By Celia Kitzinger, 7th June 2024

We operate a “Watch List” at the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. We do this because the Court of Protection doesn’t always get things right first time around.

Sometimes we find repeated problems with how particular judges’ hearings are listed (e.g. they don’t have descriptors to tell us what they’re about, or they say “Private” when they’re almost certainly not). Or court staff at particular hubs or from particular courts recurrently fail to send us video-links in time to observe hearings. When this happens, we put the relevant courts, or regional hubs, or judges on our “Watch List”. This means we try to ensure that someone goes along to future hearings and raises concerns if the problems continue. We hope that by repeatedly alerting the relevant authorities to the fact that they don’t have it right first time around, they’ll do better in future. It seems to work. We review the “Watch List” each month – removing those who are performing better, and adding others who are cause for concern.

The South West hub (all of it!) has been on our “Watch List” for the last two months because it has a disproportionately high number of hearings listed as “Private” – and one particular judge in the South West hub, District Judge Eaton-Hart (who sits in Torquay) was on our “Watch List” for an additional reason – a history of listing problems (no descriptors, and no contact details).

So, I watched two of DJ Eaton-Hart’s hearings in May – and having done so I added DJ Smith (who sits in Plymouth) to the Watch List. That’s because at both of DJ Eaton-Hart’s hearings I was sent Transparency Orders made by DJ Smith, and both were problematic. I subsequently sought to observe two of DJ Smith’s hearings. Both were vacated – but I was sent the Transparency Orders for both. So, this blog draws on the four (sealed) Transparency Orders made by DJ Smith[1] that I was sent in connection with hearings during May 2024 to show how, as a member of the public, I was able to support the court’s learning about transparency.

As I’ll show, the first three Transparency Orders I was sent took up a fair amount of court time because they (erroneously) prohibited reporting of the identity of public bodies. On the first two occasions, I challenged the Transparency Orders via an email addressed to the judge, leading to what he described (several times) as a “learning experience”. On the third occasion, I challenged the Transparency Order via a formal COP 9 application. The fourth Transparency Order didn’t need challenging: it didn’t prohibit reporting the identity of any public bodies. So it looks as though the “learning experience” had worked.

Of course, I am pleased that DJ Smith (and DJ Eaton-Hart and probably quite a few other judges whose Transparency Orders we’ve challenged) are now more aware of the requirements of open justice and how Transparency Orders should work. But I’m also concerned, that this may not be the most efficient and cost-effective way of imparting this information.

I’m told that a message has now been sent (by the Senior Judge? by HMCTS?) around the South West hub (and maybe further afield?) telling judges not to routinely anonymise public bodies. It would of course be much better for everyone if these errors were not made in the first place – but where they have been made, I would hope that they might be spotted in advance by lawyers or by the judge and fixed before the Transparency Orders are sent out to us.

At the moment the court seems to rely on members of the public to spot the errors and to ask for changes. This does not seem an efficient or sensible use of public funds, and it places the burden of open justice on the shoulders of members of the public who are not trained in law, and do not necessarily have the knowledge or skills – or confidence – to carry out this task. Correcting erroneous Transparency Orders also involves quite a lot of court time and imposes an unnecessary burden on the public purse.

Here’s what transpired with some of DJ Smith’s Transparency Orders during May 2024.

