By Celia Kitzinger and Claire Martin, 5th September 2025

At a fact-finding hearing at the end of last year, Mrs Justice Arbuthnot found Caroline Grady[1], anonymised in the judgment (Norfolk County Council v CA & Ors [2024] EWCOP 64 (T3)) as “DA”, had acted abusively towards her mother.

The judge said: “There is no doubt in my mind that mother and daughter love each other deeply and DA has certainly cared for her mother as much as she is able to” (§63) – but, she said, Caroline has “personality issues” (§66) – including lack of self-control (§66) – which have led her to bully her mother. “It is a dysfunctional, volatile relationship with a mother and daughter who are enmeshed and depend on each other emotionally” (§66).

Although Caroline’s mother (we’re referring to her as “Mrs P” since the judge changed the initials she used for people across judgments) was found to have capacity to make her own decisions about contact, the judge found her to be a “vulnerable adult” in need of protection from the “undue influence” exercised over her by her daughter. This means that contact between mother and daughter can be regulated and supervised under the inherent jurisdiction (see §128-§151 of the judgment, for anyone unclear about how the inherent jurisdiction works). Supervised contact arrangements were initially given by way of an “undertaking”, and later imposed by the court via an order with a penal notice. Caroline breached both the undertaking and the court order concerning contact with her mother.

In February 2025, there was a committal hearing for contempt of court (Norfolk County Council v Caroline Grady [2025] EWCOP 15 (T3)). We’d blogged previous hearings in this case several times before[2], but we weren’t able to report properly on the committal due to reporting restrictions – and the judge said that she did not intend to publish a committal judgment. We wrote about the committal hearing in the only way we could, while complying with reporting restrictions. It was pretty opaque, as you can see here: “Draconian reporting restrictions in a contempt of court case: Severing continuity between judgments”.

We subsequently made a successful application to the court for the reporting restrictions to be varied and for the committal judgment to be published – and there’s a published judgment about the transparency application too (Norfolk County Council v CA & Ors [2025] EWCOP 16 (T3) in April 2025). We plan to publish a separate blog post about the transparency issues relating to the committal proceedings.

So effectively, the situation now is that certain “facts” are on public record about Caroline’s behaviour towards her mother – some of which were breaches of undertakings and orders resulting in fines against her – and the court is now trying to find a way forward to support contact between mother and daughter in ways that don’t expose the mother to further “abuse”.

Caroline does not accept that the findings of the court are all actually “facts” – and in truth the “balance of probabilities” test used in this civil court means up to a 49% chance that these “facts” never happened. Even when Caroline agrees that the thing the judge says happened did in fact happen, there is a world of difference between how Caroline and the judge understand and interpret it.

Despite the proven “facts”, some unsupervised contact (initially 15 minutes in person) was introduced in Spring 2025 and the intention of the court is that this should be gradually increased (if things go well). Caroline is concerned that the increase in unsupervised contact will leave her vulnerable to accusations of further “abuse” and will also mean reductions in her mother’s care provision. This is likely to be a matter before the court at a hearing in October 2025.

In this blog post, we report on the case by connecting the fact-finding hearing and the committal (which we were previously prohibited from doing) and expressing some opinions about the fact-finding hearing. We have delayed this blog post a few months because Caroline Grady had opposed Celia Kitzinger’s application to vary the transparency order (variation was essential for publication) and was opposed to publicity about the fact finding and committal. She described it as being “publicly disgraced” and worried about its implications for her job. Caroline’s father also opposed the application, He said in court: “It’s a private affair. It shouldn’t be mentioned in public. The whole thing has been a big misunderstanding …. We’ve been dragged through the courts for a year and a half – we don’t want our names published”.

At that same transparency hearing (on 11th April 2025), Caroline Grady raised her “right to reply” and to “defend herself” against the “vile judgment” that would now be published. The judge (wisely I think) pointed out that “sometimes it’s better to step back and things go away more quickly” – in effect, suggesting that by contributing her own version of events, Caroline might simply add more fuel to the fire of publicity. But I was asked by the court to address Caroline’s “right to reply” and I said that “I take the point that this might fuel publicity and you need to think carefully about whether you want to do that or not, and discuss it with your family” – but I also said that if my application (which she opposed) was successful, then yes, she would be able to write a response and give her account of her experience in the Court of Protection, as had other litigants in person before her, including Amanda Hill who was in court observing that day.

We left it with Caroline and after some e-mail exchanges and a first video-chat (and my reminder of the judge’s suggestion that it might be better not to add to the publicity by contributing her voice), Caroline expressed the strong view that she did want to contribute to the blog post from her own perspective.

So, there are three sections here.

First some more detail about the background and history of the case – the contact restrictions and the committal (by Celia Kitzinger).

Second, reflections from an observer who watched three of the court hearings, including the committal (by Claire Martin).

Third, a conversation between Caroline Grady and Celia Kitzinger, which was sent to Caroline for checking and which she has given us permission to publish.

1. Background – Celia Kitzinger

I’ll address first the contact restrictions as they were applied under the inherent jurisdiction, and then summarise the issues at the contempt of court hearing.

1.1 Contact restrictions and the inherent jurisdiction

In Spring 2023, Mrs P, in her late 70s, was in hospital with a chest infection. While she was there, hospital staff and a hospital social worker became concerned about the mother/daughter relationship. It’s since been described in judgments as “volatile”, “fiery”, “tempestuous”, “tumultuous”, with “loud arguments” between the two of them.

