By Claire Martin, 18 August 2024

This case (COP 13236134) has been in the Court of Protection since 2018.

The protected party (A) is a 25-year-old woman, who has been living in a care home under a Court of Protection order, for five years. If all goes according to plan, she will be back at home as she wants, living with her mother, by the time you read this blog. It’s been a long journey.

Background

She was initially removed from her mother’s care and placed in a care home on 9th April 2019 in the hope that, away from her mother’s influence, she would agree to take hormone therapy for Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. She did not.

Then, all contact with her mother was stopped in June 2020, after the court determined that her mother’s influence was the reason for her refusal. But still she continued to refuse to take the medication.

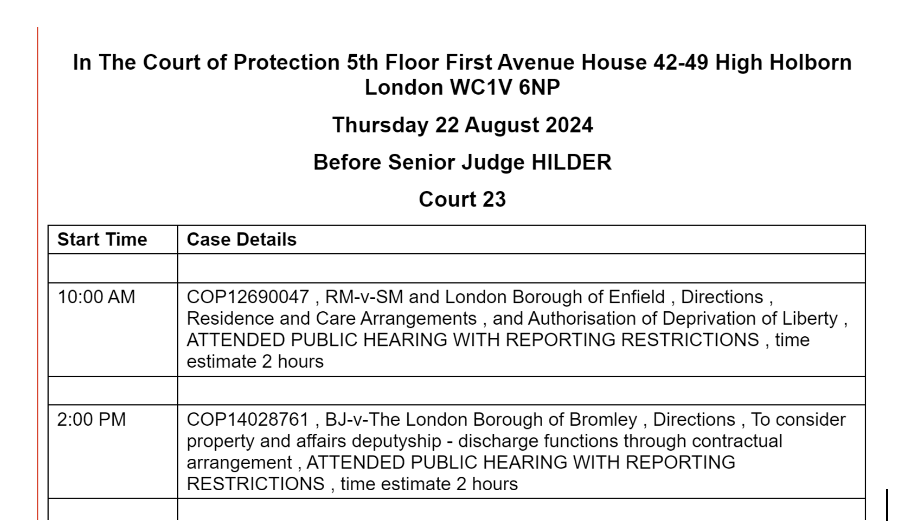

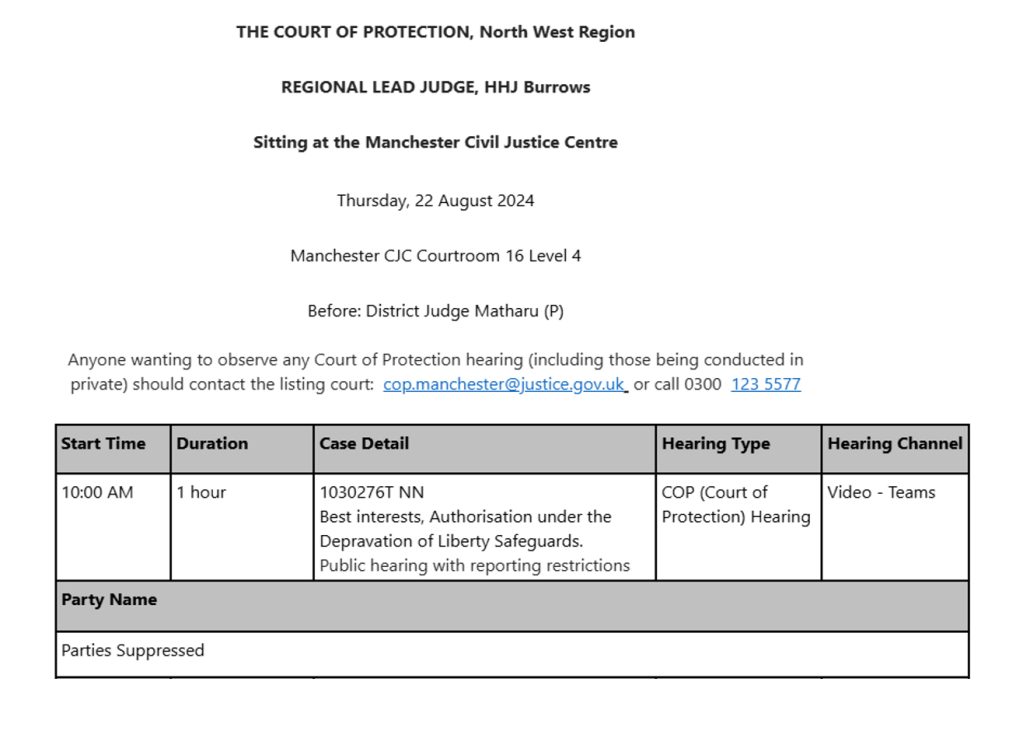

What happened next was shocking for those of us following the case. The judge (HHJ Moir) heard the case at a closed hearing – that is, a hearing from which the judge deliberately excluded A’s mother and her legal representatives. A’s mother was not informed that the hearing was taking place. At that hearing, HHJ Moir authorised covert medication for A, so that she would go through puberty, The judgment from that hearing is publicly available here: A Local Authority v A & Ors [2020] EWCOP 76). I don’t know whether there was any public listing of this hearing – quite possibly there was not. Certainly, public observers were not aware it was happening and the judgment was only made public (by Poole J) years later at our request.

In April 2022, A’s mother (B), believing that A had still not received the hormone medication (the reason she had been removed from her care) and, of course, not having seen her daughter since June 2020 – if she had done so, and seen that her daughter had gone through puberty, she would likely have raised questions about that – applied to the Court of Protection for her daughter to return home.

I observed a hearing for the case on two days in April 2022, before HHJ Moir, and blogged about my confusion that A had apparently been in the care home for two years yet, the hearing led me to believe, had still not received the hormone medication.

