By Celia Kitzinger and Claire Martin, 2nd May 2022

IMPORTANT NOTE: We accept, with regret that this blog post is inaccurate and misleading.

Please see our updating “Statement” of 11th October 2022

The protected party at the centre of the case is a woman in her early twenties who has not experienced puberty, because she has not been provided with the recommended medical treatment for her “primary ovarian failure”.

She has diagnoses of “mild learning disability” and “autism spectrum disorder, namely Asperger’s syndrome” which cause her to lack capacity to make her own medical decisions. (She also has epilepsy and – at least at the start of the court case – had a vitamin D deficiency).

She was removed from her mother’s care in April 2019 and placed in a care home in order to ensure that she receives appropriate medical treatment which the local authority says her mother is preventing her from having by dint of exerting control and undue influence over P. (Her mother denies this.)

The treatment focus for the court is particularly on P’s primary ovarian failure. Without treatment, they say, there are significant health risks, including premature death (see: “Primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young women”; “What are the treatments for premature ovarian insufficiency?”).

There was mention at some point during the hearing that someone from the Turner Syndrome Support Society had visited P and discussed treatment for pubertal induction with her. The website has very useful information (some of it written for girls and young women) about oestrogen treatment and how to manage it.

Back in May 2020, the Official Solicitor stated unequivocally that treatment “should commence as soon as practicable and without further delay”.

However, it seems that since the court authorised removing her to the care home more than three years ago, P has not been treated for her primary ovarian failure.

It is entirely unclear to us why she has been left untreated, since this was a key justification for depriving her of her liberty in the care home (against her will, and that of her mother) and for restricting and then stopping contact between mother and daughter.

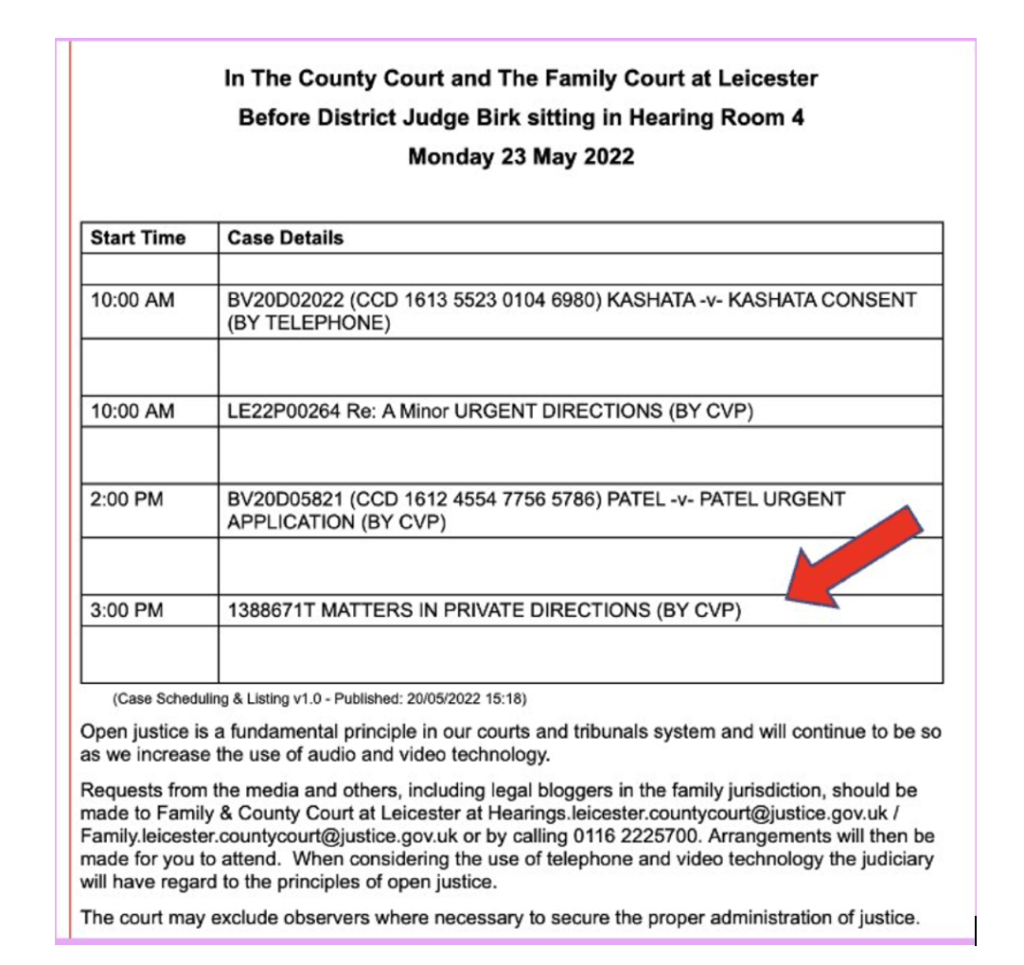

We have observed two hearings in this case (COP 13236134), both before Her Honour Judge Moir. We know there have been many other hearings as well. The first hearing we observed was on 26th May 2020 (observed by Celia Kitzinger). The second was on 25thand 29th April 2022 (observed by Claire Martin). When we shared information with each other about the hearings we’d (separately) observed, we were surprised, and dismayed, by the apparent lack of progress over this 23-month period.

We’ll provide some background information (based on a Case Summary, helpfully provided by counsel at the hearing on 26th May 2020) and then each of us will give an account of the hearing she observed [1].

We are “baffled” (as the title of this blog post conveys) because it was absolutely clear at the hearing in May 2020 that the local authority, P’s social worker and P’s endocrinologist were strongly committed to ensuring that P should receive endocrine treatment, and this was endorsed by the Trust and by the Official Solicitor. Although we haven’t seen the judgment, we’re almost certain that this must also have been the conclusion reached by the judge.

Medical treatment was, as the social worker put it in May 2020, the “bigger concern” that weighed against P’s (and her mother’s) Article 8 rights to family life. It justified not only removing P from her home but also instituting a total ban on contact between mother and daughter for a six-month period.

