By Amanda Hill, 9th May 2024

The protected party in this case (“L”) is a man in his twenties with “significant learning disability”, autism and complex physical disabilities. He had been living at home with a care package in place until July 2021, when his care package broke down and he was moved to a new placement after an application by the Health Board to the Court of Protection. This was supposed to be a temporary emergency placement, but L is still there nearly three years later because, over the years, suitable alternative arrangements have not been found

Now a placement needs to be found urgently. Following a long period of notice, his current placement is threatening to withdraw care if he does not leave immediately. The problem is that the only options before the court are either a sub-optimal placement an hour and a half away from the community and family he loves, or hospital admission, which nobody seems to accept would be in his best interests.

Background to the hearing

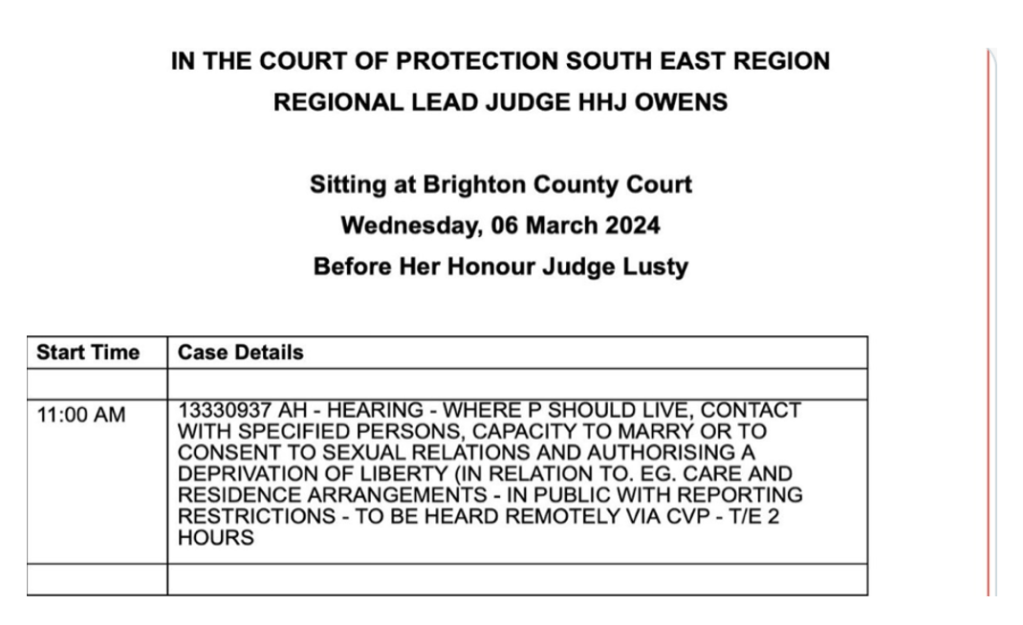

This hearing, listed for three hours on 19 April 2024, was the latest in a long running case (COP 13290314) before HHJ Porter-Bryant[1], sitting in Newport, Wales. Celia Kitzinger has blogged about one aspect of the case from an earlier hearing here. There are also two judgments, from December 2023 here, and an appeal upholding that judgment (CL v Swansea Bay University Health Board & Ors), published a few days before this hearing.

As noted in the earlier blog post, this is “a very complex and long-running case – and one that is causing immense distress to the mother”. Over time, the relationship between L’s mother ‘C’ and various professionals has broken down, to such an extent that she is prevented from visiting L at his placement. Various allegations have been made about C’s behaviour and C was discharged as Personal Welfare Deputy for L. In order to move things forward, protocols to do with medical clinical appointments, contact in the community, and care planning have been agreed between C and the Health Board. The initial objective of this hearing was to consider those protocols, as well as to consider the long-term residence, care and contact options for L, but, as the judge said[2] in oral judgment at the end of this hearing, matters have taken a turn and the situation has moved on rapidly.

Things have reached a crisis point.

The placement – having given L notice to leave in September 2023 – has now enforced the notice. The staff are at the “end of their tether” with the notice period and it is now “D Day”. They’ve said “enough is enough” and they will care for L no longer. The placement manager is off work with stress and there is a threat of union involvement and action. There are fears that the staff would even walk out “and that fear seems to be justified” according to the judge.

Two options have been found by the Health Board: H, a private supported living placement that has a vacancy for L, or hospital.

Rosie Scott , counsel for the applicant Health Board, set out the matters before the court:

1) Is it in L’s best interest to reside at H, or another placement?

2) C’s contact with her son

3) Care planning protocol

In the event, there was no time to discuss the care planning protocol and most of the time was devoted to the first issue of residence.

Residence options for L

There was only one available community option offered by the Health Board, “in the sense both that there is a vacancy and that the Health Board has determined that it will commission a place there”.