Then, in September 2022, a three day in-person hearing was held, this time before Mr Justice Poole (a Tier 3, High Court, judge) who had taken over the case on HHJ Moir’s retirement. Daniel Cloake contacted us during the hearing to let us know what was going on – and later wrote about it: ‘“I have to tell you something which may well come as a shock”, says Court of Protection judge.’ At this hearing, Poole J revealed to A’s mother and her legal team – and to us as observers – that A had been covertly medicated for two years and had now achieved puberty. Nobody had yet informed A, and she was continuing, daily, to refuse the medication, and then, daily, to be covertly medicated.

This case shook our faith in open justice in the Court of Protection. We felt we had been misled by the court (as had A’s mother and her legal team) about what had been going on. We had also published an inaccurate and misleading blog post because of this, which Poole J acknowledged in his published judgment, while recognising that we published in good faith based on the information provided in court (Re A (Covert medication: Closed proceedings)) 2022 EWCOP 44) . We expressed our own concern about the effect of this on open justice and transparency in a blog post here.

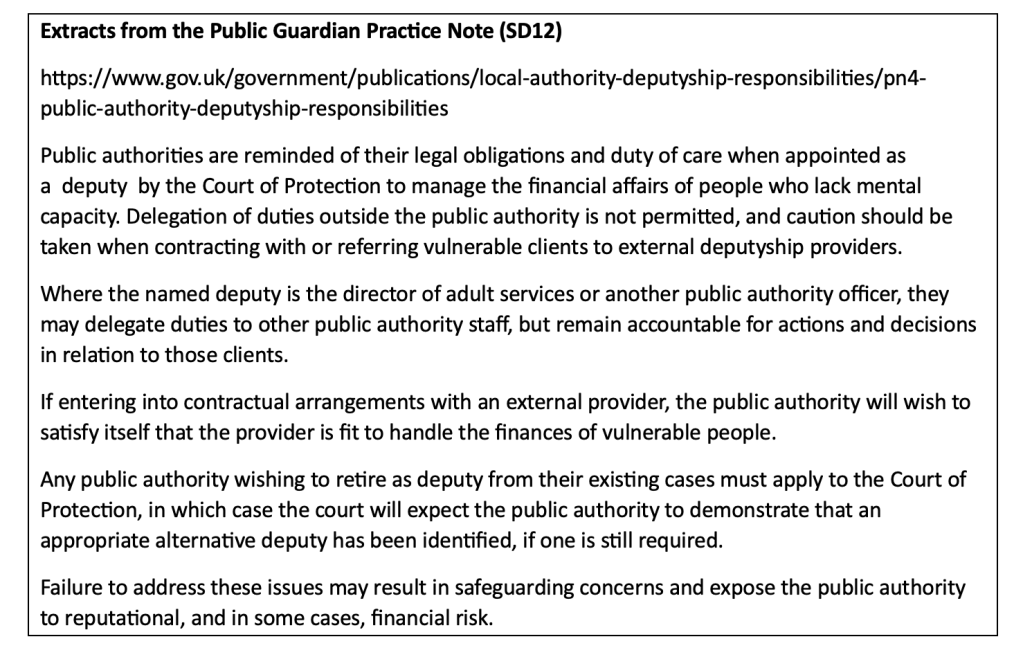

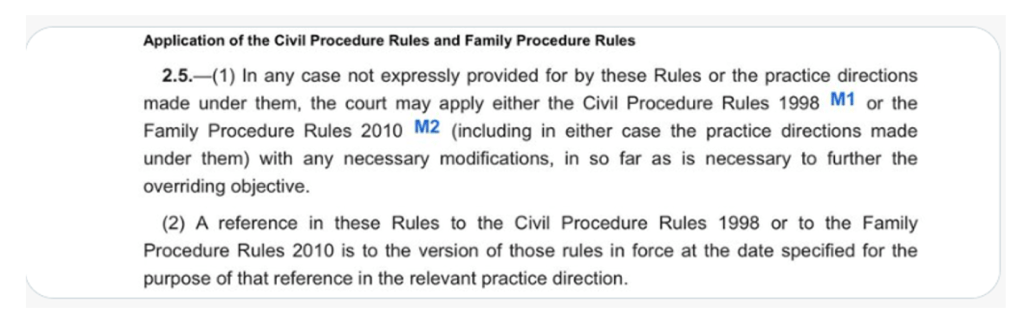

In the wake of this case, and our public reporting of it, the COP set up a sub-committee of the Court of Protection Rules Committee to review the matter of Closed Hearings and to produce some Guidelines.

Celia Kitzinger made a submission to this group on how closed hearings are conducted and the impact on transparency and public trust in the courts. (Closed Hearings: Submission to the Rules Committee). New guidance was published and although the situation with regard to closed hearings has improved somewhat, we are concerned that there are still unresolved problems which are not being addressed.

Following Mr Justice Poole’s laudable decision to stop the closed hearings, members of the public observed a series of subsequent hearings in 2023 and 2024 at which attempts were made, in effect, to unpick the mess this case had by now become, by sorting out an “exit plan”, which seems not to have been contemplated at all in the original decision to covertly medicate A. The “exit plan” from covert medication would, the judge suggested (repeatedly), involve informing A that she had achieved puberty as a result of being given the hormone medication without her knowledge, and covert medication would then stop. It was hoped (perhaps unrealistically under the circumstances) that she would voluntarily take the ‘maintenance medication’ that continues to be prescribed. Finally, there was also the matter of authorising A’s ‘exit’ from the care home. The main reason she was there was for covert medication. Once this ended, that justification ceased – and since both she and her mother wanted a return home, there was a strong argument for her to be discharged into the care of her mother. Our blog post covering these issues is here: “Still no exit plan and ‘we are some way from the ideal scenario’”

Subsequently, following a hearing we didn’t observe in January 2024, Poole J made a decision that it was in A’s best interests to return home, whether or not she voluntarily agreed to take the hormone treatment: Re: A (Covert Medication: Residence) [2024] EWCOP 19. He also said that covert medication should cease.