But nearly two years later, it seems that endocrine treatment has not been given, and there is discussion of P returning to her family home – either with or without her mother in residence there too – in the hope that (after all this!) her mother will then be able to persuade her to have it.

There will be another hearing in this case, this time before a Tier 3 judge in the Royal Courts of Justice, in June or July 2022. We hope to be able to observe it, and perhaps matters will become clearer for us then. We are left with many questions and uncertainties about the case at the moment.

Background: The court’s decision of 18th June 2019

P lived at home with her mother until 9th April 2019 when she was conveyed to a residential placement following an interim authorisation by the Court.

The local authority had started legal proceedings in the Court of Protection following two safeguarding alerts raised by the NHS on P’s admission to hospital having suffered epileptic seizures on 13th September 2017. Hospital staff had noticed that P had not undergone puberty and reported that P’s mother appeared to exert a domineering influence over her.

Final judgment regarding her place of residence, deprivation of liberty and care and treatment, was handed down on 18th June 2019. (Neither of us observed this hearing).

Based on the evidence before it, the court made findings including that:

- P lacks capacity to conduct proceedings and to make decisions about where she should reside, about her care and support needs, about her medical treatment and about her contact with others

- P has a diagnosis of primary ovarian failure, the treatment for which is sex hormone replacement therapy

- Receiving the treatment would have no adverse impact on P

- Without treatment, the long-term prognosis for P is “extremely bleak” – with an increased risk of osteoporosis, facture risk and an increased risk of premature death through stroke and cardiovascular disease.

- P’s mother was not accepting of this medical advice, continuing to press for a second opinion, despite the evidence being that there is no range of medical opinion on this issue

- The court could have no confidence that P’s mother would encourage or support P to take the requisite medication or to keep hospital appointments

- P’s mother preferred P not to ‘grow up’ and to remain instead dependent on her and isolated without any outside influence or interference

- P’s mother exhibited no motivation to support P to develop a sense of identity separate from her and showed no inclination to assist P to achieve any growing independence

- P’s mother was resistant to the idea that P should progress, cease to be like a young girl, or achieve any independence

- The court had no confidence that P’s mother would facilitate and support any care or treatment plan.

By order of 18 June 2019, the court made final declarations that P lacked capacity to make all the relevant decisions and that it was in her best interests to reside at Placement A and to receive care and support, including treatment for her epilepsy, her ovarian failure and her vitamin D deficiency. It was also declared in P’s best interests to have supervised contact with her mother and her grandparents, and a schedule of contact was appended to the order.

At a review hearing on 17th December 2019 that contact was reduced. Contact was still to be supervised and to cover only approved topics of conversation.

Hearing on 26th May 2020, by Celia Kitzinger

The hearing I watched (remotely) on 26th May 2020, before Her Honour Judge Moir sitting in Newcastle, was listed as a review hearing. I wrote a brief summary of the case shortly afterwards in this blog post for The Transparency Project. Here I’m writing a fuller account based on contemporaneous notes from the hearing.

By the time of the hearing, P had been living at Placement A for about a year – and my understanding is that this is some geographical distance from her family home.

During her time at Placement A, there had been a “significant decline” in P’s engagement with her epilepsy treatment and she had not attended any appointments with her endocrinologist. She was not receiving sex hormone replacement therapy.

The court was informed that she also has “low mood” (which all therapeutic options so far have failed to ameliorate). She neglects her personal hygiene, intermittently refuses to eat and drink, and is refusing to engage in any social activities and is spending increasing time in her room.

The local authority (with the support of P’s social worker, P’s epilepsy clinician and P’s endocrinology clinician) was seeking a further order by which all contact between P and her mother was to be suspended for an initial six-month period. This is said to be “essential for P’s physical, emotional and social wellbeing”. Contact between P and her grandparents could be maintained (twice a week) but subject to supervision.

During this six-month period, it was proposed that there would be ongoing MDT consultation reviews to monitor and review any health and welfare concerns.

The Official Solicitor and Trust were both broadly supportive of that position.

P’s mother opposed it. She wanted P to return home.

Most of the full-day hearing was occupied with hearing from two witnesses: P’s social worker, and P’s mother. Here is a flavour of the oral evidence from each of them

1. Social Worker

The social worker was cross-examined by counsel for P’s mother, counsel for the NHS Trust and counsel for P via the Official solicitor. I have selected some salient extracts from each cross-examination. Her core position was that P’s mother has “hindered” P’s engagement with staff seeking to support her with endocrine treatment and that cessation of all contact between mother and daughter for a six-month period was essential. According to the case summary I was sent, P is refusing to engage with her social worker, “pulling her bedclothes over her head and/or pretending to be asleep when she visits”.

Counsel for P’s Mother (Natalia Levine)

Levine: It seems to me that the local authority has been quite quick to assume wrong-doing of family members rather than seeing the problem as lying with the placement and restriction of contact. P wants to return home, doesn’t she?

SW: Yes. But she doesn’t understand the full range of issues that led her to be conveyed to Placement A.

Levine: She’s been nearly a year now at Placement A.

SW: Yes. We’ve been trying to engage with her the best way we can, but it’s been trial and error. It takes time. Contact with [P’s mother] has sometimes hindered the approaches that staff have tried to take.

Levine: Right, but what has happened in real terms is that P’s presentation has deteriorated.

SW: Yes. There have been concerns about self-care and neglect. We are trying to address them with health education and communication.

Levine: The amount of contact she is able to enjoy with family members has decreased since April last year and she has also deteriorated over that time.

SW: We’ve stuck to the schedule of agreement.

Levine: She’s having less contact with her family, and her condition has deteriorated.

SW: Yes, but there are small pockets of progress. She will engage with some staff quite positively.

Levine: The order sought is a huge infringement of P’s Article 8 right to family life.

SW: P has a right to a long and healthy life in her own right.

Levine: Does it ever cross your mind that the problem is not the family but the placement?