According to the hospital, Mrs P’s daughter, Caroline Grady, had made her mother walk around the ward when she was reluctant to, told her she was not drinking enough, was verbally aggressive, and called her “a senile old woman”. Caroline later accepted that she’d behaved in this way, explaining that she was trying to keep her mother alive. What the hospital saw as abuse was (she said) typical banter between mother and daughter that had been part of their relationship for decades. The hospital made a safeguarding referral to the local authority, Norfolk County Council.

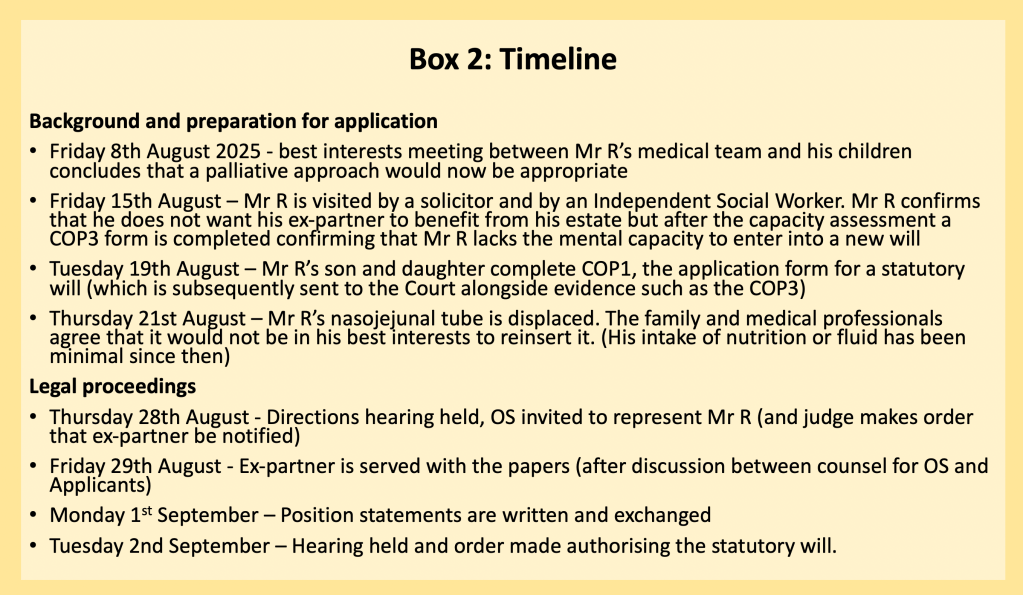

On 18th December 2023, Norfolk County Council made an application to the Court of Protection after an alleged “lasagne-throwing” incident – which had seen the daughter arrested and released on bail on condition that she had no contact with her mother for the next three months. And that was the beginning of a long and painful saga in the Court of Protection that we’ve been following for some time.

The first hearing of this case (COP 14187074) was before HHJ Beckley on 17th January 2024 (and we blogged about it here: “When two legal teams turn up in court to represent P”). By the time of that first court hearing, the bail conditions had expired, but the judge (HHJ Beckley) asked Caroline and two male family members, to give a formal undertaking that they would only have contact with Caroline’s mother (who lived in her own home not far from her daughter) with a carer present. They made the undertaking with reluctance and some indignation.

There was disagreement in court about whether the next stage should be a “fact finding” hearing (i.e. to determine whether or not Caroline and the two male family members coercively controlled and abused Mrs P), or whether it should focus on “capacity determination” (does Mrs P have capacity to choose for herself where she lives and receives care, who she has contact with – and indeed to litigate this case through her own legal team rather than having the Official Solicitor act on her behalf, as she claimed at the first hearing). The judge decided that capacity determination should take priority.

There was contradictory evidence about Mrs P’s capacity before the court at this point, and resolving it was important, because if Mrs P had capacity to decide for herself whether or not to have contact with her daughter, then the Court of Protection had no right to make those decisions on Mrs P’s behalf.

In the meantime, the local authority made clear that even if Mrs P were to be found to have capacity to decide for herself about contact with her family, they would continue to try to protect her from her family members. On 25th April 2024 they made a parallel application under the inherent jurisdiction[3] instead of under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. That requires a High Court judge (more senior to HHJ Beckley). The case was therefore transferred from HHJ Beckley (who would not be able to impose contact restrictions on a capacitous Mrs P) to Mrs Justice Arbuthnot (who would be able to impose contact restrictions under the inherent jurisdiction).