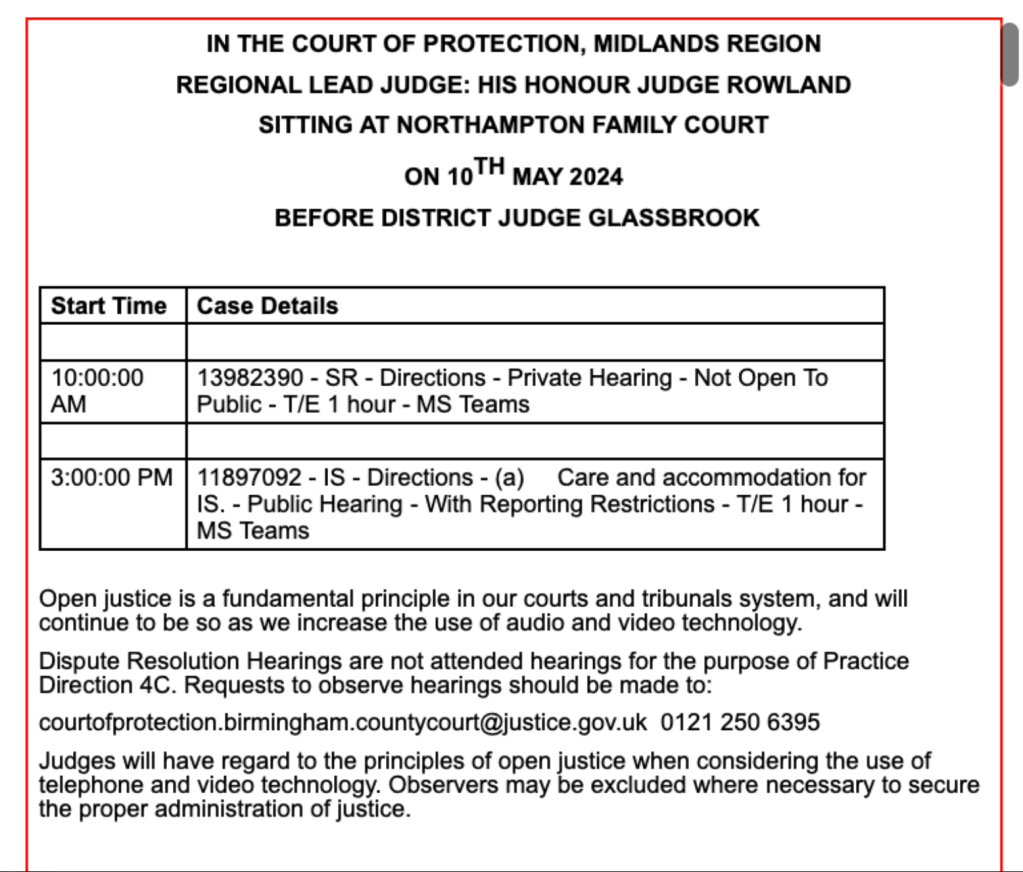

DJ Smith’s Transparency Order No. 1: Received 15th May 2024

The first hearing I observed before DJ Eaton-Hart was on 15th May 2024 and he’d “inherited” a Transparency Order from another judge, DJ Smith. There’s nothing unusual about that. It’s often the case that Transparency Orders are simply “carried forward” from one hearing to the next, even when there’s a change of judge.

But the Transparency Order for this case (COP 14203764) prohibited us from identifying the Local Authority (Devon County Council) – and also named P on the face of the Order, in the file name, and in the body of the Order itself.

There was no reason to anonymise the Council (or to name P in the Order) and I complained about it to DJ Eaton-Hart, who asked for it to be changed. I wrote about it here: “Centenarian challenges deprivation of liberty – and judge manages transparency failings efficiently.

Then, two days later, the same thing happened again.

DJ Smith’s Transparency Order No. 2: Received 17th May 2024

On Friday 17th May 2024 at 8.17am, I asked to observe all three hearings listed before DJ Eaton-Hart that morning.

I heard back at 10.36am that the 10am had been vacated, and the 12noon was likely to be vacated too – but the 11am (COP 1424179T) would go ahead and the court staff sent me the link and attached the sealed Transparency Order.

I saw immediately on opening the Transparency Order that, just as before, there were problems. The protected party’s (P’s) name was on the face of the Order and in the file name – though not, on this occasion, in the body of the Order itself (where the initials “TA” were used). And the Order prevented reporting the identity of the local authority.

As before, the Order had been made by DJ Smith, sitting in Plymouth and not by DJ Eaton-Hart.

As I’d been sent the Order in plenty of time, I was able to write to the judge before the hearing started – which is much easier than trying to raise problems orally during the course of the hearing. Here’s what I wrote.

The judge was efficient and crisp in managing the problem.

At the beginning of the hearing, he referred counsel to “the Transparency Order on page 23 of your digital bundle” and pointed out that it named P: “it should clearly be anonymised”.

