By Daniel Clark, 19th October 2025

Note: On 20-22 October 2025, the UK Supreme Court will be asked to re-visit the question of how to understand a deprivation of liberty. This is the fifth in our series of blogs about the case. The others are:

Reconsidering Cheshire West in the Supreme Court: Is a gilded cage still a cage? by Daniel Clark

Cheshire West Revisited by Lucy Series

Reform, not rollback: Reflections from a social worker and former DOLS lead on the upcoming Supreme Court case about deprivation of liberty by Claire Webster

Place Your Bets: The Supreme Court vs The Spirit of Cheshire West by Tilly Baden

Editorial note: At the time of writing this blog, it was unknown who represented the Attorney General for Northern Ireland because the skeleton argument did not identify an author. Following the first day of the hearing, it became apparent who represented the Attorney General. On 21 October 2025, this blog was updated to reflect the names of those barristers.

On 20-22 October 2025, in an application brought by the Attorney General for Northern Ireland, the UK Supreme Court will be asked to re-consider its judgment in Cheshire West. In particular, the court is to be asked whether a person’s wishes and feelings can be taken as consent to their care arrangements. For a summary of the issues in this case, see my blog: Reconsidering Cheshire West in the Supreme Court: Is a gilded cage still a cage?

There are two parties and four interveners.

The Appellant is the Attorney General for Northern Ireland, represented by Tony McGleenan KC and Alex Ruck Keene KC (Hon).

The Respondent is the Lord Advocate of Scotland, the RT Hon Dorothy Bain KC. Also acting on behalf of the Lord Advocate are Ruth Crawford KC and Lesley Irvine.

The only intervener from a governmental body is the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. He is represented by Joanne Clement KC and Zoe Gannon.

Three charities, MENCAP, Mind, and the National Autistic Society, are joint interveners. They are represented by Victoria Butler-Cole KC, Arianna Kelly, and Oliver Lewis.

The Official Solicitor is an intervener, and is represented by Emma Sutton KC and Rhys Hadden.

The Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland is an intervener, and is represented by David Welsh.

The skeleton arguments for the parties and interveners are now available on the Supreme Court website.

My approach to these summaries

This blog contains brief summaries of the position of each party and intervener. In putting together this blog, I’ve tried to capture the essence of each position but not explain every step in the formulation of that position. There is also some repetition across the documents which I haven’t reproduced.

I have tried to be fair to each party and explain their position faithfully. While I do have my own opinion about the case, I have not incorporated that opinion into these summaries.

This case concerns complex areas of law. As such, some of the language and arguments are technical and may be unfamiliar. I’ve tried to explain as much as possible. In places, I’ve quoted directly from the skeleton arguments, and only these direct quotes are marked by a reference. All references are clearly marked by “§” and correspond to the skeleton argument that I am summarising.

While this blog should be of help to people who do not have the time to read the skeleton arguments in time for the commencement of the hearing, I strongly recommend you read the skeleton arguments themselves.

At the start of this blog is a glossary of key phrases. If you’re unfamiliar with what this case is about, I recommend you read the earlier blogs (in the note at top of this page) before you read the rest of this blog.

Glossary

Acid test – This is used to identify the “concrete situation” of a deprivation of liberty. Is the person under continuous supervision and control, and not free to leave?

Article 5 – The right to liberty and security. A deprivation of liberty is through reference to Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

de facto – something that exists in reality, For example, a person assessed as lacking mental capacity to make a specific decision may de facto express their own wishes and feelings.

de jure – something recognised by law. For example, a person assessing as lacking mental capacity to make a specific decision is de jure incapacitated.

Devolution – Power given to individual nations within the United Kingdom to set their own policy and legislation. Health and social care is a devolved power. However, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 applies to England and Wales and is therefore not devolved to Wales. Northern Ireland has its own version of the Mental Capacity Act, which is (in substance) the same. Scotland has the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000.