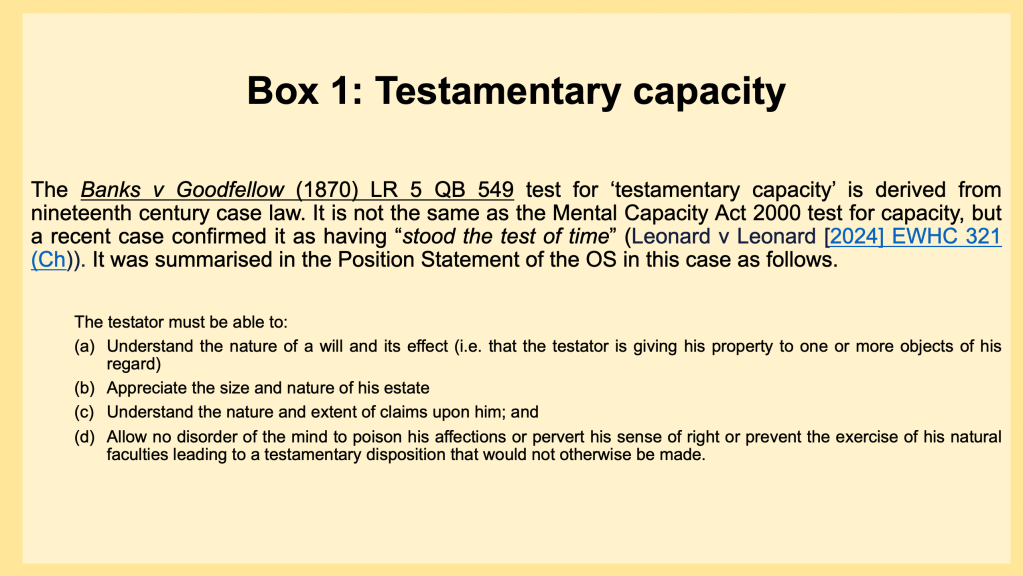

As it turned out, Mrs Justice Arbuthnot found that Mrs P does have mental capacity to make her own decision on contact with her family members. After careful consideration of competing (and in the case of the expert witness, revised) assessments of Mrs P’s capacity across different areas, the judge found that Mrs P lacks capacity to conduct the court proceedings, to make decisions about her care and to manage her property and affairs – but that she has capacity to make decisions about contact with her daughter, and also has capacity to enter into or revoke an LPA.

In relation to mother/daughter contact, the judge said: “[Mrs P] was making unwise but capacitous decisions about contact with [her daughter]. It is a relationship that is of great importance emotionally to [Mrs P] and although [her daughter] is as [Mrs P] says ‘brutish’ and ‘bullish’ she is doing her best to keep her mother alive and as healthy as she can persuade her to be. [Mrs P] recognised the relationship had negatives but considered the positives outweighed these. I found in this finely balanced case that she had capacity to decide on unsupervised contact.” (§124 Norfolk County Council v CA & Ors [2024] EWCOP 64 (T3)).

Over the course of the same multi-day hearing (between 2nd and 7th October 2024), the judge also made some fact-finding decisions (and she made them first[4]). She found that allegations against Caroline (plus two against Mrs P’s ex-husband) were proved on the balance of probabilities: they included Caroline shouting at her mother, calling her a drug addict, force-feeding her pizza, forcing her to exercise and walk around when she was in pain, threatening that she’ll be moved to a care home, making references to Dignitas (the Swiss assisted dying clinic) – and pouring lasagne over the mother’s head and then smearing it into her face and hair. Caroline partially accepts some of these allegations (though her view of them is very different – she’s trying to keep her mother up, moving around, and alive). She totally rejects other allegations, including both the pizza and the lasagne incidents as being entirely untrue – “set up” by the carers as part of a “vendetta” against her.

Here’s how the judge summarised her view of the situation [DA is Caroline Grady, CA is Caroline’s mother]:

§63 Overall as I look at the evidence as a whole, I find that DA fails to make any allowances for her mother’s age and frailty. She is hoping that by force of her personality she can keep her mother healthy and able to look after herself. There is no doubt in my mind that mother and daughter love each other deeply and DA has certainly cared for her mother as much as she is able to.

§64 I am concerned too that DA has persuaded her mother that she is lazy and stubborn and that her failure to look after herself better is her own fault. I consider that that view has arisen from what CA has been told repeatedly by DA in the same way that CA’s fear that she will be moved into a care home comes from her daughter and indeed EA on 20th November 2023, when the court and the local authority have been at pains to make it clear that that was not – and is not – the intention.

§65 To that end, DA bullies and forces her mother to do the things that she believes will keep her alive for longer. When she force-feeds her it is because her mother is not eating enough and she has had anorexia. Their relationship of verbal abuse is mutual, but CA is ageing and getting increasingly frail and deserves a different approach from an adult daughter.

§66 I am no expert, but after seeing DA in court in the four-day hearing and on other occasions before this, it is the daughter’s personality issues that lead her to treat her mother in the way she does. She lacks self-control and in particular she is unable to control her anger at times. CA describes her daughter as bullish and brutish, and I agree with that description. It is a dysfunctional, volatile relationship with a mother and daughter who are enmeshed and depend on each other emotionally.

§67 I have carefully considered DA’s argument that the local authority are “out to get her” (my words, not hers). This is simply not the case. The safeguarding concerns originated from the hospital where any number of different staff reported DA’s concerning behaviour towards her mother. These complaints then continued via the care agency. The social work team have primarily gathered the information together to get a picture of the relationship and the way this elderly lady is treated by her daughter. Norfolk County Council v CA & Ors [2024] EWCOP 64 (T3) 10th October 2024

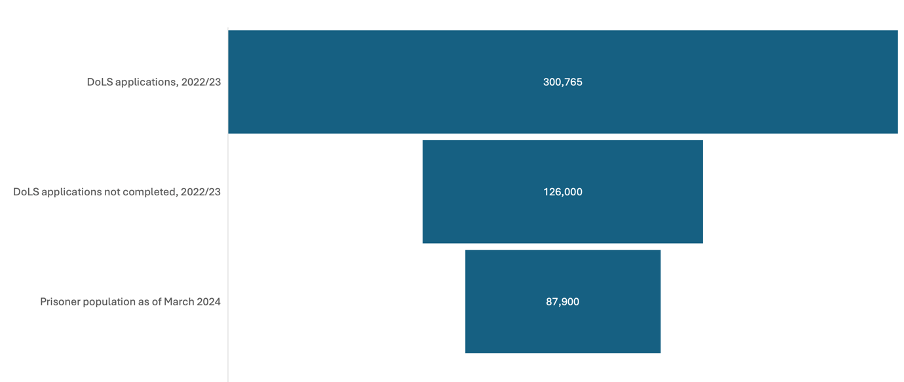

The judge used the inherent jurisdiction ‘to impose a supervised framework around contact’ (§142, (Norfolk County Council v CA & Ors [2024] EWCOP 64 (T3))). This meant that all contact between Mrs P, her daughter, and her ex-husband would be supervised by one of the (live-in) carers. The judge was fortified in this decision because a graph, presented by Mrs P’s social workers, showed a decline in the number of “incidents” since the daughter had made undertakings about contact.

