By Celia Kitzinger, 18th April 2023

The case concerns a 23-year-old woman (“A’), deprived of her liberty in a residential placement against her wishes, who is being given medication, covertly, that she consistently says she doesn’t want.

The court has already made declarations that she lacks capacity to make decisions about residence, care, contact, and medical treatment (as a result of a Mild Learning Disability and Asperger’s Syndrome, plus ‘undue influence’ from her mother). This was based on the report of an independent expert, back in September 2018.

She’s been refusing treatment for primary ovarian failure (also known as primary ovarian insufficiency). The recommended treatment is hormone medication designed to ensure, first, that she goes through puberty, and then to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease and other health conditions associated with this diagnosis. Due to covert medication, she has now gone through puberty, but doctors recommend ongoing ‘maintenance’ treatment for the next thirty years or more.

Every day for two years she’s been offered the prescribed hormone treatment tablet and every day so far, she has declined to take it. That’s more than 700 treatment refusals. Each day, she is then given the medication covertly via her food or drink.

The problem the court, and the professionals caring for her, face now is how to manage the situation long-term. Obviously, she can’t be kept in a care home and covertly medicated for three decades. The question weighing on everyone’s mind is whether and how to tell her that she’s been covertly medicated, and how to persuade her to take the maintenance medication voluntarily.

In an earlier judgment, Mr Justice Poole said that covert medication was “unsustainable in the long run”. He directed that:

“… a treatment plan should be devised, for review by the court, for how to exit the covert medication regime with the least possible harm being caused to A. The plan will cover the question of imparting information to A about the past use of covert medication – should that be done and if so, when, where and by whom….” (§48(iv) Re A (Covert medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44 15 September 2022)

The judge laid out detailed directions as to the work that needed to be done on this in preparation for a hearing in November 2022, but in the event, very little progress had been made by the time of the November hearing. and the judge expressed his disappointment with how little had been achieved.

So, the hearing of 13 March 2023 was primarily concerned with the same thing – what was the plan for telling A about the ongoing covert medication, and how was she to be persuaded to take it voluntarily.

Background

When someone lacks capacity to make their own decision about whether or not to take medication, and they are refusing to take it, and attempts to persuade them have failed, carers are faced with a choice: either abandon the attempt, or hide the medication in the person’s food or drink so that they take it without knowing.

Each case is different. The benefits of medication (or the risks of not taking it) vary depending on what the medication is for and the physical health of the patient. These benefits need to be weighed up against the harm caused by deceiving the patient, and violating their wishes by secretly administering the medication they’ve refused. There are other risks of covert medication too: unknown or variable amounts of medication may be ingested; the person receiving it cannot monitor possible side effects; and there’s also the risk of the patient discovering the pill ground up in the yoghurt or dissolved in the apple juice – and losing all trust in the people who are caring for them.

Covert medication can be lawful if it’s determined to be in the best interests of someone who lacks capacity to make decisions for themselves, and in this case the young woman has been assessed as not being able to understand, retain or weigh the information necessary to make a capacitous decision about medication. (For a lawyer’s view on covert medication, take a look at the blog post by Aswini Weereratne KC.) In this case, it’s lawful because a judge (HHJ Moir) considered the evidence, decided that A lacked capacity in relation to medication, and ruled that covert medication was in A’s best interests – and also that it was in her best interests that she should remain in residential care and have no contact with her mother, who was considered to be a bad influence on her, and that her mother should not be told about the covert medication. It was feared that the mother would tell her daughter about the covert medication, and that she would then stop accepting food and drink from carers.

The judge, HHJ Moir, made these decisions in a secret closed hearing – a hearing that wasn’t open to the public, and that neither the mother, nor the mother’s legal team, knew anything about at the time. The case is now before a different (more senior) judge, Poole J, and is being heard in public.