The hearing was in response to B’s renewed application for her daughter to return home – supported neither by the local authority (which instead suggested a change of residence for A from the care home to independent supported living, although without a concrete proposal in hand) nor by the Trust nor by the Official Solicitor. In the judge’s view, although it might be possible for medication to continue to be administered covertly whilst A remained in the care home, or in independent supported living, she might discover that she’s being covertly medicated at any point. The plan, he said, “is fraught with risk … I doubt that it is sustainable for years ahead” (§ 52 : Re A (Covert Medication: Residence) [2024] EWCOP 19). He also found her mother’s proposals to encourage A to take medication voluntarily to be “unrealistic” (§ 53). The full judgment is worth reading for its careful and unflinching analysis of the issues in this case. Here are some key extracts:

§58. … it is a significant infringement of A’s human rights to medicate her against her wishes and without her knowledge. Presently, the provision of covert medication requires her to be deprived of her liberty, to live away from home, and for her contact with her mother to be regulated. Whilst she would no longer be deprived of her liberty if she were to return home and contact with her mother would no longer be regulated in the same way, continued covert medication in the community would still be a significant infringement of her autonomy and Art 8 rights. Hormone treatment is good for A’s health, but it comes at a heavy price in terms of infringements with A’s human rights.

§59. I have to consider the length of time over which these very serious interferences with A’s human rights may continue. Dr X’s evidence is that it is in A’s medical best interests to continue to receive hormone treatment for the rest of her life. Therefore, I have to contemplate the possibility of A being deprived of her liberty, covertly medicated, and separated from her mother whether in a care home or in SIL [Supported Independent Living], for the rest of her life. In nearly five years since A was removed from her mother’s home no-one has persuaded her to take HRT voluntarily. Even now, it is proposed that further strategies are deployed to try to persuade her. Whilst it is understandable that attempts should continue, in my judgement the time has come to acknowledge that such attempts are unlikely to succeed. A has been remarkably consistent and tenacious in refusing HRT. Nothing that has been attempted – removing her from home, suspending all contact with her mother, providing information and education, building her trust in her carers – has made any difference. It is more in hope than expectation that new strategies are now suggested…

§66. I have not been provided with any plan for the transition of residence, the ending of covert medication, or the imparting of information to A about covert medication….

§70. A return home to the care of her mother, will expose A to a substantial risk of harm flowing from the nature of the relationship between her and B. This enmeshed relationship previously resulted in A being deprived of medical attention and treatment that she required, reasonable medical advice regarding A being rejected, and significant social isolation. Under B’s care A was under-developed physically and mentally, and was ill-prepared for independent or even semi-independent living. There is nothing in the evidence I have seen or heard to lead me to believe that there will be a marked difference in B’s approach to her relationship with A were A to return home. B may have learned to say some things that she knows she ought to say to portray a more positive future for A at home, but I have no sense that she has any real desire to change. She gave no impression that she thinks she has ever done anything wrong.

§72. I have focused on the negative aspects of A and B’s enmeshed relationship but there are some positive aspects. There is a bond of love between them. A strongly wishes to live with B…..

§80. The relationship between A and B is deeply troubling and has caused significant harm to A, but her relationship with B and with her grandmother is the family life that A knows and to which she strongly wants to return. Some measures can be taken, in A’s best interests, to try to protect her from the most harmful aspects of her relationship with B, but it must be accepted that returning A home will remove a layer of protection that she has benefited from within the placement. However, if A’s enmeshed relationship with B prevents it being in her best interests now to reside at home, it is unlikely that it will ever be in her best interests to reside at home. It is difficult to see how their relationship will change. Hence, if A does not return home now, she may very well be accommodated away from home, separated from her mother, against her strong wishes, for the foreseeable future. The influence B has over A has apparently survived all attempts to dismantle it over the past few years. It is entrenched and cannot be wished away. Realistically, it is too late now to try to undo all the harmful effects of the relationship. The best that can be done is to try to mitigate them in the future.

Having made this decision, Poole J gave directions to the parties to provide evidence to the court as to the planning for A’s return home, the cessation of covert medication, and the provision of information to her

The judge fixed a one-day hearing for 18th April 2024 at which the detailed arrangements were to be determined, but everything then stalled because the judgment was appealed by the Trust and the Official Solicitor.

It was heard in the Court of Appeal on 30th April 2024 and Poole J’s judgment was upheld. You can watch the Court of Appeal case on YouTube here: Re: A (By Her Litigation Friend, The Official Solicitor) and the judgment is here: Re A (Covert Medication: Residence) [2024] EWCA Civ 572 Lord Peter Jackson, who wrote the Court of Appeal judgment says that Poole J:.

“… grasped the essence of this complex and concerning case and he appreciated that A’s situation cried out for a definitive decision. Wherever she lives she will suffer harm and gain some benefit, and a move home in the face of deep professional scepticism could only take place with a firm judicial lead. The judge might have followed the professional advice, but he explained why he did not. He might have approved a trial at home (though it seems in some respects the worst of all worlds) but he did not do that either. Instead, he reached his own conclusion, based on his considered assessment of A’s best interests, supported by coherent reasoning. For what it is worth, I find his analysis strongly persuasive.” (§110)

The hearing I am reporting on for this blog followed the Court of Appeal ruling that upheld Poole J’s decision.

The hearing on 24th June 2024

The hearing on Monday June 24th 2024 was an ‘implementation hearing’ – for the court to decide how the court orders (upheld by the Court of Appeal) should be put into effect.

