By Celia Kitzinger, 9th March 2024

Readers of The Times probably imagine theirs is a superior sort of newspaper.

It’s the oldest national daily newspaper in the UK (founded in 1785) and has been widely seen as the “paper of record” on public life. It proclaims itself to be a source of news that readers “can trust for honest journalism that informs, entertains and analyses without bias”. In 2018 The Times was named Britain’s most trusted national newspaper by the Reuters Institute for Journalism at the University of Oxford.

So, I was surprised to discover that last month The Times took paragraphs from a press release sent out by the campaign group Christian Concern, lightly edited, reordered and paraphrased them, and passed this off as original journalism by their Legal Editor, Jonathan Ames.

The 676-word article in The Times, published on 8th February 2024, is reproduced in its entirety in Appendix A. Take a look.

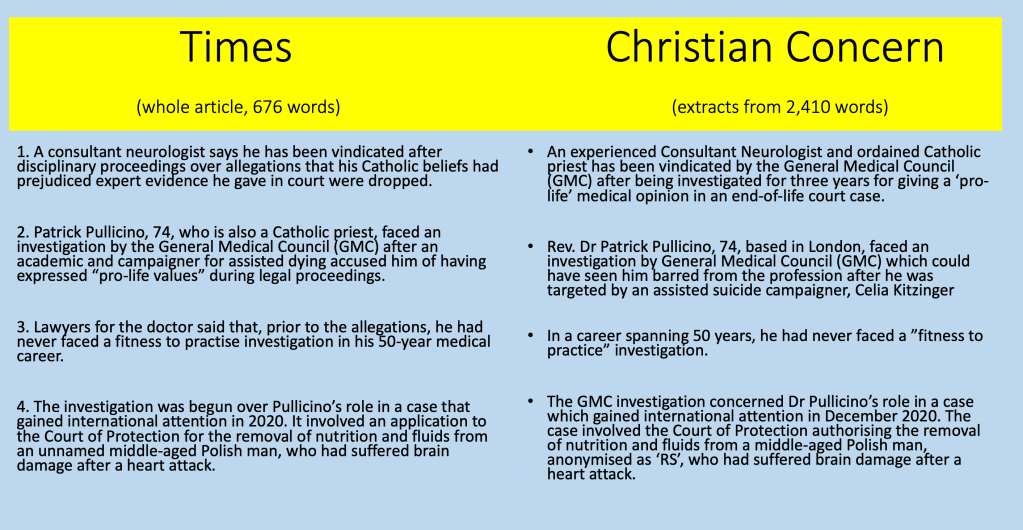

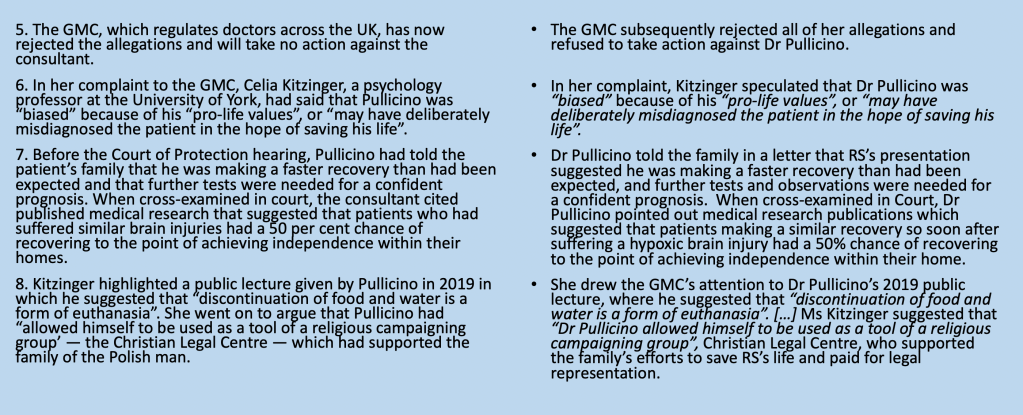

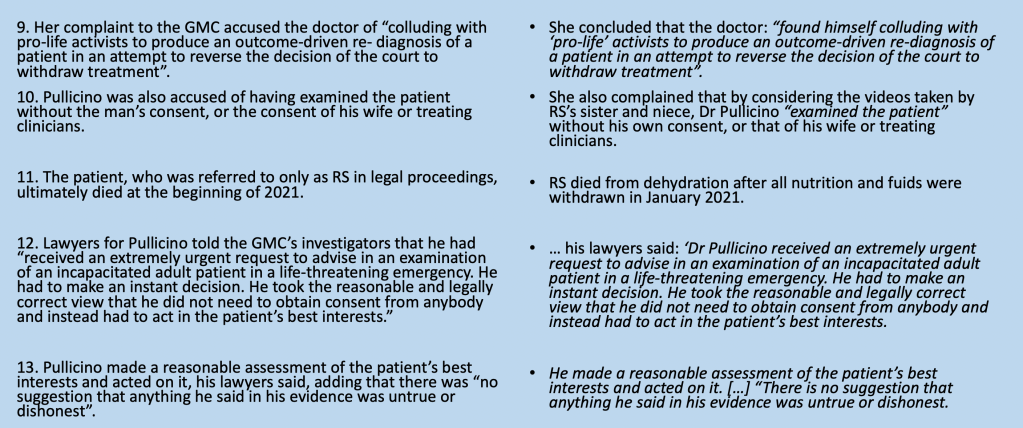

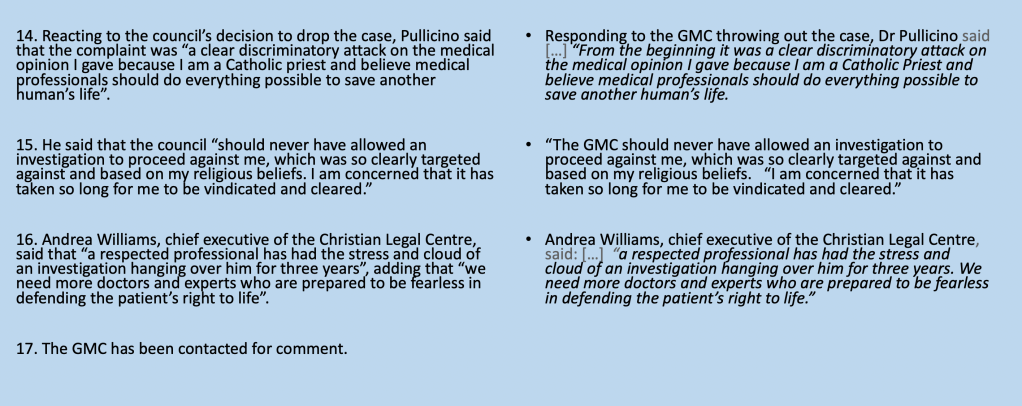

There are 17 paragraphs to the article. I’ve reproduced them in the left-hand column. Now look at the right-hand column and you can see that everything except the last sentence is taken either verbatim (for quotes attributed to other people) or paraphrased from the much longer Christian Concern press release. There’s no information in Mr Ames’ article that isn’t also in the press release.

Jonathan Ames is described by The Times as “one of the leading law journalists in the UK… with extensive knowledge and experience in the field… an invaluable resource for those seeking reliable and comprehensive information on legal matters”. None of that knowledge or experience is on display in this article. It relies solely on the press release for “information on legal matters”. That’s means it’s neither “reliable” nor “comprehensive”, and it can’t be trusted.

This looks horribly like a paradigm case of what Nick Davies, award-winning journalist and author of Flat Earth News, calls “churnalism” – the recycling of unchecked second-hand material, with a misleading byline making it look as though a respectable journalist has authored the piece. Churnalism, says Nick Davies, leads to falsehood, distortion and propaganda in the global media.

Many journalists I’ve discussed this with find the fact that a story in The Times was substantially drawn solely from a press release entirely unsurprising. Rewriting from press releases goes on all the time, I’m told – that’s how most journalism is done these days.

The “exposé” by Nick Davies and the Cardiff University researchers whose research underpins his book was published in 2008. It shows a “tide of churnalism” across “all local and regional media outlets in Britain” produced by “journalists who are no longer out gathering news but who are reduced instead to passive processors of whatever material comes their way, churning out stories, whether real or PR artifice, important or trivial, true or false” (p.59). This revelation may have shocked readers when it was first published, but sixteen years later, well, it’s just how journalism is.

