By Daniel Clark, 13th November 2024

Headlines in 2016 described the Court of Protection as a “most sinister” and “most secret” court. It ‘left a 94-year-old without savings or dignity’.

Looking back from the perspective of 2024 at the early years of the Court of Protection (since its modern incarnation in 2007), it is clear that it’s come a long way in its approach to open justice.

In a series of decisions made in 2014-2017 by Sir James Munby, the-then President, the Court of Protection became much more open and transparent.

It is now common practice for cases to be heard in public (subject to a Transparency Order). Where a judgment is not published (which is still usually the case) members of the public or journalists who have observed the hearings are still able to report on it.

These reports can usually identify public bodies involved in the case, as well as the judge, the lawyers and the expert witnesses. Sometimes (though not often) we can also identify the protected party (P) and/or their families.

However, the judicial aspiration for transparency is not always met. Even when it is, it is not always clear what authorities the judges and lawyers are appealing to.

This research project

The Open Justice Court of Protection Project wanted to understand what guides judges’ decision-making about issues relating to transparency and open justice. What rules, Practice Directions, and case law is there? When can we be legitimately excluded from hearings (or part of them)? How can we be confident that we should be able to name a public body, and how can we make that argument if we meet resistance?

What is the decision-making process if the protected party, or their family, want to be named in reports of hearings? And from an equally important perspective – how does the Court protect the privacy of the protected party (and their family) and what can we do when it fails?

A requirement of my PhD funder, the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities (WRoCAH), is that I undertake a Researcher Employability Project (REP). This is separate from the PhD itself, and the idea is that I complete a research project with an external (non-university affiliated) organisation.

The stars, one could say, aligned. WRoCAH approved my placement with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project (22 days for 2 days a week) and I started working on this project from July 2024. A requirement of a REP is that there is some form of tangible output. One of these outputs is this blog. (Another blog, about access to physical courtrooms, is forthcoming.)

This blog will be divided into 6 parts. In section (1), I give a brief history of transparency (or not) in the Court of Protection. In section (2), I address the fact that, unlike many other decisions the Court makes, the decision to make a hearing public or private, or to name a public body, is not a best interests decision. It is a decision reached by weighing Article 8 and Article 10 rights – a balance that is thrown hugely off kilter in closed proceedings. Three pivotal issues relating to transparency and open justice are then highlighted: in part (3) identifying public bodies; in (4) identifying P, and in (5) identifying P’s family. Finally, I will discuss in section (6) how P’s right to privacy is sometimes breached not by public observers, but by the court. I end with some “Final Reflections’.

1. A (brief) history of transparency

It’s fair to say that the Court of Protection used to have, and for some still does have, a bad reputation on the transparency front.

Concern about ‘a forced caesarean birth’ and the imprisonment of Wanda Maddocks (who removed her dad from a care home against court orders) paved the way for the Daily Mail to campaign to open up the Court of Protection.

In November 2015, the Daily Mail declared ‘victory’: the Court of Protection would ‘throw open their doors at last’ in a six-month transparency trial, starting in January 2016.

For its part, the Court had been concerned with ‘a need for greater transparency’ for some time. In January 2014, Sir James Munby (the then-President of the Family Division) had signalled that he wanted to take ‘an incremental approach’ to transparency.

First, he wanted to see more judgments being published[i]. Then, he would issue more formal Practice Directions (which guide how practice should be undertaken in the Court of Protection), and then there would be a change to Rules.

A roundtable held in 2014, at the University of Cardiff, was influential in guiding the implementation of this Pilot. Mr Justice Charles, in a judgment handed down in a case usually referred to as “Re C”, set out detailed expectations for the Transparency Pilot. This began in 2016.

The intention was for feedback to be gathered on the experience of holding hearings in public but, according to the Court of Protection handbook, no such exercise ever took place. Instead, the Pilot was repeatedly extended until public access was incorporated into standard practice when new Practice Directions took effect on 1st December 2017. From then, transparency and open justice was the order of the day.

The doors of the Court were open but the public and the press weren’t frequently coming through them. In fact, it’s still quite rare now to see members of the press in hearings. The Daily Mail may have campaigned for greater access to the court but they don’t make much use of that today.

Then, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic happened. The work of the court did not stop – in fact there was an increase in applications during this time. Mr Justice Hayden, by then the Vice-President of the Court of Protection, issued Guidance on 31st March 2020 making explicitly clear that the court could sit remotely, and how that could work. Reading this document is a disconcerting experience. The world being described, one of lockdowns and restrictions on free movement, is both like something from a history book and something that happened yesterday. The judge was clear that the move to remote hearings does not mean that the public should be excluded from hearings. In his words: ‘Transparency is central to the philosophy of the Court of Protection. Whilst it will be difficult to ensure that a Skype hearing is as accessible to the public as an ‘Open Court’, this does not mean that transparency can become a casualty of our present public health emergency’.