He continued: “Second, it injuncts those who are the subject of this order from identifying the local authority. This appears to be a boilerplate order that has come in with those two technical but important defects. It appears there has been no scrutiny of Article 8 and Article 10 rights nor is there any suggestion that this is one of those rare circumstances under which the local authority can be anonymised. Unless anyone seeks to persuade me otherwise, I require a new Transparency Order that doesn’t name P, and doesn’t injunct anyone from naming the local authority”.

The applicant lawyer said he didn’t believe he needed instruction from his client but would go ahead and make the required changes – which he did. (I was sent the amended and sealed Transparency Order – after chasing it – on 7th June 2024).

The judge took the opportunity to reinforce the point that Transparency Orders should be properly considered by those who represent the parties. “I understand how precedents are just used and reused, but it’s an important matter and it needs to be right for each individual case and not just boiler-plated out”.

He also referred (as he had two days earlier) to my concern about the Transparency Order as having provided a “learning experience” – and said, helpfully, that it’s “not a blame exercise – I’m just trying to get it right first time around”.

The substantive matter of the hearing was dealt with very quickly. It concerned whether or not P has capacity to make her own decisions about where she lives. It seems that where she lives now is so unsuitable, and causes her so much distress, that there’s reason to doubt that she has that capacity – but in a better environment it’s possible that she would regain it. Her current placement has served notice of termination on her, so it’s urgent to find somewhere else for her to live. At the next hearing (probably 17th or 18th June 2024) the issue of capacity will be considered again: “I’m not passing over the capacity issue, but a roof over this lady’s head is absolutely paramount.”

I’m very pleased with the way this judge deals with what are pretty clearly simply technical errors in Transparency Orders. These errors are, unfortunately, pervasive.

DJ Eaton-Hart’s practice compares very favourably with that of judges who ask for submissions, wait for counsel to take instruction, delay consideration until future hearings, or even require us to submit a formal application to vary the Order via a COP 9, resulting on a couple of occasions in pointless, expensive and time-consuming hearings devoted solely to fixing a technical error.

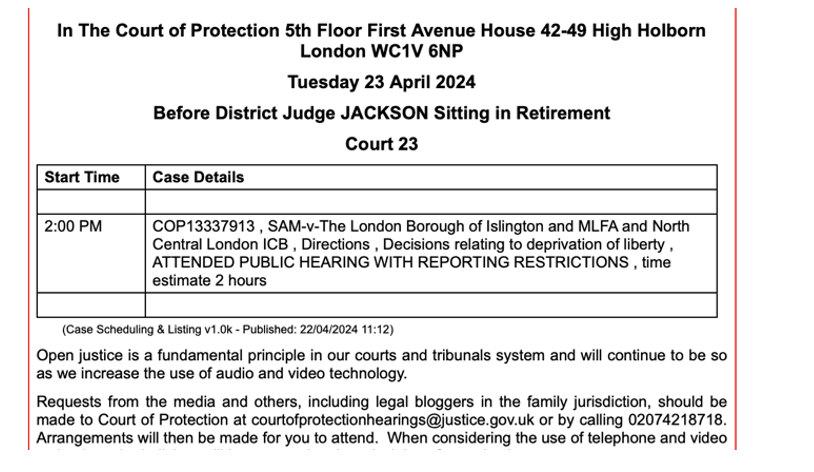

Transparency Order No 3 from DJ Smith: Received 20th May 2024

At both hearings I’ve watched before DJ Eaton-Hart, the Transparency Orders that needed fixing were made by DJ Smith. So, when I saw a hearing listed before DJ Smith, I immediately asked for the link.

