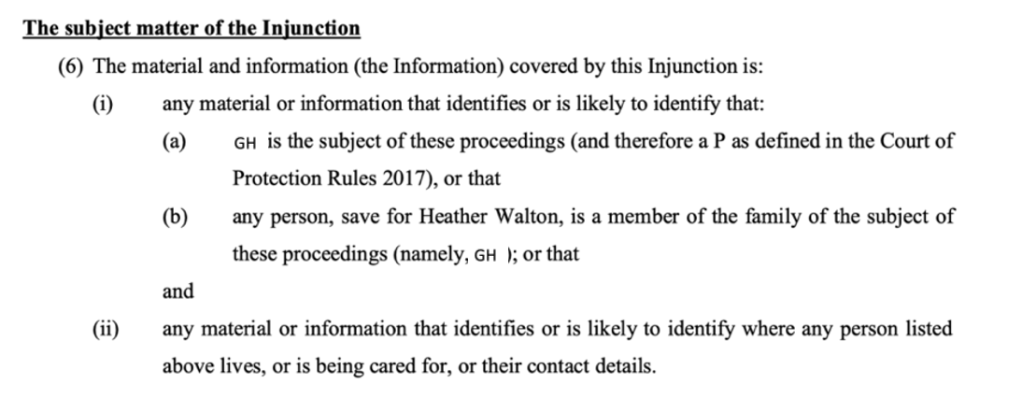

Lord Justice Baker opened the hearing by asking for clarity about who was in court and welcoming the family members present (XY’s daughter, grandson and aunt – mostly seated back left of the court and off-screen). He explained that the Transparency Order from the Court of Protection does not apply in the Court of Appeal so new reporting restrictions would be ordered and he also (with apologies to the family for it sounding impersonal) clarified that the woman at the centre of this case would be referred to as XY for the purposes of this hearing. ‘XY’, it was made clear, was not just an anonymous set of initials – she was a unique individual with her own values and faith, a much-loved mother and grandmother, a popular member of her local community and with a large extended family in Jamaica.

The daughter’s position

Counsel on behalf of XY’s daughter (the applicant), spoke first, and his submission to the court took up the majority of time (almost two thirds of the hearing). He started by outlining the grounds for permission to appeal and it soon became clear that XY’s daughter (originally acting as litigant in person, i.e. without representation) had submitted a skeleton argument broader in its scope than the issues Mr Thomas wanted to focus on as grounds of appeal. For example, the daughter’s skeleton argument had apparently argued that there’d been procedural flaws in the CoP hearing because no independent neurological opinion was selected by, or with the satisfaction of, the appellant or her family. In fact, a neuro-critical care specialist, Dr Bell, had been commissioned by the daughter’s solicitors, but had arrived at the same conclusion as all the other clinical experts about XY’s level of consciousness, and took the same position as they did that it was in her best interests to have life-sustaining treatment stopped.

Once Mr Thomas had become involved, he had submitted an additional supplementary skeleton argument focusing on just two grounds of appeal relating to material errors in how the judge made her best interests assessment. First, the judge was not entitled to conclude that XY was unresponsive, given the evidence of friends and family that she was responding to their presence. Second, the judge failed to give sufficient weight to the significant amount of undisputed evidence from friends and family that XY would not want clinically assisted nutrition and hydration to be withdrawn. Although Mr Thomas touched on some other points (such as the issue of the independent expert), it was these two grounds of appeal that formed the basis of his submissions – and I use them to structure my summary of the submissions and my subsequent discussion.

Family evidence of responsiveness: In her judgment Mrs Justice Arbuthnot found as follows:

107 .”I find that XY does not track with her eyes nor does she respond to voices or commands to squeeze their hands. I can understand how a family who wish that this very much loved family member should recover are misinterpreting what they see. They see responses to their care rather than the reflexes controlled by the brain stem that the medical specialists identify. That is not to say that at some level XY is getting comfort from their touch, but it is not a conscious sensation.”

and

117. Her family and friends visit her daily but she gets no enjoyment from their frequent visits. The evidence shows she does not hear her family when they visit or even knows they are there.