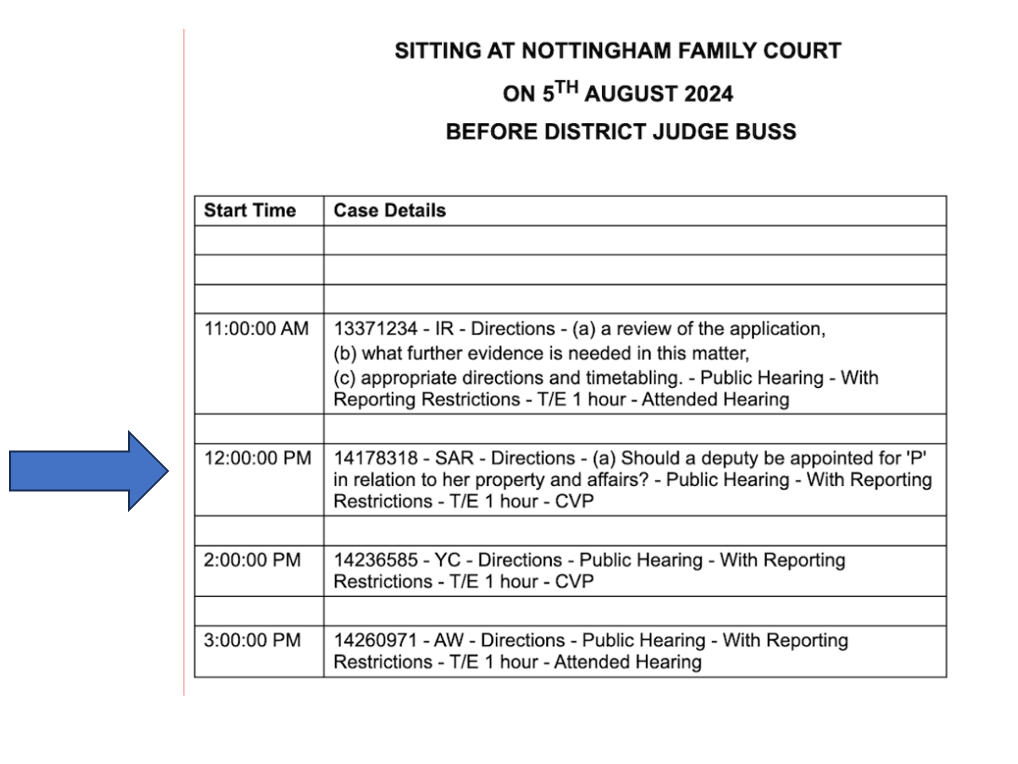

I observed it, along with a clinical psychology trainee, in-person in Middlesbrough. I have blogged about the observation experience separately because this was only the second hearing I have observed in person and the process was exemplary in terms of public access and transparency.

In this post I will outline the issues before the court at this hearing, describe in some detail Poole J’s directions and the micromanagement into which he was being invited to engage by the parties. I’ll outline how the court handled differing positions from the parties on what to tell A about the ‘truth’ of what has happened. I will end with some reflections on the case.

Issues Before the Court

After a helpful brief summary from Katie Gollop KC (counsel for the Local Authority – LA) -as requested by Poole J who noted that there were ‘two observers in court and one online’ – counsel for the LA outlined the ‘outstanding issues’ for the court[1]:

- Disclosure – “if she asks why, what should she be told?” [i.e. if A asks why she has been covertly medicated, what should she be told?]

- Timing of the return to her mother’s care – “how close to the provision of information [should this happen]? Should the provision of information be in stages (A has a short attention span) or should it be in one go?”

- A’s access to the consultant treating endocrinologist – “A’s mother continues to object to being in the same room because of trauma around the Irish accent.”

- Community access – “[this] is chicken and egg – the LA haven’t been able to recruit carers without a start date. A potential care provider has been identified, they want to do their own assessment, they are willing to come forward without a start date. It is a matter for you My Lord about how much oversight – how often she’s offered a trip and what to do”

- Access to WiFi – “A spends a lot of time on her tablet – the placement says she spends most of waking hours watching videos on YouTube, not emailing or accessing social media, but watching YouTube channels. If she goes home tomorrow there is no WiFi at home, so there is an issue there as to that being sorted out.”

The parties seemed to be asking for extremely detailed directions from the judge about how to execute the ‘exit plan’.

The morning part of the hearing: “I am not going to descend into that kind of detail” Poole J

The judge described his expectations for how the court orders should be implemented:

“[The] principles: all these arrangements are designed to put into effect the decision of the court earlier this year. [They] must be in A’s best interests and it is in her best interests to serve her autonomy and to protect her from the risk of harm that flows from returning home. There is no perfect solution in this case and whichever way one turns there is a balance of benefits and harms. The risk of harm upon returning home needs to be mitigated and arises from the enmeshed relationship with her mother, and from the risk she will not continue to take HRT. […] I shan’t reiterate all the considerations from the judgment earlier this year. Also, the risks to her from causing distress to A, sudden changes she doesn’t understand. In relation to the first issue of disclosure, I have already decided that she should be given truthful information about what has happened during the course of this case. She will be told that the decisions to remove her from her mother’s care and to start covert medication were decisions of the COURT, not decisions of her mother or health care professionals, but of the court, and it won’t be helpful to provide her with all the judgments, but it might be helpful to have a letter from me to A, and a separate letter to her grandmother, or in similar terms to Whoever it May concern, set out in short form, about decisions made.

That she was unaware of covert medication, and the fact that these decisions were decisions of the court and why they were made. They will include the recordings that were made by Judge Moir that […] her mother had not encouraged, and in fact had actively discouraged, A from taking HRT and that this is a matter that her mother now regrets. This also gives the court an opportunity in the letter to emphasise the benefits NOW of taking HRT and to emphasise that the court from a certain point does not permit any further covert medication, to reassure her that that is stopped.

I have seen the planning documents about disclosure of information and careful thought through language and images which I think is excellent. As a point of fact, I don’t mind a picture of me, but not as the judge who decided covert medication, but as a matter of fact it was a different judge. I hope I’m not being defensive. It is a matter of fact.

It seems to me unnecessary for information to be given at a neutral venue. I see no reason why it can’t be given at a place where A has lived now for a number of years. I don’t see any added benefit to moving to another venue. It should happen in a natural way. Bearing in mind A and her impairments, it seems perfectly sensible to break down the information in stages, I suggest by the LA, so that in a short .. matter of days only …. Day 1, ‘the judge made decision that she should return home, BUT there should be further discussion before the moves takes place’; day 2 have the discussion with the LA as to the history of the court’s decisions and the administering of covert medication, and from that point there shall be NO FURTHER covert medication, and she shall be told this. It’s important that she is enabled to trust that covert medication has then ceased. Given the evidence … rapidity about stopping HRT … [it] might be best to have conversation after her meds that day. Day 3: any questions, day 4: transfer home.

[Regarding] provision of information, I agree with the LA plan. The main individuals will give this information to A and then her mother will be able to speak to A, given that A is going to return home to her mother’s care, and clearly there is not going to be monitoring of every conversation they have, so it seems to me better that they have that conversation in private. Her mother has assured me she is going to encourage A to take the HRT, and I take that on trust. The fact is that she will be living at home.

The Day 1 conversation is ONLY about residence and […] her mother needs to be involved in that. It might be better on that occasion for her mother to be with others. I accept that this is a managed process. The provision of covert medication cannot be undermined. I envisage that with some arrangements that have to made – community care, WiFi – the sequence of events will begin within a fortnight, if not tomorrow.

So far as Dr N (endocrinologist) is concerned – the ‘phobia’ [about Irish accents] that A has, cannot come from A’s own experiences. It must have come from her mother who has that phobia. The fact is that A has … doesn’t want to have dealings with Dr N. We have to work around that. It seems sensible that a GP … can oversee the administration of HRT… if that’s what she chooses to do. [They] will still need consultant guidance and reviews from time to time, bone density scans etc. At some point a consultant will have to be identified. It’s best just to accept that it’s not in her best interests to force Dr N … I accept there’s a limited number of specialists available.

The community access plan – A does not now access the community with any great frequency. It might be best to accept …. once a week, rather than three times a week. It’s a matter for her and her carers – she needs to exercise her autonomy as best she can. The tablet issue – if there’s no objection from her mother to having WiFi in the home, that can be arranged. Her mother will have to help A balance her time with the use of devices and other activities.

The grandmother: it seems to me that after A has been told about covert medication and that it is stopped and encouraged to choose to take it herself, it’s a good time for her grandmother to also be told what has happened. Her grandmother might be a good source of support to encourage A to take it. [Poole J: judge’s emphases]

I thought Poole J was very clear in his directions for the exit plan.

There was discussion about the fact that it is, now, going to be A’s choice whether she takes the HRT. Although it is more protective of her long-term health for her to continue to take the medication, the risks to her health (of not taking the maintenance HRT) are said to be less than had she not gone through puberty at all. There is further information on Primary Ovarian Insufficiency treatment here.

On balance, Poole J has decided that A’s best interests are not served by achieving treatment covertly, which would require her to live apart from her mother – a situation that, over the past five years, has caused A significant distress, and continues to do so, to the extent (it was said) that she rarely leaves, or engages in anything within, the care home.

This is clearly not what was anticipated when HHJ Moir made her judgment in 2019. The situation that the court and the system around A had embroiled themselves in, and which Poole J was attempting to disentangle them from, reminded me of the quote from Munby J, in 2007, in this case (§120): “What good is it making someone safer if it merely makes them miserable?”

Joseph O’Brien (council for the NHS Trust) made – I thought, given the history of the case – a curious request regarding the judge’s letter to A:

“The Trust is concerned about building up trust with A. We would encourage you to encourage A to trust the doctors. We would implore that the letter sets out she should listen to the doctors.

J: She may not listen to me, but I will draft letters and I am able to take on board suggestions.”

Commentary on the morning: Trust and Attachment

A has spent the past five years, removed from her mother’s care (where she has consistently stated she wants to be), and has not been persuaded to trust doctors. She is now going to be told that doctors – authorised by the court – have been prescribing and secretly crushing up tablets in her sandwiches. And at the same time the judge is being asked to tell A to trust the doctors. It might be objectively true that continuing to take the HRT will be helpful for A. It is also objectively true that ‘doctors’ (in the form of the proxy care home) have been deceiving A for many years. A is offered the HRT every day – and every day she refuses – and as far she is aware, her decision has been respected. This adds another, daily, layer of deception. Now she is going to learn that she has been deceived, not only about taking HRT medication, but also that she has been led to believe that her decisions have been respected, when they have not.

The original Local Authority plan in 2019, outlined by HHJ Moir in her judgment, states:

§13. Within the plan, the local authority sets out at E12: “The primary reason for A’s proposed move to residential care is to address concerns related to her health and wellbeing. A is likely to need a period of sensitive, tailored emotional support to enable her to come to terms with a move to residential care as she is opposed to this plan currently. The move may be experienced as traumatic and distressing. A referral to health agencies who can provide psychological support will be considered as needed. A has significant health needs associated with epilepsy and primary-ovarian failure. She has been resistant to treatment plans, particularly in relation to the latter diagnosis. The aim of the plan is to provide a supportive, engaging environment where A’s understanding of the benefits of treatment and her compliance can be promoted more effectively.”

In 2022, when the case came before Poole J, the judgment stated:

§20.The evidence demonstrates that A is clearly benefiting from her residence at Placement A, both as a result of the support and care she is receiving, and the medication administered to her. She is enjoying benefits for her physical and mental health. Dr X reports that her socialisation and behaviour have improved “gratifyingly”. [Dr X is an endocrinologist expert witness].

I would be interested to know the nature of the ‘sensitive, tailored emotional support’ that was offered to A. It isn’t detailed in the evidence (that I can find) in subsequent documents (to the 2019 judgment) about the case, and by 2024 any improvement in ‘behaviour and socialisation’ seemed to have faltered.

Attachment, separation and loss were the focus of Bowlby’s studies in the 20th century on the vital importance of human relationships for psychological health. He defined attachment as a “lasting psychological connectedness between human beings.” There is a huge body of research about attachment (and of course scholarly criticism too). This is a good primer, if you are interested. Having observed three of the hearings for A’s case, having the benefit of some of the parties’ Position Statements and reading the judgments in this case, I am persuaded that neither the strength of A’s attachment to her mother, nor the potential damage from suddenly removing A from that relationship, have been appreciated by the court until this year.

A paper on security and separation, by Stroebe, a well-respected loss and bereavement researcher, states – referring to attachment theory:

“A basic fascination about the theory—one which also made it remarkable when first published—lies in the fact that it can explain health difficulties which are not originally caused by physical or medical conditions: simply being harshly separated from (or bereaved of) a close person can cause mental and physical health problems (even—though rarely—mortality from a broken heart).”

The Court of Appeal judgment includes a transcript (§33) of a conversation (this year, five years after she moved to the care home) between A and her solicitor (which vividly conveys A’s feelings for her mother and level of trust she has in doctors):

“Sol. How many times are you having contact with mum?

A. Twice a week. (sobbing) I want more time.

Sol. Do you think your mum is encouraging you to take your

medication?

A. It’s my choice and she knows it so she doesn’t push it. I trust

my mother.

Sol. You say you trust your mother. She is working with the court

and she wants you to take it because she knows it’s safe and

you need it.

A. She won’t force me because it’s my body.

Sol. If you trust your mother why won’t you trust her and take the

medication.

A. I don’t know, I guess I’m just nuts, aren’t I?

Sol. I don’t think you trust your mother.

A. Hey hey HEY I do trust my mother, don’t say I don’t trust my

mother.

Sol. If you trust her you should trust that she wants the best for you.

A. No matter what, I will never believe or trust any of you.

Sol. We have sought you an independent expert to clarify your

diagnosis, but will you engage with them.

A. No because I will never trust one of you. Let me go home and

I will choose one myself out the phonebook when I am home

not someone connected to you.

A. (Sobbing) I’m in hell. It’s not that hard to see anyone working

with you. I know you will have paid [them] off to say what

you want.

Sol. This is not the case A. We are all working together to try and

find a conclusion to this.

A. Yeah, rubbing your hands together taking all the money.

A. I want someone I can trust.

Sol. If they give you the same diagnosis will you trust them then?

A. I don’t know do I, as long as [they’re] not connected to you.

Sol. So a Dr not connected to Dr X giving you the diagnosis

wouldn’t help?

A. No, I will only listen to someone I find myself from the phone

book when I am at home.

Sol. Ok, I will let the Judge know that.

A. I have had enough, shut up.

Sol. Is there anything else you would like to tell the court.

A. Just fucking cork it.

Sol. Ok [A] – as you know the hearing is at the end of this month

and I will let you know the outcome. Bye.

A. Just fuck off.”

My one comment on the tenor of that conversation is that I think the solicitor is rather provocative (“I don’t think you trust your mother”). If the aim was to develop trust in ‘the system’ around A, that approach is unlikely to be successful.

Given this current stalemate, it also seems unlikely to me that A will respond to a letter from the judge saying ‘trust the doctors’ by simply acceding to this entreaty. Will she even believe that the covert medication is stopped, and that it is, really, her decision whether to continue HRT? I think there could be a risk that she doesn’t, given that she has been led to believe it has been her decision each day for the past five years, has believed she is making that choice, and will learn that she has been wrong in that belief. Might she think that somehow, some way, the medication is still being secreted into something else she is eating or drinking? Part of me wonders why the court didn’t simply authorise covert medication – arguably, appearing to give a choice has the potential for later reducing trust, compared to never having had a choice at all. Learning what has happened could cement (rather than diminish) her lack of trust in the health and care system. I am not suggesting that she should not be told, but that the system has potentially created future risk, which could possibly have been foreseen and better managed with some credible work on ‘exit plans’ far earlier in the process.

During the lunch break the parties worked on the draft order to bring to the court in the afternoon session. When the court reconvened, it became clear that the parties’ positions were still some distance apart.

The afternoon part of the hearing: What is the the ‘truth’?

Michael O’Brien (counsel for ‘B’) started by taking the judge through the implementation order, which included telling A about what had happened. But he pointed to “a matter of contention” between the mother and other parties as to the truth about what, in fact had happened. The order stated that A should be told that HHJ Moir said that her mother “discouraged” her from taking HRT and now regrets that. But Michael O’Brien wanted the order to be amended to say that HHJ Moir found that her mother “did not encourage” A to take HRT and her mother now regrets that. Poole J was firm:”But you just said that it should be what the court found. HHJ Moir found that it was active discouragement. That is what was found. […] Please don’t meddle with the words. You cannot pick and choose the words. That was the finding of the court. I am not sure why we are having this debate.” [judge’s emphasis]

A ‘fact’ found in a Court of Protection case cannot be altered and must be treated as a ‘fact’ in subsequent hearings and court orders (unless the Court of Appeal or Supreme Court overturn it) – regardless of the views of those who might think those ‘facts’ are incorrect.

This particular tension was about whether A’s mother actively discouraged A, rather than simply failed to encourage her, to take the HRT medication. HHJ Moir (the original judge in this case) had found, as fact, ‘active discouragement’.