The Health Board had considered other community options before coming to its commissioning decision. One was another supported living placement, which was ruled out because it would result in “overprovision” for L: 2 to 1 support 24 hours a day (he’s assessed as needing only 12 hours a day) and ‘non-negotiable’ clinical support from people like an Occupational Therapist. During the hearing, Counsel for the Health Board conceded that cost was a factor, but said that L’s autonomy weighed more in the commissioning decision. Domiciliary care options (proposed by his mother) were also considered but ruled out.

The only alternative to this community option was a “bed within the acute admission unit” of a local hospital. This would mean a much more restrictive environment – and L does not need treatment.

Despite the stark alternatives, there were concerns about the proposed placement – including the space available and particularly whether there is a fire risk for L, due to the size of his wheelchair. Other issues include the compatibility of L and the other residents, and the fact that the placement is an hour and a half away from L’s home town, where he has lived all his life.

There has been a high level exploration with L about moving to H. When shown photos of H, he reacted positively to some of them but he didn’t like the photos of the bedroom. He wants to stay where he is (which isn’t an option) and wants to see his mum and dad more, which would be difficult with a placement so far away.

In his summing up the judge said “Community is of magnetic importance to L, he is a (home town) boy”, echoing submissions by Counsel for the father of the “magnetic importance of family” for L and “being where he is familiar”. It is also an issue for L’s parents, as it would make contact with L more difficult.

Counsel for the Health Board stated, however, that the placement is suitable, available and can meet L’s needs. She acknowledged that a closer placement would be ideal but stated that the search for a placement had been a national search and they were “lucky” that it was (only) an hour and a half away. She argued that it was in L’s best interests to move there. It is the only option in the community and they would be asking the court to authorise L’s deprivation of liberty at this placement. She proposed a 6-week review and raised the prospect that it could become more than an emergency placement; it could be a long term placement for L. The “bottom line” or ‘stark fact” is that no other options (in the community) are being considered by the Health Board. This was partly due to questions about L’s needs but also due to financial constraints. L’s Litigation Friend (represented by Nia Gowman) does not, in contrast, see H as a long-term option, but agrees with the Health Board that it is the only option for now.

The alternative to H before the court is hospital. But there was discussion about how viable an option for L this really is. Neither counsel for L or for his mother considered it an option. Even the Health Board proposing it did not seem to think that it was an appropriate option, unless a community option was not available. Rosie Scott stated “I suspect it is not necessary to say that a clinical environment in hospital is not suitable for L” if a community option is available. She continued that it would take a long time to find somewhere else and it would not be quicker if L is in hospital. She emphasised that “going to hospital does not mean another option will become available”. In other words, if L was placed in a hospital, he could be there for some time.[3] Counsel for L did not consider hospital to be a viable option and was surprised that the Health Board was even considering it. With a hospital admission there was no concept as to how L would be cared for.

At some point during the discussions, the judge made a comment (which I didn’t catch) which implied that hospital had only been put forward as an option by the Health Board in order to cast the community option in a better light. Rosie Scott took umbrage at that. She stated that she “must push back on the idea that hospital is being put forward as a black art to shine light on [the community option]” and the judge accepted that it was an “unwise comment on my part”. He referred to this again in his oral judgment, stating “I had suggested disingenuously that a cynic would say that the [community placement] was presented as an alternative to hospital to make it more attractive but I was not suggesting that it was inappropriate. It is what it is, there are only two options”. He continued by saying that little is known about the ward apart from it is in hospital in [home town], little is known about whether L would have his own ward, or contact, or community access…. “it is a hospital setting and not a home. It is a setting for those with difficulties different to L’s, it is a medical environment……..it is however close to home…….Much of the evidence for a placement is not before the court because the Health Board do not consider it a viable option. I agree”. He stated that it is hard to see that it would be in L’s best interests.

Not surprisingly under the circumstances, the judge decided that it was in L’s best interests to move to the community placement. The current predicament was that in his current placement staff could walk out on L, he could be evicted, which could lead to him going to hospital. Therefore, it was in his best interests to move to H on a short-term basis, whilst accepting that there were still concerns. In particular, a fire evacuation plan should be prepared before L moved there.

Everyone seemed to hope that the new placement would provide the opportunity for a “fresh start” and, despite all the problems relating to contact in the current placement, the Health Board was not seeking contact restrictions: “At present there are no restrictions sought by either the Health Board or the owners of [community placement] in terms of [the mother’s] presence at [community placement] or in contacting staff. It is hoped that none will be necessary in this fresh start”.

The judge acknowledged that the start of the relationship had been positive. Imposing restrictions could have the opposite effect (to that intended) to the extent that the relationship would start on a “poisoned basis”. He stated that it was a difficult balancing exercise such that if he got it wrong, “we could go back to the beginning” and be in a worse position. “I stress to the court that the placement needs to work. If it is put to me that the relationship is deteriorating, I will put measures in place to ensure that the placement is retained”.

The judgment concluded with the judge stating that the search for a long-term residence should continue. For example, domiciliary care could be met if the Health Board could fund it, or another suitable placement. However, he said that he didn’t wish to make that a requirement for the Health Board, “I appreciate the significant resources that have been given over to this case already. We aren’t there yet”. He acknowledged there may be further developments. Could the drawbacks of this placement be mitigated? If L becomes happy at the placement, that would be a significant factor.