Contact restrictions and the intrusion into family privacy caused by the court order that a carer must always be present have clearly been painful to Caroline, especially at Christmas. We blogged about her application for 12 hours of unsupervised time on Christmas Day 2024 here: “Let us be alone as a family again”: An application for unsupervised contact at Christmas” There are still contact restrictions in place but the plan is to increase the amount of unsupervised face-to-face contact in the run up to the October 2025 hearing from 15 minutes a day to 30 minutes and then to an hour (assuming that there are no problems), plus a plan for ceasing supervision of phone calls too. At the last hearing, however, Caroline Grady indicated that she had some concerns about this, fearing further accusations against her.

There’s also an injunction hanging over Caroline Grady. The judge allowed the LPA for health and welfare to remain in force, but circumscribed the attorney’s powers by way of an injunction under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (as Mrs P lacks capacity to decide on her care). These injunctions state that Caroline:

- … shall not install any camera, listening equipment or loudspeaker in [Mrs P’s]’s property, whether live-feed only, or live-feed plus recording.

b. … not tell or suggest to [Mrs P’s] carers how to meet [Mrs P’s] care needs, or purport to hire or dismiss carers

c. … shall not lie to, threaten, harass or intimidate [Mrs P]

d. … shall not force [Mrs P] to exercise.

e. .. shall not force-feed [Mrs P]

f. … shall not mention or threaten to send [Mrs P] to a care home, or to Switzerland.

g. … shall not deny [Mrs P] access to healthcare assessments or interventions.

h. … shall not take steps to prevent [Mrs P] from being administered prescribed medication.

i. … shall not seek to discharge [Mrs P] from hospital against medical advice.

j. … shall not take steps to prevent social services and other social care, or healthcare practitioners from visiting or speaking with [Mrs P] alone.

k. … shall not take steps to move [Mrs P] to another place of residence.

1.2 Contempt of court, a committal hearing and a fine

At an earlier hearing in July 2024, another issue had arisen. The local authority claimed that Caroline (and her father, Mrs P’s ex-husband) had breached the undertakings they had made to HHJ Beckley at the beginning of the year (we blogged about that here: Complex issues for the court and plans for an ‘omnibus’ capacity hearing). The undertakings they were alleged to have breached included contact restrictions (they had been with Mrs P without a carer to supervise them) and also they had mentioned the possibility of Mrs P being moved to a care home. The judge was emphatic that: “NOBODY must mention care homes to her. […] it’s not on the table, it’s not proposed, this lady wants to stay at home. It is NOT to be talked about”. The court proposed a hearing in January 2025 to consider (as the published judgment states) “an application for committal for contempt for alleged breaches of undertakings given to the Court…”.

Amanda Hill and Claire Martin attended the committal hearing in person. They wanted to blog about it, but were effectively prevented from doing so, in any meaningful way, due to draconian reporting restrictions imposed by Mrs Justice Arbuthnot. The judge created a new transparency order that effectively banned reporting on the substantive content of the committal proceedings including, in particular, reporting on the proceedings in any way that connected the committal with the previously published fact-finding judgment, and with blog posts and other published legal commentary about the case. They wrote about the problem here: “Draconian reporting restrictions (now lifted) in a contempt of court case: Severing continuity between judgments”. Pretty much all the observers were able to say about the substantive content of the hearing was this: “we observed a committal hearing at the Royal Courts of Justice at which someone was found to be in contempt of court for having breached undertakings and injunctions and given a (non-custodial) sentence”. At that stage, there was no published judgment and no intention to publish one.

Celia Kitzinger subsequently made an application to the court to vary the transparency order from the committal hearing and for the judgment to be published. This was successful: the committal judgment is published, naming Caroline Grady (Norfolk County Council v Caroline Grady [2025] EWCOP 15 (T3)) and there is also a published judgment concerning Celia’s application (Norfolk County Council v CA & Ors [2025] EWCOP 16 (T3)), which might be useful to other people making applications to the court to ensure that committal proceedings are properly transparenct.

According to the committal judgment, Caroline Grady had made an undertaking that she agreed to her contact with her mother being supervised until further order and that she would not use insulting or threatening words or behaviour, or say or do anything that would cause her mother upset or distress, or which may undermine the care provided to her. However, she’d breached these orders by questioning her mother about a proposed hospital visit (causing her mother to become angry) and on a different occasion she’d distressed her mother by saying “your bloody dementia has prevented you from remembering everything we have talked about in the last months, it’s a bloody waste of my time”; another time she told her mother she’d be going into a care home.

The committal judgment also reports that Caroline had breached an injunction forbidding her from telling lies to her mother, and that she “shall not mention or threaten to send [her mother] to a care home or to Switzerland”. The judge found that on 13th November 2024, contrary to those two terms of the injunction order made, the defendant lied to her mother when she said that the local authority might take her to a care home, and in saying this she knew of course that she was saying something that would be upsetting to CA.

The sentence was a fine of £500. It’s the first time any of us has seen a fine as a penalty for contempt in the Court of Protection.

2. Reflections from an Observer – Claire Martin

I have observed three hearings in this case: on 6th June and 2nd-3rd October 2024 (remotely) and then the committal hearing on the 28th January 2025 (in person). I will reflect here on two aspects of the case which have caused me some disquiet: first, how the mother-daughter relationship in this case has been framed in court (and more generally, how relationships are policed by the state); and second, how allegations become ‘facts’ (on the balance of probability) in the Court of Protection, and the implications of that for family members.