Poole J referred to the original judgment (18th June 2019) and clarified that HHJ Moir had judged:

§88 “Sadly, I find that B has been so obsessed with her own wishes, views, and fears that she is being blinded to the obvious and risk-free advantages to her daughter of encouraging her to undergo the treatment and has, instead, failed to encourage her daughter to engage with the treatment or has actively dissuaded her daughter from doing so. Thus, the prospect that B will in the future support her daughter and positively encourage her to engage with the treatment must be extremely limited. Sadly, it is difficult to reach any conclusion other than B would prefer A not to “grow up” for want of a better description, that she would prefer A to remain the same, dependent upon her mother, and isolated within her mother’s sphere without any outside influence or interference.”

The judge also addressed the suggestion that his letter would be the sole information imparted to A: “and I‘ve said my letter may assist but it’s not a substitute for the information”. [judge’s emphasis]

I made a note to myself during this part of the hearing to the effect that counsel for B appeared mightily fed up with the LA and NHS – this impression was based on his exasperated tone of voice and overall demeanour. (I imagine that feeling, if I am correct, was reciprocated). Somehow the parties in this case have become so dug into their trenches that it seems almost impossible to come up for air. There is very little trust between them, it seems.

This exchange illustrates the situation. Counsel for B is explaining that, whilst on the one hand, the mother was being charged with a caring responsibility for A, the LA was declining to provide her with information about their plans for taking A out into the community:

Counsel for B: As far as community access is concerned, with LA Support Workers. There is an issue here. To date we have been unable to get anything from the LA about what would happen when support workers take A out into community. At the advocates meeting [we were] told that’s not a matter for [A’s mother] to know. That it’s a matter between A and the support workers. Well, [A’s mother] does need to know, she needs to support A to go out, so she needs to know what A is going to be doing when she goes out. The difficulty here is that there is, as My Lord is well aware, there is every attempt [….] every attempt she has tried to engage, she has been rebuffed. So, it is clear from the first day that she is supposed to go out with support workers. A’s mother wants to do that. As far as [her mother] is concerned, what is important is that she knows what is going on so she can encourage her to go out. [She] agrees that there should be a session every week to go out, [she’s] content to encourage more than that. She can’t find out what is planned, [there is] no clear plan from LA. There is reason to be sceptical…

The LA position (as presented by Michael O’Brien, the mother’s counsel) was that going out and about was a matter for A and her carers, and nothing to do with A’s mother. I thought this seemed unrealistic – especially given that (it was said) A has not been ‘out in the community’ for the five years she has resided at the care home. I also wondered whether A wants to go out with support workers. The conversation transcript with her solicitor (above) makes me think she’d rather have nothing to do with anyone from the state system at all! There might be lots of contributory reasons for this – including what the court is describing as an ‘enmeshed’ relationship with her mother – but the reality of A’s sense of the world and her relationships is what it is.

As Poole J previously stated “[t]here is no perfect solution in this case and whichever way one turns there is a balance of benefits and harms.”

Nevertheless, the judge instructed “I said that it should be for A and the support workers, precisely to enhance A’s autonomy. In the context of the sometimes-harmful relationship which crushes A’s autonomy. However, the support workers should communicate with her mother about plans for outings so she knows what’s happening.”

Counsel for B said “I am grateful. That is very clear.” He went on to say (later) “The reason I am being so pedantic is because I know that with the LA, unless it’s clear, the LA will ask for more and this will cause negativity”.

Poole J: “… the whole discussion rather speaks to a breakdown of trust”.

It did indeed appear that way.

Counsel for the mother was painting a picture of a Local Authority taking every possible opportunity to shut A’s mother out of her life – under the guise of enabling A’s ‘autonomy’. Counsel for the LA did not comment further, though had clearly stated at the start that they did not trust A’s mother to be as good as her word.

There was a final discussion about the draft order, agreements between the parties and the level of input from Poole J into this process. It was interesting to observe the parties and the judge involved in something of a dance about who was to take most responsibility:

Counsel for the LA: […] the LA plans are best interests informed documents, [A’s mother] has been very frequently consulted, but in the end …. unless your lordship wants to be the arbiter….

Judge: You can tell I don’t, but I will see the final order.

Poole J asked for a review hearing to be listed for October 2024. The LA had ‘pencilled in’ a review hearing for December 2024, explaining: “[The] only problem is [it’s] going to take time to commission Support Workers”. I was a bit confused by this, because A’s return home was planned for the next week or so, at which point (I thought) the Care Plan was meant to be implemented.

Nevertheless, Poole J suggested: “Let’s be optimistic […] in time for a hearing in October, December is too far off.”

Final Reflections

My overwhelming feeling at the end of this hearing was one of sadness. I fully understand why the NHS Trust and the LA, both charged with a duty of care for looking after A, took the action that they did, back in 2018, of applying to the Court of Protection to establish whether A had capacity to decide her medical care, and if not to determine her best interests.

As the Court of Appeal said:

“§10. It was by that stage established that A has the following life-long conditions: Mild Learning Disability (IQ 65); Autistic Spectrum Disorder (‘ASD’) – Asperger’s Syndrome; Epilepsy; Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (‘POI’); and Vitamin D deficiency. Taken together, these conditions render A an extremely vulnerable person, physically, psychologically and socially.”

§15. Judge Moir’s reasonable prediction that B’s negative influence on A would diminish with separation and time has sadly been disconfirmed by the events of the last five years.”

I wonder how HHJ Moir came to that ‘reasonable prediction’? I have read the judgments and although A was seen by an Educational Psychologist and a Consultant Psychiatrist, I didn’t read (in the judgments) any evidence presented about clinical approaches to ‘enmeshed’ relationships and how, carefully, to address problems arising from them. A focus on the HRT issue seems to have completely outweighed everything else, including any psychological understanding of the impact of sudden separation and limited contact with the key person in her life.

The psychological concept of ‘enmeshment’ originated in structural family therapy theory. This website asks: What is enmeshment trauma? and provides this answer: “Family enmeshment occurs when a family lacks clearly defined roles and boundaries. Salvador Minuchin first described the concept in his structural family therapy theory, which emphasizes the role of family relationships in an individual’s ability to function. According to Minuchin, enmeshed family members struggle to define themselves outside the family. They have high levels of communication and little physical and emotional distance.”

In an article (2004) called ‘Family Systems Theory, Attachment Theory, and Culture’, the authors take a cross-cultural approach: “Family systems theory and attachment theory have important similarities and complementarities. Here we consider two areas in which the theories converge: (a) in family system theorists’ description of an overly close, or “enmeshed,” mother-child dyad, which attachment theorists conceptualize as the interaction of children’s ambivalent attachment and mothers’ preoccupied attachment …..We also review cross-cultural research, which leads us to conclude that the dynamics described in both theories reflect, in part, Western ways of thinking and Western patterns of relatedness. Evidence from Japan suggests that extremely close ties between mother and child are perceived as adaptive, and are more common, and that children experience less adverse effects from such relationships than do children in the West”.

It might be accurate to describe A and B’s relationship as ‘enmeshed’ for our culture, though a psychological diagnosis such as this is not helpful without a full exploration and understanding of the reasons for, and the likely success or impact of, any actions subsequently taken to try to undo the ‘enmeshment’.

A has spent five years separated from her primary ‘attachment figure’ and the information I have read would suggest that she had, previously, developed very few other relationships, excepting her grandmother and a friend she describes as the daughter of her mother’s friend. Reading the Court of Appeal judgment, it is hard not to form the view that A seems to be more psychologically disturbed now and is consistently expressing distress at the lack of contact with her mother. The one thing that has been achieved has been (covert) HRT to induce puberty.

Throughout the hearing, A’s mother was looking down at and fiddling with her hands quite a lot. She looked very nervous. She was on her own at first, sitting in the dock until Poole J entered the court and said to her: “You are sitting in the dock! Is there somewhere else you can sit?” She was sitting at the back behind counsel and their solicitors, behind a glass panel, all on her own. She laughed nervously and moved to sit next to people I think were solicitors at the side of the court.

She did not visibly respond when people mentioned her ‘enmeshed’ relationship with A, or the risk of ‘harm’ to A from her maternal relationship. It must have been hard to listen to. I kept thinking – perhaps it is a relationship that has meant that A is unable to separate emotionally from her mother – that might not be the ‘best’ thing for her (or anyone, especially in our culture), but there are many relationships that mirror this co-dependence. Telling A that it is ‘rational’ to take the medication, go out with support workers, or (as counsel for the NHS Trust suggested) for the judge to tell her, in his letter, that she must ‘trust the doctors’, is simply not going to work for a person who has spent most of her life living in a bubble with her mother.

The past five years of forced separation have not affected her willingness to ‘enhance her autonomy’, go out with support workers, or indeed, voluntarily take the prescribed medication. It seems to me to be unrealistic and reveals a lack of psychological understanding to expect A to achieve autonomy at home, when the system itself has completely failed to make any headway in this respect when she has been away from home – for a five-year period. It is almost as if she is being expected to develop MORE autonomy at home than she has done at the care home, and A’s mother is being expected to create a willingness in A (to be autonomous), that her mother – probably for her own personal, historical reasons – does not want to happen. No one (it seems) at the care home or in the wider system of support for A has managed to do this.

Is the system setting up yet another situation that is likely to be unattainable?

We are all of us formed and influenced by our upbringing, main caregivers and culture. Jehovah’s Witness children, as a result of their upbringing, grow up with a belief that receiving blood products is wrong, and we all form beliefs and views that lead us to act in ways that others might deem unwise and against our ‘best interests’. And as long as our capacity is not in question, we are allowed to make these decisions.

I do not have direct first hand knowledge of whether A lacks capacity for the decisions before the court. Given that the witnesses at the first hearings had differing views about A’s capacity for medical and care decisions, this could be considered a ‘close to borderline capacity’ case, although the court has since found, after very careful scrutiny, that she lacks that capacity. In hearings we’ve watched as part of the OJCOP Project we’ve often heard judges say that the closer someone is to retaining capacity for a decision, the less likely they feel they should make a decision that runs counter to what the person says she wants. In this case, a decision was made counter to her wishes – principally due to the (understandable) medical concern that A was pre-pubertal and the significant health risks that carries for an adult woman.

I think my feeling of sadness about the case comes from stepping back and looking at what the outcomes of the early closed hearings before HHJ Moir have achieved. They have brought about a positive outcome (A has achieved puberty) but also created harm, for the people involved: A’s distrust of doctors and carers has been massively reinforced; staff have been ‘enmeshed’ in lies and deceptions; lawyers are frustrated with the situation and apparently with each other; parties are asking the judge to micromanage a case they feel is out of control following a judicial decision they don’t like and tried to appeal. Relationships are strained).

If judges are going to interfere with people’s lives – separate them from the people they love, order them to be given secret medications they have refused – they need to be sure that the positive outcomes outweigh the negative ones. Hand on heart, can we say that of this case?

I hope that A and her mother can re-establish a life together, and that A can develop a sense of what she wants over time and be compassionately supported to live her life happily – even if it’s not in a way that other people think is ‘normal’.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

Appendix

Previous blog posts about and published judgments from this case

In reverse chronological order – start with the blog at the bottom to read ‘from the beginning’

The published judgments are:

[1] All quotes are as accurate as possible – we are not allowed to record hearings, so this report is based on typing as quickly as possible to capture what is said in the course of the hearing.