This has been a long-running and complex case. Observers blogged about hearings we’d watched in May 2020 before covert medication was authorised, and then in April 2022 after covert medication had been authorised but we didn’t know that it had because the court deceived the mother and her legal team into believing that her daughter was not being medicated, and we were deceived too (see “Medical treatment, undue influence and delayed puberty”). In October 2022, we discovered the true facts and published a correction (“Statement from the Open Justice Court of Protection Project concerning an inaccurate and misleading blog post”).

This case has raised challenging issues about covert medication. It’s also highlighted the way in which the Court of Protection can use secret (‘closed’) court hearings to make decisions without family members being present and without them even being told that a hearing is happening – and how this can breach a family member’s rights to a fair trial. We raised the alarm about ‘closed’ hearings when we discovered what had happened in this case, both via our blog post (Reflections on open justice and transparency in the light of Re A (Covert Medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44) and on the Radio 4 Law in Action programme (“Secrecy in the Court of Protection?” 27th October 2022). The matter was then considered by a sub-committee of the Court of Protection Rules Committee (to which I made a submission: Closed Hearings: Submission to the Rules Committee). In February 2023, the (then) Vice President published new Guidance on closed hearings.

Meanwhile, hearings for this young woman continue.

The last hearing was in November 2022 and it felt (as I wrote in my blog post, “No ‘exit plan’) “thoroughly dispiriting”. Despite the efforts of counsel for the Trust (Joseph O’Brien KC) to inject a note of positivity into the proceedings by reminding everyone that the strategy of covert medication and secret hearings had “worked” and been “successful” (in the sense that A has now gone through puberty, which was certainly a key goal), the tone of proceedings felt (to me) rather muted and despondent. The positive aspect (attainment of puberty) has to be weighed against the deception that has been involved and the public opprobrium the case has occasioned.

I was very concerned, as was the judge, that no adequate and agreed exit plan had been put before the court, in line with his directions, at the November hearing. The judge pointed out – as he had previously – that if A were to discover in an unplanned way that she’d been treated without her knowledge and after explicitly refusing treatment, this could be harmful to her: the longer covert medication continues, the longer that risk continues. At the end of the November hearing, it was agreed that there would be a hearing in mid-March at which (the judge said) the court will “review the updated medication plan, its implementation, issues of contact and whether there’s a need for any directions in relation to the residence application”.