2. 1 Relationships

Relationships, by their very nature, are not one-sided. The judge in this case (in the fact-finding judgment at §65) recognised that in this mother/daughter interaction “[t]heir relationship of verbal abuse is mutual…” and continued “… but CA is ageing and getting increasingly frail and deserves a different approach from an adult daughter” (CA in the judgment is Mrs P, the mother at the centre of this case).

How much should the fact that one person in a relationship is getting older and frailer mean that the other person should (or could) change their lifelong patterns of relating within that relationship? And if the ‘verbal abuse is mutual’, how much responsibility can be handed to one person in that relationship? In this case it seems that Mrs P does not in fact have dementia (at least, nobody seems to be insisting on that as a correct diagnosis since the psychiatrist witness questioned it in his evidence to court), and, although she is frail physically, and has some cognitive deficits, this does not necessarily mean that her ways of relating to others will change – often quite the opposite. I am a psychologist working in older people’s mental health. I have witnessed, over the years, many frail, older people being forthright, provocative and what might be described as ‘verbally abusive’ within their close relationships. (Imperfect) patterns of relating are very persistent across the lifespan – especially if people don’t necessarily see any need to change them.

Caroline’s own account of the mother-daughter relationship, reported earlier by Celia, is that ‘[w]hat the hospital saw as abuse was (she said) typical banter between mother and daughter that had been part of their relationship for decades’. Caroline, in one of the hearings I observed, told the court that her mother tells her ‘to go and play in the road’ and other such injunctions, when they are arguing. This is the way, she says, they interact, and always have done.

It’s very hard to really know what the reality of people’s relationships is. Viewing ‘incidents’ in an additive way from a particular lens of what one might think of as ‘normal’ or acceptable behaviour could, arguably, end up painting a very different picture to that of the reality of people’s messy relationships. In this case, it must be remembered that Caroline is now being allowed increasingly longer periods of unsupervised contact with her mother. It seems then that the court does not see her as an ongoing risk to her mother’s wellbeing.

How much can we as a society expect the state to police our relationships? In Mrs Justice Arbuthnot’s judgment she said:

§17 The undertakings given by the defendant were that she agreed first to her contact with [her mother] to be supervised until further order and second that she would not use insulting or threating words or behaviour, or say or do anything that would cause [Mrs P] upset or distress, or which may undermine the care provided to [Mrs P] until further order. The undertakings were renewed on 24th April 2024.”

Whilst we might know that saying or doing a specific thing has the potential to cause someone distress, whether or not they in fact are distressed by our words or actions is not within our control. We can also say or do the same thing on different occasions, yet it might lead to a different emotional reaction due to the other person’s state of mind on those two occasions. Furthermore, sometimes we all, at times, want and need to say things to each other that we know might be upsetting to hear. Sustaining a relationship where one person is bound by the court not to ‘say or do ANYTHING’ (my capitals) that would cause distress to the other, is, I would argue, impossible. I am not sure how anyone could ever comply with it, even if they tried.

The committal judgment goes on to state:

§45 The features in this case which aggravate the penalty are the following:

In saying what she had to DB the defendant had caused harm to her by upsetting her. The undertakings and injunction were put in place to prevent the defendant saying or doing things which would upset DB.”

It seems unrealistic to me, and unfair, to require an undertaking that someone does not ‘upset’ another person. Surely court injunctions should clearly stipulate what a person’s actions must or must not be? This undertaking relies on a crystal ball in relation to person B’s response, not person A’s behaviour. When does safeguarding a vulnerable person tip into unreasonably and unrealistically policing other people’s (always ‘imperfect’, sometimes volatile, sometimes ‘enmeshed’) relationships?

2.2 Judicial construction of “fact”: The lasagne incident

It was alleged by social services that on 21st September 2023, Caroline threw lasagne over her mother’s head in a fit of anger.

An important part of the context is that Caroline’s mother had recently been in hospital. Caroline says, and the judge accepts, that the daughter played a significant role in keeping her mother alive during her hospital admission. Caroline says that she tries to motivate and encourage her mother, in ways that she always has done, to keep active and eat to enable her to be as healthy as possible. It’s some of these efforts to influence her mother’s behaviour (to keep her alive) that are seen as abusive and controlling by the court.

I have been curious about the lasagne incident – now found by Mrs Justice Arbuthnot to have happened as a “fact”. Interestingly, although she admits to other incidents reported to the court, the lasagne incident is one that Caroline Grady vociferously denies ever happened.

These are my contemporaneous notes from the fact-finding hearing that I observed (remotely) on 2nd October 2024:

Counsel for Mrs P: If your mum threw lasagne up in the air how did it end up under her chin?

Caroline: It went EVERYWHERE!

My note to self at that time says: “I find this an odd question – that could easily happen surely? How would anyone in court know what a plate of lasagne tipped over someone’s head looks like, as opposed to a plate of lasagne flipped upwards that lands on the head?”.

Caroline’s version of the story is that it was her mum who became angry and flipped the plate upwards, and Caroline was then trying to wipe off the lasagne from her mum’s hair, face and chin.

Caroline’s submissions at the fact-finding hearing (representing herself) were as follows:

“I maintain that these incidents did not happen and I invite the court to find these incidents unproven. I categorically deny Allegation 29 that I tipped a bowl of food over my mother’s head. A bowl of lasagne. [Caroline read out the carer log about the argument and Mrs P’s refusal to go for walk]. After filling out the log, she also says ‘[my mother] plopped her food on the pouffe…’ Significantly there’s no mention of me smearing the food over mum in a rough manner. It seems to me that the [carer’s] statement was prepared for her and is not accurate. I have always maintained I did not do it and she was in the kitchen. She has always maintained that she witnessed me pouring the food over my mother. Yesterday, she admitted she was in the kitchen and did not witness this incident. I submit that this places substantial doubt on her witness evidence and that Norfolk County Council have not satisfied the burden of proof.”