Mihailovs – A 2013 case before the Strasbourg court, in which the court found that somebody who de jure lacks mental capacity may nevertheless be able to de facto give consent to their living arrangements. The court found that Mr Mihailovs was deprived of his liberty when residing in a care home to which he objected but was not deprived of his liberty when he gave consent to residence in another care home.

Objective element – P has been confined in a certain place for a non-negligible period of time.

Reference – The mechanism by which a nation of the United Kingdom can refer a question to the Supreme Court without the case having first been considered by the lower courts. It is the Attorney General who makes the reference to the Supreme Court. This is not an option for the UK government.

Strasbourg jurisprudence – The case law that comes from the European Court of Human Rights (which sits in Strasbourg). It is not part of the European Union.

Subjective element – P does not consent or cannot consent.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) – A UN Convention that sets out an expectation of the rights that disabled people ought to have. It has been signed and ratified by the UK but it has not been incorporated into UK law.

1. The Appellant, the Attorney General for Northern Ireland

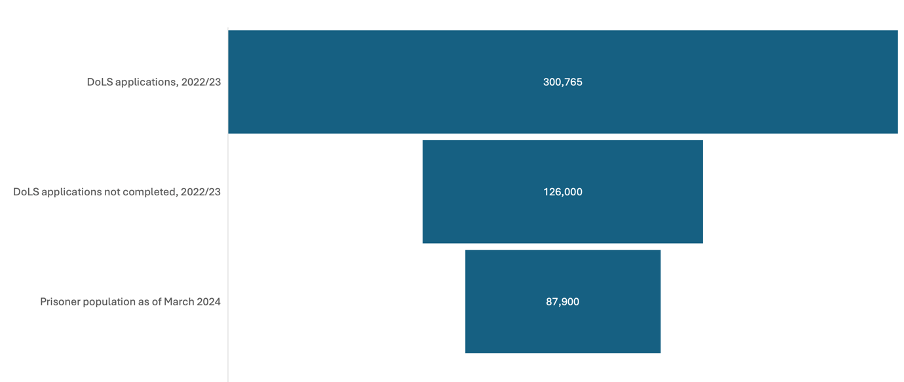

The Attorney General for Northern Ireland seeks confirmation from the Supreme Court that the Minister of Health for Northern Ireland can revise the DoLS Code of Practice in order to ‘incorporate a wider definition of ‘valid consent’ to confinement than it currently contains’ (§2). This wider definition will mean fewer people aged 16 and over will be considered to be deprived of their liberty.

The Attorney General identifies that ‘Article 5 is concerned with physical liberty, not with freedom of action in a broader sense’ (§15). In a review of the case law, the argument is made that lawful deprivation of liberty must meet three minimum conditions: a) the person can be shown to be of ‘unsound mind’; b) ‘the individual’s mental disorder must be of a kind to warrant compulsory confinement’; c) the continued confinement relies upon a persistent mental disorder that continues to satisfy b) (§17).

The Attorney General submits that there are three aspects of Strasbourg case law that mean an approach to ‘valid consent’ is required.