Representing XY’s daughter, Mr Thomas took issue with such statements, arguing that the judge was wrong to dismiss the evidence of responsiveness presented by the family. He highlighted how family and friends visited XY often and sat with her for long periods of time; they had a long-term intimacy with XY that the nurses lacked and, unlike busy hospital staff, they had time to talk to, and pray with, her. He pointed out that six different witnesses had submitted written statements reporting having directly witnessed XY’s responses. He argued that, had the judge assessed the evidence in a properly balanced way, a different best interests decision would have been reached.

Consideration of what XY would have wanted: In her judgment, Mrs Justice Arbuthnot found as follows in relation to what XY would have wanted:

111. XY has never stated her views about clinically assisted nutrition and hydration or on sustaining her life artificially in the circumstances where she is totally dependent on others and cannot function in any of the ways she used to, where she is not aware even that her family is visiting her.

112. Despite not being in the best of health, she never had that sort of conversation with her daughter (or anyone else). We do not know how she would feel in the current situation that she finds herself in. We do not know what she would feel about the enormous pressure being placed on her family and friends of this very long drawn out, tragic situation.

113. She worked in a hospital and is likely to have come across death and serious illness there but we do not know how she would feel about the continued treatment when the specialists and experts say it is futile. She was a woman of faith, but I question whether this loving mother and grandmother would have wanted the burden of the treatment to continue. She may have wanted her family to be relieved of the long drawn out pressure they are under.

114. I appreciate the family know her best, particularly XZ [her daughter], but I am not convinced that this matriarch who always put her family first would have wanted them to continue going through what they have been.

Counsel for the daughter was critical of Mrs Justice Arbuthnot’s summary concerning XY’s views. It was, he said, wrong to say “We do not know how she would feel in the current situation” – there was a great deal of strong evidence that XY would, in fact, have wanted life-sustaining treatment to be continued. He quoted a statement from XY’s daughter that given XY had ‘died and been brought back to life’ (i.e. the one-hour plus ‘down time’ while paramedics tried to resuscitate her), her mother would believe God did this for a reason and she was here for a purpose.

He also highlighted that her religious beliefs were a key part of who XY was as a person and pointed to the importance of upholding her rights under Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights – which guarantees the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. XY believed in the sanctity of life and in miracles and, crucially, that it is for God rather than medical staff to determine when someone’s life should come to an end.

He referenced case law supporting the ‘magnetic importance’ of P’s wishes where these can be determined with a high degree of certainty (whether those wishes are to have treatment continued or discontinued). He also highlighted case law that, where there is compelling evidence of a person’s wishes, treatment may be continued even if based on belief in miracles and even if clinicians view it as futile from a medical perspective. A key authority referred was the TG case (Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust v TG & Anor [2019] EWCOP 21’)

Based on the evidence presented to the court, he said, there was no doubt or dispute about what XY’s wishes would have been, and one certainly knew ‘on the balance of probabilities’ what she would have wanted in her current situation. It may not have changed the best interests decision by the court, but the failure to give sufficient weight to this evidence was a ‘fundamental flaw’ in the judge’s approach to the decision she made.

The Trust’s position

Mr Mylonas as Counsel for the Trust spoke next – and the judge invited him to focus on the two main points addressed by Counsel for the daughter (responsiveness and account taken of XY’s views).

The Trust took the position that there was no realistic prospect of the appeal succeeding and permission to appeal should not be granted.