The judge gave an ex tempore (oral) judgment of the alleged lasagne incident, which I typed contemporaneously: “[The] wholly contested incident – lasagne. [Caroline’s mother] closed her mouth and lasagne was spilt, when the carer came out of the kitchen she could see [Caroline] smearing food on her mother. [Caroline] said she was picking food out of her hair. [There is a] contemporaneous note but also a photo. As I said [Caroline] denied doing this, but I find the allegation all too likely. [Caroline] lost her temper and threw food at her mother. The photograph confirmed the allegation. [Judge then said that the fact the carer hadn’t SEEN it does not undermine her evidence] The distance was short [from the kitchen to the lounge] and lighting was good. This is all about a lack of control, exhibited, AGAIN, by [Caroline]. It’s a constant refrain in this case that everyone else is wrong and that [Caroline] is right. I do understand the difficulty – I would describe their relationship as enmeshed. The carer would have no reason to lie. I find all the allegations [the carer] made, proved.” [judge’s emphasis]

So, it transpired at the fact-finding hearing on 2nd October 2024, that the carer had not actually seen the alleged incident. The judge found it “all too likely” that Caroline did throw lasagne on her mother’s head, and she relied in part on the broad canvas of evidence before her about Caroline’s character and behaviour – Caroline’s “lack of control” and her “constant refrain that everyone else is wrong”. Similarly, in relation to allegation 15 (about verbal abuse that Caroline describes as their usual ‘banter’) the judge’s oral judgment was “[i]n my judgment it is JUST the sort of thing that [Caroline] would do” [judge’s emphasis]. Other observers, like me, got the strong impression that the judge didn’t really like Caroline very much.

Meanwhile, according to the judge, “the carer would have no reason to lie”. Really? That’s not my experience of the veracity or otherwise of health and care teams’ records. They’re often taken as fact, because they are written by ‘professionals’ and constitute the service user’s ‘records’ (most often unseen and unverified by the service-user themselves). They are always just one side of the story though, one person’s or team’s perspective. Anyone who has experienced a family member in a hospital or care home will likely know from personal experience how many errors (mostly inadvertent, some representing an ‘outsiders’ perspective, and some of which seem deliberate ‘cover-ups’) creep into the records.

A report by the Professional Standards Authority, called ‘Dishonest behaviour by health and care professionals’ found that: “frontline staff and professionals of varying levels of seniority reported personal experience of dishonesty in a professional context, most commonly falsifying records, false reports of conduct or patient interactions or theft and fraud”. Some NHS staff“saw the regulators as overwhelmed by the incidence of dishonesty cases” and as ineffective and slow to respond even to serious cases (p. 18). Some health and care professionals described the dishonesty as “endemic”: they said there was a culture of covering up failures or incompetence, and that “a lot of the time it’s just glossed over” (p.18).

This view of dishonesty in health and social care – from professionals themselves – is a very different view from the one Mrs Justice Arbuthnot seems to hold. She cannot conceive of reasons why any professionals would lie – as here, in the published committal judgment which states, in relation to the veracity of a carer’s witness evidence [BB is the carer]:

§36. I accept that there was no mention of the conversation or of the defendant being in tears in the carers’ log, but having said that, I saw no reason why BB would have lied about this. She made the notes in the incident report form the following day. She had no prior knowledge of any issues that there had been with the defendant. There may have been a note that careful observations had to be made but it seemed to me she was clearly honest in her account.”

And §37 “She could have no reason to lie or make this up. Why would she?”

Of course, I have no direct knowledge of whether or not the lasagne (or other) incidents occurred as alleged by social services’ carers. I do feel somewhat uncomfortable about the judge’s suggestion that the carer would have ‘no reason to lie’. People lie for all sorts of reasons. Caroline suggests a ‘vendetta’ against her by Social Services (which is currently funding 1:1 live-in care for Mrs P). I wonder whether there might be a possibility that the carer was not lying but (given that she did not actually see the incident) could have misinterpreted what she saw as she returned from the kitchen – seeing Caroline’s mum upset and Caroline touching her head (‘smearing’ it or ‘picking’ it out?) where the lasagne was now located.

As someone who works in the NHS, the judge’s apparent assumption that health and social care professionals would not lie, let alone have no reason to take a particular view and then look for and find evidence to support that view, leaves me feeling very uncomfortable. Systems of care can become closed shops, care teams gossip (did this carer really have ‘no prior knowledge of any issues that there had been with the defendant’? She was, at the very least, told that ‘careful observations had to be made’), service users’ and families’ reputations are often solidified and labels stick. Carers are human, and all of us can have feelings of wanting to show someone up, get them in trouble etc., if we don’t like them or they are (said to be) unkind to a vulnerable person. Agencies often have their own agendas (for example, Caroline maintains that police records show that social services were looking for evidence to remove her mother to a care home – see the interview with Celia below) and might encourage carers to specifically look out for certain types of incidents to enable those agendas. The rhetorical ‘why would she?’ question seems naïve to me and not cognisant of how systems of care often operate.

In her published judgment (Ms X is the carer who had been in the kitchen at the time of the incident) Mrs Justice Arbuthnot says that: “the photograph which showed a spread of lasagne above and below [Mrs P’s]’s chin confirmed Ms X’s explanation of what had occurred and not [Caroline’s]” (§51). The judge made this analysis of the photograph (as she says) ‘without being an expert’ and without expert witness evidence on food spatter analysis.

I am not an expert on food spatter either, so I decided to look up how spatter is analysed and how easy it is to make inferences from what is seen after the fact. It seems to be a complex and specialist skill to be able to interpret images of spatter. We might be most familiar with discussion of blood spatter from crime dramas, and from what I’ve read similar principles apply to analysis of food and liquid spatter. Factors of importance are: velocity of impact, angle of impact, ingredient viscosity and size, height of the fall and surface texture. Interestingly a Google search asking ‘If lasagne was tipped over your head what would the spatter look like?’ says: “Ingredient Viscosity and Size: Thicker ingredients like pasta and meat will travel further as larger, more irregular blobs and splashes, while the thinner sauce will create smaller, more distinct droplets.” Could lasagne flipped upwards ‘travel further’ and end up on top of the head and below the chin as it travels upwards?

And this search, asking about food spatter more generally, states: “Complexity of Patterns: Food spatter patterns can be more complex than blood spatter due to variations in viscosity, surface tension, and other factors. Subjectivity: Interpreting spatter patterns requires experience and expertise, and there can be some degree of subjectivity involved in the analysis. By carefully analyzing the spatter patterns, investigators can gain valuable insights into how food was spilled, including the direction, force, and potential source of the spill.”

I’ve reproduced below the full paragraph from the published judgment, dated 10th October 2024, referring to the incident:

§51 As I said, [Caroline] denied doing this to her mother, but I found the allegation all too likely. [Caroline’s] anger at her mother’s refusal of food got the better of her. She lost her temper and threw it at her mother. Ms X’s description was accurate. Without being an expert, it seemed to me that the photograph which showed a spread of lasagne above and below [Mrs P’s] chin confirmed Ms X’s explanation of what had occurred and not [Caroline’s].

My brief research suggests that understanding how food spatters is a complex matter. I am not sure how the judge could confidently reach the conclusion that the photograph ‘confirmed’ the carer’s (unwitnessed) explanation of what had happened. It seems more likely to me, given the absence of eyewitness or robust spatter evidence, that the finding of fact that Caroline did tip lasagne over her mother’s head is based solely on Mrs Justice Arbuthnot’s view that ‘this is just the sort of thing’ that Caroline would do.

3. Caroline Grady’s conversation with Celia Kitzinger

Caroline and I spoke for just over two hours one evening in late August 2025 about the case and her views about the court and social services, and what had happened to her family.

I thought it reflected very well on Caroline that she was willing to speak to me at all. It was my successful application to the judge for the committal judgment to be published that put Caroline’s name in the public domain, which she most definitely did not want. She opposed my application in court, and finds it humiliating (and potentially threatening for her career) to have a public judgment saying that she “abused” her mother. But now that her name is in the public judgment, she can see the benefits to making her version of what happened public too. Caroline was gracious about the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, saying that she supports the principle of open justice and transparency – despite the personal grief my actions have caused her in this instance.

“The principle of what you do – I think it’s great. I know I didn’t want you in court and I thought it was our private business and I didn’t know what you were doing or why, but now it’s out there anyway, this gives me a chance to tell the truth. I’ve been named and shamed for something I haven’t done. When you read that fact-finding judgment, I sound like an evil bastard, don’t I. I sound like I really abused my mother. But at least this gives me the option to talk about the case.”

Having been publicly named by the court, Caroline is free to speak about her experience in her own name, and to tell her own story. This is important to Caroline – as it is to many people caught up in legal proceedings . Families often want to tell their stories and to expose the “injustice” they have endured. The court, she said, is “like a secret cult going around the same barristers, same solicitors, same judges, just making up the rules as they go along. Your Project is making people aware of what goes on behind closed doors”

Like most families with Court of Protection involvement, the whole experience has been a “torment” for her. “What’s been happening is on my mind every day. There’s so much scar tissue there – it will never leave me. I’ve lived and breathed this, day and night, writing letters, trying to find ways to help Mum, to help the family, to stop the ridicule. It’s like being in the middle of a horror film you can’t get out of.”

In particular, Caroline is adamant that the judge was simply wrong to find as a fact that she poured lasagne over her mother. That never happened, she said: “You know how you feel when you’ve done something wrong. Like if I had of thrown lasagne at my mum, I’d think, “Oh okay, I was guilty and I got found out”. But when you’re actually innocent! I feel like an innocent man hanged. I’ll go to my grave knowing that I never poured lasagne over my mother. But I’ve been caught on the “balance of probabilities”. And the police evidence shows I didn’t. And it shows that Social Services rigged the notes. It’s all there in black and bloody white! And the judge has patently ignored it.”

Caroline reminded me that although social services said that a carer had witnessed the lasagne being thrown, in fact that carer had “told the police that she hadn’t seen me throw the lasagne, but social services had written down that she had. [… ] When we were in court and [the carer ] said “no, I was in the kitchen”. I’m going “YES! Now your lies are all exposed!” But oh no, according to the judge, the fact that she was in the kitchen doesn’t change the fact that the notes they rigged say she saw you throw the food. How can I ever clear my name?”.

Caroline believes that social services had “deliberately lied” about the lasagne incident (and other matters), motivated by their wish to portray Caroline as a monster, so as to enable them to remove Mrs P from her home (where she has an expensive care package) and put her into a care setting (which would be cheaper for them).

It’s very clear to me that Caroline is desperate to protect her mother from going into a care home – it’s one of her greatest fears that social services will do this. Although Arbuthnot J stated clearly in court that there was no intention to put Mrs P in a care home, Caroline says that the police records that she obtained following her arrest demonstrate otherwise.