Celia Kitzinger attended the first entirely remote Court of Protection hearing (on Tuesday 17th March 2020). She was supporting Jill Stansfield, who at the time had to be identified under a pseudonym (“Sarah”). Her father, who can now be identified as Brendan Atcheson, was the protected party. Mr Justice MacDonald reported that the feedback from this hearing was ‘universally positive’. It would appear, however, that he didn’t think to ask Jill or Celia what they thought. In the words of Jill (writing then as “Sarah”): “It felt like a second-best option. It didn’t feel professional. It didn’t feel like justice. It felt like a stop gap to ensure a box was ticked – rather than a serious and engaged attempt to make decisions about my Dad“.

To his credit, MacDonald J revised his initial report, adding that ‘it is important to note, however, that feedback provided by a lay party in the proceedings provides a significant counterweight to the foregoing positive assessments, and points up important matters to which those conducting remote hearings, and those participating in remote hearings should pay careful regard’.

With remote hearings becoming the norm, Celia Kitzinger and Gill Loomes-Quinn co-founded the Open Justice Court of Protection Project on 15th June 2020. The Project sought to support the judicial aspiration for open justice, alerting lawyers, judges, and HMCTS to barriers to transparency (such as inadequate case listings). It also shines a light on the work of the court, by encouraging members of the public to observe hearings and blog about what they see.

2. Not a best interests decision: Private hearings, closed hearings, and public hearings

Three rights are engaged in considering whether a hearing should be public or private: Article 6, Article 8, and Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights. No right takes automatic precedence over the other and, indeed, many complement each other.

Article 6 concerns the right to a fair trial. As with the other Convention rights, it is a qualified right. The relevant parts read as follows: ‘[…] everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law. Judgment shall be pronounced publicly but the press and public may be excluded from all or part of the trial in the interests of morals, public order or national security in a democratic society, where the interests of juveniles or the protection of the private life of the parties so require, or to the extent strictly necessary in the opinion of the court in special circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice’.

I have only found one instance when the Court of Protection has sat in private ‘in the interests of […] national security’. This was when the court considered (and ultimately approved) an application to allow further testing of Sergei and Yulia Skripal, who were exposed to a Russian nerve agent.

Private hearings

Private hearings are heard from a default position that members of the public and press are excluded, though in fact they can be admitted at the judge’s discretion. Ordinarily there is a total reporting ban, but an observer can apply afterwards for permission to report on particular issues.

Practice Direction 4C (Transparency) sets out the exact reasons why a judge may decide to sit in private. These are strictly limited reasons, as follows:

(a) the need to protect P or other people involved in proceedings;

(b) the nature of the evidence;

(c) whether earlier hearings have been in private;

(d) whether the court location has the facilities to allow general public access;

(e) whether there is a risk of disruption if the general public have access;

(f) whether, if there is good reason to deny access to the general public, there is also good reason to deny access to ‘duly accredited representatives of news gathering and reporting organisations’.

I think some of these reasons lack a certain reflexivity. For example (c) could well create justification for later hearings to be heard in private simply because somebody, at an earlier stage in the case, had failed to draw up a Transparency Order. In that situation, a case would become private by default, and not because of an express order from a judge (for two examples, see: “A private hearing before DJ Glassbrook” and “Can the court require certain information to be reported and specific words to be used as a condition of publication about proceedings?”)

Nevertheless, this is a useful list for understanding when a judge might be minded to make a hearing private. Until recently, however, there was no such (public) guidance for closed proceedings.

Closed hearings

Unlike private hearings, which all parties are expected to attend, closed hearings are held when a judicial order excludes a specific party (and they may not even know that the hearing is happening). These tend to be heard without the press or public present[ii].

In cases such as these, other hearings may continue with the participation of the otherwise excluded parties but they do not know what is happening in these closed hearings or even that they are taking place – as happened in the proceedings recorded as Re A (Covert Medication: Closed Proceedings). In that case, “A” was removed from the care of her mother and placed in a care home. Here she was supposed to be receiving medication that would commence a delayed puberty. “A” was reported to be refusing to take her medication, and it appeared both to her mother and to public observers that she wasn’t receiving it. Until, that is, Mr Justice Poole disclosed that, in parallel closed proceedings, HHJ Moir (by now retired) had authorised the use of covert medication. This was done without the knowledge of “A”’s mother or her legal team.

The court can also authorise the use of closed materials: when a specific party will not have certain materials shared with them (see, for example ‘A ‘closed hearing’ to end a ‘closed material’ case’). The first reported time that the Court of Protection considered withholding materials was in RC v CC & A Local Authority [2013] EWHC 1424 (COP). In this case, a birth mother (RC) wanted to reintroduce indirect contact with her adopted daughter (CC), who was 20 at the time of the application. HHJ Cardinal considered whether documents disclosed to RC should be redacted or unredacted (where the latter would reveal CC’s whereabouts). While the judge did not consider that RC would “act improperly in abusing such information [say in an attempt to trace her]” (§33), he nevertheless decided it was strictly necessary to withhold disclosure – and also limited disclosure of some evidence to the birth mother’s Counsel alone.

In February 2023, after the Open Justice Court of Protection Project raised serious concerns about closed hearings and their impact on transparency in relation to the Re A case, the then Vice-President of the Court of Protection, Mr Justice Hayden, issued guidance on closed hearings. This makes it clear that the starting point must always be that all parties can participate fully but this can be diverged from when it is necessary to secure P’s Convention rights or there are ‘compelling reasons for non-disclosure’ (such as the wider public interest). The decision to hold closed hearings is a case management, not best interests, decision.

I have not found many judgments that relate to closed proceedings or closed materials. There are, however, two things to point out. First, the Open Justice Court of Protection Project blog index has many examples of closed material and closed hearing proceedings[iii]. Second, it would appear, these proceedings only disadvantage family members. I have found no recorded instance of a public body being the excluded party.

Public hearings and the Transparency Order

Article 8 and Article 10 are the rights that should be balanced when formulating Transparency Orders but, as Celia Kitzinger points out, we know they are actually being drawn up as boilerplate documents rather than as a result of anxious consideration. Regardless of this, these are the rights that are engaged (even if a judge doesn’t properly acknowledge this).

Article 8 rights concern the right to respect for private and family life. Again, this is a qualified right. As the Convention puts it, there will be no interference by a public authority in the exercise of this right ‘except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others‘.

Article 10 rights are the right to freedom of expression, which includes the freedom to hold opinions, and to receive and impart such opinions or information without any interference by public authority. This is also a qualified right. In the words of the Convention, ‘the exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary‘.

When the court has decided that a case should be heard in public, a Transparency Order restricts information that can be communicated about the case. The ‘standard’ form of the Transparency Order is here: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/cop-transparency-template-order-for-2017-rules.pdf. This is a legal Injunction, breach of which may be contempt of court, resulting in a fine, having your assets seized or being sent to prison.

The Information that you cannot communicate (listed in §6 of the standard form of the Order) has the overriding objective of protecting P’s (Article 8) privacy. However, it is worth noting that it only protects P’s privacy in relation to the court case. It would not prevent somebody from writing, in detail, about P’s life. They just couldn’t mention the fact that the person is or has been a protected party. The Information usually includes anything ‘that identifies or is likely to identify’:

- P as the subject of proceedings

- Members of P’s family

- Where any of these people live or are cared for, or their contact details.

The category of P’s family is usually undefined and, therefore, very broad. This means that certain members of P’s family may be prohibited from talking about the fact that their (for example) cousin was involved in a court case. What is the likelihood that they would know an injunction prevents them talking about the court case? And is this really just?

Sometimes, a public body is also included in this list of prohibited ‘Information’ (I will discuss this in the next section). Other times, treating clinicians and care companies are included. Save for exceptional circumstances, the rule is that expert witnesses should not be included in this Information.

When a person is alleged to be in contempt of court, and committal proceedings are commenced, the general rule is that the person alleged to be in contempt (the alleged contemnor) is publicly identified. Court of Protection Rule 21.8(5) states that the court can decline to identify a party “if, and only if, it considers non-disclosure necessary to secure the proper administration of justice and in order to protect the interests of that party or witness”.

This does not extend to protecting the interests of a party other than those of the alleged contemnor (e.g. the protected party at the centre of proceedings). Since the alleged contemnor is often a family member of P and not infrequently shares their surname, there are ongoing concerns that naming alleged contemnors in Court of Protection proceedings risks identification of the protected party – a concern which may in fact have been at the heart of the contempt of court proceedings in the first place.

It is worth noting that there are some anomalies and inconsistencies between the COP rule and the Lord Chief Justice’s Updated Practice Direction: Committal for Contempt of Court – Open Court (March 2015)(see the analysis in Esper v NHS NW London ICB (Appeal: Anonymity in Committal Proceedings).

It is within the court’s power to restrict the publication of any information relating to a case. However, as Mrs Justice Roberts put it in Re BU, “the court cannot and should not make reporting restriction orders which are retrospective in their effect” (§109).

That being said, the standard Order has effect “until further order of the court”. This means that family members have to apply to the court if they want to speak openly about their family’s involvement in a court case, even after P has died. I struggle to see how an open-ended order is compatible with Article 10 rights. The Supreme Court is expected to express a view on this when it hands down judgment in Abassi and Hasstrup. These are two cases, joined together on appeal, that pose the same question: was the Court of Appeal right to discharge all reporting restrictions concerning the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment from two children?

Every so often, members of the public have received a Transparency Order that includes P’s full name either on the face of the Order or in the file name. Sometimes, the prohibited Information (such as the care home at which P resides) is not anonymised in the Order. This is a flagrant breach of P’s privacy. Nevertheless, some lawyers don’t see the problem with this: when we raise it with them, they tell us that there isn’t a problem because we are bound by the Order anyway.

However, it has been clear from my research that, from at least 2017, it was the intention that Transparency Orders would be anonymised. Mr Justice Charles (the then Vice-President of the Court of Protection) published an amended version of the original Transparency Order. There is no ambiguity: the face of the Order should include ‘the initials chosen to identify P’ and the parties should appear ‘in appropriately anonymised form’. The rationale is emphasised in the Court of Protection handbook, which states:

‘The Transparency Order is a public document and therefore P’s full name should no longer appear in full in it. Likewise, the names of the parties should be ‘appropriately anonymised’; although as with judgments public bodies should normally be named in full. except where naming the public body could give rise to ‘jigsaw identification’ of P’ (§14.26).

It’s this issue of jigsaw identification that I will now consider.

3. Identifying public bodies

Local authorities, NHS Trusts, and Integrated Care Boards are all public bodies. They are all funded by taxpayer money, and the taxpayer has a right to know how that money is being spent. As Mr Justice Keehan put it, in Herefordshire Council v AB (a Family Court case), ‘the public have a real and legitimate interest in knowing what public bodies do, or, as in these cases, do not do in their name and on their behalf’ (§50, my emphasis).

On very rare occasions (such as in the Re A case discussed in the previous section), a public body is not identified because of a risk of jigsaw identification. In A Local Authority v The Mother & Ors (another Family Court case), Mr Justice Hayden explained the meaning of jigsaw identification like this: ‘The potential for jigsaw identification, by which is meant diverse pieces of information in the public domain, which when placed together reveal the identity of an individual, can sometimes be too loosely asserted and the risk overstated. As was discussed in exchanges with counsel, jigsaws come with varying complexities. A 500-piece puzzle of Schloss Neuschwanstein is a very different proposition to a 12-piece puzzle of Peppa Pig. By this I mean that whilst some information in the public domain may be pieced together by those determined to do so, the risk may be relatively remote. The remoteness of the risk would require to be factored in to the balancing exercise when considering the importance of the Article 10 rights’ (§18).

It is now generally the case that the Court of Protection permits the identification of public bodies. In fact, it is such common practice that judges don’t really comment on it unless they are making a decision the other way; that is, that they are choosing not to name a public body.

At the time of writing, the most recent example of this is A Local Authority v ZX. The issues that the case concerned were ‘extremely disturbing’ (in the words of HHJ Burrows), and the judge was concerned that identification of the local authority would pose a significant risk of jigsaw identification. Indeed, the facts of the case (as set out in the judgment) are so singular that I can see how the judge reached that conclusion. HHJ Burrows was however keen to publish a judgment so that the public could still scrutinise ‘the judicial process and the conduct of the parties and others involved in litigation’ (a quote from Jack Beatson’s ‘The Rule of Law and the Separation of Powers’).

Concerns about jigsaw identification and the nature of the facts of the case persisted after the judgment was handed down. An appeal against the judge’s decision that ZX lacks capacity to engage in sexual relations was heard in public on 13th November 2024, but not (as is common practice) live-streamed, although we know at least one member of the public attended in person, and two attended via remote link.

Sometimes public bodies do make arguments about a risk of jigsaw identification which are ‘too loosely asserted and the risk overstated’. On those occasions, members of the public have made applications to vary Transparency Orders (a right anybody affected by the Order has). The Open Justice Court of Protection Project’s blog index has many such examples[iv].

G v E & Anor (a case from 2010) is an important source for formulating basic arguments about the identification of public bodies. In this case, Mr Justice Jonathan Baker (as he then was) found that Manchester City Council had infringed P’s Article 5 (right to liberty) and Article 8 (right to private and family life) rights. The Council did not want to be identified in his public judgment; the judge found against them. He identified three salient factors: the size of the local authority can reduce the risk of identifying P; taxpayers need to know what is happening so that a local authority can be held accountable; and publicity can shine light on the issues that local authorities are facing in the implementation of their obligations (§16).

4. Identifying P

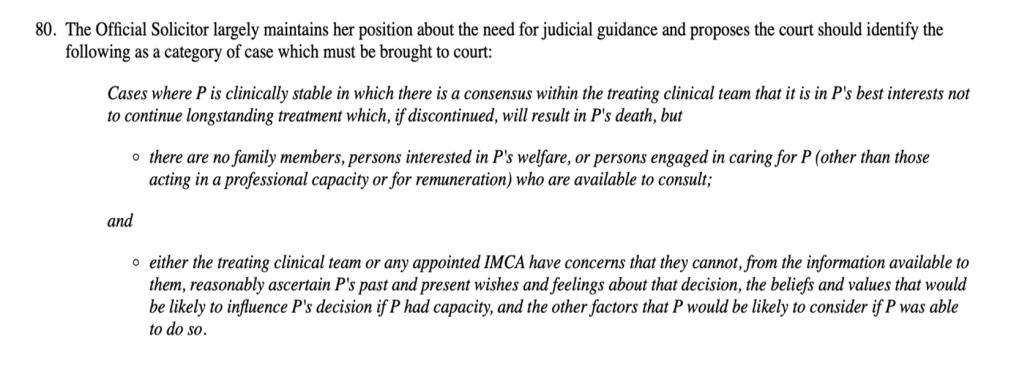

Unlike many other decisions the Court of Protection makes, the decision as to whether to name a protected party (or allow others to do so) is not a best interests decision. It is instead the weighing of Article 8 and Article 10 rights.

There is, in effect, a blanket ban on naming P. This is a default position that assumes, given the private nature of the matters before the court, that P would want to be anonymous and also that it is in their best interests to be anonymous. If someone wants to name P, or P wants to name her-or-himself, there is lots of protracted and anxious consideration of the matter.

In my research, I have identified twenty-one protected parties in the Court of Protection whose names have been published (in judgments) since 2009. These people represent a very small percentage of those who are actually “Ps”. One of the first was Steven Neary, who Mr Justice Peter Jackson (as he then was) found had been unlawfully deprived of his liberty by the London Borough of Hillingdon (§32).

On very rare occasions, some protected parties are named in published judgments without an explanation of why, and against the wishes of their family. This happened in a case concerning the withdrawal of clinically assisted nutrition and hydration (out of respect for the family’s wishes, who did not want P to be named, the hyperlink is to an open access paper which discusses the case but does not name P).

After the death of her father, “Sarah” (whose father was the protected party at the centre of the first remote proceedings of the pandemic), engaged in a lengthy but ultimately successful application to vary the Transparency Order. Her father can now be identified as Brendan Atcheson, and “Sarah” can now be identified as Jill Stansfield. Of course, Jill Stansfield is not the only person who has successfully applied to vary the Transparency Order. In essence, the arguments that families employ are that, since P has dead, she or he no longer has a right to privacy.

In another unusual case, the Court of Protection had treated Aamir Mazhar as a protected party. He was removed from his home after an out-of-hours application to the Court of Protection, and a Transparency Order prohibited his identification. However, it was subsequently found that he “has the capacity to make decisions about his life, including about his care and treatment” (§3). Aamir Mazhar chose to identify himself during (Court of Appeal) proceedings.

I stress, yet again, that these are unusual circumstances. Quite often, a judge will not vary a Transparency Order so that P can be identified even when P would like to be identified.

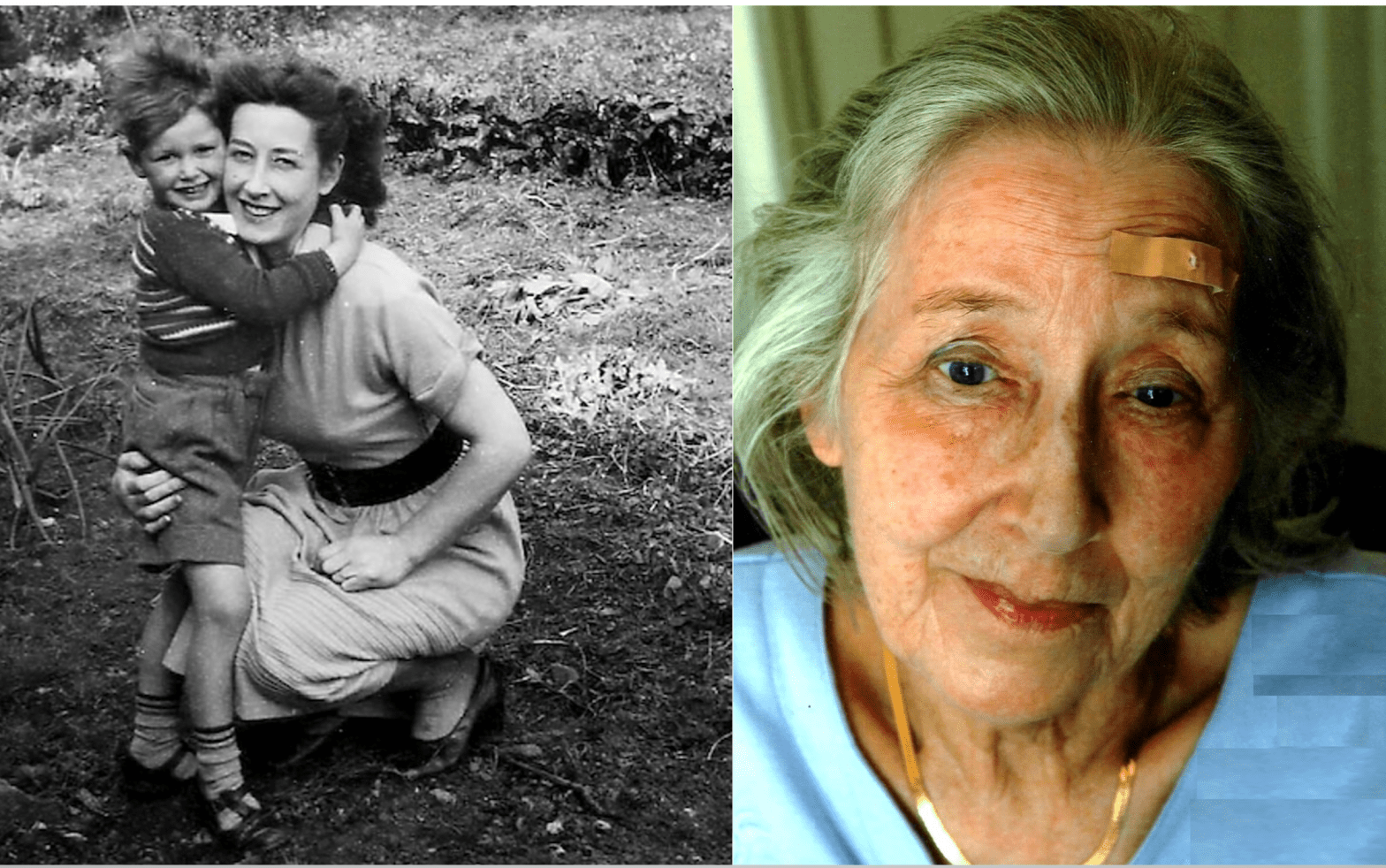

I’ve found four general overlapping categories of applications to name P in public: P has died; P wants (or would have wanted) to identify her-or-himself; the press wants to name P; P’s friends or family want to identify P. In my view, it is these last two categories that are the most common. The case of Manuela Sykes combines the two. Manuela Sykes was a former politician who was described in the judgment of DJ Eldergill as having, ‘played a part in many of the moral, political and ideological battles of the twentieth century’. She was a trade unionist, an advocate for the homeless, ‘and a campaigner for people with dementia, from which condition she now suffers herself’. At the time of the hearing (in 2011), she was living in a care home and objecting to her deprivation of liberty. She wanted to move back to her own home (which the judge authorised, albeit for a trial period that ended with her return to a care home).

The press wanted to name Manuela Sykes as the party to proceedings, and some of her close friends agreed they should be able to. As a result, the judge had to grapple with whether Manuela Sykes’s Article 8 right to a private and family life took precedence over the Article 10 rights of the press, and her family and friends. After a weighing exercise (which you can find in the published judgment), the judge found that there was ‘a clear public benefit’ in the publication of her name. This was supported by the fact that Manuela Sykes had been a life-long campaigner, and had been open about her diagnosis with dementia.

Sometimes, P’s family want to be able to identify P because there will be benefits to other Ps and other families involved in Court of Protection proceedings. Other times, there may be a tangible benefit to P. Jordan Tooke and William Verden were two young men who were in need of a kidney transplant. In both cases, their family applied to the court to vary reporting restrictions so that they could be identified. In being able to use their name and pictures, the families felt that this would increase the chance of finding an altruistic kidney donor.

Sometimes, reporting that precedes a Court case essentially means that “the horse has already bolted”. A Transparency Order prohibiting the identification of P would achieve very little. Andy Casey was a healthy young man who was assaulted in a pub garden. Testing confirmed that his brain stem had died (meaning he was legally dead) but his family did not accept this. The NHS Trust made an application to the Family Court for declarations that he was dead, and it was lawful for organ support to be withdrawn. Andy Casey’s family wanted his name to be known, and media reporting of the case prior to a judge making a Transparency Order meant that making one at the time of the hearing would have been entirely pointless. Though not heard in the Court of Protection (the Official Solicitor declined to act as Andy Casey was dead, and therefore did not have “best interests” in the legal sense of the term), the principles of transparency still apply. As Celia Kitzinger and Brian Farmer noted in a blog about the case, ‘there may be lessons here for families who want to speak out’.

Of course, not every application to be able to name a protected party is approved. In LF v A NHS Trust & Ors, Mr Justice Hayden considered an application by G’s father (LF) for the discharge of all reporting restrictions. LF said that this was so the family could start a GoFundMe page to raise funds for a new vehicle. On that occasion, the judge did not grant the application. While accepting that he was restricting LF’s Article 10 rights, he considered this to be ‘a proportionate and necessary intervention’ to prevent any attempt at disrupting P’s move from hospital to a care home. We blogged about this case a year later, when the court considered allegations that P’s family had tampered with her medical equipment.

When a judge authorises the identification of a protected party, it naturally follows that their family will also be identifiable. After all, the “jigsaw” becomes a lot smaller when you know a name.

5. Identifying P’s family

In Southend-On-Sea Borough Council v Meyers (a case heard under the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court), Mr Justice Hayden allowed the identification of Mr Douglas Meyers. However, Mr Meyers was keen to protect the privacy of his son, KF. The judge prohibited his identification.

What of families who do not want to be able to name P but do want to be able to identify themselves? This is the position of “Anna”, whose mother (who is still alive) was a “P” in a now concluded court case. You can read about it here: “‘Deprived of her liberty’: My experience of the court procedure for my mum”. “Anna” does not want to have to use a pseudonym but a Transparency Order prevents her from writing in her real name. She has written a blog about this situation. It is worth reading it in full but I have picked out a few paragraphs that succinctly explain the problem:

‘As part of the case, we had to confirm that we would comply with the Transparency Order (TO) issued as part of the process. This was a standard TO, typical of the one used in most COP cases (as explained here: Transparency Orders: Reflections of a Public Observer ). I didn’t hesitate to agree. As far as I was concerned, I could see the purpose of it, protecting mum’s privacy.

I didn’t foresee how much of a burden it would become, as I have wanted to share our story in order to raise awareness of the process, and so that other families can benefit from our experience. […] Now I find myself living in a parallel universe. In order to write and talk about the case, I had to create a pseudonym “Anna Jones Brown”. But, with my real identity, I’m not allowed to talk about it, or refer my friends and family to Anna’s activities, such as the blogs I have written or the Podcasts that [my sister] and I recorded with Clare Fuller (https://speakforme.co.uk/podcast N° 55, 56 and 57).

If you have read my blog or listened to the Podcasts, you know more about our experience than my family and friends do.’

It is not just “Anna” who wants to be able to identify herself, and the Project has blogs about other cases in which a family member has asked to be able to identify themselves (see, for example: “She wants to tell her Court of Protection story but will the court allow her?”)

This research project therefore incorporated what, if anything, case law has to say about family members who want to identify themselves but not P. I have only been able to find one such case. In what was a complete surprise to me, it was actually a judgment handed down prior to the Transparency Pilot. The case, Re M, concerned allegations that E, a mother, had imposed a factitious disorder on her son, M. Among other issues, the court was asked to consider an order that would prohibit M’s parents (E and A) from discussing the case with anybody other than their legal representatives.

Mr Justice Baker declined to make such an order. He said: ‘It is certainly none of my business what E or A do with the rest of their lives and I do not discourage them from publishing their experiences or views on the many issues that have arisen in this case’ (§43). This came with a catch, however. The judge prohibited the identification of the local authority, social workers, and any others associated with ‘the events of this case’. This was because ‘there is a significant risk that M could be identified because of the highly unusual facts of this case’. So, M’s parents could identify themselves but not M, his address, or the local authority.

This is by no means perfect. However, it is proof that it can happen. Judges can permit families to identify themselves while, at the same time, keeping P’s identity secret. Hopefully, this logic will be accepted so that “Anna”, and many others like her, can finally step from out of the veil of anonymity.

6. When P’s privacy is not protected

The steps towards greater openness and accountability in the Court of Protection are to be applauded. However, the court’s actions can (on occasion) infringe P’s Article 8 rights.

For example, P’s name (and even P’s address) has sometimes been posted in the public lists. When the Open Justice Court of Protection Project sees this, one of its core team contacts the court to alert them. As the lists are posted in the late afternoon/evening, the court office is usually closed by the time somebody sees the email. By that time, P’s name has been on a publicly accessible website (CourtServe) for quite some time.

As I discussed in the second section of this blog, Transparency Orders should not name the people whose identity is protected by the injunction. However, it is not uncommon for members of the public to receive a Transparency Order with P’s name on the face of the Order or in the filename. Recently, I received a Transparency Order that included not only P’s name but also P’s date of birth on the face of the order.

Several members of the public have received a “record of information” – essentially, a full list of the exact information that the Transparency Order prohibits us from identifying and which we might otherwise not have any access to (such as P’s address and telephone number and the home contact details of P’s family).

This seems difficult to square with the Court’s commitment to protecting P’s privacy. It is one thing to hear the name of a care home mentioned briefly during a hearing. It is quite another to be given a document that tells you exactly where that care home is and how to contact it. This may arise from confusion between a Transparency Order and a Reporting Restrictions Order but in “Re C” (referred to in section 1), Mr Justice Charles was clear that a Transparency Order (in the standard form) does not contain a schedule identifying those who cannot be identified (§195(i)).

It is also becoming quite clear that not all judges are giving anxious consideration to whether a case should be heard in public or in private. In pursuit of the appearance of open justice, it seems that some judges are automatically making hearings public (by authorising a Transparency Order) without any consideration of what would actually happen if a member of the public turned up to observe.

As Eleanor Tallon has detailed, when she asked to observe a hearing listed as a “Public hearing with reporting restrictions”, she was sent a link but on joining, she learnt that P was distressed at the thought of a member of the public being present. The judge therefore decided at that point to hear the case in private – which was a perfectly legitimate decision (though Eleanor goes on to say that the judge may have misapplied the Civil Procedure Rules). However, the case number indicates that this is a long running case and clearly nobody had thought to discuss with P the possibility of a member of the public being present until one of us turned up. Not discussing the possibility of an observer being present is, in my view, potentially harmful to P, as well as disrespectful. According to the Court of Protection’s own rules, there is a general expectation that P will be told about proceedings that concern them. Surely part of that discussion should include the possibility of a member of the public being there.

This is a concern that is also acknowledged in the Court of Protection handbook. Its authors write: ‘The [Open Justice Court of Protection] Project team and the observers who have sat in on hearings have asked searching and important questions about the practices and processes of the court. However, it is also legitimate to identify that facilitating that access has come at some cost in terms of the (scarce) resources of the court. It is also legitimate to identify that there are some situations in which insufficient focus has been paid to the impact upon P of (in effect) broadcasting – or at least, narrowcasting – a hearing‘ (§14.4, my emphasis). While this shouldn’t be taken as an appeal for more hearings to be made private, it is an issue that the Court needs to seriously grapple with.

There are some judges who have tried hard to strike the balance between privacy and open justice. For example, Mr Justice Poole recently informed “A” and her mother why members of the public were observing, and advised them to move two seats along. This gave them more privacy from observers, as they were now out of camera-shot, while also facilitating open justice.

One way for the Court to strike a balance between P’s privacy and its commitment to open justice (which are not always mutually exclusive) is – as both Poole J and Hayden J have done on several occasions – to hear an application for a private hearing in public court. That way, the public can make submissions themselves (such as suggesting other ways to safeguard P’s privacy that P may find acceptable). It would also be a clear signal that there’s no conspiracy in the decision to hear a particular case in private. Instead, it’s a result of the proper balancing of Article 8 and Article 10 rights.

Final reflections

The Court of Protection has come a long way since the damning headlines of 2016. Indeed, the general commitment to open and transparent justice is one that should be recognised and applauded. There are certainly lessons here that the Family Court should take careful note of.

I have no doubt that these moves to greater transparency have been assisted by the work of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. The work of the Project in educating and informing about the role of the Court, as well as alerting HMCTS to barriers to transparency, has greatly improved matters in this area.

In fact, it’s because it’s clearer how to obtain video links for Court hearings that more members of the public have observed hearings. In turn, this has created a need for judges and lawyers to further consider how to make hearings transparent in practice (rather than only theoretically so) such as ensuring that observers can actually see and hear the courtroom during hybrid hearings. Despite time pressures and resource constraints, HMCTS staff, lawyers, and the judiciary have worked hard to try to make sure that justice is being seen to be done. At the risk of stating the obvious, it would not be possible for the public to know about the work of the Court of Protection without their efforts.

Things are by no means perfect but it’s a vast improvement since 2020, let alone 2016.

This blog is a result of research conducted as part of a Researcher Employability Project (REP), which is funded by the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities (WRoCAH). Notwithstanding this funding, which only Daniel is in receipt of, the Open Justice Court of Protection Project retains editorial control over this blog. Furthermore, the views expressed in this blog are those of Daniel, and not those of WRoCAH. Further information about the REP can be requested by sending an email to openjustice@yahoo.com.

Daniel Clark is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. He is a PhD student in the Department of Politics & International Relations at the University of Sheffield. His research considers Iris Marion Young’s claim that older people are an oppressed social group. It is funded by WRoCAH. He is on LinkedIn, X @DanielClark132 and Bluesky @clarkdaniel.bsky.social.

[i] It is worth noting that the number of judgments published in the Family Court far outweigh the number of judgments published in the Court of Protection. This may be because cases in the Court of Protection more often conclude in agreement with no decision or judgment necessary, but experience invites me to believe that this isn’t the full story. I have observed a number of (sometimes contested) hearings, including before Tier 3 judges, where a “final judgment” was handed down but where no subsequent judgment was published.

[ii] As far as I know, I am the only member of the public who has been permitted to observe a closed hearing. I wrote about this fact, though not what actually happened, in this blog: “Closed hearings, safeguarding concerns, and financial interests v. best interests”.

[iii] For example

“A ‘closed materials’ hearing on forced marriage” by Celia Kitzinger

“Emergency placement order in a closed hearing” by Celia Kitzinger

“Closed hearings, safeguarding concerns, and financial interests v. best interests” by Daniel Clark

[iv] For example

“What to do if the Transparency Order prevents you from naming a public body” by Celia Kitzinger

“Prohibition on identifying Public Guardian is “mistake not conspiracy”, says Judge” by Celia Kitzinger and Georgina Baidoun

“Prohibitive Transparency Orders: Honest mistakes or weaponised incompetence?” by Daniel Clark

“Centenarian challenges deprivation of liberty – and judge manages transparency failings efficiently” by Celia Kitzinger

“My experience at Weymouth Combined Court: listing, access, and transparency” by Peter C Bell

“Judge approves P’s conveyance (against his wishes) to a care home – and tells lawyers to “just stop!” routinely anonymising public bodies in draft Transparency Orders” by Daniel Clark