On family evidence of responsiveness: Counsel for the Trust reiterated the strong medical evidence and drew attention to a statement by Dr Bell that XY is on the lowest point of the Prolonged Disorder of Consciousness spectrum (i.e. what would have historically been called a ‘Persistent Vegetative State’). He referred to the statement from Dr Bell that the suggestion that XY was responding would be outside all acceptable medical knowledge. The CoP judgment had drawn attention to these points and, Counsel for the Trust said, “It is a fundamental basis on which any assessment of Best Interests must unfortunately lie, notwithstanding the family’s sincere hopes and beliefs that there is some meaningful response…”. He informed the court that the nursing care in ICU was a ratio of 1:1 (information that had been sought by email during the hearing) and highlighted the fact that these were specialist nurses who would know how to distinguish a reflexive from a purposive response. Addressing a question the judge had raised about WHIM and SMART testing (two tools often used in assessing patients in Prolonged Disorders of Consciousness), Counsel for the Trust explained that such tests were not typically used in ICU but, “with XY, there was CRS, Coma Recovery Scale, testing carried out which was conducted daily….that has showed a deteriorating condition with no improvements” although “regrettably those documents were not in the documents that were before Her Ladyship”.

On what XY would have wanted: Counsel for the Trust submitted that there were some overstatements by Counsel for XY’s daughter of what could be derived from XY’s past conversation because, as the judge properly identified, the issue had never been discussed with XY. He contrasted this with the specific statements reportedly made in the TG case – albeit unfortunately not quoted in the TG judgment. He drew attention to statements from family about XY being a fighter and about her love of life – a life to which she could, in fact, never return according to all the medical evidence. In response to submissions on behalf of the daughter that she would have wanted life at any cost, Counsel for the Trust concluded:

“She would never have envisaged this cost…this level of intervention and invasiveness would not be in [her] consciousness or contemplation…she undoubtedly did say, and would have said, to her daughter and those around her that she valued life, because of what it gave her: the opportunity to play with her grandchildren, her children and engage with all those around her. She can never do that. And the cost of her subsistence now – because it’s not even an existence at the level it currently is – that is, we say, far too grave a weight for her to bear…” [2hrs 23mins into the recorded version of the hearing]

The Official Solicitor’s position

The Official Solicitor acting as XY’s litigation friend was the last barrister to address the court. Ms Roper KC argued, on behalf of XY herself, that permission to appeal should be refused.

On family evidence of responsiveness: She referenced the medical evidence about the condition of XY’s brain as already outlined by Counsel for the Trust and, like him, reiterated that what the family reported about responsiveness would be – as one of the medical experts had said – ‘outside all accepted medical knowledge’. Doctors, she said, were not challenging what the family say they saw: their point was that the movements they saw did not indicate awareness or responsiveness, as the family believed. She drew attention to an attendance note from an agent the OS instructed to visit XY: it confirmed that nursing staff caring for XY also (like the doctors) saw XY’s movements as reflexes not volitional responses. Nurses who witnessed XY’s movements during family visits said the same thing.

On what XY would have wanted: Ms Roper acknowledged the very clear evidence that XY was a deeply religious woman. The OS position was that Mrs Justice Arbuthnot had meticulously set out the family evidence but was not persuaded that this evidence allowed one to infer that XY would have wanted to remain on intensive care for the rest of her life. The family witnesses had not engaged with that outcome, she said, because they retained a belief that XY was responding to them and that there was potential for recovery.

Re the TG case (used as an authority by Counsel for XY’s daughter), the OS pointed out that TG had made very specific statements and that TG’s circumstances were different from XY’s circumstances in that the application was made very soon after injury (just two months compared with six months in this case) and also that it was possible for TG to leave intensive care and be transferred to a nursing home and a life not exposed to continuous invasive treatment (which was not medically achievable for XY).

Counsel submitted that the judge had considered the family evidence about responsiveness and about what XY would have wanted, ‘but ultimately did not agree’ with what the family thought on either matter. And the judge was entitled to be of this view on the evidence.

The hearing concluded with submissions about what would happen if the court refused the application to appeal – and there was a plan, were that to be the case, to give some time (5 days) for the family to engage in discussion of end-of-life care (as they had not yet felt able to do this) and for withdrawal to take place after that. (I worried about this being perilously close to Christmas.)