I’m even told by some journalists that Jonathan Ames may not have “filed the copy” – meaning that it may not actually have been him who rewrote the press release that appears under his name: it might have been another staff journalist and Mr Ames might not even have known that authorship had been attributed to him until after it appeared in print.

Although it’s common to hear sweeping claims from world-weary cynics to the effect that you can’t trust anything in the news these day (I may even have said this myself on occasion), that doesn’t translate into an understanding of the way the system works to manufacture “news” or how it influences what we think we know about the world – or that “Britain’s most trusted national newspaper” is implicated in exactly the same practices as the “inferior” newspapers its readers tend to disparage.

So, what I’ve tried to do here is offer a concrete, specific, forensic analysis of how one piece of “news” was created – from its origins in a case about life-sustaining treatment in the Court of Protection, through its subsequent life as a complaint to the General Medical Council (GMC), then as a press release from Christian Concern, and eventually as a story in The Times.

I can do this because I am part of the story and have masses of documentary evidence about what happened. I was present as an observer in the court case. It was me who made the complaint to the GMC. And I feature in the press release and in The Times story. I have a personal stake in finding out what went on, and how this kind of “news” is manufactured.

Unchecked ‘spin’

Christian Concern is a pressure group whose mission is to equip people “to be an effective ambassador for Jesus Christ in today’s culture”. That mission obviously represents a particular perspective not shared by many people who are adherents of other religious faiths, or none. Nobody expects Christian Concern to be impartial. Their faith-based perspective naturally affects the way they see and report on the world, and the angle they take on stories. Whether or not the information they put out is truthful and accurate, it is always selected and designed specifically to promote their own campaigning goals. Even other Christian publications recognise that Christian Concern is a “self-publicising outfit” engaged in “assiduous publicising of their own lawsuits” (Church Times, 4 March 2024).

It should go without saying that serious mainstream journalists should not simply reproduce information from Christian Concern (or any other pressure group) under their own byline, because that risks the uncritical reproduction of one particular spin on current affairs. They need at the very least to fact-check and to seek out comments from other points of view. “Journalism without checking is like a human body without an immune system”, says Nick Davies.

But there’s no evidence of any fact-checking in The Times article – nor any attempt to access other perspectives.

I feel strongly about this because the article names me, gives false information about me, and uncritically reproduces an accusation from a Catholic priest, Dr Patrick Pullicino, that I “targeted” him in a “discriminatory attack … based on [his] religious beliefs”.

Nobody from The Times contacted me to check the story before publication, or asked my opinion about the events reported in the article.