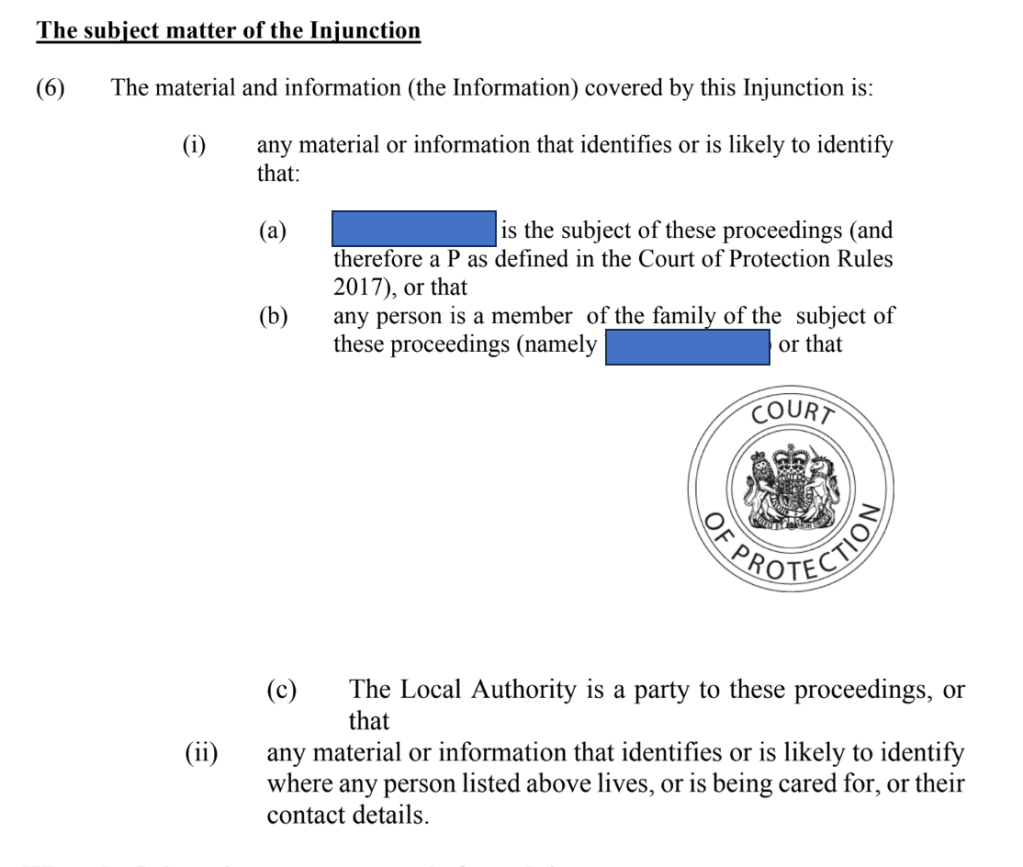

As it happened, the hearing was vacated, but not before I’d been sent the Transparency Order – and, yes, it was made by DJ Smith, and yes, like the other two Transparency Orders I’ve seen from DJ Smith, it prohibits identification of a public body. Actually, two public bodies: the local authority (§6(i)(c)) and the Official Solicitor (§6(i)(d)). Here’s the relevant part of the approved and sealed Transparency Order as I was initially sent it for this case (COP 14100128).

I was alarmed by the recurrent pattern of technical errors in Transparency Orders from this judge, and especially concerned that, on this occasion, the Transparency Order also prohibits us from naming the Official Solicitor. Increasingly we are seeing recently-made Orders prohibiting us from naming not just local authorities, Trusts and ICBs but also the Public Guardian and/or the Official Solicitor (see, for example, my blog post: “Challenging a Transparency Order prohibiting identification of the Public Guardian as a party”). So, I wrote to both Mrs Justice Theis (Vice President of the Court of Protection) and Senior Judge Hilder – and also raised my concern at a COP User Group Meeting. (I think it is those actions on my part which led to a memo being sent out to the judiciary informing them that they shouldn’t be routinely anonymising public bodies.). And at the COP User Group Meeting, HHJ Hilder advised me to complete COP 9 applications to get these erroneous Transparency Orders amended.

So, that’s what I did next.

Here’s the relevant part of my COP 9 formal application to vary this Transparency Order.

I also wrote to the Official Solicitor:

The response from the Official Solicitor was interesting: “Please be advised we were not aware of the order referred to and we have checked our records and as far as we can see the Official Solicitor has had no involvement in these proceedings and we are therefore not in a position to assist”.

I remain baffled as to why DJ Smith made an Order that the Official Solicitor could not be identified as having taken part in the proceedings – which it seems she didn’t – or even as having been referred to in the proceedings.