The hearing of 13th March 2023

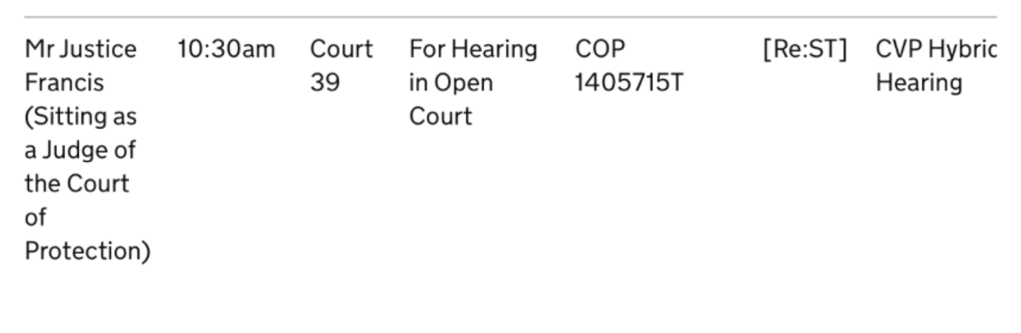

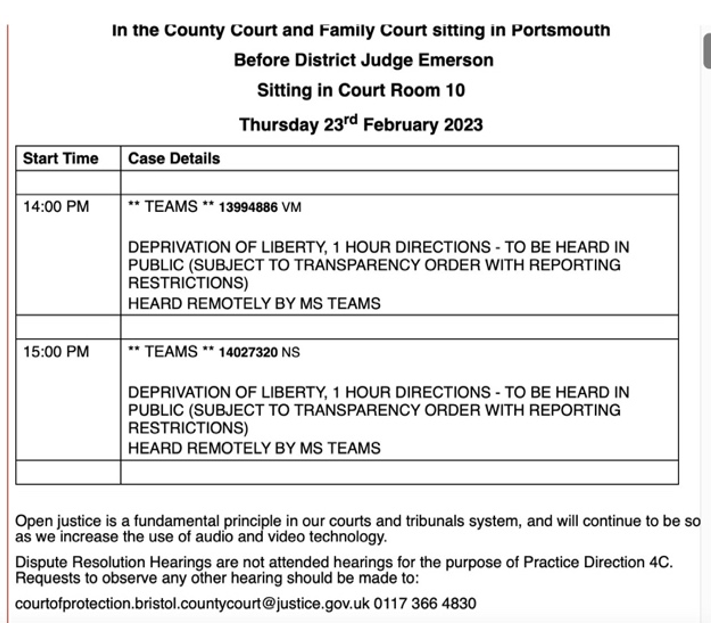

This case (COP 13236134) was heard, remotely, at 10.30am on 13th March 2023 before Mr Justice Poole, sitting in Leeds.

The parties and their representatives were the same as at the previous hearing. The applicant local authority was represented by Jodie James-Stadden. The first respondent, the protected party in this case (“A”), was represented (via her litigation friend the Official Solicitor) by Sam Karim KC. The second respondent was A’s mother, represented by Mike O’Brien KC. The third respondent was the hospital trust, represented by Joseph O’Brien KC.

A key part of this hearing was supposed to be a review of the updated plan for moving from the current position in which A is being given involuntary covert medication, to the ideal position in which A voluntarily agrees to take medication. Some work had been done on this plan during February – but 10 days before the hearing (on 3rd March 2023), the situation suddenly changed. Staff conducting an ‘educational’ session with A informed her that she had reached puberty. This hadn’t been anticipated in the plan, so it’s back to the drawing board to determine how the plan should now be developed. There is an additional problem now in that A seems to believe that, as she has gone through puberty ‘naturally’ (she has no reason to believe otherwise), she does not have Primary Ovarian Failure (POF). The Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) “is now required to decipher how to overcome A’s resistance in accepting the diagnosis of POF” – and with it, the need for continued endocrine treatment (Official Solicitor’s Position Statement).

Instead of reviewing an updated plan, the hearing covered a number of issues that I’ll deal with separately: (1) transparency matters; (2) the unplanned disclosure to A that she’s gone through puberty; (3) expert reassessment of A’s capacity and related issues; (4) contact between mother and daughter; (5) permission to appeal out of time against earlier decisions by HHJ Moir.

1. Transparency Matters

I almost didn’t get to observe this hearing because it hadn’t been listed properly. This is a repeated problem when Tier 3 judges (who usually hear cases in the Royal Courts of Justice in London) sit in other courts across England and Wales. These hearings are not included in the Royal Courts of Justice cause list (which is where we normally find Tier 3 judges’ hearings) but are supposed instead to be listed in the Court of Protection list in CourtServe – which is the only way for members of the public to find out about court hearings outside of London. They are often not there. I’ve blogged about the problem previously (e.g. here) and raised it with the (former) Vice President and with His Majesty’s Courts and Tribunal Service (HMCTS). I’ve also written previously to Poole J about this very problem when it affected a different hearing before him.

Poole J opened the hearing by stating that it had been “noteworthy, given the history of the case” that he’d not received any observer requests and that he’d learnt it was “because of the way it’s listed”, which he described as “an unsatisfactory situation” that occurs “regularly” and “needs to be remedied”. I’m very pleased (finally!) to see a judge take listing problems seriously and hope communication with HMCTS from Poole J might be more successful than my communications with them in effecting change. I only found out about the hearing when the judge’s clerk emailed me shortly beforehand to let me know it was happening, and I was able to drop everything and attend. (I think the judge also delayed the start of the hearing by 45 minutes to allow me to be there from the beginning.) I’m very grateful to Mr Justice Poole for supporting open justice in this way – but of course it shouldn’t be necessary – and other members of the public who wanted to observe hearings in this case were excluded because it wasn’t listed correctly.

I also note that there continues to be a draconian set of reporting restrictions relating to this hearing. In addition to the usual restrictions on identifying the protected party at the centre of the case, and her family members, we are prohibited from identifying the public bodies (the local authority and NHS Trust) and the expert witness (Transparency Order signed by Mr Justice Poole, dated 15th September 2022).

2. Unplanned disclosure to A that she’s gone through puberty

Counsel for the local authority said that the plan had been that A was not to be told that she’d achieved puberty “and if she raised questions that was to be taken back to the MDT for responses to be formulated”. Now that – contrary to the plan – she has been told she’s gone through puberty, “there needs to be an urgent MDT to revisit the plan”. Meanwhile, everyone agrees (said counsel) that the maintenance medication should continue to be given covertly while the MDT works out “what narrative she is going to be told”.

“At the moment, there’s a confusing narrative before her, as she’s been told she has POI and that without taking the medications – the medications she’s been offered and refused daily – she would not experience puberty. Now she’s been told that while she still has POI, she has experienced puberty – and she’s gone through puberty without taking medication, as far as she’s concerned. That is a difficult and inconsistent position to be in. The MDT needs to reconsider the plan and come up with a coherent explanation to help P make sense of what is happening to her.” (Counsel for the local authority)

The mother’s Position Statement describes what happened in more detail.

“At a session on 3 March 2023, A suggested to health staff that she had breasts and that she had therefore reached puberty. A therefore now knows she has reached puberty. Staff implied it had occurred naturally in order to keep the covert medication secret from her. They said she continued to need to take the medication for her heart and bones. It looks like A was left with the impression that she had achieved puberty naturally but late and therefore she seemed to think she did not have Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (‘POI’ or ‘POF’).”

The Position Statement goes on to quote from an email from the local authority’s solicitor describing what was reported to him about the conversation with A. Apparently during the course of a health education session involving a talking mat, A was asked what Primary Ovarian Failure was and placed the response “a ladies breast will grow” (sic) under the “don’t know/depends” category. She was then informed that “if you have POF breasts won’t grow” and “immediately questioned this as she stated I have breasts”. Asked whether she thoughts she had gone through puberty, A said, “I’ve not given it a thought, but subconsciously thought I had. But I don’t have the problem [i.e. POF]”. When told she does have a diagnosis of POF, “she continues to fail to accept the diagnosis”. One of the professionals working with her explained that she’d gone through puberty later than other girls and explained that a review of her medical records confirms the diagnosis, to which A said, “You are going to say something completely different to what I’ve said in an extremely long-winded way”.

Her mother is concerned that A has been told that puberty happened naturally but late, and consequently thinks she has not got POI and does not need medication to deal with it. She’s also worried that A will guess that she’s been covertly medicated. She wants to be involved in explaining to A why she should (voluntarily) take the maintenance medication, and believes that she would be able to persuade her – whereas professionals have failed to over the last four years. She’s currently forbidden to talk to A about medication issues. This is because the MDT members distrust A’s mother, and don’t believe she really wants A to take the medication. The Trust “continues to have some concerns as to whether [the mother’s] wish to support A in taking the maintenance medication reflects a genuine recognition and acceptance on her part that such medication is life sustaining and enhancing for A” (from the Trust Position Statement).

In court, Counsel for the mother described “an incident on Friday where A confronted her mother about the fact that she’s reached puberty”. He said:

“[Mother] had been picked up in a bus with two care staff and A joined them. She turned to her mother and said she’d been told she’d achieved puberty and she was wondering why, then, she was still detained and whether she could come home. [Her mother] realised that carers had reacted in some alarm, and said ‘what can I say?’. Carers then cut off the discussion and [the mother] changed the conversation to what they were doing next. So this signals that A is well aware of the implications of having achieved puberty, and her mother is concerned about this.”