Finally, Mr Thomas reiterated XY’s strongly held religious views and that: “those views, I would submit, are far more likely to persist, and far less likely to change, based on the individual circumstances one finds oneself in”.

The judge ended the hearing by thanking the applicant (XY’s daughter) for her work in bringing the case to court – reflecting the whole framing of the ethos of the court as co-operative and respectful.

The Court of Appeal judgment

Permission to appeal was refused.

On the first main grounds of appeal (that the judge had not given sufficient weight to family evidence of responsiveness), Lord Justice Baker stated in the judgment that:

“It may be that [the daughter] was not cross-examined on her observations. But the challenge came from the unanimous evidence from the clinical and nursing staff that they had seen nothing to indicate any awareness in XY, and from the clinical and expert evidence that the evidence from CT scans and EEG recordings was indicative of a PDOC [Prolonged Disorder of Consciousness] at the lowest end of the spectrum.”

The judgment goes on to state:

47. … the judge was plainly fully aware of the extent of the evidence from family members about XY’s responsiveness. ….

48. The judge gave conspicuously careful attention to all of the evidence about this issue [of responsiveness]. Her decision to prefer the evidence of the clinical and nursing staff about the extent of XY’s responsiveness, and the interpretation of the evidence advanced by Dr Bell and Professor Wade, was plainly open to her on the evidence. There is no real prospect of the Court of Appeal finding that she was wrong to reach that conclusion.

On the second main ground of appeal (that the judge had not given sufficient weight to family evidence as to what XY would have wanted), the judgment does not address the issue of whether family/friends were cross-examined and had relevant questions put to them, but says:

52: … [Mrs Justice Arbuthnot’s] evaluation of the evidence of XY’s wishes and feelings, beliefs and values, was conducted in accordance with s.4(6) and (7) of the [Mental Capacity] Act. But important though her beliefs and values undoubtedly were, they were one factor in the overall evaluation of best interests. They had to be considered in the context of the totality of the evidence.

53. In this case, the magnetic factor in the judge’s evaluation was the evidence about XY’s medical condition…

54. The judge was obliged to consider the family’s clear evidence about XY’s faith in the context of her present circumstances which, as Mr Mylonas submitted on behalf of the Trust, she could never have envisaged. As Ms Roper submitted for the Official Solicitor, the fact that she had a religious faith, and believed that it is God’s choice when someone lives and when someone dies, does not lead to an inference that she would have wanted to continue treatment in these circumstances. There is also force in Ms Roper’s further submission that the family’s views about what XY would have wanted are situated in their belief, contrary to all the medical evidence accepted by the judge, that there is a prospect of recovery.

55. In those circumstances, there is no real prospect of the Court of Appeal concluding that the judge erred in her approach to XY’s beliefs and values and wishes and feelings.

The CoA judgment goes on to state:

…I have no doubt that the judge took their strong views about XY’s wishes and feelings into account, as she was required to do under s.4(7). But she was entitled to entertain doubts about what XY would have really wanted in these terrible circumstances, and equally entitled to conclude that the family’s evidence about her wishes and feelings was outweighed in the best interests analysis by other factors, in particular her very serious and deteriorating medical condition. As she said in her conclusion, “the futility of continuing further treatment and the increasing deterioration of XY’s brain outweigh the family’s views and what they consider might have been XY’s views in the circumstances.”

The full judgment can be read here: Re XY (withdrawal of treatment) [2024] EWCA Civ 1466

Reflections: what would P want? And who knows?

The place of a person’s own wishes in relation to medical treatment was central to this case.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 is the key statute here. A person with capacity has the right to refuse or consent to any treatment on offer (they cannot demand treatments). They can also document refusals in advance in a legally binding ‘Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment [ADRT] (although very few people do this – for how to do so, see the ‘Compassion in Dying’ website).