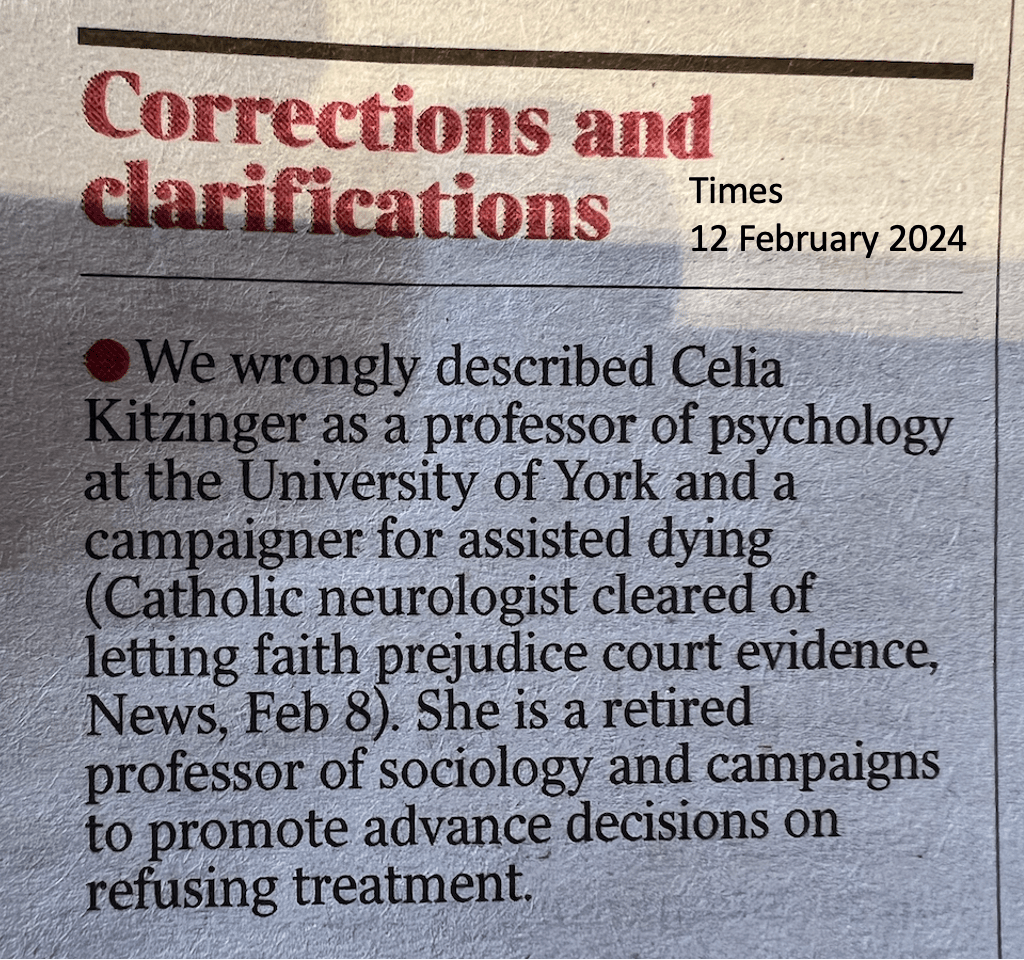

Consequently, the article as originally published had obvious factual errors, which could have been easily discovered with a simple google search. I am neither a professor of psychology at York, nor a campaigner for assisted dying, as The Times originally claimed. A “correction” was published in the print version (The Times, 12 February 2024, see Appendix B) and the online version has now been edited to correct this misinformation.

Nor have I ever attacked Dr Pullicino for his religious beliefs. I disagree with many things that Dr Pullicino has said and written, but I defend his right to hold the views he does, to express them publicly within the constraints of the law, and to live in accordance with his faith. A journalist for LifeSiteNews asked whether I believe that health care professionals with “pro-life” views should leave the profession. Of course not: “That would be to deprive the medical profession of many fine doctors and other health professionals, and it would be an unconscionable threat to their freedom of belief“.

Other media outlets – unlike The Times – did seek out my views in advance of publication and published my rebuttal of Dr Pullicino’s claims as part of their reports. The ‘far right’ Epoch Times published a piece (here – requires registration to view) based on the Christian Concern press release, but accurately incorporating my perspective. There’s a fair and accurate report on the Catholic conservative advocacy website LifeSiteNews: it’s clearly oriented for a Catholic readership whose sympathies will naturally be with Dr Pullicino rather than with me, but it’s well-written, acknowledges – as The Times does not – my academic expertise in the medical condition Dr Pullicino was giving evidence about, and gives adequate space to representing my views. It’s based on original journalism and independent research.

Shamefully, The Times simply relied solely on the partisan, unchecked, press release – and when I asked for a ‘right of reply’ I was told only that I could submit a letter about end-of-life decision-making to the Editor for consideration. I was not tempted by this offer. An invitation to (possibly) publish a letter does not constitute a “right of reply” – nor does the suggested subject matter engage with my concern about having been accused of a religiously-motivated targeted attack on a Catholic priest.

What The Times needs (in my view) is proper legal analyses of cases like this one – involving doctors with disputed expertise and wider issues relating to end-of-life decision-making in the courts. Legal analysis should not be relegated to the “Letters” page and written by members of the public. It should appear on the law pages of The Times. That’s what a Legal Editor is for.

So, this blog post is, in effect, my “reply” to the misleading version of the story published in The Times, and it offers an alternative legal analysis of the story.

What was the story about?

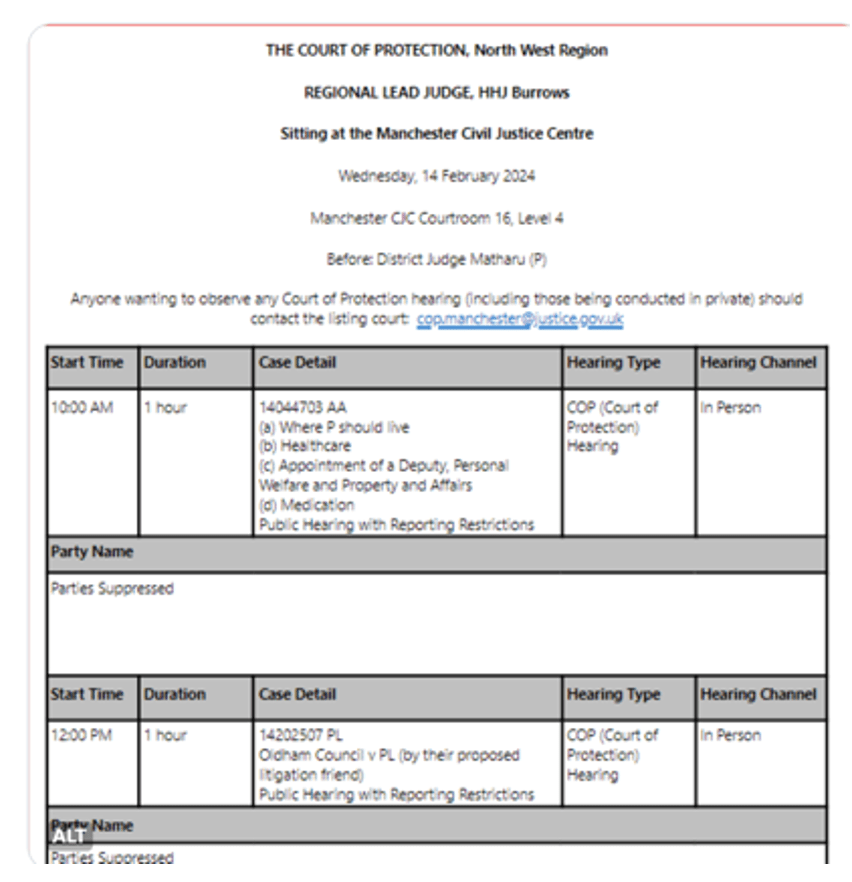

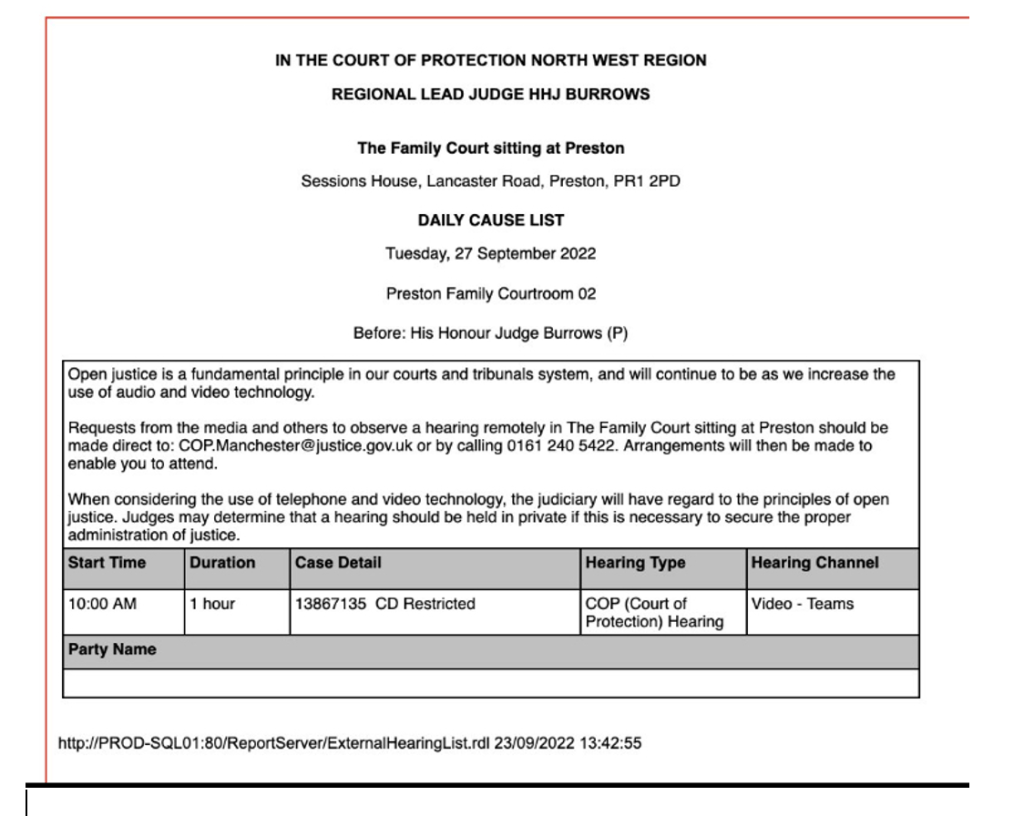

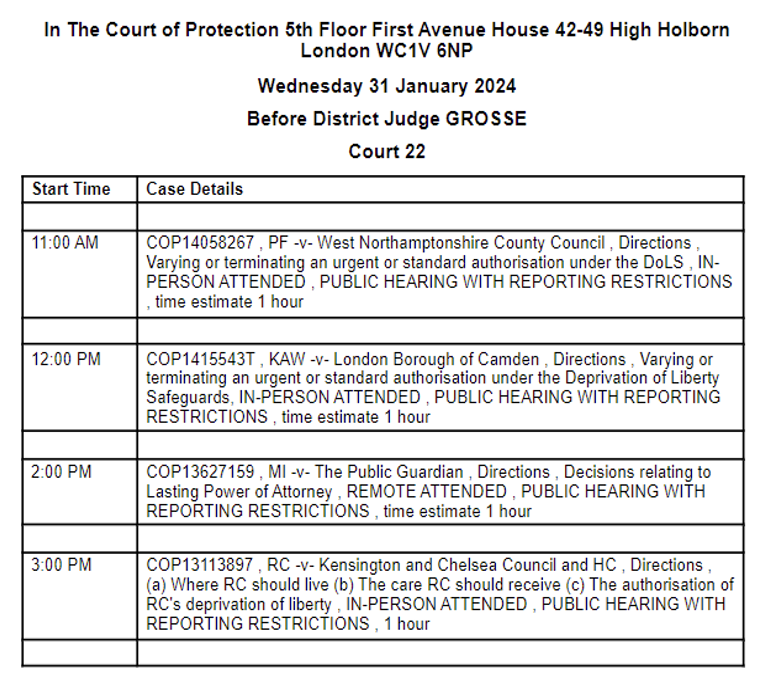

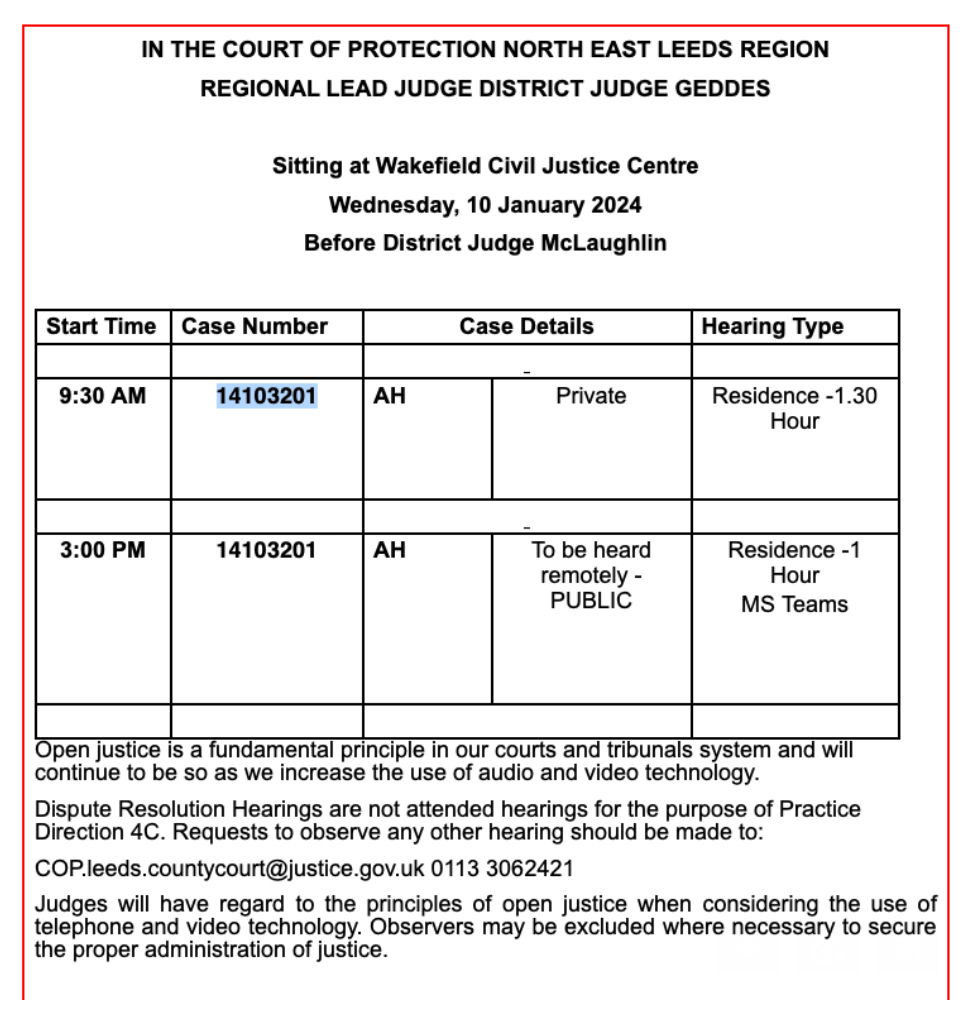

It all started with a case in the Court of Protection back in 2020. I attended four successive hearings in this case (held remotely via video-link) and wrote a blog post for the Open Justice Court of Protection Project (see Faith, Science and the objectivity of expert evidence).

The case was about whether or not to continue life-sustaining treatment for a man in a “prolonged disorder of consciousness” (ie. a vegetative or minimally conscious state). The court-appointed expert had diagnosed him as “vegetative”.

I was interested in this case because I co-direct “Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre” at Cardiff University and co-authored the Royal College of Physicians Guidance on “Prolonged Disorders of Consciousness following Sudden Onset Brain Injury”. The subject matter of this case is firmly at the centre of my academic expertise.

The hospital Trust took the view that continuing treatment was not in the man’s best interests. His wife agreed. She believed he would want to refuse the treatments that were keeping him alive (notably, clinically assisted nutrition and hydration). His Polish “birth family” (mother sisters, and niece) disagreed. They believed that, as a Catholic, he would want to continue to receive treatment.

The case was heard by Sir Jonathan Cohen, who found that continuing treatment was not in the patient’s best interests, and authorised withdrawal. The judgment is publicly available here: University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust v RS & Z [2020] EWCOP 70.

A couple of weeks or so after this judgment was handed down, Dr Patrick Pullicino, who is an experienced neurologist as well as a priest, became involved. It appears from what he said in court that he learnt about the case in part from Pavel Stroilov, who works with or for the Christian Legal Centre, a “sister organisation” to Christian Concern.

Under circumstances that were strongly criticised by the judge as a “deplorable ruse”, he examined the patient via video-link and then gave evidence in court that the patient was doing better than expected, was likely to be in a “minimally conscious state” – or on the way to becoming so – and could make a reasonable recovery.

The judge rejected that evidence, and declined to appoint Dr Pullicino to produce a further (full) report. He found Dr Pullicino’s evidence “unaccountably vague”, had “severe misgivings” about its quality, and was “concerned about the level of [Dr Pullicino’s] objectivity“. Ultimately the judge was of the view that “I do not think I can place any weight on the evidence of Dr Pullicino” (all quoted from Z v University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust & Ors (Rev 1) [2020] EWCOP 69).