Finally, there was a brief discussion about C allegedly breaching the Transparency Order. She had sent an email in mid-April to her member of the Senedd, apparently wanting their involvement as she was not happy with the Health Board’s commissioning decisions. The Health Board alleged that this breached the Transparency Order because it “identified that C is the mother of a P involved in Court of Protection proceedings to somebody who is not involved in proceedings or involved in L’s care or support”.The judge stated that he realised C wanted help (from her Senedd member): “C, I know you reached out for help, but those orders are there for a reason, you can get yourself into trouble. I’m aware why you did it”.

The hearing concluded with another hearing set for July, to consider how the placement is working and the protocols that were initially due to be covered in this hearing.

Reflections

A shadow hanging heavily over this hearing was the fact that hospital was being considered an option even though that would be a clinical environment and not suitable for his needs. It seemed to be posited as a residence of last resort for L – but still a possibility if there was no community placement for him. The paucity of options is an extremely sad state of affairs.

As the judge stated in his December judgement, he recognises that C feels very strongly about trying to ensure that L obtains the right care: “I have never lost sight of her love or strength of feeling and determination to do all that she can to secure what she feels is the best outcome for P”. She has had her personal welfare deputyship taken away, even though there were no findings of wrongdoing. She wants her assembly member to help her challenge the Health Board’s commissioning decisions but is unable to contact them due to the transparency order in place. And now her son is being moved an hour and a half away from her to a placement that she doesn’t feel is approriate, but is the only viable option. And a sword of Damocles is hanging over her: in effect, “don’t rock the boat or you won’t be able to see your son”.

I should say that L’s father was also represented in this hearing, and the dynamics of the relationship between him and C are also a factor in decisions about contact. I feel that it can be very difficult for families, who have to tread a fine line if they feel their loved one is not receiving the approriate care. At the same time I know that professionals are placed in difficult situations too. That said, if a placement can turn around and say they won’t care for somebody anymore, then the odds are certainly stacked. It’s a very difficult situation to navigate.

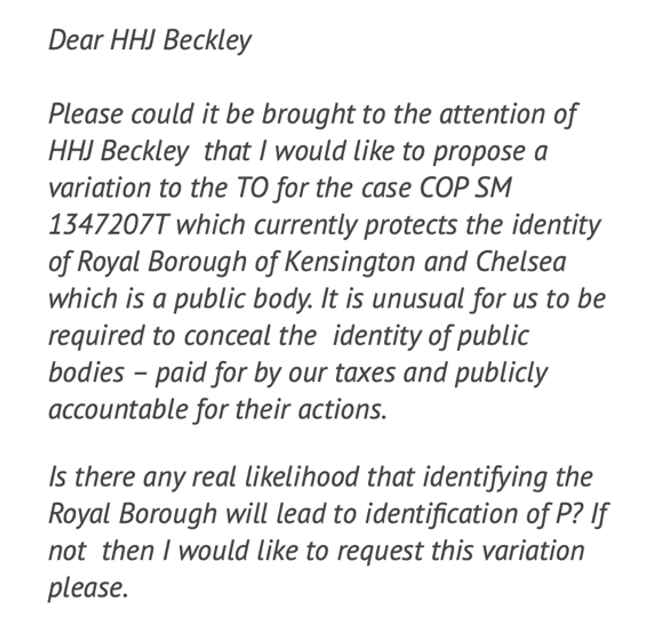

Finally, the discussion at the end of the hearing about the Transparency Order highlights, in my opinion, the practical difficulties faced by families whose freedom of speech is restricted by a Transparency Order, and whether the restrictions are really proportionate and necessary. I understand why restrictions are in place, to protect P, but I do wonder if there is not some balance to be struck as the restrictions are very onerous for families practically. These orders are generally in place until the court orders otherwise and, rying to get a Transparency Order varied (changed) can be extremely difficult.

Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is on X as @AmandaAPHill

[1] I am grateful to the clerk at Newport court who facilitated access and tried to help when I encountered sound issues, which was frequently. I was the only observer on the link and this was a fully in-person hearing. Thank you too to Rosie Scott and Nia Gowman for sharing their very helpful position statements.

[2] It is forbidden to record any part of a hearing and I don’t touch type so my notes will not be 100% accurate.

[3] People in the United Kingdom with learning disabilities can end up staying in hospitals for a very long time. This is a recent report from BBC Scotland: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ck5k91j6g00o?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR32TFS2o5y3TuHB-WSWTcLbYhxr6JkDcv4qQJbjqqmRDdglltMdmFJ88Ag_aem_AboDYaAZGAMIfFosrnwD0YwJhlpfUM4gX2YT_Q01QtZ2Su91fxtncBEvlu53aCgU5_frI5bRMLcvLhDcwwCOXI-N

And it is an issue in Wales too: