By Claire Martin, 11th July 2023

One of the most draconian decisions the Court of Protection can make is to restrict contact between people who love each other and want to be together. That was the issue in this hearing.

The Health Board was seeking urgent court authorisation for an extension to an order restricting contact between the protected party at the centre of this case (Laura Wareham[1]) and her parents. In fact, they wished to stop all contact (face-to-face, telephone, FaceTime) for a period of twelve weeks, to ‘aid Laura’s mental health recovery and allow her to be discharged from hospital as soon as possible’ (from Position Statement kindly shared by Emma Sutton, counsel for the Health Board). They also proposed to vet all letters between Laura and her parents.

As Laura and her parents made clear, they saw this as violation of their human rights – most especially Article 8, respect for their private and family life.

On the basis of this, and similar, cases it’s clear that, in some future scenario if one of my daughters were to lose capacity to make her own decisions about contact with me, that the Court of Protection could, in theory, declare that I am harmful to her and prevent me from seeing her. That possibility fills me with dread. It’s important for us all to understand how this can happen.

Contact restrictions

The court can restrict contact between the protected party (P) and someone else when P lacks capacity to make their own decisions about that contact and the court decides that having contact with them is not in P’s best interests – even if they desperately want it.

When someone is admitted to a care home, the effect may often be to restrict that person’s contact with family members. This was an issue for many people during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when people could not travel to see loved ones, and visiting was either banned altogether or severely restricted to video-calls, ‘window contact’, or short meetings in gardens. The ‘right to family life’ (Article 8 of the Human Rights Act) was one of the most painful casualties of the public health emergency and was contested in court (e.g. “Right to family life in a care home during a pandemic”). The care home a person moves to is sometimes some distance away from the family home, and this too can make visiting difficult (see, for example, “What God has put together, let no man put asunder”).

But sometimes reduced contact is not a ‘side-effect’ but a deliberate court-ordered strategy because contact is declared not in the person’s best interests.

For example, in one case the court made a final order that there would be no contact at all between P and a man whose companionship she craved – on the grounds that he was exercising coercion and control over her and manipulating her with the intention of securing financial benefits (specifically a ‘predatory marriage’).

More often, contact is restricted, rather than banned altogether, in the vulnerable person’s best interests. For example, the judge ordered that a wife who was said to be abusive, coercive and controlling of her husband (who has dementia and Parkinson’s) was to have contact with him only by letter or by phone, and that face-to-face contact would be possible only with the prior agreement of the local authority (“Abusive” wife agrees to move out of “the matrimonial home” with continuing (albeit restricted) contact with P: An agreed order). Similarly, contact between Mrs M (who has dementia) and her son was restricted to supervised contact only, i.e. they can only see each other if a member of staff is present to observe them. This was ruled to be in Mrs M’s best interests because the judge found that the son was opposed to Mrs M taking her prescribed medication and was persuading her not to do so, and was also “exhibiting challenging behaviours with professionals” which “upset his mum” (see “Conditions on contact between mother and son”).

Applications for restrictions on contact often relate to family members alleged to have been abusive to care staff and professionals, and to have challenged the treatments or care plans in place for their relative. As one blogger, who found when she read her own sister’s medical records that she had been characterised as “difficult”, “vociferous” and “obsessed with the Mental Capacity Act” (!) wrote: “”family members who have views about a person’s treatment which strongly differ from those of healthcare professionals may sometimes be framed as unreasonable, aggressive or not having their relative’s best interests at heart”. Sometimes, as in the case she observed and blogged, the outcome of the hearing is that the judge entirely exonerates them and declines to restrict contact.

But contact restrictions are a more common outcome – and of course it can feel to families as though they are being punished for seeking better treatment for their loved one, and that fundamental human rights to family life are being violated.

We’ve blogged several such cases, e.g. a case where a judge ordered that a man could continue to visit his son but that the visit would be ended immediately if he were abusive to staff (here) and a case where a man who was coercive and controlling was prohibited from having direct face-to-face contact with his wife (here).

In another case (one I watched and blogged about myself), a mother was banned from seeing her daughter, who desperately wanted to come home, because she was a bad influence on her daughter and (the court said) was encouraging her to refuse her medication. (See Medical treatment, undue influence and delayed puberty: A baffling case).