Consent to confinement

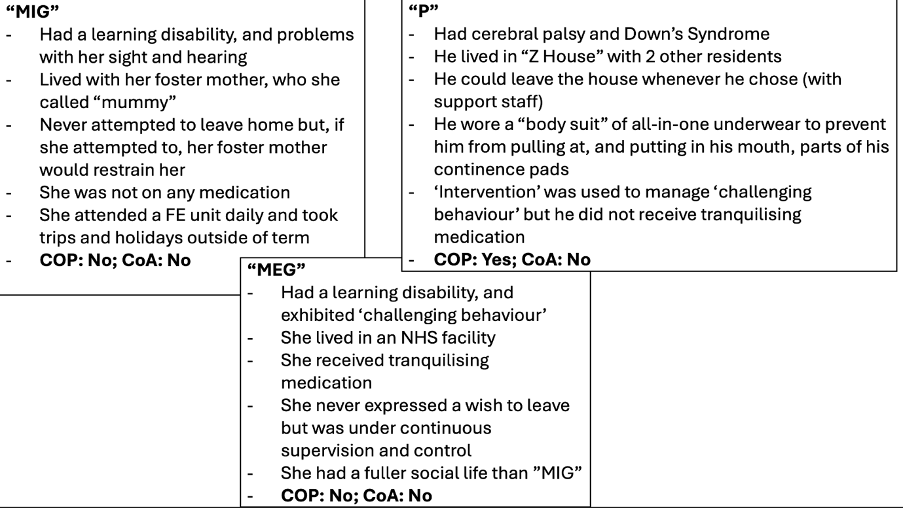

The Strasbourg court focuses on the person’s subjective perception of their living arrangements. It does not limit itself to verbal expressions. While a person may de jure lack the capacity to consent, they might de facto be able to give valid consent. In the Cheshire West case, the Supreme Court had only considered the factual circumstances, and not the ability of a person to express their wishes and preferences. In addition, it may be possible that a more ‘rigorous application’ of an approach of the Strasbourg court in Mihailovs would have led to a different conclusion as to whether MIG was consenting to her arrangements.

As such, the Attorney General takes the view that there are three issues relevant to assessing Article 5 deprivation of liberty; whether the person’s true wishes and feelings can be ascertained; whether the individual’s subjective perception can be ascertained from those wishes and feelings; that the subjective perception determines whether the arrangements are a deprivation of liberty (§34).

‘The Attorney General therefore submits that the decision in Cheshire West went beyond the boundaries of the Strasbourg jurisprudence on this particular issue. It affords no scope for consideration of the view of the person in determining whether the arrangements give rise to a deprivation of liberty’ (§35).

The Attorney General also points to concerns, expressed by judges, of the objective element. However, it is the subjective element that the Attorney General seeks to address the court on.

Coercion

The majority in Cheshire West did not address this issue. However, ‘an approach which blinds itself to the views of the person […] means that an essential step in the process of determining whether there has been coercion is excluded from the analysis’ (§39).

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Taking a wider approach to valid consent will be ‘consistent with the obligations that the United Kingdom has taken upon itself by ratifying the CRPD’ (§41). While the CRPD is an unincorporated treaty, and therefore not part of UK law, the MCA directs attention to Article 5, and the Strasbourg court places reliance on the CRPD.

‘The approach of the majority in Cheshire West appears to be the direct inverse of that required by the CRPD’ (§43).

Wider human rights considerations

- Looking at a person’s circumstances (within the DoLS framework) will engage their Article 8 rights to private and family life.

- The DoLS framework will also require engagement with the Article 8 rights of others, such as family members. This engagement ‘is undoubtedly warranted where the person is deprived of their liberty, and the assessment process is required to comply with Article 5 ECHR’. However, this requires the disclosure of sensitive personal data, including family relationships. The data must be shared, without consent of the family members, with the panel authorising the deprivation of liberty. It also needs to be involved with staff. ‘This process inevitably involves interference with the Article 8 rights of both the person and family members’ (§46). This should only be undertaken where it is strictly necessary.

- The Cheshire West approach ‘is difficult to reconcile’ with the person centred approach of the MCA, which is itself informed by Article 8, because it gives limited weight to known wishes and feelings.

- The Cheshire West approach is also difficult to reconcile with the principle that less restrictive measures are explored. It also limits the ability to make the case that the deprivation of liberty can ever be ended in a context where a person has complex care needs.

Safeguards

- The revision to the code shifts the question to whether a person’s position requires authorisation in the first place.

- There will be administrative arrangements. The relevant body will need to explain why, notwithstanding a lack of capacity, a person can be said to be giving valid consent or to seek authorisation under DoLS framework. This record of valid assent will be subject to review. If assent cannot be demonstrated at any stage, those confining the person would be at risk of civil or criminal liability. Placing a burden of proving a positive and ongoing assent ‘materially reduces the risk that providers, public bodies (and indeed) families might seek to ‘manufacture’ the appearance of contentment on the part of the person by – for instance – medication so as to mask their actual discontent’ (§55).

- This will not apply to detention under the Mental Health Act.

2. The Respondent, the Lord Advocate of Scotland

Position: The Lord Advocate of Scotland supports the appeal.

The appropriate approach to the reference

While it is desirable for legal questions to be determined against known facts (as they apply to individual cases), this is not the circumstances of this case. However, the devolution jurisdiction permits the determination of issues that might not otherwise arise from a decision by the courts. ‘The issues raised are not academic, and are not otherwise the subject of proceedings. The court is invited on that basis to proceed to answer the question referred’ (§8).

Article 5 – the subjective element

In the Strasbourg jurisprudence, the applicant challenging a deprivation of liberty was able to understand their situation in order to object. It is implicit that valid consent is a requirement for deprivation of liberty to be made out, and it follows from the case law that consent may be given and withheld.

The Mihailovs case supports the view that valid consent, and lack thereof, may be implied from an individual’s conduct. The Strasbourg jurisprudence is clear that valid consent is not provided by way of acquiesce, may be inferred from conduct but must always be freely given and properly informed.

Safeguards

These should be: objectively established, recorded, periodically reviewed, and only given following the provision of all necessary information. These are all supported by Article 12(4) of the UNCRPD.

The safeguards identified by the Attorney General ‘go some significant way towards permitting a positive answer to the question referred’ (§29). It will be important that the ‘parameters of consent (and so what constitutes a ‘deprivation of liberty’), as well as the safeguards for obtaining consent, are able to be clearly identified’ (§29).

Cheshire West

The Lord Advocate does not agree with the Attorney General that Cheshire West went beyond the boundaries of the Strasbourg jurisprudence. ‘The court did not consider the subjective element at all […] The Lord Advocate accordingly submits that Cheshire West stands as an essentially correct statement of the law, if one which, by virtue of the way in which the arguments were presented and factual position was assumed, did not require consideration of the subjective element and, in particular, the requirements for ‘valid consent’’ (§36). Accordingly the Supreme Court is asked to clarify Cheshire West but not depart from it.

3. Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

Position: The Secretary of State supports the appeal, and also invites the court to reconsider the objective element.

‘The factors that the AGNI relies upon – particularly the absence of coercion and evidence that the individual has no objection to the arrangements in question’ are actually part of the objective element; that is, ‘whether the individual is confined in the first place’ (§4).

‘The Secretary of State contends that the law took a wrong turn in Cheshire West’ (§5). If the Supreme Court disagrees, the Supreme Court is asked to agree with the Attorney General’s position on valid consent.

Article 5

The Strasbourg court has never considered a person to be deprived of their liberty if they live in an “ordinary” care home, or in the community, or in their own home. When considering whether a person is deprived of their liberty, the Strasbourg courts considers all material factors.

Post Cheshire West

The case law from Strasbourg has not adopted an acid test. Its analysis of a potential deprivation of liberty is always highly factually specific – what the skeleton argument describes as a ‘multi-factorial test’. While restrictions in social care institutions can be considered confinement, social care provision in the UK is very different, and the restrictions ‘of a fundamentally different nature to those in issue in Cheshire West, particular for MIG and MEG’.

In Ferreira, nuance was added to the acid test. The Strasbourg court does not set a distinction between hospitals and social care settings. In addition, ‘the logic of the third reason in Ferreira would apply equally to social care settings: if the “true cause” of the person not being free to leave is their underlying disability, the state is not responsible for that either’ (§34). In addition, the reasoning of Mostyn J in the case of Katherine and Lieven J in the case of SM was correct.

As a result, the Supreme Court does not even need to grapple with the issue of whether individuals who cannot leave, by reason of disability, can provide “valid consent” because they are not confined in the first place.

‘Liberty means physical liberty, including the freedom to go where one pleases. When it comes to people who are unable to do this because they are unconscious, in a minimally conscious state, or so “profoundly disabled” that they cannot conceptualise leaving, let alone physically achieve this, then the State is not depriving them of anything’ (§41). The State has positive obligations to prevent a deprivation of liberty, such as providing a wheelchair.

