Ruby Reed-Berendt and Bonnie Venter, 12 May 2023

To our knowledge, the Court of Protection has only once before grappled with the issue of capacity and organ donation in the context of learning disability: when it considered the case of William Verden last year. You can read the judgment in that earlier judgment here: Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust v Verden & Anor [2022] EWCOP 4. The Open Justice Court of Protection Project has published a selection of commentaries from observers who watched the William Verden hearings (e.g. here, here and here).

Following in the footsteps of the William Verden case, the individual at the centre of this case, who we will call Isaac (not his real name), is 28 years old and has a diagnosis of learning disability and “Autistic Spectrum Disorder”. He has end stage kidney failure and the key issues before the court concerned what treatment would be in his best interests. The usual options would be to provide renal replacement therapy via dialysis (where the role of the kidneys in cleaning blood is taken on externally) or transplant.

Isaac was receiving treatment at his local trust (Trust W), but the potential transplant would take place at a specialist team at another nearby hospital (Hospital X), which was part of Trust Y.

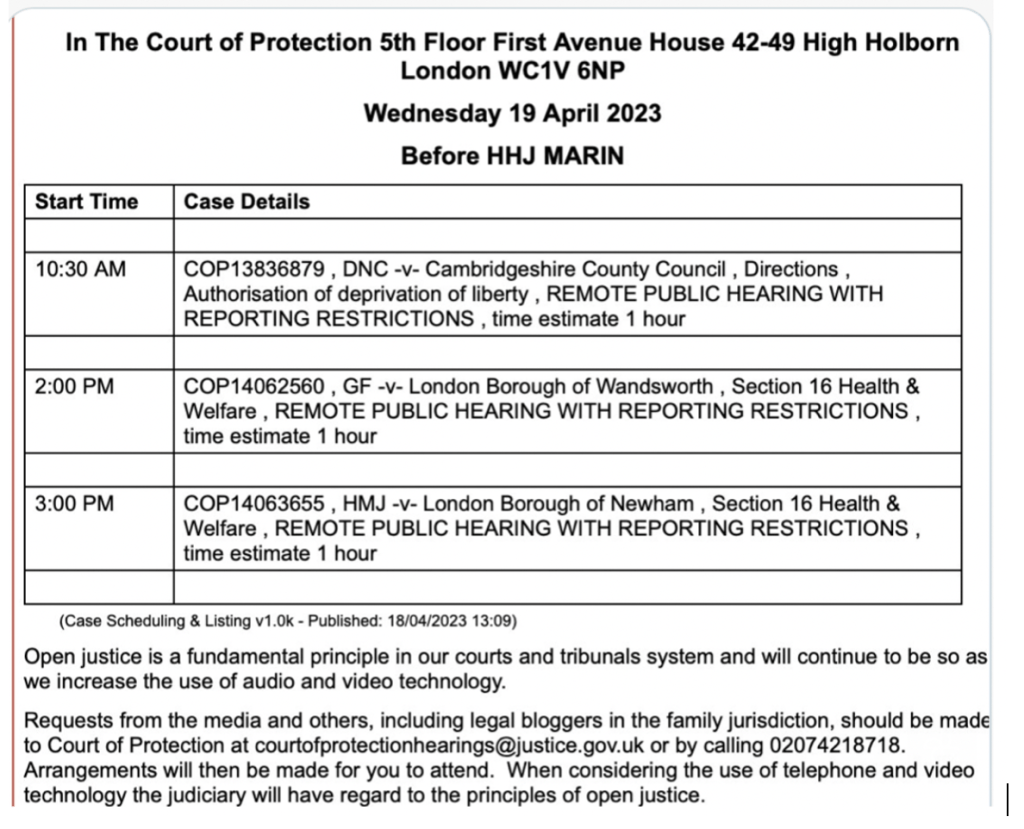

This was the third hearing in the case (COP 140113508). Bonnie observed the first two and we both observed the final hearing which was attended by all the barristers in person before Mr Justice Hayden on 21 April 2023, with the video-link for Isaac’s mother and observers.

No party was disputing that Isaac lacks capacity to make decisions about his medical treatment, so the evidence focused on what course of action would be in his best interests.

In this blog, we focus on the medical evidence before the court and how the various options were explored through the examination process. You can also read Daniel Clark’s blog on the parent’s evidence here.

Beginning the hearing

At the start of the hearing, we could see a large number of people in the physical courtroom, and were grateful that Ms Katie Gollop KC, counsel for the two NHS Trusts, introduced each in turn. In terms of counsel, also present were Mr Scott Matthewson, counsel for the Integrated Care Board, Ms Nicola Kohn, instructed by Isaac’s mother, and Mr Parishil Patel KC, instructed by the Official Solicitor, who was appointed to act as Isaac’s litigation friend. Each was accompanied by their instructing solicitor. Ms Gollop also introduced four healthcare professionals who were available to give evidence to the Court. These consisted of the consultants who either were involved in Isaac’s care, or would be involved if a transplant went ahead. Two independent experts were also involved in the case, Dr Antonia Cronin, consultant nephrologist, and Dr Steven Carnaby, a Consultant Clinical Psychologist specialising in intellectual disabilities. Isaac’s parents were in attendance virtually via Cloud Video Platform (which we also used to observe the hearing).

Ms Gollop began by explaining that prior to the hearing there had been a “productive meeting” with all parties including Isaac’s parents, and that the clinicians had answered their questions and furthered all parties’ understandings. She confirmed that the details of the issues were as set out in her position statement: however Hayden J requested that she provide an outline for the benefit of the observers, which was greatly appreciated.

Ms Gollop first confirmed Isaac’s age and diagnoses, including Williams Syndrome, that he is largely non-verbal and sensory-seeking. She explained that discussions had been taking place over the past two years as to what could be offered to treat Isaac’s kidney failure. The usual treatment would be dialysis, provided either peritoneally (via insertion of a catheter tube into the stomach), or through haemodialysis (HD), which requires attendance at hospital three times a week for a 3-4 hour session on a machine. Ms Gollop explained that peritoneal dialysis was not an option in this case, because Isaac already had a tube inserted into his stomach to support his gut (known as a Radiologically Inserted Gastrostomy or RIG), and to introduce a second would create a high risk of infection; this was agreed by all parties. The discussion was focused on HD or a transplant – or palliative care.

During the first hearing in November, all parties agreed that Isaac would be unable to tolerate HD. As Ms Gollop summarised, “he does not like going to hospital, at the time it was hard to get him to go, he doesn’t like being messed about with, he doesn’t like unpredictable noises, it has taken an enormous amount of work to get him to the state where he would accept a blood test”.[1] Concerning transplantation, the options on this front had been narrowed to organs from a dead donor (known as cadaveric donation). Donation via a family member had already been ruled out, and Ms Gollop reported that Isaac’s blood type made him less matchable for altruistic donation (i.e. receiving an organ a living donor who was not known to him). When it came to a transplant, she explained “the difficulty is not the actual operation itself, it is incredibly safe. The difficulties and risks are everything that happens around that. The work up before and post-operative period, and the post-post operative period.”

Since the previous hearings, there had been a change. With input from the Learning Disability team, “desensitisation work” had been carried out with Isaac to get him into a position to cope with going to hospital and medical interventions. This had successfully allowed him to undergo the insertion of his RIG, and meant reconsideration of whether Isaac could cope with a transplant operation. A further report had been produced by Dr Cronin, the day before the hearing, however her view (which was shared by the clinicians at Hospital X) was that the obstacles to placing Isaac on the waiting list for a transplant were “prohibitive”. This was because Isaac was not established on HD, it was doubtful that he could tolerate HD. There was a realistic prospect that some form of HD would be required post-operatively, and without this, Isaac would die. Ms Gollop confirmed that on this basis, “having considered this carefully, with regret the team at [Hospital X] is not prepared to put him on the list for a cadaveric transplant unless he is able to do HD”.

At this point Hayden J interjected, leading to the following exchange:

Hayden J: Does that mean that anyone with severe autism would axiomatically not get on the transplant list?

Ms Gollop: No, because some people with severe autism – like William Verden – are able to tolerate haemodialysis and he got on the list. It’s a bespoke thing.

Hayden J: Is it the case that anyone at this end of the autistic spectrum would not be able to receive a kidney transplant?

Ms Gollop: If autism is the reason why you can’t do haemodialysis, that’s right. But there are other reasons why people can’t do haemodialysis. And some people with severe autism CAN do haemodialsyis. It’s not “he has severe autism, ergo we can’t do transplant’. I don’t know that I’m in a position to say this.

Hayden J: It’s an important question.

Ms Gollop: No-one is saying this at [Hospital X].

Hayden: No they wouldn’t, but the result of your argument appears to mean that someone at this end of the spectrum would never be placed on the list.

Ms Gollop: Then that’s right.

Hayden J: And that’s an ethical issue that has to be confronted in this case.

Ms Gollop: And it is being confronted. It’s precisely because people are treating [Isaac] as an individual that this is being discussed. They have suggested that we reconsider his ability to undergo haemodialysis in relation to this stark fact that if he is unable to do this, then his end stage kidney failure will take over. His mother has said she sees haemodialysis as a ‘non starter’. Dr B is prepared to engage with this process against his better judgment. He is very worried about the risks

Hayden: So let me follow. Are you contemplating a further assessment of his capacity to engage in haemodialysis?

Ms Gollop: Something like that. His mental capacity won’t be there but if more desensitisation could be done then it might be possible

Hayden J: I shouldn’t be asking any doctor to engage in a process against their better judgment, nor am I likely to do so. In the context of end-stage kidney failure, there are no good options.

Ms Gollop: There are no good options here. There are questions about the demands and burdens of treatment and the effect on [Isaac]’s quality of life. [Isaac] is someone for whom routine is important. He gets enjoyment from his current routine, his visits to his day centre, going out and about, visiting people. Dialysis would interfere with that routine. It’s unpleasant and tiring. There are risks associated with it. All that needs to be weighed in the balance of choosing the least worst option for him now. It’s a question of a higher quality of life and a shorter one, or distress and medical procedures and a lot of time in hospital with the possibility of a longer life.

Hayden J: Ms Gollop, you and I have done some very complicated cases together but I don’t recall any that are more complicated than the best interests decision in this case.

This was a very important discussion and demonstrated clearly the issues that were being grappled with. It was good to see Hayden J noting the potential implications of the stance being taken by the clinicians: Isaac was said to be unable to tolerate HD as a result of his ASD, and because of this, the clinicians would not put him on the list for transplant. It could be said therefore that his autism was the barrier to him receiving treatment, and the reason why it might be decided that he should be placed on end-of-life care instead of being given active treatment. The clincians themselves are also constrained by the policies in place regarding the transplant pathway, and as Bonnie has previously written, there are significant barriers to individuals with learning disabilities accessing transplantation. As such, it was important to confront this head on when considering what the options were for Isaac. A consideration of whether he could tolerate HD seemed crucial to whether transplant could be contemplated. It was noticeable that Hayden J considered this one of the most complicated he had ever dealt with – quite the feat given his considerable experience . This comment from the judge really hammered home how difficult this case was.

Evidence from the medical witnesses

The judge then heard evidence from each of the four clinicians who would be involved in the transplant or were involved in Isaac’s treatment. They were:

- Dr A, Consultant Transplant Surgeon at Hospital X

- Dr B, Consultant Nephrologist at Trust W (who was currently involved in Isaac’s care)

- Dr C, Consultant Intensivist at Hospital X

- Mr D, Consultant Transplant Surgeon at Hospital X

We will discuss the evidence from each in turn.

1. Dr A: “It is not safe to embark on desceased donor kidney transplant as things currently stand”

Dr A gave detailed evidence regarding the transplantation procedure and allocation system. Concerning the latter, he explained that the allocation of organs is done by NHS Blood and Transplant (the specialist NHS authority) by means of a complex algorithm on the basis of seven factors, the most important of which are the time the person has been on the list, and a calculation on whether the organ is a match, for example considering blood group, age etc. He confirmed that the waiting time for an organ varies regionally, but in their local area, it is shorter than the national average, because their policy involves using organs which may have been rejected by other centres. He explained for individuals in Isaac’s blood group, the average national waiting time is 729 days, but in their local area it could be as low as 12 months.

Dr A then described the reasons that the team would not to add Isaac to the organ transplant waiting list. The first was that Isaac would need to be well enough to have a transplant when one became available, and given the timescale there was a risk he would not be. The second was “the practical business of doing it”. Isaac would need a period in intensive care post-operation, and there was the possibility of further treatment including HD. There was some discussion between Dr A and Hayden J about the post-operative environment and complications, however it was not possible to follow this because there were issues with the audio of both the judge and Dr A. The clerks in the courtroom were very responsive when we raised this issue, and with some swapping of microphones, we were able to pick up the conversation after a few minutes. Hayden J was trying to understand at this point when Isaac’s kidney function was likely to deteriorate. Dr B confirmed from the back of the courtroom that he would “fall below the threshold to start dialysis in the next 6-12 months”. Hayden J then put to Dr A:

“Taking the conservative 6 months estimate and putting it into the time frames you have given us [on transplant waiting times], it seems that there is a realistic prospect that we will know the answer to [Isaac]’s capacity to engage with haemodialysis by the time the kidney is available?”

This appeared to be geared towards exploring the possibility of listing Isaac for a transplant at the same time as the desensitisation work for HD was taking place – what Hayden J referred to as “running options in parallel”. Dr A confirmed that they would need to be confident Isaac could tolerate HD – not for the purpose of long-term treatment but so that a transplant could be offered safely. He added however that he could not place Isaac on the waiting list unless they were satisfied of his tolerance. The judge pushed him on this: “I don’t get the logic of that. If he’s on the list he doesn’t get matched, but the longer he’s on the list, the shorter the timescale.”

After some discussion, Dr A agreed that it would be possible to place Isaac on the waiting list but have him as a suspended patient, meaning he would still accrue waiting time for the purposes of allocation, but would not be made ‘live’ and able to receive an organ until the clinicians were satisfied he could tolerate HD. Hayden J summarised: “whilst it might be unorthodox, the prospect of getting [Isaac] on a suspended waiting list would be a realistic objective.” Dr A reiterated “that would be straightforward, but does not mean we are prepared to transplant him, we would need to be confident he could be safely dialysed.”

The judge then stated “in simple terms, last November, I would not have thought there was any prospect at all of [Isaac] being able to comply with haemodialysis. That was Mum’s position. [His mother can be seen nodding at this point] My thinking, which I’m stating for Mum in simple honest terms, is that it strikes me as a rather uphill struggle for Isaac to be able to achieve compliance with haemodialysis, but we do sometimes find that people surprise us. If [Isaac] could not tolerate it, the focus would then turn to establishing the best possible package of palliative care for him.”

It seemed that Dr A was also supportive of this course of action; he noted that other benefits could be accrued through the desensitisation work as it would provide reassurance that further interventions, if needed, could be attempted, such as treating Isaac for infection.

We were both pleased to see the potential for the options to be explored simultaneously, to allow Isaac the benefit of being on the waiting list to accrue time and thus be further up the list for allocation whilst the possibilities around HD were further explored. This seemed to be a reasonable way forward so as not to disadvantage him. Dr A also noted that the approach to transplantation in Hospital X potentially increased the need for post-operative HD to get the kidneys working (as they may have been in storage for longer). He noted that although another unit elsewhere might be willing to accept Isaac as a potential candidate, because waiting times vary dependent on the part of the country that a unit is in, it would be likely that Isaac’s total waiting time could be longer.

Dr A was also keen to point out that “we have transplanted patients with similar learning and psychological difficulties to Isaac’s, one of two a year he suggested, in every case they have been established on haemodialysis.”

Dr A was then cross-examined by Ms Kohn for Isaac’s mother, and Mr Patel, for the Official Solicitor. Ms Kohn pushed him on the potential that post-transplantation HD could be needed (which she stated was around 50%) and why establishing Isaac on HD was absolutely necessary: “my understanding is that you consider him theoretically fit for transplant, it is technically possible but the surrounding treatment issues are the impediment”. To this Dr A replied that they could not envisage placing Isaac on the list and then allowing him to die post-operatively because they could not dialyse: “there is a real risk of unpleasant distressing admission leading to his death with us trying, some might say recklessly, to perform a transplant.” It was again emphasised that whilst Dr A would be happy to give him the ‘advantage’ of being on the list, this is “not an acknowledgement that we think he is fit to receive a transplant”.

This line of questioning continued with Mr Patel who noted that in order to make Isaac active (instead of suspended) on the transplant list, the doctors would need to conclude that it would be safe for Isaac to have a transplant, but putting him on the list was a recognition that he might be able to reach that point (to which Dr A replied “conceivably”). It was clear from their discussion that placing Isaac on the list should not be construed as an agreement that he would get a transplant, but rather that it signalled a commitment to assessing him further following the desensitisation work. Dr A suggested 3-6 months would be a reasonable timeframe for re-assessment. Ms Kohn then finally asked “is establishment on dialysis is an essential requirement for transplant to be safe and practical a requirement [for Isaac] or for all patients?” Dr A replied “in our view the ability to perform some form of renal treatment in the peri-transplant period is essential. Otherwise, we would be in a situation where you carried out a kidney transplant and patient would die if it did not work. We could not countenance that.”

2. Dr B: “Haemodialysis is fraught with considerable risk: it is not possible to safely administer it to get him fit enough for transplant”

Dr B’s evidence, from his perspective as Isaac’s nephrologist, focused on HD. Counsel for the NHS Trusts, Ms Gollop, began the questioning by raising HD as a precondition of transplant and what the risks were. Dr B’s view that HD should not be considered came across strongly in this exchange. He stated:

“It would involve [Isaac] being stationary for 3-4 hours each time. Initially we would do it once or twice a week, but eventually it would need to be 3 times a week for 4 hours. And this would move up rather soon, it could be in a matter of weeks. If we start on HD with the intention of long-term treatment, it is with the idea of doing it 3x a week for 4 hours. Knowing [Isaac] and reviewing the clinical psychologist’s report, I do not think that’s going to be achievable. It is fraught with risk.”

Even when pushed by Ms Gollop on whether he would be prepared to offer it, Dr B replied as follows: “There is the dignified palliative route that we adopt when we know that contemplated medical interventions are going to do more harm than good. It’s an estimate how long [Isaac]’s kidneys will give him time, it’s possible he has a period of stability, if that’s years with a good quality of life, starting him on a treatment which we know might be dangerous and impact on quality of life is not sensible, and that’s a view shared collectively by the renal unit. I don’t think it would be appropriate to embark upon long-term HD.”

We both found this exchange confusing, because it seemed that Dr B was focused on the unsuitability of HD as a long-term treatment, but that was not what was being proposed here, as far as we understood the plan was to try and get Isaac to tolerate HD such that it could be given post-operatively if needed. It seemed odd then that Dr B’s evidence was heavily focused on Isaac’s inability to tolerate it in the long-term, and that he suggested that attempting it was not appropriate, even though his position as far as Ms Gollop understood was it was worth trialling. Hearing his evidence, the judge put to him:

“What was being canvassed earlier was a possibility, predicated on what he has achieved thus far, that [Isaac] might surprise us, and with the desensitisation work and increasing familiarity with hospital situations, he might manage to find a way to compliance with haemodialysis. The prospect of that is not a good one, but the question is whether it should be discounted. If it is not to be discounted, and he starts on it, what are the risks at that stage? The risks for a compliant 27-year-old on haemodialysis.

To this, Dr B responded that if Isaac did tolerate HD (and there was no physical or chemical restraint) then there are no contraindications.

At this point, the hearing was adjourned for lunch, with Dr B’s evidence to continue in the afternoon.

On our return, Dr Cronin (the independent expert) was now visible in the court room, having arrived to give evidence if needed. Further issues with the microphones again made it difficult to hear the discussion. As far as we could make out, Dr B gave evidence about how he envisaged the desensitisation work would progress to enable what Ms Gollop termed a “trial of limited haemodialysis”. This included work on getting Isaac to be familiar with the machine, having a dummy line placed on his tummy, then moving towards an actual line being put in. The judge asked some questions regarding the experience of dialysis for individuals and what would happen if Isaac was well, versus unwell when receiving it. During his responses, Dr B suggested that although Isaac appeared more cooperative recently, this could be a result of his kidney disease, which could make him fatigued. Hayden J challenged this, noting that in videos he had been sent of Isaac by his mother he did not appear lethargic and had been “full of beans”. His mother confirmed when asked that the clips had been taken recently and that “he had one taken yesterday with his carer at the day service, he was happy and boisterous”.

A discussion also took place regarding the use of sedation during HD. Dr B stated he was not willing to use chemical restraint (i.e. medication) to achieve compliance. The judge once again challenged this stance, leading to the following exchange:

Hayden J: A General Anaesthetic seems to be beyond coherent argument. But what about a situation where there had been a pattern of compliance but [Isaac] has a bad day, would you consider an oral sedative?

Dr B: Oral sedation from time to time is frequently required to bring [Isaac] into hospital, but once someone comes in, there’s a specific timeframe to start dialysis (as we understood, the sessions run at specific times in the hospital). Administering another sedative isn’t practicable.

Hayden J: What I am saying is that [Isaac] may have an inconsistent pattern of compliance. So, whilst there might be strategies for achieving compliance, he might on some occasions need sedating, would you rule that out?

Dr B: There would have to be a protocol in place in terms of what we are and aren’t prepared to do, and the anaesthetic team would need to be closely involved. Intravenous sedation is out of the question.

Ms Gollop also raised practical challenges regarding support from the learning disability team, as Isaac’s main contact in that team is only part time, and discussions were ongoing with the ICB to make plans and contingencies for this. Dr B reiterated that HD is not in Isaac’s best interests and that his parents would need to be on page. Hayden J noted to this “The Trust has tacked in a different direction, [Isaac’s mother] has got to hear about it late in the day and is absorbing as it goes along. I wouldn’t assume she’s hostile now, I can see she’s shaking her head that she’s not”. Dr B reiterated that if Isaac was non-compliant in the process, he would not prepared to attach him to a machine three days a week, but up to that he would be willing to try it. The judge asked if Dr B thought Isaac would comply, to which he responded:

“Knowing him, I don’t think he will comply. One of the things brought up is consistency of environment for [Isaac]. His environment shouldn’t change, he doesn’t like being messed around with, he doesn’t like loud noises. Even with adjustments, my viewis that he will not comply with treatment. Dialysis would need to be done in same room same time. But there would be change in staff, machine will frequently have alarms, and he may not take kindly to that. We have unexpected occurrences which result in unexpected dialysis on unexpected days, which will be disruptive. Some end up with hospital admissions, which would be in completely different place, times. There is only so much we can simulate and only so much we can aspire to in terms of consistency. It will be distressing for him and us if we cannot safely deliver it. And he is likely to have a death in a medical environment.”

Despite this, however, it seemed that Dr B would be willing to trial dialysis as the “least worst option” as far as active treatment was concerned, while also pointing out that the court could alternatively acknowledge that active treatments are not in his best interests.

Hayden J then moved to a new line of questioning and asked Dr B how well he knew Isaac. Dr B began to reply “I first assessed him in late 2019 when admitted for chest infection, he had a long stay in hospital and under my care, that’s when we identified kidney failure…” But the judge interrupted his answer “I’m not asking about how you know him medically, but about Isaac as a person”. Dr B replied that he had met Isaac once a year. This led to the following exchange:

Hayden J: Have you made an assessment of his personality?

Dr B: I haven’t bonded as much as some of the nurses. He recognises and remembers people.

Hayden J: And looking at his interactions with others, what kind of personality does he have?

Dr B: He enjoys being around certain people, people he loves and knows. He loves his iPad, he loves listening to certain things…

Hayden J: Do you know what sort of things he likes to listen to?

Dr B: [pauses] I’m sorry I can’t remember

Hayden J: Can he communicate?

Dr B: He is not verbal, he has limited insight into what is happening, he doesn’t know why doctors assess him, but he feels that a doctor is someone that he has to be on his guard around.

Hayden J: Can he interact with and tease people?

Dr B: I would say so.

Hayden: So he enjoys life?

Dr B: Yes, in its current form. But if I were to bring him into hospital 3 times a week and connect him to a dialysis machine I don’t think he would.

Hayden: What’s proposed here is that we don’t close the door on a potential transplant at this stage, but we keep it open for now. Do you think that’s what [Isaac] would want?

Dr B: I can’t pretend to know what Isaac would want.

Hayden: Well you know he enjoys life.

Dr B: Knowing [Isaac], bringing him to hospital 3 times a week is going to severely impact his quality of life. He will hate it.

Hayden: I am trying to get you away from the medical and look at the patient. [Isaac] cannot communicate his wishes and feelings in the way some 27-year-old men are able to. That doesn’t relieve me of the obligation to drill down into what I can find about him and his wishes and feelings. I’m drawing from your evidence that the man who enjoys life would want the best shot at maintaining it.

Dr B: If we embarked on this treatment he would cease to enjoy life.

We both found this interaction difficult to listen to. It seemed that Dr B was entirely focused on Isaac in the context of medical care, referring to his compliance, his insight, his behaviour, and he seemingly struggled to think about Isaac as an individual person outside the context of medical care. Whilst he was agreeing to trial HD, it was clear he had significant reservations and appeared to be even constrained by starting dialysis at certain times of the day. It wasn’t clear why this was so rigid and could not be varied to accommodate Isaac’s needs or any potential sedation.

3. Dr C – post-operative care issues

Dr C, the Consultant Intensivist at Hospital X, was the next to give evidence. At this stage, we both had to step out of the hearing at times and therefore will only provide a summary here based on the evidence we were able to observe.

Dr C’s evidence focused on post-operative care for transplant patients in intensive care (ICU), including the potential risks of distress and disorientation, the process of bringing a person out of their induced coma, extubation and regaining of consciousness. He also discussed the physical space of ICU, how many visitors Isaac would be allowed when he woke up, and the potential long-term effects of being cared for in ICU, such as post-intensive care syndrome.

During her cross-examination, Ms Kohn mentioned having spoken to the paediatric intensive care consultant involved in the William Verden case (who was known as Dr Z). Further information on his evidence during the Verden hearing can be found here. Ms Kohn explained that in the Verden case, Dr Z found it acceptable to sedate and ventilate William for two weeks, if necessary, post-transplant. Dr C was asked whether he would be confident to carry out the same treatment.

Dr C: I think confident would be an overstatement. I work in pediatrics with a different patient population.

Ms Kohn: if you had a 3-year-old who was acting up, you’d contemplate this kind of procedure, so do you have a view why you wouldn’t for adults?

Dr C: These are the first patients of this kind coming through…

Hayden J: Why is that? There’s no demographic reason why that should be the case.

Dr C: Because transplants are now being considered for groups of patients for whom it was not previously considered.

Hayden J: Yes I think that’s the only inference it’s possible to draw.

Hayden J then continued to ask Dr C about the treatment William required after receiving his transplant. During this exchange, some confusion seemed to arise relating to whether sedation and ventilation was considered in William’s case to to administer HD post-transplant. Ms Kohn referred to Hayden J to the useful diagram that was presented by Ms Victoria Butler-Cole KC during William Verden’s case which laid out the various treatment options that were being considered.

After a bit of back and forth between counsel and Hayden J, there was still uncertainty as to whether one of the options was to sedate and ventilate William to administer HD. Fortunately, Dr Cronin stepped in and provided a full explanation from her seat at the back of the court. Dr Cronin clarified that in William’s case, sedation and ventilation had been considered, as it would be required to administer plasma exchange therapy.

Here, it’s worthwhile noting that the cause of William and Isaac’s kidney failure is extremely different. William’s diagnosis of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome had a much higher likelihood of leading to graft rejection post-transplant and this would have been treated by providing one or more sessions of plasma exchange. By contrast, plasma exchange was not being considered for Isaac – in this hearing the focus was rather that Isaac might require HD post-transplant and whether he would be able to tolerate it.

4. Mr D – do no harm

The final clinical expert who presented evidence was Mr D, consultant transplant surgeon. As he later explained, a transplant surgeon’s role is primarily to decide whether a patient is suitable for transplant by looking at their anatomy, as well as, ensuring that that the transplant would be safe for the specific patient.

In Isaac’s case, Mr D had conducted his physical exam and was also involved in the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) discussions about whether a transplant would be considered safe for Isaac. Regarding the examination, Mr D explained that he first met Isaac at Trust W’s Transplant Assessment Clinic where he spent about 30 minutes conducting an examination to determine whether there was any physical reason that would not allow for Isaac to receive a kidney. Isaac’s mother assisted Mr D by providing details of Isaac’s full clinical history. Mr D told the court that despite experiencing some difficulties he was able to examine Isaac.

Mr D: [Isaac] was very pleasant when I saw him…we struggled a bit to get him to lie down to examine…it was a quite difficult to examine…but he allowed me to do it…

Hayden J: What happens when you try to get him to lie down?

Mr D: He wasn’t unhappy at all. He just didn’t want to sit down, he wanted to walk around. He just wasn’t co-operating in a way to allow me to do a full examination.

Hayden J then asked Mr D to explain why the MDT had reached the decision that they would not perform a transplant unless Isaac is able to tolerate HD whilst awake. Once again, it was emphasised that there were no contraindications except safety reasons in relation to HD. As Mr D put it, “it’s not safe to go into the process of transplant without knowing [patients] can be dialysed…it’s the safety of being able to deliver dialysis or any other therapy. It’s not something we’ve entertained previously“.

Soon after this exchange, we returned to comparisons between Isaac’s situation and that of William Verden. Hayden J noted that although there was a difference in the fact that William was established on dialysis, he thought there were similar concerns between the two, taking into consideration that there were concerns about William’s behaviour towards his HD. When making this point, Hayden J was clearly erring on the side of caution and commented on the fact that he only had a document with a few bullet points explaining Verden’s case and continued to state that these points “could hardly be reflective of such a complex case”.

Hayden J continued to push Mr D on how the MDT had reach their decision that Isaac was not a suitable candidate and put to Mr D: “In this case, you say it simply could not be reconciled with the patient’s interests, because to sedate a patient on a long-term basis throughout dialysis would be pressing your ethical boundaries.”

In response to this, Mr D explained:

“Yes, you don’t know the length of time that dialysis will take, and the question is, would we treat adults or children differently? I think if [Isaac]’s scenario had been the same as [William’s] where there was established dialysis and the referring team was saying they are struggling with dialysis, I think that is something we would entertain because dialysis is already established.”

Continuing to compare William and Isaac, Hayden J took the opportunity to (as he put it) play devil’s advocate. He suggested that if we were comparing patterns, then surely Isaac was in a more favourable position: William went from compliance to non-compliance, whereas Isaac is moving from non-compliance to compliance. Hayden J did of course emphasise that Isaac’s shift from non-compliance to compliance was primarily due to the desenitisation work that was done.

Listening to Hayden J’s explanation, it was useful to reflect on how much progress Isaac had made with medical interactions since the first hearing in November 2022. During this hearing we had heard that Isaac’s fear was deeply rooted following a procedure he had when he was fourteen, and that even as an adult, his parents sometimes could not get Isaac within a quarter of a mile of the hospital as he knew every route. Yet, the recent desensitisation work had managed to overcome this, offering a glimmer of hope and Hayden J felt strongly that we should not devalue Isaac’s progress.

He returned to the comparison that Mr D had made earlier between how children and adults are provided medical treatment, leading to the following discussion:

Hayden J: “There might be a progressive revolving understanding of the needs of adults with complex needs which is catching up with our instinctive response to offer children a chance at life. Do you think?”

Mr D: “Things evolve all the time. We’re surely doing transplant and dialysing people we would not have entertained years ago. But what we have to do, is act with the knowledge we have now, with what is the right thing and what is the safest thing. I, as a transplant surgeon did not enter transplant to not transplant people. It would be wonderful if we can transplant Isaac safely and it would be a success, but the principle is ‘do no harm’, and that is the concern.”

Mr D confirmed he was satisfied with the plan that was emerging in court, but whether Isaac could be transplanted would still depend on the success of the desensitisation work and whether Isaac could comply with HD. He confirmed that only then would the MDT be able to reconsider its approach to the potential transplant.

At this point, Ms Gollop interjected and said that she had one point to make while Mr D was providing evidence:

“[Isaac’s mother]’s solicitors had the benefit of acting on behalf of Verden’s parent and they’ve put that question directly to Dr Carnaby. They asked him ‘having provided evidence in the Verden case, do you see any difference between these two cases?‘ [Dr Carnaby’s] response was that the key difference is one of insight and understanding. Isaac’s level of disability is of such that he lacks any measurable awareness of his health condition and the risk it poses to his survival. At the time of my assessment with William he was able to engage in conversations about his kidneys – where they are, their function, and that they weren’t working as they should and the need for both dialysis and transplant. This level of understanding meant that William was able to see, to a limited extent, the need to cooperate…”

Hayden J stopped Ms Gollop and said that Dr Carnaby’s response was indeed compelling.

Following this exchange, Mr D was cross-examined by Ms Kohn who further pushed him to explain what it was exactly about Isaac’s presentation that led the MDT to make their decision. She posed the following question:

“…there are two elements arising out of this, the one is the ability to withstand dialysis and the other is the ability to understand the nature of the operation. The reality is that somebody like Isaac will not understand it. Can I take it that part of your reasoning is if a patient doesn’t understand it’s not ethically appropriate to do it?”

In response to this Mr D explained his approach and understanding of treating patients with limited decision-making capacity:

“No, the lack of understanding is the ability to cope with scenarios that arise. If there is a need for dialysis, or a need to go for a CT scan or to have another operation, if there is a level of understanding, then they may be able to comply or demonstration of complying with things that they might not understand. For instance, complying with dialysis is complying with a treatment they might not understand. To say that if someone lacks understanding, it’s not ethically right to treat them, I wouldn’t agree. Everybody has a right to medical treatment if that treatment is right and safe and proper for them.”

After this exchange, the only aspect Mr D was left to discuss was whether there were any other impediments that would exclude Isaac from transplantation. He briefly referred to the fact that there could be other issues concerning Isaac’s bladder and reoccurring infections in the past but that neither would act as a contraindication to transplant.

Isaac’s parents were the last people to give evidence to the court. This part of the hearing is covered in Daniel Clarke’s (forthcoming) blog post – but it was the first time we got a real sense of who Isaac was a person, rather than hearing medical evidence about risks, and what he might or might not be able to manage. It served of an important reminder for all parties as to whom this decision was for and the person that was at the heart of the discussion.

Reflections: the options on the table[2]

This was a challenging case and the ultimate decision made by Hayden J was that it was in Isaac’s best interests to proceed with the desensitisation work and be placed on the waiting list for transplantation, albeit in suspended form, in the hope that he will become able to tolerate HD. This plan, he found, was “far more consistent with his best interests than that which had been committed to paper before today”. The outcome was testament to the careful probing of Mr Justice Hayden to push the doctors on what the options were, and what elements of the process could be adjusted to accommodate Isaac’s needs.

Beyond these positives, however, what was apparent to both of us the ways in which the options that were available to Isaac were shaped by the doctors before the court, with certain possibilities discounted by the medics from the outset and excluded from the court’s consideration. A simple way that this happened was through three doctors simply stating they would not be willing to do certain things; they would not place Isaac on the transplant waiting list – except in a ‘suspended’ form – unless or until he is able to tolderate HD, and they would not sedate him to allow HD to take place. It is well established in case law that the court cannot force a doctor to provide treatment against their clinical judgement (see R (Burke) v GMC [2005] EWCA Civ 1003). In this instance, it meant certain options were simply not contemplated.

A number of other possibilities were also constrained, with some concerning implications for what was possible for Isaac.

- Only cadaveric donation

An interesting shift occurred from the first to the third hearing in relation to the donor options that were on the table for Isaac. Ordinarily a recipient, based on their circumstances, will be provided a choice between a living or deceased donor. A living donor can be someone the recipient knows (known as an altruistic directed/specified donor) or it can be a complete stranger (referred to as a non-directed/unspecified donor – although various other terms exist).

Back in November 2022, at the first hearing observed by Bonnie, we heard that Isaac’s sister was being considered as a potential donor. Hayden J helpfully reminded the court that if this was the case, he would have to understand Isaac’s perception of his sister’s best interests as part of his determination of Isaac’s best interests.

When we returned to court for the second hearing in December 2022, Isaac’s father had also indicated that he would be willing to act as a donor. At this stage, there was no certainty that either of these family members would be considered as a suitable candidate, but there was also no reason to believe that they would not pass the required assessments. As part of this discussion, the legal requirements to donate (as stipulated by the Human Tissue Act 2004) were also brought to the court’s attention.

It bears emphasising that in order for the donor to provide valid consent, they should not be coerced into the donation. All potential donors must initiate their own donation by either calling or sending a mail to their nearest transplant centre. Unfortunately, it was acknowledged in court (at the December 2022 hearing) that there had been somewhat of a ‘communication gap’ and that neither Isaac’s father nor his sister had understood that they had to take the first step and contact a transplant centre to indicate their willingness to donate to Isaac. This sadly meant that neither of them, at the time, had the opportunity to contact the NHS but we were told that Living Donation Information packs had been sent to them a few days before the hearing. Towards the end of the hearing, when Isaac’s father spoke to Hayden J, he profusely apologised that they had not made contact with the centre but explained there were so many emails going back and forth as part of the case that it made it difficult to stay on top of everything.

Today, however, with rather little explanation, Ms Gollop confirmed that living donation pathways were no longer being considered, either via donation from a member of Isaac’s family or via an unspecified donor. As observers, we are only able to form our views based on the information relayed in Court. It might well be that there were more nuanced discussions as to why a deceased donor was the most appropriate decision, but this information was not provided in court. Despite this, we would make two observations.

First, it was disheartening to learn in the December hearing that Isaac’s family was not made fully aware of how to approach the living donation process and the various living donation options. During the final hearing, Ms Gollop informed the court that even though his sister had been suggested as a possible donor in November 2022, some miscommunication had occurred that it was of utmost importance that pressure on the donor should be avoided. It’s worth noting that research shows that individuals often experience difficulties when first coming forward as a living donor, and it is well-documented that barriers including knowledge on donation, patient activation, and perceived social support[3] can create inequity in access to living donor transplants. No individual should feel coerced to donate an organ and if members of Isaac’s family did not feel able to act as a donor, then it is entirely correct that this option was not pursued. However a lesson that can perhaps be learned here, especially given Isaac’s father relayed to Hayden J how overwhelming the legal proceedings can be, is that families who find themselves in a similar position could benefit from additional support and guidance on how to understand and approach the donor options in a timely manner. The living kidney donation process is difficult to navigate under ordinary circumstances, and whilst it is vital that no coercion take place, guidance and support ought to be provided from the outset ensure that a person and their family are placed in the best possible position to make informed decisions regarding living donation.

Our second observation relates to the unspecified donation pathway. Research shows that unspecified donation is often not discussed as an option with potential recipients,[4] however the evidence suggested that this was explored to some extent. Dr A for example suggested that altruistic (unspecified) donors were a small number of the overall donor pool and that it was further complicated because the sharing scheme had to be taken into consideration. One option that was not mentioned in any of the hearings was the the alternative route of using a public campaign to find an altruistic donor. This method is not reliant on the sharing scheme or a donation by a family member and was initially advocated for in the William Verden case; a public campaign was launched via traditional media outlets, such as the BBC, but social media platforms like Facebook have also proved to be successful in the past. It is worthwhile to note that pubic campaigns are legally valid.

The reason why unspecified donors are often considered is because a living donation can provide for a more controlled environment. We heard in the Verden case that a controlled transplant environment is often more desirable for patients with learning difficulties and ASD – (interestingly though William eventually received a kidney from the deceased donor list). Of course we do not know whether this possibility was discussed between the family and the healthcare professionals and simply not relayed in Court. But when reflecting on how the living donation options discussed above were approached with Isaac, we cannot help but to wonder if there was perhaps a missed opportunity in this case to first exhaust all possible avenues of living donation before moving forward with the deceased donation route, or indeed run the options concurrently to maximise Isaac’s chances, as was done in William Verden’s case.

2. Transplantion only if he can demonstrate tolerance for HD

The second key limitation was the question of Isaac’s best interests in relation to transplant became inexorably linked to his best interests in relation a trial of HD, because the doctors would not list him without first establishing tolerance for HD. This limitation was ultimately accepted by the judge. It was further argued in the medical evidence before the court that no patient who could not tolerate HD would be listed for transplant – it is a standard that all patients would need to meet – perhaps as a means to push back on Hayden J’s question to Ms Gollop at the start. Whilst this might seem to be an equal approach on paper, it bears remembering that in practice, patients without learning disabilities can be listed for transplant without being established on HD beforehand. This is known as a pre-emptive transplant, and is primarily achieved by means of living donation. Due to the waiting time for a deceased donor, a recipient will often have to undergo dialysis in the meantime whilst they wait for a kidney to become available. Living donation provides an opportunity to avoid dialysis altogether, as it can be planned for in advance. In such cases, there is also a lower risk that the kidney will be rejected.

This example demonstrates that not being established on dialysis can be no impediment to receiving a transplant, most likely to our mind, that it is assumed that such patients would tolerate it if necessary. But for Isaac, because the doctors expressed an unwillingness to list him without this evidence, he is placed in a position where he needs to actively demonstrate his tolerance for HD before transplant can be contemplated. This was further justified through comparisons to William Verden and other patients with learning disabilities and/or ASD, who were all on dialysis before transplantation. When considered in this light, it seems that Isaac, and potentially others with such disabilities, are placed in a different position where they must have dialysis before transplant, and arguably must satisfy a higher threshold (of compliance) to be considered a candidate for receiving an organ. We acknowledge the evidence of Isaac’s fear of hospitals does perhaps justify the heightened level of concern, and agree that careful decision-making is required as a transplantable organ is an incredibly scarce and much needed resources given the ever-growing waiting list. But this should not mean that patients in Isaac’s position should be overlooked or that they should be held to a higher threshold when access to transplant is being considered, and indeed raises questions as to how the process could be adjusted to accommodate Isaac’s needs.

This also begs the question of what exactly Isaac would need to do to satisfy the doctors that a transplant would be safe – i.e., what level of compliance he would need to show to indicate a tolerance for HD. It seemed, listening to the evidence of Dr B in particular, that assumptions were circulating about what Isaac was or wasn’t capable of, that the plan would not work, and limitations were placed on what sedation could be given to cope with HD because of the challenges this would create in scheduling dialysis. This creates a concern that he might never be compliant to a level that the doctors are willing to make him active on the list.

The question of what a sufficient level of tolerance would look like wasn’t something that was bottomed out in the court process, or what level of variable compliance would be considered management. However, it seems important to think this through carefully, given the potential different between tolerating HD and establishing Isaac on HD. The latter adheres to the scenario mentioned by Dr B, three times a week for four hours in the long term – which nobody thought would be in Isaac’s best interests. Yet if what is trying to be achieved is getting Isaac to a point where he could manage HD post-operatively, including familiarity with the machine, an understanding of the process, this seems to require a much less intensive regime, and it is not clear why establishment on dialysis as if it was the long-term treatment plan should in fact needed here to allow Isaac to manage it after a transplant operation.

Whilst it comes as a relief that the door has not been shut to transplantation, there remains a great deal which is constrained by medical opinion and willingness. We can only hope that these questions are further explored as the desensitisation work commences, in conjunction with Isaac’s family, so he is given every chance of active treatment.

Ruby Reed-Berendt is a PhD Candidate and Research Associate at the Mason Institute for Life Sciences and the Law, Edinburgh Law School. Her PhD research analyses mental capacity law from an intersectional feminist perspective. She tweets @rubyreedberendt

Bonnie Venter is a PhD candidate and Teaching Associate at the Centre for Health, Law and Society situated within the University of Bristol Law School. Her PhD research is based on an empirically informed evaluation of the legal and regulatory framework guiding the living kidney donation pathway in the United Kingdom. She tweets @TheOrganOgress

[1] All quotations are from contemporaneous notes taken by Ruby and Bonnie, and then cross-checked with Celia Kitzinger’s notes from the hearing. Although we have done our best to ensure their accuracy, the quotations should not be taken as verbatim records.

[2] If you are interested in the question of ‘options on the table’, Beverley Clough has written about it further in her book ‘The Spaces of Mental Capacity Law: Moving Beyond Binaries’ (Routledge 2022)

[3] For more information on barriers to accessing living kidney donation see Living Organ Donation, UK Parliament POSTNOTE Number 641 (April 2021). Also see, Bailey PK and others, Investigating strategies to improve Access to Kidney Transplantation.

[4] See Zuchowski M and others, Experiences of completed and withdrawn unspecified kidney donor candidates in the United Kingdom and Bailey PK and others, Better the donor you know? A qualitative study of renal patients’ views on ‘altrusitic’ live-donor kidney transplantation