SW: The placement provides opportunities for P and a well-informed community team.

Levine: Do you not agree that just because a placement on paper looks like it can meet the needs of someone, that doesn’t mean it can do so in practice?

SW: I get what you’re saying, but the risks of returning P home outweigh the benefits.

Levine: As I see it, there’s a breakdown in trust between P and some of the staff members.

SW: Unfortunately, those incidents have occurred because of [Mother’s] involvement and influence.

Levine: Do you not think that if a placement was found closer to where P was originally from, it might open up the opportunity for her friends to visit.

SW: There’s a paucity of specialist residential facilities (goes on to explain)

Levine: P does feel isolated due to geography – that should be a huge incentive to explore alternative placements, and also the difficulties with staff members.

SW: A new placement wouldn’t solve the issues with the family. It wouldn’t change the dynamics that any staff team would have with [Mother].

//

Levine: Has P had any contact with individual friends?

SW: No, she didn’t want to engage with that at all. Some effort was made […] but [Mother] has been reluctant to provide information about P’s friends to staff.

//

Levine: (If the no-contact order is approved) are you going to return to court to reinstate contact if P continues to deteriorate, or what?

SW: We accept that P will be upset at a no-contact position, but we have to prioritise a long-term health condition, so we would expect a six-month review.

Levine: You have a 21-year-old whose presentation has deteriorated over the last 12 months and you say, ‘we’ll have a six-month review and we’ll monitor it”. If she stops eating and drinking as much as she is now, and refuses medication, what are you as a local authority going to do about it?

SW: Our bigger concern is her longer-term health. It’s not about ignoring those issues. It’s about working with P to support her. Her going home, or to another placement, won’t address the bigger issue of her not accessing the endocrine treatment.

Levine: Who is going to tell P about the order of the court today?

SW: Normally that would fall to me, but as she’s not engaging with me that could be someone else. If she doesn’t choose to speak to me, it will be others in the community team.

Levine: What is she going to be told?

SW: We’ll prepare some easy-read information and think about the most person-centred way of dealing with this.

(This segued in a discussion of the COVID-19 restrictions – which were quite new at this point: there was mention that they “could last until Christmas”.)

//

Counsel for the NHS Trust (Joseph O’Brien QC)

O’Brien: When the court gave a judgment in June last year, Her Honour found that [Mother’s] interaction with P was stifling her opportunities to experience quality of life. Have you seen anything to support that [Mother] has taken those words to heart and changed her behaviour at all?

SW: No. There have been only two occasions when she’s worked with staff to support P: one to help her agree to washing her hair, another time to facilitate her taking medication. It’s the exception rather than the rule.

//

O’Brien: Is it right that contact is used as an opportunity for [Mother] to influence P. (Reads out message from Mother to P from Para. 41 of the records): “I love you P and you are beautiful. Don’t let them break you. Stay strong and don’t let them tell you what to do”.

SW: Yes, that’s a bit of a concern. There’s a statement there to tell P not to work with staff.

//

O’Brien: In February of this year, you were of the view that contact should remain as it is and you were worried about the serious impact that terminating or suspending impact between [Mother] and P would have on P. But the passage of time has convinced you that the balance of evidence has shifted.

SW: Yes.

O’Brien: It’s significant in your view that P should engage in endocrine treatment that is valuable to her quality of life. When you look at the balance sheet of probability, do you believe that endocrine treatment is more likely to take place with [Mother] continuing to have contact with P or not.

SW: It’s less likely if [Mother] has contact.

Counsel for P via the Official Solicitor (Sam Karim QC)

OS: How is P at the moment? You say she’s not eaten for a while and her fluid intake is not good and that she hasn’t changed her clothes for a while.

SW: Since that statement she has been eating and drinking – but I don’t believe she’s showered or changed her clothes.

OS: What steps have you taken?

SW: We’ve provided easy read reminders of self-care – it’s as I said a bit of a trial-and-error approach.

OS: How long has this been happening?

SW: It’s been happening the last 9-10 weeks, but prior to that there have been earlier periods when she’s done this.

OS: What do you think is the cause?

SW: A range of factors. Her mood. Contact with [Mother].

Asked about restrictions on visits by P’s grandparents, the SW said this too was “so they don’t undermine the care team with negative comments about the professionals”.

2. Mother

P’s mother said it would be “cruel” to stop contact between her and her daughter. She maintained that she had assisted staff to encourage P to take medication (contrary evidence was read out in the form of a message from mother to daughter saying “don’t let them tell you what to do”). She believes P has capacity to make her own decisions (including about medication and sharing information with staff. Her statement that if her daughter had been at home, she’d have been taking the endocrine treatment by now was a “surprise” to the court because (said counsel for the Trust) it had appeared that the mother herself opposed endocrine treatment without a second opinion from another expert. The mother’s explanation that the second opinion was (and had always been) part of an attempt to persuade her daughter to take the medication that she herself was already convinced her daughter needed was treated with considerable scepticism by counsel for the Trust, whose cross-examination of the P’s mother was characteristically robust.

Counsel for P’s Mother (Natalia Levine)

Levine: You know that the local authority application is to restrict your contact with your daughter so you would have no contact with her at least for six months.

Mother: I disagree with it strongly. It’s cruel. It will have a devastating effect on my family, particularly my daughter. Restricted contact has made my daughter retreat to her bed and become seriously depressed. She’s become more depressed and withdrawn.

P’s mother gave examples of times when the care home had contacted her for assistance to persuade P to take medication (“and she took the medication within 5 minutes and they’d been trying for hours and hours”), and she described saying to P, “why don’t you have a bath, why don’t you freshen up?”.

P’s mother was very clear that she wanted her daughter back home, where “she saw her grandparents every other day, she was always outdoors, she was happy, she had her dancing” and was able to see her friends.

She said: “You’ve all had my daughter in care for over a year now, and all that it’s done is she’s depressed. I’m sure you didn’t intend for her to be locked up, but she is. The less she’s seen of us the more it’s damaged her – and the depression went along with that”.

Ps mother also stated her belief that P would take sex hormones (“medication for her development”) if she were able to come home: “That should have been sorted. This has all prevented her taking that medication. My daughter is a maternal sort of girl. She’s already lost that year of taking these tablets. She could have been taking these for a whole year, if she’d been at home”.

Local Authority (Jodie James-Stadden)

Stadden: You would say, would you not, that P’s decision not to go to medical appointments and not to get showered or change her clothes – those are decisions she has made for herself?

Mother: I think they are a result of her circumstances. (Cites P’s “depression and general unhappiness”; and P’s neglect of personal hygiene is because she dislikes “people peeking in on her in the shower”). It’s not the case she’s made a conscious decision. She’s worked out a way to cope with the misery that she’s in.

Stadden: Your counsel says you remain of the view that your daughter has full capacity to make decisions for herself?

Mother: Yes.

Stadden: You still reject the decision that Her Honour made last year that your daughter does not have capacity?

Mother: I think my daughter has capacity.

Stadden: And you are adamant that your daughter’s behaviour at the placement has nothing to do with you at all.

Mother: Absolutely not. My daughter has started to repeat bad language and she’s become more inward. This is not my daughter – she’s usually happy and free-spirited.

Stadden: Isn’t the truth of the matter, Mrs P, that throughout the time your daughter has been at this placement that you’ve tried to undermine the staff in their efforts to engage her.

Mother: Absolutely not. I’ve tried to work alongside the staff. I’ve offered information about her dancing and I’ve offered to take her dancing shoes down, but she has decided she doesn’t want to do that.

Stadden: But you heard [the social worker] say earlier that you have shown a marked reluctance to give staff details of your daughter’s friends.

Mother: I reject that. I asked my daughter, “is it okay if I give staff your friends’ details?” and she said, “no, absolutely not”. She’s 21 years old and I think it’s up to her as an adult whether she gives those details out.

Stadden: So you’re saying the only reason you haven’t given those details out is because your daughter told you not to.

Mother: Absolutely.

Stadden: Part of the reason for your daughter being in her current placement is to encourage her to be more socially integrated and less isolated.

Mother: Of course.

Stadden: Why haven’t you then encouraged your daughter to give details of her friends to members of the staff to promote her building on those friendships and becoming more socialised?

Mother: I think it’s very unfair of you to say that. I’ve spoken about this many times with my daughter. I have encouraged it. I do want my daughter to be more sociable.

Stadden: There are no records of you saying ‘come on then, let me give them X’s phone number’.

(Mother says she’s mentioned it several times)

//

Stadden: There’s been no progress with treating P for primary ovarian failure since she’s been in this placement.

Mother: Exactly! And if she were at home she’d have had it.

Stadden: There’s no evidence of you ever having positively encouraged your daughter.

Mother: Yes I have! I’ve always told my daughter, ‘take all of your medication’. Why is everyone saying everything negative about me when I’m her mother, and I love her.

//

Stadden: You say you’ve done your best to get your daughter to engage, but there’s no evidence in terms of telephone records of that – but there are notes saying you’ve tried to undermine your daughter’s placement. For example, telling your daughter the staff were breaking the law by not allowing her to have contact with you when she wants.

Mother: I think I said she was entitled to two telephone calls.

Stadden: There are other things you’ve said and done that aren’t permitted by the contact schedule, but you’ve gone ahead. Like the diary.

Mother: Yes, let’s discuss the diary please.

Stadden: ‘Don’t let them tell you what to do’ – now, that’s not encouraging your daughter to engage and comply with the staff, is it?

Mother: It was all meant to boost my daughter’s morale. Usually, she’s so free-spirited and happy. It was all meant in a positive way.

Stadden: How is ‘don’t let them tell you what to do’ a positive comment to your daughter?

Mother: Because it’s good when my daughter makes up her own mind.

Stadden: The contact schedule says not to undermine – by action, words or comments – the care staff or the approach they take to her. Surely that comment is undermining?

Mother: By ‘them’ I meant ‘anybody’. Why would you take it I meant ‘staff’?

Stadden: The schedule also says you shall not raise or discuss with her returning to live with you. Yet you just recently said to her, haven’t you, that you’re trying to get her home.

Mother: She’s so depressed. What’s wrong with her coming home?

Counsel for the NHS Trust (Joseph O’Brien QC)

Counsel for the Trust focussed on statements the mother had made – apparently for the first time in the course of this hearing – about accepting the need for her daughter to have endocrine treatment. “Everyone who has been involved in this case,” he said, “may be as surprised as I am to hear that you now think this treatment is essential for your daughter.”

P’s mother said this had always been her view. Her previous insistence on a second opinion was not, she said, because she herself doubted the need for her daughter to have endocrine treatment, but because P did.

“It was that my daughter needed to hear it from someone else… I knew it was essential. It was about what was the best way to convince P, nicely, and sugar-coated, to take the treatment, and not in a negative or psychologically and emotionally distressing way.” (Mother)

Joseph O’Brien read out a passage from the previous judgment to the effect that P’s Mother “does not accept” the expertise of the treating clinician who had recommended the treatment, and asked, “are you saying the judge misunderstood you?”.

Mother: I think I was misunderstood, yes.

O’Brien: When did you realise you had been completely misunderstood by everyone in that court? […] You are making up all of this in order to support a return home, and you do not believe your daughter needs this treatment. This is a ploy by you, Mrs P, to try to persuade people that you believe this treatment is necessary in order to get your daughter home. You know that is not what you believe. What have you done by way of contacting Dr A and asking “Doctor, how can I progress this treatment for my daughter?”

Mother: I object. I haven’t contacted Dr A but we do have letters with appointments for my daughter to go.

O’Brien: No, this is the way for you to get her home, so she doesn’t have this treatment. Okay – what about this. How about arranging an appointment at SH?

Mother: Why do we have to go to SH?

(O’Brien leans back in his chair, closes his eyes, and shakes his head from side to side in a display of incredulity)

O’Brien: Why, oh why, oh why can you not see that that would be the way forward?

//

O’Brien: Why has it taken you until now to tell us that the premise of this case and the premise of the judge’s findings were completely wrong?

Mother: I think I told my solicitor.

O’Brien: You’re making this up, aren’t you?

Mother: No, I am not.

O’Brien: You are fabricating a story that – on any basis of the judgment given last year – this treatment is not necessary until I get a second opinion that tells me it’s necessary.

Mother: That’s not true. I object.

O’Brien: So serious is your suggestion now that you have been misunderstood completely, that this shows a level of deviousness that you cannot be trusted in terms of contact. […] I am going to give you again the opportunity of accepting that your position last year was that treatment wasn’t necessary, without a second opinion.

The judge intervened.

Judge: When did you reach the opinion the endocrine treatment was necessary for your daughter?

Mother: I’ve known the treatment was necessary. It was just the most sugar-coated way of getting her to accept this.

Judge: Why has a year gone past when you’ve not sat her down and told her she needs the treatment. You’re her mother – why have you not made the effort?

Mother: P’s attitude is ‘I don’t want to talk about it’. And also the very limited contact time. There’s so much P wants to say and wants to get off her chest.

Official Solicitor (Sam Karim QC)

Karim: The independent expert said that P has a mild learning disability and Asperger’s. Do you accept those diagnoses?

Mother: No, because we have two psychological reports that say otherwise, including one who knows P well – and he’s older and has kids himself.

Karim: Last year you said one of the reasons you wanted a second opinion was because of lies. Is that still true.

Mother: I don’t know why Dr A said that P had no uterus and no ovaries. The fact is that she does have these parts that Dr A said she didn’t. This was the most distressing thing to my daughter. You can understand why this would be so distressing to a girl of that age, and family is paramount and she is very maternal.

//

Karim: You gave a view about why you think P is not taking the medication in relation to epilepsy.

Mother: I don’t know why she’s not taking the medication for epilepsy.

Karim: “You are beautiful. Don’t let them break you. Stay strong and don’t let them tell you what to do”. What does that mean?

Mother: I just meant what I said before, to boost my daughter’s confidence to be her own self and make her own mind up.

At which point the judge intervened:

Judge: What does, “don’t let them break you” mean?

Mother: We knew how depressed she was. It meant, “don’t let them get you down”

Judge: “Don’t let them get you down” and “don’t let them break you” are two different things aren’t they.

Closing submissions

For the local authority, Jodie James-Stadden said:

P’s eligible needs have not changed. The issue is that there’s been no progress. [The social worker] has very openly and properly identified a number of different reasons as to why P isn’t engaging, and why she’s neglecting her self-care and refusing to have anything to do with the staff, and certainly the treatment, and now declining even to have anything to do with the epilepsy treatment. […]. The basic premise for [the social worker] is that [P’s mother] is adversely influencing P from engaging positively with the professionals charged with her care. This was the issue from the outset. We have no confidence that she’d comply with a community team. She doesn’t accept that her daughter doesn’t have capacity despite the court having made a final declaration on that. Home didn’t work. The placement didn’t work. The placement with reduced contact didn’t work. She encourages her daughter to (to use her own word) “protest”. This can only be addressed by removing this adverse influence for the time being to allow some positive relationships to be built, to make some progress with the education that needs to follow to persuade P that she should engage with treatments for her own health and well-being. In terms of an alternative placement, that’s not a viable option at the moment. This is a specialist provider in supporting people with a learning disability and autism.

Judge: No progress has been made. The indications are that P is not happy. Why should we persevere with this placement under those circumstances?

Stadden: Because she would not make any progress at home. She would not be socialised if she were to return home, and she would not receive the treatments. Bar the dancing class and the odd trip to [a shopping centre] with her mother and friends who are either significantly younger, or [name] who is her mother’s age, she has no peer group. The issue is how to make her daughter happy where she is.

For P’s mother, Natalia Levine said:

It’s a very draconian step to stop contact completely between family members. It directly impacts on their Article 8 rights and the court has to be sure it’s the right course of action. The court can’t know that in this case. It’s quite clear that P’s presentation has deteriorated over the last few months, and so has her contact with her family. She’s clearly very unhappy. […] She’s a young lady who wishes to have significant contact with her family members. For her to be told that she is to have no contact with them for six months, with no plan backing that up, is surprising and concerning. […] [P’s mother’s] view is that P’s position in that home has become untenable, and trust has broken down, and that’s why an alternative placement should be looked for. She could move more locally, meet her friends, have a less restrictive placement. [P’s mother] acknowledges it’s unlikely that P will be allowed to return home, though that is her ultimate aim. In the meantime, she would like to keep contact with her daughter, maybe even increase it, to encourage P to engage in the process. If you are minded to grant the order the local authority seeks, I would urge you to reconvene this hearing in 2 months’ time, to monitor the deterioration and reconsider.

For the Trust, Joseph O’Brien said:

When, in June of last year, you gave a judgment, you made a significant order that it was in P’s best interests to have treatment for her primary ovarian failure and for her epilepsy […] You said that if P was in the care of her mother then, as we know occurred before, the administration of medication will not be supported, or indeed occur. […] The advantages of treatment are significant and fundamental. It is 100% effective, without risk. It ensures a normal life expectancy and no death by serious fracture or cardio-vascular disease. The disadvantage is that it is against P’s wishes – however she has not been able to form an independent judgment. Those findings in your judgment are as valid today as they were 12 months ago. What we have seen over the last 12 months is little engagement with the endocrine treatment, and continued concerns about the way in which [P’s mother] seeks to influence her daughter as to whether this treatment should take place. Be in no doubt, Your Honour, that the phrases that were used in the diary were, we submit, designed to continue the line of resistance developed by [P’s mother] and imparted to P to encourage her not to engage. It is of considerable worry and concern to the Trust to hear the evidence of [P’s mother] today, which completely rewrites the history books. If she’s right that she’s always supported this endocrine treatment, you may well wonder this: ‘what on earth was I hearing evidence about for days last year?’ And it really was quite staggering to hear her say ‘I have supported this all along’. It elevates her lack of credibility to new levels, Your Honour. And that is really important, because Ms Levine makes a case that you should have trust in [P’s mother] to promote her daughter’s interests. And you can’t have trust in that. If she’d come along and said, ‘I was wrong’, we’d all have to stand back and say, ‘Let’s have a look at this again’. She doesn’t. She says when she was articulating a case for a second opinion, she wasn’t: she’s saying she knew it all along. That, Your Honour, strikes at the heart of the question of trust. How can you honestly trust her to promote P’s welfare when she’s totally unwilling to recognise what her case was last year. That is sinister. That shows a level of formulating a case in order to derail the very treatment that is so necessary to her daughter. We respectfully submit that that evidence reinforces the local authority’s case as to why you should stop the contact. […]. All of it, Your Honour, points towards a failure on [P’s mother’s] part to genuinely and honestly accept that this treatment is necessary. It is part of a game plan to get her daughter back home. And if she goes back home, there is no prospect of this treatment ever taking place. That’s because she doesn’t accept that her daughter lacks capacity to make her own decision. So, when Ms Levine talks about Article 8 rights, I endorse that, and so does the Trust. But the Article 8 right we talk about is a right the hallmark of which is the right to develop as a young lady should, and not be faced with cardio-vascular disease at thirty or forty, or unnecessary fractures to her body. The right to flourish. [P’s mother] seeks to undermine, totally, the need for this medical treatment, and that is compelling in terms of the outcome of this case. It’s not draconian. It’s absolutely vital to ensure that this young lady develops in a way that promotes her health.

For the Official Solicitor, Sam Karim said:

P’s mother has not been positively supporting P to take medication. The explanations from her are not plausible. So, is stopping contact necessary, proportionate and justified? P isn’t having fluids, isn’t dressing, isn’t showering, is plainly unhappy. But it’s more than about social needs. It’s about the primary ovarian failure. It’s a fundamental right. This engages her Article 8 right to develop into a woman, to go from the pre-puberty stage into adulthood. And this continuing delay exacerbates the risk of coronary heart disease and osteoporosis, and it will reduce the efficacy of treatment when it commences. The longer this situation continues, the less chance there is to mitigate the risks and ensure the proper efficacy of the treatment. The question for you is whether complete cessation of contact is necessary, proportionate and justified. If you approve the order sought by the local authority, we suggest a three-month review process. In terms of the Official Solicitor’s position in respect of ovarian treatment, that is a treatment that should commence as soon as practicable and without further delay.

The judge said she would hand down judgment on another occasion. I was not present at that occasion and I am not aware of a published judgment on the case.

I didn’t expect to learn any more about what had been decided for P and her family. I assumed, given the (apparently) universal agreement in court that P should have endocrine treatment for her primary ovarian failure, that this would have been arranged, one way or another, within weeks of the hearing in May 2020.

I was shocked to learn from Claire Martin, who observed the hearing nearly two years later, that this has apparently not happened, despite the view of her endocrinology clinician that there are serious risks to P in failing to receive the treatment, “which risks become ever greater to mitigate as time progresses”.

Hearing on 25th & 28th April 2022, by Claire Martin

This hearing caught my attention when looking in CourtServe because it was listed for four days as a contested hearing – which sounded interesting. When Celia saw the case number, she realised that it was a case she’d seen before and sent me a summary of what had happened at the previous hearing she’d observed.

The applicant this time was P’s mother (who I am calling M, with new counsel – she’s represented this time by Michael O’Brien). She’s applied for P to return to her family home, either in the sole care of her mother (Option A), or in her family home (without her mother living there) with a 24-hour package of care (Option B).

I think that P is still unhappy living in the care home and that she has still not been receiving the medical treatment deemed in her best interests at the previous hearings, and she remains at high risk of medical complications as a result. The reason I say ‘I think’ is because I deduced this from the hearing, rather than it being stated explicitly. There wasn’t an opening summary of the case and its history, and I have not seen the Position Statement for any party (despite requesting these).

The exchange below is what leads me to believe that a) P is still not settled in the care home and b) she is not taking her medications (‘nothing is happening at the moment’). From this I deduce that, because of this situation (if I am correct), M has brought this application, and it is being considered. Otherwise, if P was settled or at the very least taking her medications, why would the court even consider the application (given the previous ruling that it was M who was stopping her taking her medications)?

Judge: [P] herself doesn’t want option B. She wants to live with her mum.

M O’Brien: She wants to live with her mum, who’s put it forward as an option for the Local Authority. It has been raised at the advocates’ meeting. The Local Authority still hasn’t made a decision about whether it’s wiling to fund it. Option A would cost less – a package of care would have carers coming in but would not be 24/7 care.

Judge: Is that the case you want to put forward?

M O’Brien: M is anxious to get on with this but also wants … if it’s the case that Option A is considered by Local Authority, then the best option to get her to take her medications is at home with Mum.

Judge: The Local Authority is suggesting a period of 6 months of supervised contact. [M] hasn’t taken up telephone contact for some time … I would like to know if M would cooperate with the Local Authority, and whether in fact she IS behind the provision of medication for [P].

M O’Brien: Mum says she’s passionate about getting [P] to take her medication now. The best thing would be if she can convince her within a 12-week period to take it – she thinks she can. Mum very much fears that nothing is happening at the moment and that’s detrimental for her daughter. As far as phone contact is concerned, she appreciates the Local Authority wants an evidence base. She’s concerned. She hasn’t spoken to her daughter for TWO YEARS (last time was May 2020). That’s a very long time with nothing happening. She is now very upset and very passionate the medication needs to be sorted, and is convinced that if she’s in a secure environment with mum that’s the only way to do it.

So, M is now saying that returning home to her care is the only way to ensure that P will receive the treatment. The previous ruling (in 2020) was predicated on accepting the argument that the only way to ensure P received her medication was to remove her from her home and significantly restrict contact with her mother.