‘However the crucial point is that only those who are deprived of their liberty are entitled to the full panoply of Article 5 safeguards. Those who are not so deprived do not receive them. This approach does not leave those individuals without safeguards: see Annex 1. It simply recognises the reality that individuals in this situation are not deprived of their liberty within the meaning of Article 5’ (§41).

Because these groups of people are incapable of leaving, they are not receiving less favourable treatment. There is therefore no discrimination.

Coercion

The acid test says nothing about the presence or absence of coercion but the fact a person objects is relevant to the question of whether a person is confined. However, if an objection is relevant, it follows that an absence of such an objection is also relevant. If a person is unaware of their situation, or they cannot object, the fact they have not raised an objection does not explain whether they are confined. However, a positive expression that the person is happy with their arrangements is relevant.

Continuous supervision

This has been too widely interpreted. “If decisions are being made in order to facilitate the incapacitated person’s wishes and feelings, this is not “control”’ (§49). There is a distinction to be made between supporting a person to live their life in accordance with their wishes and controlling what that individual does at any time.

Type of setting

The acid test does not distinguish between the type of setting where a person receives care and treatment. Living in one’s own home makes it less likely an individual is being confined.

What should the Supreme Court do?

In Cheshire West, the court was wrong to adopt the acid test, which went beyond the existing case law, did not incorporate all the relevant factors, and created uncertainty.

The Court was also wrong to dismiss the relevance of a lack of objection.

The Court was right to conclude that liberty must mean the same thing for everyone but Cheshire Westmeans that incapacitated people are treated less favourably than those with capacity. This is because those with capacity do have their wishes and feelings taken into account ‘whereas the wishes and feelings of incapacitated persons are ignored’ (§57).

The Supreme Court should conclude that Cheshire West was wrong.

Valid consent

If the court rejects the submissions, the Secretary of State would endorse the position of the Attorney General, with certain caveats.

There could be confusion between decision making under MCA and valid consent. This could dilute the framework in the MCA. There therefore ought to be clarity that valid consent is only relevant when considering the subjective element. There would also need to be guidance for decision makers.

4. MENCAP, Mind, and the National Autistic Society

Position: The charities oppose the appeal.

The charities invite the court to dismiss the appeal: ‘Defining a de facto detained or confined person as being, as a matter of law, not deprived of their liberty, does not reduce any restrictions on them in reality – it only removes the safeguards the person has against arbitrary or unlawful detention, access to independent advocacy/representation, and access to a court to challenge the lawfulness of that detention’ (§4).

Article 5 in the abstract

If the valid consent approach is approved, the parties or intervenors would not be able to apply to the European Court of Human Rights because there will be no ‘victims’. Advocacy and representation rights in respect of Article 5 would fall away. Valid consent would affect a person’s access to justice if they disagree that they are providing valid consent.

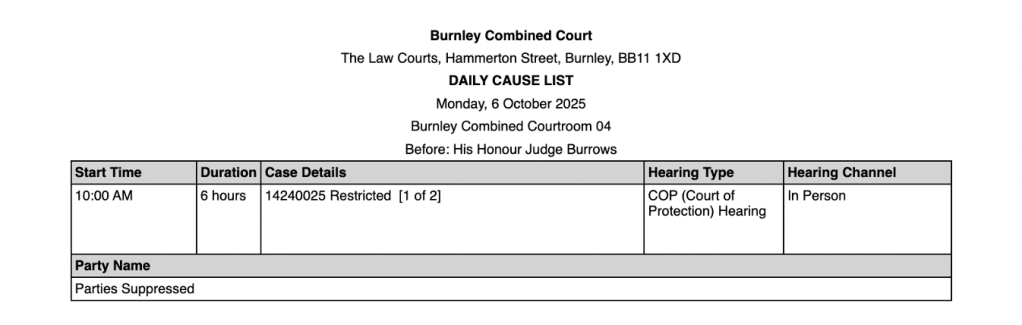

Factual context

The care arrangements for disabled people are significant. Care plans also include a range of restrictive measures. Evidence filed by the charities demonstrates that it is difficult to identify whether a disabled person agrees to such measures, objects to them, or has a positive attitude toward them.