“I want you to report this. 15th September 2023 at 11.21 (this is one week before the lasagne incident). The social services person told the police officer with MASH [Multi Agency Safeguarding Hub] (Caroline is reading the next sentence from the report)“adult social services are currently looking at ways that [Mrs P] can be removed from the home and put into a care setting. However, this is not an easy process”. Their intention, written down in black and white by a police officer, was to have my mother taken out of her home and placed in a care setting. That’s what they said – and the judge just completely ignored this – but it’s all written down that Social Services were trying to find a way to take my mother out of her own home and into a care setting, but the family were proving ‘a difficult obstacle to overcome’. And then – how convenient! – a week later I was arrested!”

She describes how traumatic the arrest was: “When they came round here and said, “you must come down to the station with me – you’ve been accused of ABH and I knew I hadn’t done anything. “It’s a mistake!”, I told the police, “I’ll come down later and chat”. I said – I’ll never forget and I can’t get my head around that – I said, “well, no, I’m not even dressed!”. They said, “We’ll watch you get dressed”. I said, “No you won’t! Go away – I’ll come round later!”. Because when they came to my door, I thought someone had died, you know. When the police come to your door, initially you think someone’s passed away, a loved one, and then, when I was sitting there with this dressing gown on and they were saying, “now there’s ABH”, my reaction was – well, I said, “what are you going to do if I don’t come?” and they said “we’ll arrest you” and I said “well, bring it on then!”. And it was such a claustrophobic feeling, once those cuffs were on, I went round like a headless chicken in here. I was shouting for the neighbour to go and get my father and then, when they were holding me down, in the chair just there, my head- I had bruises black and blue, I thought they’d done a rotator cuff injury, I nearly suffocated in the chair – and it was like slow motion. [My partner] was at work. He came in and saw the place had been pulled around, but do you know they were three months with all my personal data on my phone, going through- I don’t know what they were looking for. What did they think they were going to find? They put me in a cell. They wouldn’t give me any water. I was allowed one phone call. And [my partner] said, “well where are you?”, I said, “I’m in a prison cell” and everyone starts laughing, they don’t believe me. I’m so claustrophobic, and I still have nightmares, and I’m still waiting for counselling about being in that prison cell. I was in that cell nearly six hours unlawfully. I was suffocated by a police officer because I resisted arrest. That’s because I was so indignant, I wouldn’t go to the police station. They put cuffs on me and I was treated like a criminal. Thrown in the back of a van and put in a cell for six hours. I was pacing up and down. I was treated like an animal, and then I was told I couldn’t see my mother for three months. I lost three months of my mother’s life because of them. And for something I never did!

Like many other families caught up in COP proceedings, Caroline emphasises the central role that “family” plays in vulnerable people’s lives. “Can we stress in your piece that social services need to listen to the families. That’s what I want to get out of this. They need to listen and understand that we have their best interests at heart. We know the person better than anybody else – certainly better than social services that just poke their noses in and misinterpret.”

And she points to the high cost of court cases (the first hearing, she says, cost the family nearly £10,000 as they tried – and failed – to get a legal team on board to represent Mrs P instead of relying on the Official Solicitor):

“Don’t forget to put something down about taxpayers’ money: what a waste of taxpayers’ money all these cases are. Must be half a million spent on this case I would think. They could be funding her care instead of ridiculing a family that have gone above and beyond the call of duty to look after Mum and saved her life, numerous times, all of us. I’ve loved, protected, and adored my mother. I’ve given up my life to look after her. And more than most people, well, we most probably are too close, but it’s just the way we are, and I just can’t believe what other people do and get away with and I get shamed for doing this. I had to save her life in that wretched hospital and it’s just so hurtful that they call what I’ve done “abuse”. My mum means the world to me. That’s why I did what I did and I’d do it again. I’d walk over hot coals for my Mum. Everything I’ve done – I’m really proud in a way – I’ve given my Mum three extra years of life. She’s alive and she’s at home and she’s got a life that I tell you now, she wouldn’t have without the intervention of me and my strong family. We have been there – me and [my partner] and my dad, we’ve been by her side, we have done everything for my mum. She knows that deep down.”

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin, on LinkedIn and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

Footnotes

[1] There is no restriction on the publication of Caroline Grady’s name – but we are prohibited from naming other family members (and this accords with their wishes).

[2] When two legal teams turn up in court to represent P”; “Complex issues for the court and plans for an ‘omnibus’ capacity hearing” and “Let us be alone as a family again”: An application for unsupervised contact at Christmas”

[3] In Re SA (2005) EWHC 2942 (Fam), Munby J held that, even if a person does not have an impairment of mind or brain, the inherent jurisdiction can be used in relation to an adult who is unable to protect themselves from harm because (for example) they are subject to coercion or undue influence and therefore disabled by another person from making a free choice. That decision affirmed the existence of the “great safety net” of the inherent jurisdiction (a term coined by Lord Donaldson in In re F (Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1) in relation to all vulnerable adults.

[4] The family are angry that the fact-finding preceded the capacity determination (by a few days), but I cannot see that it would have made any difference to the outcome whether capacity-determination or fact-finding had come first. In my view, the finding that Mrs P has capacity to make her own decisions about contact is all the more compelling for incorporating into the capacity assessment the findings of the negative impact of the mother/daughter relationship on Mrs P. Mrs P was aware of her daughter’s “brutish” behaviour and (the judge found) could weigh it in the balance when considering contact, and still capacitously wishes to spend time with her daughter. A capacity assessment which did not take into account the “facts” of the mother/daughter relationship (as determined by the judge) would have been open to challenge on the grounds that capacity to remain in an “abusive” relationship has to include the ability to understand, retain and weigh the abuse and its consequences.