The basis on which the application is being brought to court again seems to be that P is still not being adequately cared for (she is not receiving the recommended endocrine treatment) and P’s mother is proposing that she is the only person who will be able to persuade P to take it.

Right at the start of the hearing, Counsel for P’s mother said that he wanted to raise the issue of ‘whether this hearing can be effective’. He said that the Local Authority had not visited M’s house to assess viable options for the application for P to move back home, and that this evidence (along with any proposed funding package) was necessary for the hearing to proceed. He was critical of the Local Authority for being unprepared: “It’s unsatisfactory, unhelpful but there we are”.

There had been several delays that morning before the hearing started. It was scheduled to start at 10.30am but the hearing did not get underway until 12.04pm. Statements by counsel suggested that they had been working away in the background to try to resolve the issue of the Local Authority visiting and assessing the home environment, prior to starting the hearing. Given that the application was expressly for P to return home, I was surprised that this assessment had not already been completed.

The hearing on 25th April lasted two hours and was then adjourned until Thursday 29th April, which was a planned short directions hearing to agree the interim court order and establish dates for a final hearing. This hearing had been a planned four-day final hearing, and for all concerned, this situation did indeed seem ‘unsatisfactory’.

At the same time, given that the court order from a previous hearing in 2018 stipulated (medication issues aside) that it was not in P’s best interests to live with her mother, I was confused about the basis on which this application was made, and what had changed.

Joseph O’Brien QC (counsel for the NHS Trust) addressed this matter when invited to offer submissions for the hospital Trust: “Option A [P living at home with her mother] is out of the picture on Best Interests grounds. [There is a] recasting of the findings you made at the original hearing with no evidence as to that change”. I think by this, he meant that M was ‘recasting’ herself as willing and able to facilitate medical treatment for P, despite the court finding, at a previous hearing, that she had actively discouraged her daughter from accepting the recommended treatment.

Given that the original findings had stated that the court had no confidence that P’s mother would facilitate and support any care or treatment plan, I wasn’t sure what had changed to suggest she took a different position now.

On behalf of the Trust, Joseph O’Brien QC suggested that no evidence had been submitted to demonstrate that her mother had changed her view in relation to helping P accept and receive the required medical treatment.

The findings at the previous hearings had been quite damning of P’s mother: that she had “exhibited no motivation to support P to develop a sense of identity separate from her and showed no inclination to assist P to achieve any growing independence”, and “P’s mother preferred for P not to ‘grow up’ and to remain instead dependent on her and isolated, without any outside influence or interference”.

Notwithstanding all of the above, all parties agreed that, given that the application was for P to return to the family home, Local Authority evidence was needed about what the potential options were in the form of a witness statement detailing their recommendations.

I formed a strong sense that this application would not have been countenanced had P’s current care arrangements and relationships been successful at ensuring she received the necessary medical treatment (the main reason she was taken into Local Authority care in the first place).

I am quite baffled as to why it was two years later and P is still not receiving the treatment she needs for her primary ovarian failure.

Jodie James-Stadden (Counsel for the Local Authority) stated:

“The Local Authority has been asked if they would commission a package of care – but for the Local Authority, as things stand, this is hypothetical. The transfer, finding a home …. into P’s name, is not in the Local Authority’s gift. It will require [P’s mother] to have a dialogue with [housing company] which has not been achieved. There is confusion about with whom the responsibility lies. If [housing company] say they wouldn’t consider it, then it’s not on the table. ….. Not the happiest outcome this week.”

Sam Karim QC (counsel for P via the Official Solicitor) focused on the lack of contact between P and her mother:

“I have urged my learned friend for [M] to partake in telephone contact which has been offered since last year – it is proposed as a stepping stone. The Official Solicitor has found it hard to reconcile why she hasn’t.”

Judge: Yes, it has been on offer for 6 months plus.

Karim: I would urge her to reconsider it. She has had no contact.

M O’Brien: I would respectfully suggest that Your Honour reads the Position Statement.

As I wasn’t sent the Position Statement, I’m not sure what Counsel for M meant at this point, but he went on to say that any contact between P and her mother is likely to be emotional and that P herself is likely to ask whether she can go back home to live, at which point the call would be ended by the person supervising contact, since that is a topic that (by court order) is not allowed to be discussed.

Reluctantly, Judge Moir agreed to adjourn the final hearing.

A brief resumption was agreed for Thursday 28th April 2022 at 12 noon to set out the plan for the final hearing, which is likely to be before a Tier 3 judge, probably Mr Justice Poole, in June or July 2022.

The Local Authority will now visit P’s mother’s house on 26th April 2022 and there is a proposed meeting between her and P’s case worker. P’s case worker will be providing a witness statement and recommendations to the court for P’s care, based on her assessment.

Reconvening on 28th April, Judge Moir said: “I have received a document from [the case worker]. It’s the only document I have had, since Monday. I have made extensive enquiries as to when the matter could be listed before Mr Justice Poole. It is not easy.”

It was clear that finding mutually convenient times for all concerned, that fitted with the availability of a (specified) Tier 3 judge, was extremely difficult. The whole system seems tightly stretched.

Jodie James-Stadden confirmed that the order before the court was the same as the one brought on Monday 25th April, and that this hearing was merely to address re-listing of the case. She helpfully (certainly for me!) summarised the current position in relation to the case:

“Information needs to be sought from M’s landlord. The Local Authority needs to look at potential commissioning and whether option B [P living in the family home without her mother living there] is viable. The order also records the Local Authority’s continued offer to M for telephone contact with P, and that M continues to decline that offer. It effectively maintains the status quo [in relation to] residence and care. There is provision for additional 1:1 24hr support for P. … There is provision for M to set out her discussions with the landlord, and the usual permission for the Trust and Local Authority to provide evidence. Then relisting. All parties have agreed it, subject to your approval.”

Judge: Mr M O’Brien?

M O’Brien: Your Honour, the position for [M] hasn’t changed – she wants a hearing as soon as possible. The main purpose of now was to get that date, but the court is not able to get it. I have nothing to add really. On behalf of M, she wants a hearing as soon as possible – if Mr Justice Poole can’t do it, perhaps we can look at other Tier 3 judges for a more reasonable date.

There was a lot of discussion about whether an alternative judge would be possible, or whether the FDLJ (Family Division Liaison Judge) was preferable, what dates were in the offing and whether a sooner date could be offered by a different judge. None of this was resolved at this hearing.

The judge concluded the short (15 minute) hearing thus:

“Right. There’s nothing further we can do this morning, I will approve the order that’s been sent through.”

Reflections

I was astounded that a planned 4-day final hearing had to be adjourned almost immediately. My observations of the court system (connected only to the Court of Protection admittedly) have been that the pressures on the system are immense. Court time is precious. Four days set aside in everyone’s diaries should not collapse at the very start of a hearing.

I wasn’t sure whether the condemnation of the Local Authority (by counsel for M) for coming unprepared to the hearing was fair or not. Given that it was decided that the Local Authority should assess the home environment, his criticism seems well-founded. At the same time, I have some sympathy with the Local Authority position that any assessment is ‘hypothetical’, since the current court order is that P should reside at the placement and should not live with her mother.

I am now interested in such situations: if a court order has been made, can parties who are unhappy with the outcome persist in bringing the case back to court? Or was the application allowed because (it appears) that placing P in the care of the Local Authority has not resulted in the (medical) outcome that was the principal aim of the court order? I am also aware that there are likely to have been additional hearings between the one observed (by Celia Kitzinger) nearly two years ago and the hearing I observed in April 2022, and those hearings may well have resulted in additional directions and orders that have influenced what happened today. (That’s one reason why the parties’ Position Statements would have been so helpful in understanding this case.)

I am reminded of one of the first hearings that I attended as an observer (blogged here). That was about a man with dementia and the application was to medicate him covertly in his best interests, which the judge approved fairly swiftly. I am not advocating one way or the other here, but notice that it was ruled that it was in the best interests of a man with dementia to be medicated covertly, and yet P in this case does not seem to have received court ordered medical treatment for two years, and I don’t know whether or not the options of covert medication (or restraint to ensure treatment) have been considered. (They may have been considered in one or more hearings that we missed).

The discussion at the hearing alluded to care staff being unable to ‘persuade’ P to take her medication and P’s mother submitted (via counsel) that she herself (when she initially had contact) had tried to persuade P to take it. I don’t know the logistics of the specific medication that P needs to take. I just found it curious that the reason P was removed from her mother’s care was to facilitate a necessary and urgent medical regime, and this has not happened. For two years.

Leaving the issue of medication for P’s condition aside, it is clear from submissions from all parties that P has not thrived where she currently lives. I came to this conclusion primarily from what was omitted in submissions, rather than what was included. I strongly suspect that, if P were thriving or at least successfully taking her medications, counsel for the Local Authority would have said so. Evidence (in 2020) from the social worker outlined the same situation at that time (when P had been living in the home for one year). Whilst safeguarding concerns were borne out in the court decision in 2019 to move P out of her mother’s care, it would seem that what has transpired since is that (at least where P is living now) Local Authority care has not been successful, either for expediting medicine delivery or, equally importantly, for P’s psychological wellbeing more broadly.

My heart sank a little reading the evidence from the social worker in 2020, referring to ‘trying to address [self-care and neglect] with health education and communication’. Clearly, I do not know the details of what and how approaches were tried with P, but I thought the omission in all discussions (that I am aware of) missed the key point that P has lost her main attachment figure (whatever is thought about the quality of care that P’s mother provides).

I would suggest that (if submissions by counsel for the Trust are correct such that P was utterly emotionally enmeshed with her mother) taking her away from that relationship without careful attention to P’s attachment needs and how to work with that as a focus (at least initially), would be devastating for P. ‘Health education’ and a focus on actions and behaviour would miss the relational trauma that being wrenched out of her family home and key attachment relationship would have brought (as I said, regardless of the safeguarding issues attached to that home environment). The reports of P retreating into herself, neglecting herself and refusing to socialise would support this possibility.

I am left with two over-riding responses. First, this is a very, very protracted situation for P, not only in terms of the delay in her receiving court-mandated and necessary medical treatment, but also (according both to M and the Local Authority) P doesn’t seem to be adjusting to and engaging with carers at her placement. She was reported to not be washing, not socialising, not eating well and not ‘engaging’ at the 2020 hearing. Her mood (perhaps unsurprisingly if she is living somewhere she does not like) was said to be suffering. The implication at the 2022 hearing (though it wasn’t discussed in detail) was that the situation was the same, which was why M had brought the application. In order to want to look after oneself, get washed, get dressed, join in with life, we all need to have hope. I am wondering whether P has lost hope for herself. Psychologically, it seems difficult to justify P remaining where she is after this length of time.

Second, the forced adjournment of the case seems scandalous in terms of public expenditure. If the application for P to move home has been made and accepted (notwithstanding the previous judgment that P should not live at home with her mother) then surely the parties should have prepared evidence to submit in relation to the application? This evidence was not ready. It didn’t seem to me that any public body was being held accountable for that. Conventionally, costs are not apportioned to parties in the Court of Protection. I have been reflecting on whether this seems fair in this case, when parties have not prepared adequately for a hearing, causing loss of court time, and the huge costs associated with that.

We hope to be able to report on the case from the Open Justice COP project when it comes back to court in June or July 2022.

Celia Kitzinger is co-founder (with Gill Loomes-Quinn) of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She tweets @KitzingerCelia

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core group of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published several blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She tweets @DocCMartin

[1] We are not allowed to audio-record court hearings ao direct quotations from the hearings we observed are taken from contemporaneous notes made at the time. They are as accurate as we can make them, but they are unlikely to be entirely verbatim.

Photo by Mourizal Zativa on Unsplash