It’s clear from these court decisions that Article 8, which protects your right to respect for your private life, your family life, your home and your correspondence is “qualified” – i.e. the state can interfere with these rights to protect the rights of another person, or the wider public interest. And that’s what happened in this case.

The hearing

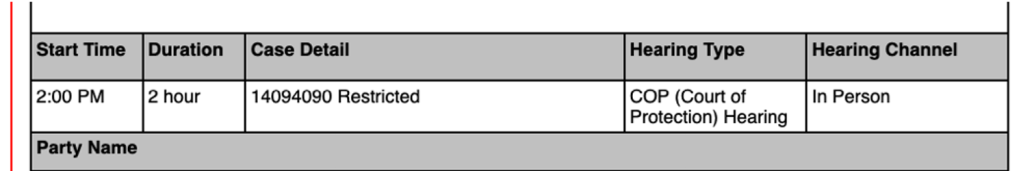

It was an urgent application made by the Health Board, heard (via MS Teams) on Monday 12th June 2023, before Mr Justice Francis (COP 1397774T). When I joined, there were thirteen people on the link waiting for the hearing to begin.

The court clerk, at just gone 2 o’clock, said ‘Is everyone here?’ Laura (the protected party) replied ‘I’m here despite best efforts to the contrary’[2]. Her voice was strong and confident. I had read all of the earlier blogs and newspaper articles about Laura’s case[3], and seen her television interview, so I knew that she was very able to speak up for herself. Her mother called out ‘Love you Laura’. Laura replied: ‘Love you mum’.

I knew that it was entirely possible that Laura hadn’t had in-person contact (or had had minimal contact) with her parents prior to this hearing, because Celia Kitzinger’s blog, in February this year, reported that an outstanding issue was ‘whether and how face-to-face contact between Laura and her parents can happen, given that in-person visiting arrangements have been suspended at the request of the Health Board due to her mother’s behaviour towards health care staff’.

So, I was aware that the rest of us on the link might have been witnessing the first time that Laura and her parents had seen or spoken to each other for some time. That felt uncomfortable.

I imagine most of us, the general public, would think that it would never happen that we would be prevented by the state from freely seeing the people we love, who sustain us and who we want to see. I was very interested to observe how the court would deal with this.

Background

Laura Wareham has been in hospital since April 2022. An earlier blog provides this summary:

“A woman in her 30s [who] has “a hugely complicated medical background”, including a rare inherited disease, and a diagnosis of “autistic spectrum disorder”. According to Emma Sutton, who represents the applicant Health Board (Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board), she has “at least 19 different physical conditions”. The mother said there were far more. In addition to intubation and ventilation, she is receiving treatment for an acute kidney injury and sepsis.”

There have been several hearings for Laura in this contentious case. There is significant dispute between Laura and her parents on the one hand, and the Health Board and social care services on the other. Both the Health Board responsible for Laura’s care and Laura’s father, Conrad Wareham, have been the subject of judicial criticism (by different judges at different times) as reported in September 2022:

“Mr Justice Francis [the judge at the hearing I observed] made no criticism of specialists or the board, but said Dr and Mrs Wareham had been “interfering” with Miss Wareham’s treatment in a way that was “detrimental”.

He said the medical team treating Miss Wareham, who comes from Sheffield and is being cared for at a specialist unit run by the board, was entitled to treat her in the way it thought she should be treated.

Another judge had earlier criticised the board [Betsi Cadwaladr Health Board] after considering a different case, involving a man in his 40s, at another Court of Protection hearing.

Mr Justice Hayden said the man’s needs had been “substantially unaddressed”, “unacknowledged”, “unidentified” and “neglected”.

He said “so much” had gone wrong” and spoke of “substantial and alarming failures”.

P’s voice: ‘I am not being heard’

Judge: Can you hear us?

Laura: I can hear. I am not being heard, that’s the difference.

Judge: Good, that’s a good start.

Laura: Well, that remains to be seen.

This hearing was peppered with exchanges like this between Laura and the judge. Laura was not happy to have been found to lack capacity to speak for herself and did not accept that she needed a litigation friend (in the form of the legal team provided by the Official Solicitor). ‘It would be much simpler if I could just speak for myself’ she said.

Because Laura has been found to lack capacity to litigate this case, she is represented by the Official Solicitor, which means her ‘best interests’ (as the Official Solicitor sees them) are represented – but Laura herself is not represented in the way that legal teams usually represent their clients (see “Litigation friends or foes: Representation of P before the Court of Protection”). Any of us could be in this situation – if a judge deems us not to have capacity to conduct litigation. Then it is down to someone else to argue what they see as our best interests – which might or might not align with our own views. That’s quite a scary prospect to me.

And it presents the court with a tricky situation when P is in court, and when they can and do speak up for themselves and when their own view is different from that of “their” lawyer. It was clear that Laura very much wanted to be heard in her own right.

I have observed several hearings when P was in court. At this hearing I observed, with a woman who had ‘cognitive impairment’, the judge made a lot of time for her voice to be heard, even thought she had legal representation. That was not the case at this hearing.

Several times, Francis J said ‘We need to do it in turn, you will be heard I promise you.’ Adding at times, ‘I can mute the sound but I don’t want to do that’. However, Laura didn’t really get ‘a turn’.

On a couple of occasions, when the judge let her speak, the focus quickly diverted to someone else, like in this exchange:

Laura: I have had my hand up [Laura’s ‘digital’ hand was up throughout the hearing] …. Nothing about me without me.

Judge: I will give you your turn in a moment. ….

[Judge finished talking to counsel]

Judge: [to Laura] I can see you want to speak – don’t forget you are represented…

Laura: No, I am not. So far, it’s a breach of my human rights.

Judge: Which?

Laura: Freedom of expression, and religious belief, psychological torture.

Judge: Which religious right?

Laura: Freedom to pray with chosen people.

Judge: Let me go back to Mr Fernando

The ‘turn’ did not return to Laura.

I had wondered whether it might have been helpful, at the start, for Laura to know when she would be invited to speak in proceedings. I kept wondering when it would be her ‘turn’, and feeling anxious that her turn seemed to be like jam tomorrow.

Laura is autistic and it might have been reasonable to operate on the basis that some predictability could be helpful for her. At the same time, I could see that Laura wanted to speak at all times (with her virtual hand up throughout the hearing) – though this could have been because she didn’t know when she would be allowed to speak.

Why is contact between Laura and her parents being restricted?

The reason for this application, says the Health Board (represented by Emma Sutton), is because contact with her parents causes Laura to become very distressed and violent (for example, damaging property at the hospital, such as punching holes in walls, or staff ending up with their glasses broken). Following telephone contact with her mother recently, Laura had been detained under the Mental Health Act, and moved to a psychiatric ward for a period of time.

The Health Board also reports that Erica Wareham (Laura’s mother) has been ‘verbally abusive to a treating nurse’, though I don’t know the details of that allegation.

Laura (represented, via the Official Solicitor, by Grainne Mellon) and her parents (represented by Pravin Fernando) vociferously oppose this application, and, as I will report, contend that the Health Board and hospital staff’s allegations are ‘factually inaccurate’ and that ‘correlation is not causation’.

There are likely to be many issues of which I am unaware in this complex case, on all sides. I have had the benefit of being able to read the Health Board’s and Laura’s parents’ Position Statements prior to writing this blog, and would have liked to have read the Position Statement for Laura. I requested it from Laura’s counsel, but have not received it. This might mean that this blog is biased or misses important information, and I will do my best to reflect the hearing accurately, as well as reflect upon my own responses to that hearing, from my perspective as an observer, parent and NHS worker.

The Health Board’s position was supported by an independent expert psychiatrist (Dr Camden Smith), who assessed that Laura’s parents ‘contribute to her help-seeking behaviour’ and that, ‘on a balance of probabilities, Laura’s parents’ behaviour has a negative impact on her’.

Laura’s parents’ position statement states that Dr Camden-Smith only met Laura on one occasion. They challenge the conclusions reached as ‘reductive’ and note that Dr Camden-Smith was not going to be present at the hearing to have her conclusions scrutinised by the court. Moreover, they have not seen Laura in-person since November 2022, and have had no contact at all since 7th May 2023.

However, the Health Board was, Emma Sutton said: “… asking for a pause in terms of face-to-face contact. The Health Board is aware that there needs to be a careful approach. There needs to be some outside help – Dr Camden-Smith is an expert in autism and mental health and can give us a toolbox. We need to instruct an expert to help move this forward”.

My understanding, from that piece of information, is that the Health Board was suggesting that (after Laura has already spent 14 months as an inpatient) there is a need for an independent expert in autism and mental health to assist the hospital with how they care for Laura. And that this assessment needs to be conducted in the absence of any contact or involvement from Laura’s parents. I wasn’t sure what was proposed to happen with Laura’s care during the no-contact period that would ‘move this forward’ as the details weren’t discussed.

I don’t know all of the contentions made about Laura’s parents’ behaviour (or the details of the ones mentioned in the hearing) and cannot know whether what the Health Board says, or what Laura’s parents say, is accurate.

However, what I could see in the hearing is that Laura herself wants contact with her parents, and appears very distressed that she does not have this contact. Given that distressing Laura is what the Health Board says it is trying to avoid, I felt dubious about the likely success of an expert engaging Laura under these conditions.

Laura’s counsel, Grainne Mellon said ‘we want to agree a less restrictive form of contact – no more than four to five weeks.’ She mentioned needing to see a ‘clinical plan’, and Pravin Fernando said:

“The application is for 12 weeks [and] was said to be required for a period of reablement. The Health Board provides no rationale or plan as to what that would look like. You are being invited to restrict contact entirely without a plan – we don’t know anything.”

It wasn’t clear, at all, what the treatment plan was from the Health Board that necessitated the total absence of Laura’s parents from her life in order to be successful (i.e. to end up with discharge). It seemed as though there might be two reasons for the Health Board’s request: the parents’ behaviour towards staff at the hospital (described as, at times, ‘abusive’) and, more directly, potential ‘harm’ to Laura, as suggested by the expert witness in the form of ‘contributing to [Laura’s] help-seeking behaviour’ and the judge as ‘… to put it bluntly, her mother is winding her up’.

As I said, I don’t know the details of incidents presented as evidence of harm, either to the health care staff or to Laura. The Health Board, expert witness and judge were all observing a link between contact with her parents and Laura’s distress being exacerbated. I assume evidence was provided in the bundle (which I could not see).

Reflections on ‘abuse’ of NHS staff

This is a situation where balancing of the costs and benefits of contact is required. This is the first hearing I have observed for this case. I am new to the situation, and know a lot less than the Warehams and the services involved.

I have worked in the NHS for 30 years though. The NHS Staff Survey in 2021 reported:

“14.3% of NHS staff have experienced at least one incident of physical violence from patients, service users, relatives or other members of the public in the last 12 months”.

Collins English Dictionary definition of abuse is “extremely rude and insulting things that people say when they are angry” and “cruel and violent treatment”. In relation to workplace abuse, the Royal College of Nursing says:

“The RCN supports the Health and Safety Executive’s definition of work-related violence as any incident in which a person is abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances relating to their work. This can include verbal abuse or threats as well as physical attacks (Health and Safety Executive 2021). The RCN acknowledges that in health and social care, the approach to tackling work-related violence is nuanced and that ways of reducing the risk of harm to staff may vary in different clinical environments and with different client groups.”

NHS organisations often have a ‘zero-tolerance’ policy in relation to abuse and violence. And of course, it is completely unacceptable to be subject to ‘abuse’ in your place of work.

I sometimes think that the definition of ‘abuse’ can be quite wide, however. If, for example, a patient or family member raises their voice or shouts because they are frustrated or upset with the service or member of staff, is this always ‘abuse’? Discounting physical assault and discriminatory verbal attack, the interpretation of a person’s behaviour as ‘abusive’ can, I think, be in the eye of the beholder, as well as (or instead of) an objectively observable fact.

I am not expressing a view one way or another about Laura’s mother’s behaviour. I do not know what she did. I don’t know how people responded to her. I am expressing a view as a person first, and as a long-serving NHS clinician second.

What I am suggesting is that responses to others’ behaviour can vastly differ. I have seen this myself, time and again, working in mental health services in the NHS. My own (sometimes inner) responses vary, depending upon what is going on for me that day or at that time in my life.

Sometimes people are upset. Sometimes that is because they are receiving a terrible service. Sometimes the service is fine but they are frantic with worry about someone that they love and the usual social niceties go out of the window. Sometimes, it is because they might anyway lack the emotional, social and communication skills to address what is upsetting them. Sometimes, health care staff bring their own ways of responding to challenging situations, which might or might not be helpful. It’s complex.

I have witnessed occasions where patients’ and relatives’ behaviour has tipped into verbal or physical threat – and witnessed times when the NHS ‘system’ or individual staff response to people could have been significantly better. Some NHS staff (especially ambulance staff) are at regular, high risk of assault, just because of the area that they work in. This report details the rise in violence towards NHS staff, especially during and since the pandemic.

Both things can be true – that abuse does happen to NHS staff, and that others’ behaviour is sometimes framed as ‘abuse’ when it is not, really.

The RCN’s acknowledgement of ‘nuance’ is helpful. Sometimes things are in that grey area. Sometimes I think staff can adopt what they think is ‘zero tolerance’ when more ‘nuance’ is called for. For example, I have seen entries in patients’ notes which have caused me some concern. One entry stating that X ‘raised their voice’and the health worker recorded that they told the patient ‘I am not here to be abused’. Context is important. What was the person raising their voice about? Could their distress/anger/raised voice be understood differently, other than as ‘abuse’? That particular example was the wife of a man living with dementia who (reading through all of her notes) seemed simply at the end of her tether.

I have been on the receiving end of people’s anger, frustration and distress. It’s never pleasant, but it is not always ‘abuse’. I am not talking about anything physical here – nor minimising the impact of verbal attack. I am saying that how we all communicate with one another is complex and nuanced. Often, just by virtue of being in receipt of healthcare, patients and relatives are subject to a power dynamic that already places them in a vulnerable position. Sometimes, it could be helpful to try to understand this relational complexity, and to see ourselves as part of the dialogical pattern that might contribute to their ‘behaviour’. It’s a difficult area, and I am in no way suggesting that discriminatory verbal or physical abuse should be tolerated or ignored.

I had a quick look at policies to protect staff from abuse in the NHS. This one, referencing zero-tolerance, says: “Staff should not be left upset and distressed following an interaction with a patient”. That feels like an impossible target to achieve. The same interaction could upset some people and not others. This aspiration also places the emphasis on how staff should have a right to feel, rather than an objective measure of acceptable and unacceptable actions from others. I think this target runs the risk of all staff thinking that they are entitled not to be upset! How can that be helpful for those areas of ‘nuance’?

Final Submissions and Judgment

There had been an adjournment in the hearing for counsel to confer to see if they could reach a compromise position. The judge also had two other hearings waiting and had been frank that this hearing had not been listed for long enough, and he had not been given sufficient reading time.

When I rejoined the link, I could see that Erica Wareham was crying and Laura was also crying and wiping her eyes. They were mouthing and gesturing to each other. It was quite difficult to witness and I was fully aware that they knew everyone could see them when they might be feeling very vulnerable, yet this was their only means of contact at the moment. Erica Wareham was also talking to her husband animatedly. Conrad Wareham was sitting back in his chair (and had been throughout the hearing) looking thoroughly fed up, whereas Erica Wareham was often leaning into the screen, and sometimes seemed to be shouting (though on mute).

The plan that the advocates had agreed, and asked the judge to order, was for half an hour contact per week between Laura and her parents, via MS Teams, on the basis that it would be recorded and transcribed. This was to ensure that communication remained, in the view of the Health Service, ‘appropriate’ – again a position firmly challenged by Laura’s parents.

“The court will recall that Dr and Mrs Wareham have not had any contact with Laura since 7 May 2023 so how does the Health Board attribute Laura’s ongoing fluctuating negative presentation to Dr and Mrs Wareham? The Health Board attributes too much responsibility to Dr and Mrs Wareham for Laura’s presentation, rather than consider that her personality and behaviour is a manifestation of her.” Laura’s parents’ Position Statement (kindly shared)

Certain topics were not to be discussed between family members. Emma Sutton proposed that ‘if Erica Wareham and Conrad Wareham start talking about the proceedings or if they do not redirect when medical issues or controversial issues are raised, the Teams call will be terminated’.

Contact would be increased to one hour per week, if all went as agreed.

Then counsel for the parents raised what must have been a difficult topic:

Counsel for Parents: There is one last issue to raise. I am instructed to request – to find an alternative Tier 3 judge to preside over this matter. I am in an invidious position. Some orders you have made and recitals you have made reflecting your opinion – they are of the view that you have taken a specific stance on their conduct and way of engaging that is likely to impact the way future decisions are made, particularly in the context of specific things from today like neurodiversity and Mrs Wareham’s autism. Their preference would be for another Tier 3 judge to look at this with fresh eyes.

Judge: Thank you for the tactful way you have done this. What is the timescale? Have we got a final hearing set down yet? [after discussion about court and judge availability] What I will say – effectively this is an invitation to recuse myself – I will do the next hearing and if you are going to make an application for me to recuse myself, set it out with the reasons. If the judge has lost the respect of parties, that’s one thing. On the other hand parties can’t just request a different judge when they want. I will hear it at the next hearing. A whole day, certainly half a day at least – effectively today your one hour has become half a day.

Laura: It may be a day for you but it’s over a year of my life that’s been stolen.

Pravin Fernando submitted that the Health Board’s treatment of Mrs Wareham was ‘indirect disability discrimination’ due to her autism. The judge noted:

“I am aware that Mrs Wareham … it has been said has her own things that need to be protected. I have talked about the Local Authority owing her a duty – the Wellbeing Wales Act – I have to pay extra attention to make sure that if Mrs Wareham is suffering from any condition that she is protected by [the court].”

In his judgment, Francis J said that he would ‘adopt the Trust’s position for the next few weeks’, i.e. no face-to-face contact between Laura and her parents. His reasoning was that, if in-person contact were to be allowed then the parents “inadvertently or intentionally, will wind Laura up and create a situation akin to the one before”. He authorised the MS Teams contact (to be recorded).

Francis J acknowledged that Laura’s own position was not that taken by the Official Solicitor, and that the reason the court was sitting was because Laura ‘lacked capacity to make her own decisions”. Laura and her mother were visibly upset and Laura continued to speak out: “I do not lack capacity. I will not be silenced – nothing about me without me – please stop telling people to mute me.”

The judge left the link.

Laura: ‘I love you mum and dad. (Crying) You don’t respect my human rights.’

Laura was still shouting out as the line was disconnected.

Draconian Decisions

Clearly, preventing family members from having contact with one another is a very serious decision to make and it’s hard to watch the distress it causes protected parties and their families in court. This hearing for Laura was an acute example of such an awful situation. That does not necessarily mean the decision is not justified.

I don’t have access to more detailed views of Laura. The phrase ‘correlation is not causation’ was said several times, both by Laura and by her mother. I took that to mean that they acknowledged that Laura might be upset after contact with her mother (at one point Laura said she’d had a ‘meltdown’) but that it wasn’t the case that the contact caused the distress, or that stopping contact would lead to improvements for Laura.

Pravin Fernando, counsel for the parents, cast doubt on even the correlation, describing what he thought was a ‘troubling’ lack of evidence from the Health Board that Laura’s behaviour had improved following no contact with her parents. Emma Sutton firmly disputed this and evidenced several citations in the bundle from the medical director of the hospital.

I was left with a sense of niggling anxiety after this hearing. I think that was about what seemed like a lack of an exit plan (perhaps that will come) and a family and system at absolute loggerheads. Observing Laura, I could see that she is very unlikely to join in with a care plan recommended by an expert in autism to ‘move things forward’, knowing full well that this care plan is predicated on the absence of contact with her parents. Especially, perhaps, a care plan based on that expert’s advice to remove Laura’s parents from the picture entirely (albeit for a period of time). There seems to be an impasse, that I wasn’t convinced would be resolved by adopting the Trust’s position for a few weeks. Maybe the interim judgment wasn’t designed for that. Pravin Fernando is considering an application to instruct (perhaps jointly) an independent expert, which could offer a way forward.

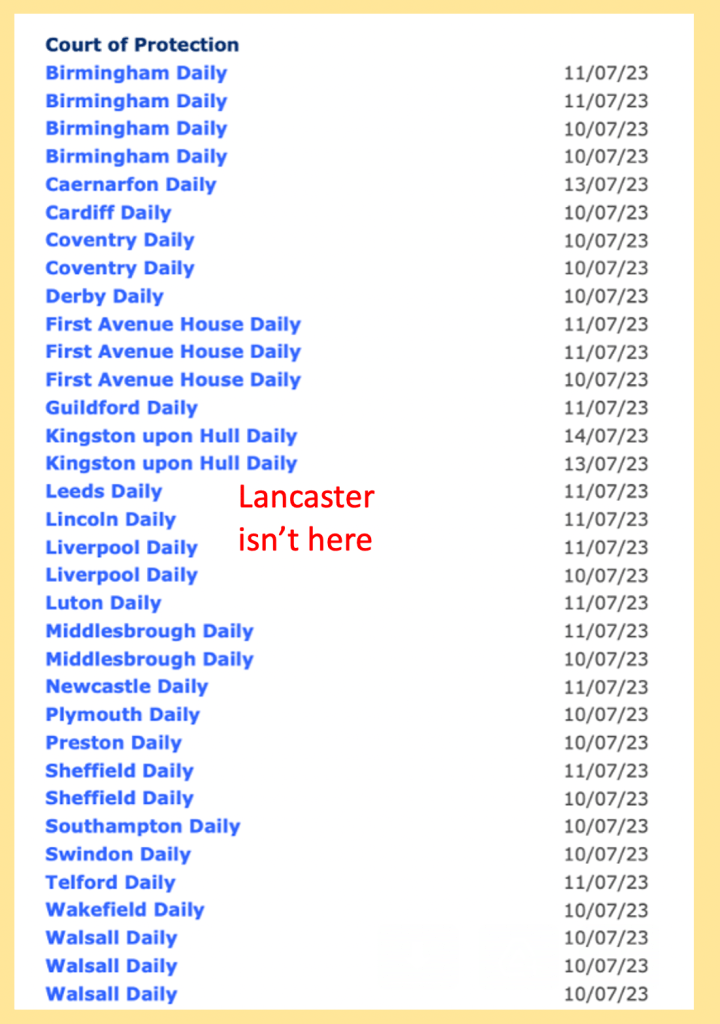

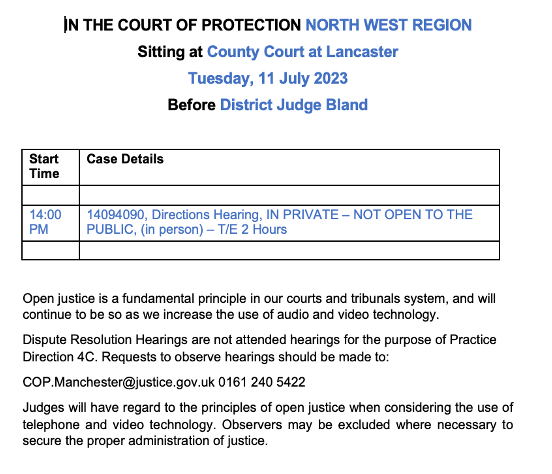

The next hearing (also before Francis J) is likely to be mid-July 2023.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core group of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published several blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She tweets @DocCMartin

[1] The Transparency Order permits us to name Laura Wareham (and her parents, Conrad Wareham and Erica Wareham) but not the hospital where she is being treated, or any of the professionals involved in her care.

[2] All quotations are based on contemporaneous notes and are as accurate as I can make them, given that we are not allowed to audio-record court hearings. They are unlikely to be 100% verbatim.

[3] ‘I am fearful for my daughter’s life: serious medical treatment in a contentious case’, ‘Stand-off about the appropriate expert: a pragmatic judicial solution’, ‘Judge criticises consultant concerned about how doctors are treating his daughter at Welsh Health Board’, ‘Retired nurse tells judge her daughter is not safe in Betsi Cadwaladr Health Board hospital’, ‘Rotherham woman with rare condition steps up life-changing surgery campaign’