Is a revision to the Code of Practice supported?

The Strasbourg jurisprudence shows that compliance is not enough to demonstrate consent, and valid consent has been identified where a person was found to have had sufficient understanding of their options. This is a reference to the Mihailovs case, and the charities say that this is ‘an unusual case which does not have the import in Strasbourg case law which the AGNI seeks to place on it’ (§24).

Some countries use a blanket removal of legal capacity. In these instances, it may make sense to look at valid consent. That does not happen in the UK, where assessment of capacity are decision and time specific. It therefore does not make sense to look at valid consent where a specific assessment has found a person lacks capacity to consent to a particular set of care arrangements.

Safeguards

It is right to err on the side of caution, ‘where the group of people affected are vulnerable by reason of disability’ (§31). While some people’s care arrangements will be the least restrictive possible, where there is little risk of inappropriate restrictive measures, and who do not need to exercise Article 5 rights, there will be others to whom this does not apply.

Domestic approaches to consent

The domestic courts agree that “agreement” to detention is not voluntary or valid if the consequences of withdrawing consent are that a legal framework will compel care or treatment.

Incompatibility with Article 5

The draft code is incompatible with Strasbourg case law because:

- It identifies incapacitous consent as valid;

- The consent is illusory because the person never has the freedom to leave or disengage with care;

- For those who understand the consequences of withholding consent, consent is being sought where the alternative is detention.

In addition, while a person may have a positive attitude to varying aspects of their care, they might not have a positive attitude to the restrictive measures of their care. Being happy does not necessarily correlate to contentment with these restrictions e.g. ‘people who prefer familiarity and routine may dislike being away from the place they think of as their home; or their placement may be an improvement on previous even more restrictive or even abuse arrangements’ (§40).

The CRPD

The UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities recommended, in 2017, that the UK government abolish legislation that permits substituted decision-making (which would include the MCA). The government does not intend to do so, and nor does the Northern Irish administration. In addition, the Strasbourg court has not commented on whether an expression of will and preferences can amount to valid consent for the purposes of Article 5.

Workability and protection

‘The test for valid consent proposed by the AGNI is vague, difficult to apply and likely to lead to confusion, uncertainty and differential treatment’ (§43).

Some people might agree to points made to them without understanding what is being asked of them, or in order to avoid conflict, or to mask that they are not understanding something. At §46-48, evidence from each charity is set out.

Pressure to consent

Research shows third of “voluntary” psychiatric inpatients feel “highly coerced” at admission, and a majority are unsure whether they are free to leave the hospital. Other research demonstrates that perceptions of coercion do not always match legal status.

There is an ‘inherent power imbalance’ that means some people do not raise objections or concerns because ‘they do not feel that they have any power to change things, or fear the consequences from those who have control over their lives’ (§52).

It is likely that there will be pressure (tacit or overt) on employees of care providers to see people as “consenting” where the alternative is time and cost expenditure of seeking to authorise a detention.

Safeguards

Those affected by the proposed Code of Practice will be de facto deprived of their liberty but will not be free to withdraw their consent. Without a legal framework that authorises their deprivation of liberty, they will not have access to Article 5 and 6 rights to challenge their detention.

Article 8 rights

The assessment of capacity and best interests does not cross the threshold for engaging Article 8 rights. An annual review of a deprivation of liberty ought not be more intensive than an annual care review.

If a capacity assessment does interfere with Article 8, that is necessary and proportionate. If Article 8 rights of family members are engaged, this interference is justified under Article 8(2) because it is necessary ‘for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others’ – i.e. their relative’s Article 5 rights not to be deprived arbitrarily of their liberty.