Within six hours of submitting my COP 9, I received an amended (sealed) Transparency Order approved by DJ Smith as below. The local authority and the Official Solicitor have been removed. I can now name them. (The local authority was Plymouth City Council). But there was no explanation as to why they were ever included in “the subject matter of the Injunction” in the first place.

Here’s the amended Order – in the form it should have been in first time around.

Transparency Order No 4 from DJ Smith: Received 22nd May 2024

On 20th May 2024 I spotted two hearings, both listed for 10am, before DJ Smith sitting in Plymouth, and asked to observe both.

I received an email saying that one had been vacated, but attaching a Transparency Order for the other (COP 14186566). As it turned out, that one was also vacated, but I was delighted to note that the Transparency Order was (almost) correct. The judge had (almost) got it right first time around!

The remaining error (not visible above) was in the file name – which looked to be P’s surname. This is a frequent error and breach of P’s privacy in many of the Transparency Orders we are sent.

I also noted that the Transparency Order was freshly minted: it had been made just two days earlier, on 20thMay 2024.

Final reflections

So, the effect of all this intervention on my part seems to have been that DJ Smith will not in future be making Transparency Orders that routinely anonymise public bodies, and will (I presume) be amending those she has already made. I eagerly await the next opportunity to check one of DJ Smith’s Transparency Orders and hopefully to observe a hearing before her.

Transparency Orders are not new. They were introduced with the Transparency Pilot in 2016 and the “standard” template has remained virtually unchanged ever since. The 2017 version is publicly available as a downloadable pdf.

The part of the Order I’ve focussed on in this blog post is the paragraph called “The subject matter of the Injunction” and here’s how it looks in the template.

The problem seems to be that it permits (at 6(i) (c)) an anonymised reference to “any other party” – and this is being interpreted by some lawyers and judges as permitting the court routinely to prohibit identification of parties such as local authorities or even the Office of the Public Guardian or (oddly) the Official Solicitor.

This does not seem ever to have been intended. In February 2016, the Court of Protection Handbook published a guide to the “Transparency Order in Plain English” which stated explicitly that “Normally you will be allowed to name the local authority, CCG or NHS Trust who is involved in the case”. The exception to this normal practice is (rarely) when naming the public body risks identifying the protected party.

I’m not sure how it’s come about that some judges seem routinely to be anonymising public bodies. What is clear is that nobody has been challenging the practice.

Until very recently, it was common for observers not to be sent Transparency Orders and around half of our blog were posted without sight of them.

Since the beginning of 2024, that’s changed dramatically – possibly as a consequence of evidence I submitted to the court, to the working group of the COP Rules Committee focusing on Transparency Orders, and to the Ministry of Justice (see: “Anxious scrutiny or boilerplate? Evidence on Transparency Orders”). We do now almost always receive Transparency Orders – and so of course that mean we can see the errors in them. And observers are increasingly challenging those errors, and taking up court time in doing so.

The problem for us, and for the court, is that all these challenges are very labour-intensive and costly to the public purse. I accept that the court is committed to the principle of open justice, and that these are administrative and technical errors rather than deliberate attempts to prevent us from reporting on matters of public concern. Not all members of the public agree with me on that – for some observers, these errors are clearly creating a negative impression of the court’s commitment to transparency. But whether they are cock-up or conspiracy, they have the same effect of breaching our Article 10 rights for no good reason.

There must be a better way of providing lawyers (who draft the Transparency Orders) and judges (who approve them) with the “learning experience” they need so that Transparency Orders are right first time around.

Postscript, 11th June 2024

A few days after publishing this post I spotted another hearing before DJ Smith in Plymouth, listed for at 10am on 11th June 2024 (COP 1412356501). Unfortunately it was listed as “PRIVATE”. I checked with court staff that it really was private and was told it was.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 500 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and tweets @KitzingerCelia

[1] Dates of TOs by DJ Smith: COP 14203764 made on 31st January 2024; COP 1424179T made on 24th April 2024; COP 14100128 made on 20th June 2023; COP 14186566 made on 20th May 2024.