Once someone has lost capacity to refuse or consent to a treatment then (if there is no ADRT) the choice between available treatments becomes a best interests decision. What someone would have wanted then becomes only one component in that decision – and, of course, what they would have wanted may itself be subject to challenge, as demonstrated in this case.

Issues that played out in this Court of Appeal hearing in a variety of intersecting ways revolved around questions such as:

- What can one infer from what one understands of someone’s values and who can do so most accurately?

- How might someone’s values or wishes change in specific circumstances, and how does that relate to the nature of those circumstances and the nature of their values (or beliefs, wishes, feelings)?

- Who is the ‘someone’ whose wishes are considered (the ‘person before’ or ‘person after’ injury?)

- How much weight should a person’s prior wishes be given in a best interests decision in relation to other factors?

- and anyway – in the case of wanting (as opposed to not wanting) treatment “we cannot always have what we want” (Lady Hale in Aintree) – even if one has capacity to make the decision.

There is a large academic literature that explores some of these issues – ranging from surveys of doctors’ or families’ accuracy in predicting a person’s treatment preferences, or how people’s views shift when faced with severe disability, right the way through to philosophical debates about personhood and autonomy. Readers of this blog will no doubt have their own personal views about the proper answers to these questions as they reflect on their own values and wishes, and those of people close to them.

I’ve written about some of these debates previously e.g. in relation to the Paul Briggs’ case (‘When ‘Sanctity of Life’ and ‘Self-Determination’ clash”). My aim in the final paragraphs of this blog post is different. I want to explore the implications for family and friends involved in best interests decision-making about serious medical treatment.

What do families experience when they have sought to promote what they believe their family member would want – and when that is reinterpreted through the lens of a formal best interests process and/or over-ruled?

Of course, families are not inevitably the best people to advocate for a patient – they may not know what the person would want, or (if they do) they may not wish to advocate for it; they may be distracted by family conflict or trauma or simply overwhelmed by their own needs. But sometimes families are exactly the right people to promote ‘P’s voice’ – and that is the strong sense I got with this family.

The idea of what their mother, niece or sister would have wanted (in line with her, and their own, religious faith) was clearly a central guiding light – and, for them, a key determinate of the right way forward. They had conveyed a very strong sense of what those wishes would have been during the Court of Protection hearing, and demonstrated a remarkable resilience in the face of any challenge from expert evidence about XY’s condition and prognosis (which I suspect, XY would have demonstrated too).

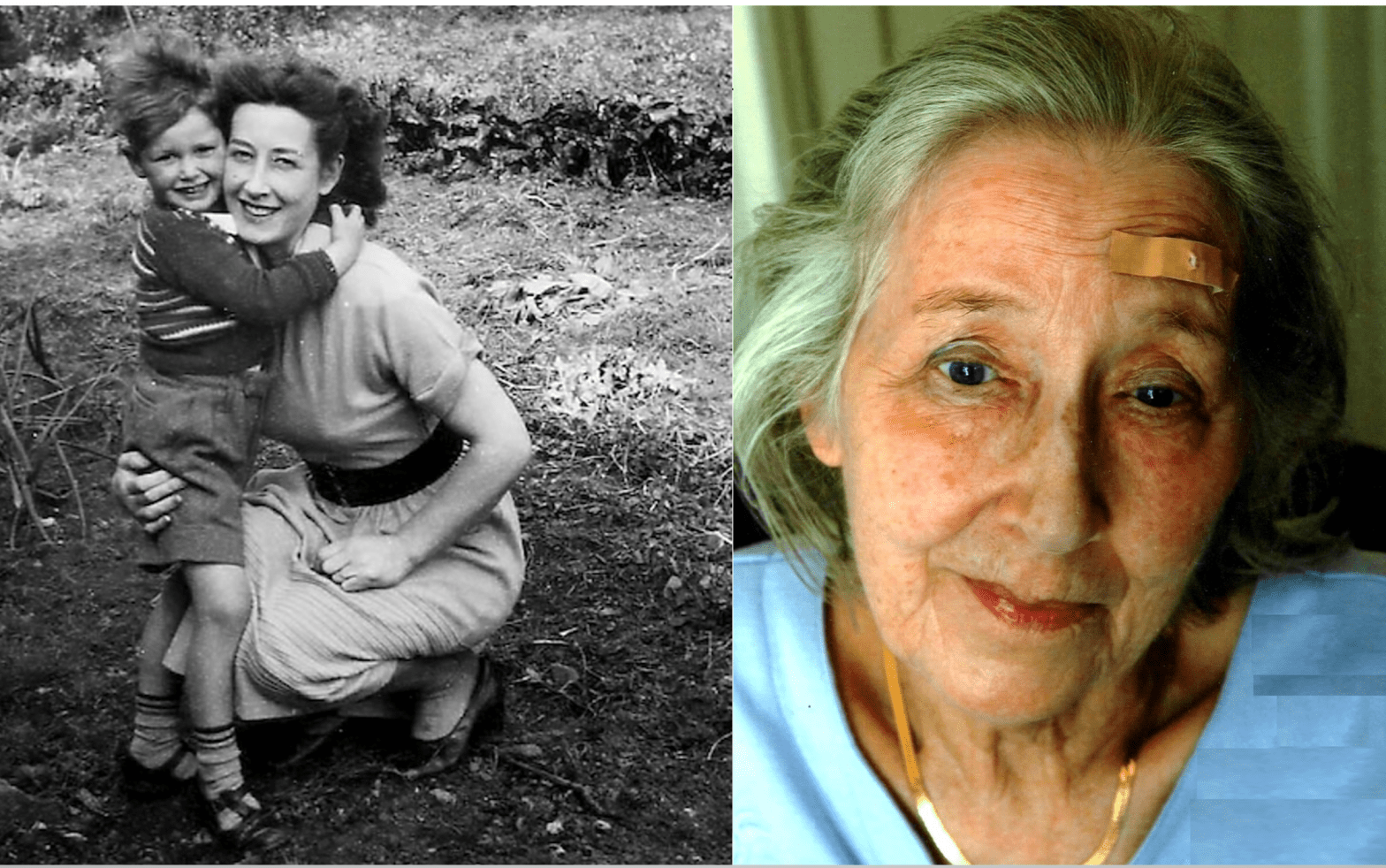

I felt huge empathy for this family, and it resonated with my own experience after my sister, Polly Kitzinger, suffered catastrophic brain injuries back in 2009. It resonated even though, on the face of it, the experience of this family and mine might be thought to be diametrically opposed.

For a start, XY and Polly were very different people: XY was a woman of faith, Polly was an atheist; XY believed in the sanctity of life, Polly did not; XY believed in miracles, Polly did not; XY believed in submitting to the will of God whereas Polly insisted on her own will determining all her choices and what happened to her body, her life, her death.

And as families, XY’s family and mine argued for different outcomes: XY’s family fought to have XY’s life-sustaining treatment continued, whereas we fought to try to have treatment discontinued. I wrote about this a couple of years after Polly’s injury (https://www.thehastingscenter.org/m-polly-and-the-right-to-die/) and gave an interview to the BBC in 2018 about the ongoing aftermath. (I know lawyers and judges will dislike the word “fought” in this paragraph – but that is how it often feels to families, despite the purportedly ‘non-adversarial’ approach of the Court of Protection.)

What XY’s family and my own family share is that both were committed to trying to represent ‘what the patient would have wanted’. Both they and we had a strong sense we knew what that was. Both XY’s family and mine, to a greater or lesser extent, shared some of the patient’s core values – though, personally, I found Polly’s emphasis on autonomy, choice and control a little extreme!

Relating then to my own experience, I wondered how this family, and the community of friends around XY, experienced the formal best interests processes in the hospital and in the Court of Protection; how they felt about the arguments in the CoP judgment, and how they experienced their encounter with the Court of Appeal.

In my original blog about the CoP hearing in early November I wrote that: “everyone in court was careful first to acknowledge XY as the individual at the centre of the case and make it clear that her family and friends had been, and would be, heard”.

In rounding off my summary of what family and friends had said I wrote: “The clinicians listening in court, and the judge, could have been left in little doubt about the values and beliefs that informed XY’s approach to life – and what those who knew and loved her believed to be the right way forward.”

The family were treated respectfully and sensitively in the Court of Protection. I suspect they did leave court feeling ‘heard’. There may have been an element of ‘therapeutic jurisprudence’ in the experience.

But I wonder how it felt to family and friends when the Official Solicitor, who is charged with responsibility for representing XY, took a position that (the family believe) is diametrically opposed to what XY would want. I wonder too whether the judgment came as a shock – not just the outcome, but whether parts of the framing of the judgment felt particularly egregious.

Suggestions in the judgment that their discussions with XY had not been specific enough, or that she might (had she been able to) change her mind when faced with the realities of her medical situation (as defined by the medical experts) might well feel very disrespectful now – both to their evidence and to the strength of XY’s own faith.

They may have been distressed by the fact that the judge extrapolated from what they said to come to a different conclusion: for example, rather than valuing being a ‘comfort’ to her family (as testified to the court by XY’s close friend) the judge speculated that XY might want to be allowed to die so that her family would be ‘relieved of the long drawn out pressure they are under’. This might seem like twisting their own words against them or speculation on matters which they had not been invited to engage with in the hearing. There was also very little challenge or cross-questioning of the family – which, at the time, seemed a kindness, but in retrospect was maybe a problem, as they may have felt they had no opportunity to rebut challenges to their evidence.

Knowing my own sister’s values and beliefs (although these were not religious), I felt fully able to infer what Polly would have wanted, despite never having discussed her precise medical wishes if she were to experience severe brain injury. I would have welcomed the opportunity to specify what I knew, and how I knew (under cross-questioning if necessary). I also agree with the submissions on behalf of XY’s daughter that someone’s core values, embedded not just in what they say but in the way they live their life, “are far more likely to persist and far less likely to change, based on the individual circumstances one finds oneself in”.

Family and friends may, of course, be wrong in what they infer, but at least they have years of context for their inferences. It may be hard to believe that the proposed alternative inferences made by judges are likely to be more accurate (even if those take into account a medical ‘reality’ that the family themselves refuse to accept).

A person’s wishes, what they want to happen, are not determinative in best interests decision-making. There are many COP judgments in which it is accepted that the protected party wants one thing (to go home, to have sex with someone, to have contact with family, to use the internet) that it is not in their “best interests” to do. And so, the judge makes a decision contrary to what that person wants.

I wonder whether judgments which go against what a family believe to be what someone would have wanted are more painful to hear when it seems that the judge has not fully believed a family’s account of that person’s wishes and what that means for the present circumstances. Could this leave family members feeling they could – should – have done more to explain and persuade and provide evidence, so that the judge could really understand the person?

An alternative judicial strategy would be simply to make a best interests decision to over-ride what the judge accepts the person would have wanted (in circumstances of course, where they do accept it!). That might look like a naked exercise of judicial power (and responsibility) – and it is. But, given the ‘magnetic factor’ in the judge’s best interests evaluation in this case was XY’s medical condition and the futility of intervention –perhaps this would feel less undermining, than (in effect) refusing a family’s lifetime’s knowledge and experience of P’s fundament values and beliefs.

That brings me full circle to the point I made in my blog about the original Court of Protection hearing: perhaps, given the clinical realities, doctors should simply have said that life-sustaining treatment was no longer an available option.

Jenny Kitzinger is co-director of the Coma & Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre, and Emeritus Professor at Cardiff University. She has developed an online training course on law and ethics around PDoC and is on X and BlueSky as @JennyKitzinger