Supported by Christian Concern and/or the Christian Legal Centre, the ‘birth family’ then made an application to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

The judges in the Court of Appeal dismissed their application. They said Dr Pullicino’s evidence “lacked every characteristic of credible expert evidence and it is not surprising that the Judge rejected it as effectively worthless” Lord Justice Peter Jackson). It was based on “partially informed or ill-informed opinion” (Lady Justice King) (in §21 and §31 Z v University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust (NO 2)). Both judges were determined “to ensure that [the patient’s] best interests are not prejudiced by continued unfounded challenges to lawful decisions” (§28 & §32) – and both expressed concern about the effect of Dr Pullicino’s evidence and the consequent continuing legal challenges for “[the patients’s] wife and children, who are having to endure proceedings that, coming on top of his loss from their daily lives, must be deeply distressing to them” (§28 & §29).

All these criticisms of Dr Pullicino’s evidence are in the public domain, in published judgments on public websites The judicial comments were also picked up, reported, and commented on across a range of law-related internet sites (e.g.“Judicial Criticism of an Expert Witness – Lessons Learnt”).

I contacted the General Medical Council (GMC) because it is concerned with, and offers to investigate, behaviour that might damage “the public’s confidence in doctors”. On the basis of what I’d seen in the Court of Protection hearing and read in the published judgments and in the subsequent legal uptake of it, I believed that Dr Pullicino’s behaviour was indeed such as to damage the public’s confidence in doctors. So, I wrote a “Letter of Concern” to the General Medical Council (sent 12th April 2021).

Three long years passed. I received occasional updates from the GMC on the basis of which it’s clear that this period of time was mostly accounted for not by active investigation but delays caused by correspondence being sent to the wrong address, waiting for transcription of court proceedings, and relevant experts being unavailable over the summer breaks.

Eventually, the GMC decided there was no need to take any action against Dr Pullicino and sent me a (redacted) “final outcome letter” dated 2nd January 2024.

In early February 2024, Christian Concern distributed their press release announcing the news of Dr Pullicino’s “vindication” – and their version of events was uncritically reproduced in The Times.

What’s wrong with The Times?

One serious problem with effectively reproducing a campaigning group’s press release in a “paper of record” without acknowledging it as such is that it disguises the source of the story. People are likely to understand that a press release from an organisation called “Christian Concern” will take a particular angle. By contrast, when the same information appears under the name of Jonathan Ames, Legal Editor of The Times, it acquires the spurious and unjustified aura of objective journalism.

By obscuring the source of the (mis)information, and by publishing it in a “trusted” national newspaper under the name of their legal editor, The Times amplifies the voice of the Christian Concern campaign, and credentials it as ‘legal news’ for the ‘mainstream’ (centre-right) readership of “one of Britain’s oldest and most influential newspapers”.

It’s often said, these days, that journalists simply don’t have time to do original journalism. Journalists are working against the clock, targeted by campaign groups, and under pressure to get the stories out. They’re encouraged to focus on the accuracy of quotes they are running, but not their truth, or even their context.

“Flat Earth news has gone global” says Nick Davies because of “takeover by new corporate owners, cuts in staff coupled with increases in output, less time to find stories and less time to check them, the collapse of old supply lines, the rise of PR and wire agencies as an inherently inadequate substitute, less and less input being repackaged for more and more outlets, truth-telling collapsing into high-speed processing” (p.97)

There are very few journalists in court these days. I’ve only ever seen a handful of journalists in attendance (and only at the Royal Courts of Justice, never in the regional courts).

Although Jonathan Ames has published several pieces for The Times about Court of Protection cases, I’ve never seen him in court.

Mr Ames wasn’t in court for the hearing at which Dr Patrick Pullicino gave evidence – or for any of the other hearings about the patient upon whose diagnosis and prognosis Dr Pullicino gave his opinion. I watched all of them as they happened, and I read the judgments.

I’ve observed more than 500 Court of Protection hearings since Spring 2020, when the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic led to hearings being conducted remotely – starting with the first ever all-remote hearing on 17 March 2020. Other journalists were there – but not Jonathan Ames. In his subsequent article reporting (in passing) on that first all-remote hearing as an instance of the “courts’ tech solution to coronavirus crisis” (9 April 2020, The Times – paywall), Jonathan Ames quotes from something I wrote – but without giving the source of his information. The daughter of the man at the centre of that first all-remote case said it was “a second-rate hearing”: she felt deprived of her “day in court and the ability to look the judge in the eye”. The original source for those quotations is my blog post, published on the Transparency Project website: “Remote justice: A family perspective”. Not only was I in court for the whole three-day hearing, I also interviewed the daughter – and so it was my report on which Jonathan Ames relied.

Looking back at the “legal” articles in The Times over the last few years, I’ve found many other pieces under Jonathan Ames’ byline that depend heavily on Christian Concern press releases.

Here are two examples – both of which follow the same formula as is used in the story about the “vindication” of Dr Pullicino. Each article contains only information from the Christian Concern press release and nothing more. Each reorders and paraphrases that press release and adds a closing sentence which gestures towards an unarticulated ‘alternative’ perspective which never materialises.

- “Nurse sues hospital over ban on wearing a cross” (5 October 2021, The Times – paywall) This is a part-verbatim, part-paraphrased and reordered version of the Christian Concern press release of 5 October 2021 with the headline, “Christian nurse takes legal action after being ‘treated like a criminal’ for wearing cross necklace”. The only information in The Times that is not also in the press release is the last sentence: “A spokeswoman for the trust said it would not comment on active legal proceedings”.

- “Lecturer ‘threatened him with terrorism referral over views on homosexuality’” (24 November 2023, The Times – paywall) This is a part-verbatim, part-paraphrased and reordered version of the Christian Concern press release of 24 November 2023 with the headline, “Christian theologian sacked for tweet on human sexuality and threatened with Counter-Terrorism referral takes legal action”. Again, the only information in The Times that is not also in the press release is the last sentence: “The college declined to comment on the legal action”.

On receipt of a Christian Concern press release, journalists have choices. At one end of the scale, they can dismiss it as biased campaign material and ignore it. At the other end, they can edit it straight into a story, as The Times has done. And in between those extremes, there are legitimate journalistic options like: contacting and quoting from other groups or individuals with opposing agendas to flesh out the story, or using the press release as a hook for telling a related story, e.g., about the conduct of the GMC or the problems faced by expert witnesses in the courts, or the challenges of end-of-life decision-making.

Spin by omission

The term ‘spin’ is often used (without any necessary implication of dishonesty or manipulation) to recognise that there are different perspectives on the same story, and that a story can read very differently depending on how it is told, what information is selected for inclusion and what is left out, and how it is framed up to promote a particular interpretation for its readers.

The ‘spin’ put on these events by Christian Concern is that a blameless Catholic doctor, seeking to save the life of another human being, was targeted – first by the judiciary and then by a “campaigner for assisted suicide” (that’s me, mischaracterised!) who launched a discriminatory attack on his religious beliefs and reported him to General Medical Council. That regulatory body then conducted an inappropriate, unnecessary and prolonged investigation into his fitness to practice before deciding there was no evidential case to answer. From this perspective, the story underscores Christian Concern’s repeated message over the last few years that Christianity is facing marginalization and exclusion from the public sphere by an intolerant form of secularism. This is a claim identified by political scientist Steven Kettle as commonly deployed by conservative Christian groups in their attempts to influence national level policies and debates.

The Times’ reliance on the Christian Concern press release for the Pullicino story means that it too tells a narrative of Christian persecution – with the same strategic omissions as the press release. Because the version of the press release in The Times is pared down to a quarter of its original length, some information is omitted. These additional omissions all work to my detriment.

Like Christian Concern, The Times reports that Dr Pullicino and the Christian Legal Centre “supported the family of the Polish man” (see Appendix A §8). The piece omits to mention (presumably because the Christian Concern press release doesn’t either, so The Times didn’t know this) that there was a division within the family, who disagreed as to what the patient would want. Although the ‘birth family’ wanted treatment to continue, the man’s wife did not. So Dr Pullicino and the Christian Legal Centre were most certainly not supporting her.

Where Christian Concern (correctly) used the word “speculated” to refer to a comment made in my complaint to the GMC, The Times transforms what I labelled in that complaint as “speculation” in to something I simply “said” as if it were my settled position. And The Times omits (as does the press release) the very next sentence in which I dismiss as “unlikely” the notion that Dr Pullicino “may have deliberately misdiagnosed the patient in the hope of saving his life (see Appendix A §6). My own stated view was that “It is hard to believe that this would be the case, since this would be a gross violation of medical ethics – and it would surely be obvious that other medical experts could easily prove him wrong” (from letter of concern to the GMC). Omitting the context of a quotation is a familiar part of ‘spin’.

Finally, The Times (again, unlike the press release) omits any mention of the fact that a High Court judge and two Court of Appeal judges vigorously criticised Dr Pullicino’s evidence – leaving me as an apparent solo voice criticising Dr Pullicino in a legal void. This omission renders entirely invisible the fact that it was judicial criticism, above all, that was the source of my concern and motivated me to contact the GMC.

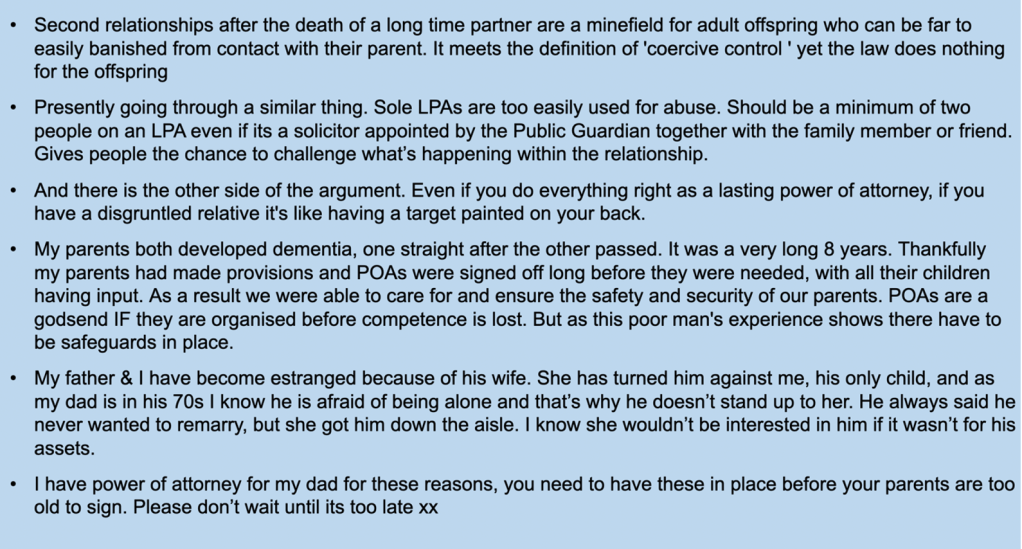

It’s hardly surprising, then, that the story came across primarily as a narrative about my allegedly discriminatory anti-Catholic behaviour – and resulted in unpleasant “below the line” comments from people accusing me of being a “bigot”, making a “hostile” and “ideological attack” on the hapless doctor and “wasting everyone’s time”. These people’s opinions have been manufactured by the slanted perspective of The Times article.

A plea for legal journalism

There are other ways of spinning this story which strike me as better fitted to the lofty aims of The Times as a paper of record, and to Jonathan Ames as Legal Editor.

In a democratic society, we badly need high-quality legal journalism to act as the ‘eyes and ears of the public’ in court, to ensure that justice is not only done but seen to be done, and to support the development of legal literacy.