He added that the concept of covert medication is not new to A and that – at some time in the past – she had avoided drinks that could have been tampered with in this way and insisted on bottled water.

The judge intervened to say simply (as he has said before) that “covert medication cannot continue for ever. It is not sustainable in the long term. It is best that it should come to an end in a managed way.”

Counsel for the Trust was also concerned that “A believing that she has gone through puberty without medication may lead her to become entrenched in her position that she does not need maintenance medication”. Despite concerns about the mother’s involvement, he accepted that she did now need to be involved in the collective effort to “get A on side in terms of taking medication voluntarily”.

The Official Solicitor (appointed to represent A’s best interests) now believes that the mother “must be intrinsically involved, and be at the forefront, of any plan that seeks to promote A accepting the diagnosis of POF and the need for treatment… Her positive involvement is of magnetic importance”.

So, the matter of the revised plan (with the mother centrally involved) will return at the next hearing.

In the closing judgment, Poole J said that the situation needed to be handled both with urgency and with delicacy, sensitivity and professionalism. He directed that there should be an MDT meeting and then a round table meeting with the legal representatives from all parties with a focus on communication with A and formulation of involvement of the mother. “The ideal outcome is that A will accept maintenance medication in a sustained way for the rest of her life. That will be achieved most easily – or most effectively, I should say, not easily! – in full knowledge of the truth. The worst outcome is that she finds out inadvertently and reacts with hostility. I leave it for the professionals to work it out and the plan will be reviewed by me in four to six weeks from now.”

(3) Expert reassessment of A’s capacity and related issues

The impetus for reassessment of A’s capacity (in all the relevant domains) came from the Official Solicitor. It was motivated, in part, by the independent expert’s observation (back in September 2018) that “A may gain capacity having regard to her young age, and if a range of support structures are in place to empower A, including increasing her skill-base and knowledge”. The expert also said that “achieving puberty may improve cognitive maturation and help her to gain capacity”. An independent expert could also be asked to consider related issues e.g. the likely consequences of A being informed that she’s been covertly medicated, why she’s resistant to treatment, and what can be done to change her mind.

Counsel for the local authority said they were neutral on the subject of an expert being appointed, but were “not convinced that further professionals are going to assist in the mix”. The local authority has “some concern with overwhelming A with professionals, as she is quite resistant”. However, if there is to be appointment of an expert, then they are in favour of appointing the same one as last time.

Counsel for the mother said there were fears that A would not cooperate with the previous expert and that “a new set of eyes” were more likely to elicit her cooperation. The mother would also like the expert appointed to assess the effects on A of a four-year separation from her family.

The Trust took the position that this was an appropriate time to revisit capacity because “the current evidence is quite old” and “puberty may be relevant to her cognitive functioning”; and that there are compelling reasons for appointing the same expert as previously because “he knows the background; he is aware of the relationship between mother and daughter; he knows where to tread delicately. There are considerable dangers in inviting another expert without that knowledge and experience”. This seemed to resonate with the judge who said he “wouldn’t want the involvement of an expert assessing capacity and having to discuss issues of medication with A at this delicate time to interfere with the MDT process of deciding what information should be imparted and how. “This sounds disrespectful but (laughs), I don’t want an expert crashing in, as it were, on this delicate process”. With the previous expert, it seems, that is “less likely to happen”. Counsel also said that the Trust “don’t see the point of asking the expert to look at the impact of four years separation from her family – that’s not relevant to capacity or to the medication plan”.

In the closing judgment, Poole J said that he had to be satisfied that it was “necessary” before appointing an expert to give further evidence. “On the issue of capacity, I am persuaded it’s necessary. She’s achieved puberty and it was foreseen in earlier expert evidence that changes and maturation of the brain with puberty may impact on her capacity. I am not persuaded that the other issues floated need to be revisited but an assessment of capacity, especially in relation to residence, care and treatment, is necessary. As to the identity of the expert, Mr Mike O’Brien says on behalf of the mother that A distrusts the expert who saw her last time, but he has knowledge of the context and there is a benefit to continuity. The qualification is that he should not meet A until after the next hearing. Priority should now be given to providing information for A. I am a little fearful that involvement of an expert, even [the same one as last time], at the same time as that process is ongoing could disrupt it inadvertently.”

4. Contact between mother and daughter

Current contact arrangements are two half-hour supervised telephone calls a week, and supervised weekly face-to-face visit of one hour, with discretion to extend that up to two hours. Contact has generally gone well, and the mother would like to increase the weekly visit for up to three hours. She also wants A to be able to attend her grandfather’s funeral.

Counsel for the local authority said they do not recommend any changes to the contact arrangements because “the focus should be on enhancing the health promotional work, and there shouldn’t be additional distractions to A at the present time. She has an awful lot going on at the moment. She’s been informed she’s gone through puberty. Her grandfather passed away a week ago, and there’s the suggestion of additional experts. So, the local authority would prefer to restrict contact to up to two hours and review this in four to six weeks.”

Counsel for the mother said that in fact contact has never been two hours: “the longest visit has been an hour and a half”. He drew attention to the Official Solicitor’s view that the mother’s involvement in persuading A to agree to maintenance medication is of “magnetic importance” and said that longer visits would make it more likely that the mother can fulfil this role. “[Mother] knows A can be stubborn and difficult, particularly about professional advice. It may take her a bit of time, but she thinks she can persuade her.”

In the closing judgment, Poole J reflected on the fact that contact has gone well. “There’s no evidence that [A’s mother] has given inappropriate information. This is a suitable time for contact to be extended to supervised face-to-face contact once a week for up to three hours. Arrangements should also be made for A to attend her grandfather’s funeral.”

(5) Permission to appeal out of time against earlier decisions by HHJ Moir

Counsel for the mother asked for permission to appeal against the decisions made by HHJ Moir in the closed hearing of 25th September 2020, from which the mother and her legal team were excluded. He set out detailed reasons why permission should be granted. The judge did not grant permission and gave a full and separate judgment giving his reasons for not granting permission to file an appeal. A transcript of Poole J’s decision will be made available to the parties and (the judge has said) to me when it is ready. I will blog separately about this aspect of the hearing when I have received the transcript and can be sure that I am entirely accurate in reporting the reasons for the judge’s decision.

Concluding remarks

In his closing judgment, Poole J effectively pursued the same line of reasoning as in previous hearings. He remains concerned that A might realise that she has been covertly medicated and lose all further trust in professionals. He wants a plan as to how she is to be told about the covert medication and an ‘exit plan’ to enable a move from covert to voluntary medication. He continues to request this of the MDT, which has so far failed to provide an adequate (and agreed) plan despite this having been requested since November 2022 – and subsequent events have overtaken the draft ‘exit plan’ they had expected to present to the court. He’s also increased face-to-face contact between mother and daughter, which is surely necessary given the central role the mother is now envisaged as having in implementing the ‘exit plan’ with her daughter. Meanwhile, covert medication remains in place, as does A’s deprivation of liberty which the judge considers “necessary, proportionate and in her best interests”. The question of where A will live “will be considered once there’s more clarity on the use of medications and communications with A”.

It seems to me that the court is now in the unenviable position of trying to help the MDT extricate itself from the entirely untenable situation it’s in following the directions of HHJ Moir. I am left wondering how everyone thought this would be brought to a satisfactory conclusion. What ‘exit plan’ was envisaged at the point the judge set the wheels in motion for covert medication? Nobody can have imagined that A could be detained and covertly medicated for the next 30 years – but nobody seems to have planned for any alternative.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She’s personally observed more than 420 hearings. You can follow her on Twitter @KitzingerCelia