One narrative The Times could have used is to highlight the failure of the General Medical Council to address what the judiciary has seen as serious problems with the way this doctor presented medical evidence in court – while continuing over the same period (much to the fury of many in the medical profession) to suspend doctors for fare-dodging or for falsely stating they’d been ‘promised” a computer.

Dr Pullicino admitted in court that he had not read the GMC guidance on “Providing witness statements or expert evidence as part of legal proceedings” – and he self-evidently did not act in accordance with those guidelines. Yet save for a minor matter of record-keeping, the GMC did not find him have done anything wrong.

Doctors and other medical and mental health professionals are widely used by the courts. Judges carefully consider their evidence in making their decisions. Justice depends on a respectful professional relationship between the judiciary and the medical profession.

Conversely, judges have recently been accused of accepting biased and controversial evidence from unregulated experts e.g. concerning parental alienation in the family courts – as in this report in the Guardian.

The Open Justice Court of Protection Project has also published concerns about expert evidence (e.g. When Expert Evidence Fails; When P objects to an expert; Standoff about the appropriate expert: A pragmatic judicial solution).

Judges do not have to accept the opinions of court experts, but they weigh heavily in their determination of cases. The Court of Protection uses a very small pool of experts and I’ve observed the same names coming up over and over again. Although the qualifications of these experts are impeccable and they almost always have extensive and up-to-date experience in the areas on which they are giving evidence, it can still be the case that another equally well-qualified expert might arrive at a different opinion. Very occasionally there are two or more experts in court with differing opinions (for example, Cancer treatment in the face of unknowns and expert disagreement).

The use of a small pool of experts obviously limits the court’s exposure to alternative equally expert views. This criticism is currently being voiced in relation to:

- protected parties with anorexia refusing feeding tubes (is the single expert most frequently employed by the court ‘giving up’ on anorexics too easily when he recommends no compulsory treatment?)

- women who may lack capacity in childbirth (do the experts advising the court have a ‘pro-life’ perspective with regard to the unborn child, since they seem invariably to recommend hospital birth, caesareans, and physical and chemical restraint to achieve this if necessary)

- people diagnosed with ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder’ (since this is a diagnosis that is not accepted as a genuine diagnosis by some psychologists and psychiatrists).

A substantial proportion of the cost of these experts, and the costs of the judges and legal professionals involved in commissioning and cross-examining the experts in these cases, comes out of the public purse. We have a public interest in ensuring that money is well-spent.

Any of us could find ourselves in court with a family dispute, an incapacitated loved one, or a relative at the end of life. We depend on judges to choose appropriate experts and we depend on those experts to do their job objectively. It’s in the public interest that any concerns about experts in court should be properly investigated by the appropriate bodies.

The GMC decision not to take any action against Dr Pullicino must be reassuring for other ‘non-mainstream’ doctors who might reasonably feel more able to become involved in withdrawal-of-treatment cases in the Court of Protection (and the family courts, where similar cases involving children are heard) without fearing for their registrations.

On the positive side, this might lead to a wider range of experts in the courts, which is something Christian Concern has lobbied for, and definitely an issue which needs to be addressed.

Less positively, it may increase the likelihood of what the judiciary has described as “... manipulative litigation tactics designed to frustrate orders that have been made after anxious consideration...”, as Lord Justice Peter Jackson said of the Christian Concern/Christian Legal Centre’s involvement in another case about life-sustaining treatment concerning a child (Indi Gregory).

The fact that the GMC complaint against Dr Pullicino is now closed with no action suggests there may be a very significant discrepancy between the expectations of the judiciary and the expectations of the GMC as regards the conduct of doctors and the use of expert evidence in the courts.

That is bad for patients, bad for doctors, and bad for justice – and it’s a story worthy of The Times.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 500 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and tweets @KitzingerCelia. She can be contacted via openjustice@yahoo.com

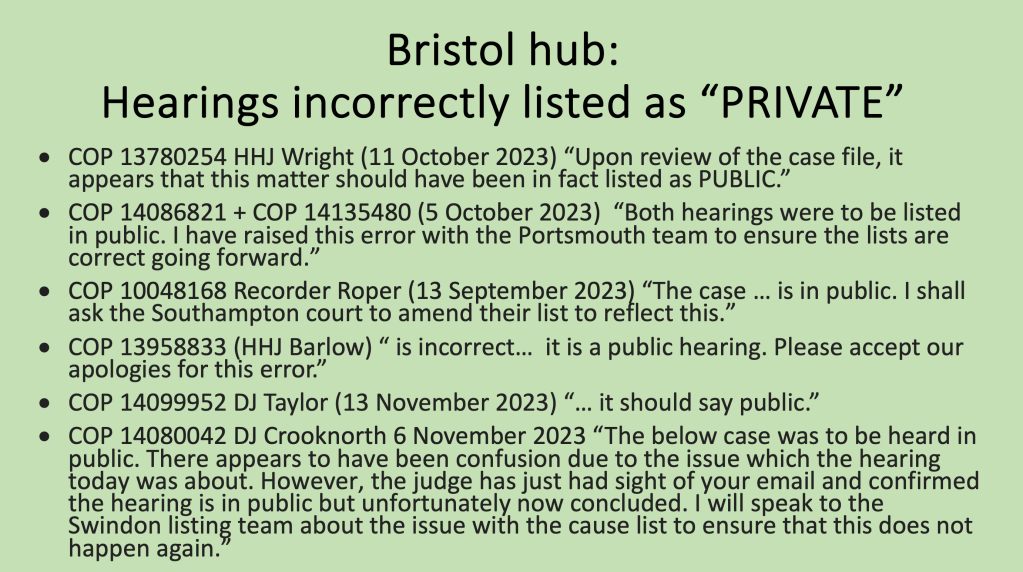

Appendix A

The whole Times article (17 paragraphs) appears in the left-hand column. In the right-hand column I’ve reproduced the source of each paragraph from the Christian Concern press release.

Appendix B: Correction in “The Times”