Cheshire West

The subjective element was not an issue in Cheshire West because the parties agreed that people who lack capacity to consent to care arrangements cannot give valid consent.

The SSSHC’s attempt to ask the court to reconsider the objective element is wrong.

- The reference does not raise the issue.

- It is clear what consent must attach to.

- ‘The SSHC has no power to make references directly to the Supreme Court for a determination of a legal issue in the abstract.’

- It would be procedurally unfair and improper to revisit Cheshire West because ‘interested parties have had little or no opportunity to seek to file evidence or make representations’.

- Cheshire West is not the type of case that is appropriate to revisit.

If the Court decides it can re-visit the objective element, the charities will submit:

- Cheshire West did not establish new principles.

- Community arrangements can be just as, or more, restrictive than institutional settings.

- The points made by the SSHSC were made in Cheshire West, and the SSHSC does not cite any new cases to support a different conclusion,

- Cheshire West provided a clear and workable definition of the objective element, reducing confusion for people, families, and professionals.

5. The Official Solicitor

NB This skeleton argument is an excellent resource for understanding the Mental Capacity Act, and the role of the Official Solicitor within CoP proceedings.

Position: The Official Solicitor opposes the appeal.

The Official Solicitor takes the view that the issue of the subjective element can be resolved without addressing the objective element. If valid consent is taken to have a wider interpretation, the court would expand the Strasbourg jurisprudence. If the approach of the Attorney General is endorsed, it would ‘create a two tiered system’ between those who can, and cannot, consent (§9(5)).

Article 5

‘The right to liberty is too important in a democratic society for a person to lose the benefit of Convention protection for the single reason that they may have “give themselves up” to be taken into detention’ (§24(3)).

The starting point must be the concrete situation. If a person lacks de jure legal capacity to make decisions, this does not mean they are de facto unable to understand the situation in which they are in.

Mental Capacity Act

Once a lack of capacity has been established, there is no limit to the weight (or lack therefore) that can be given to wishes and feelings. In some cases, the CoP has found P lacks capacity but left the decision itself to P. Wishes and feelings are not ignored, as the SSHSC suggest.

If valid consent is broadened, clarity is needed as to what P would be consenting to. If P agreed to accommodation, care and support, and specific restrictions – and lacked capacity to make these decisions because of an impairment or disturbance, and also could not understand the restrictions, it is unclear how that person could ‘simultaneously agree to a confinement that they have been assessed not to be able to understand. There is a fundamental difficulty with what is proposed by the Attorney General as a matter of logic’ (§47).

What is being suggested may leave P without the support of an advocate who could bring proceedings on their behalf.

Safeguards

It is not clear how the responsibility to demonstrate P is consenting being placed on those confining P would guard against unqualified control. There is an absence of any reference to an independent assessor. Article 5 protects against arbitrary detention but it is unclear how this would be addressed. It is further unclear what would happen if P changed their mind.

Response to the Secretary of State

‘The issues raised by the Secretary of State focus on (i) a separate and distinct issue to the question posed in the reference, and do so (ii) in the complete absence of a clear factual matrix. (§60).

If the court does decide to revisit Cheshire West, the OS takes the view that the decision in it should be followed. The reference to Ferreira is also not supported by evidence that its ambit (life sustaining medical treatment in hospital) has been widened such that those in receipt of social care would not have the benefit of Article 5 protections.

6. The Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland

Position: The Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland supports the appeal.

This skeleton argument provides some background to the work of the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (MWC). Its ‘overarching function […] is to act in a manner which seeks to protect the welfare of persons in Scotland who have a mental disorder’ (§2.2).

The law in Scotland

The law in Scotland has a number of mechanisms for people to make a decision on behalf of an adult who lacks mental capacity to make that decision. Most of this is set out in the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000.

In 2007, Section 13ZA was inserted into the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968. This makes it clear that local authorities have the power ‘to provide community care services, including placing adults in registered care settings where the adult lacks legal capacity to make decisions for themselves’ (§3.4).

One authorisation method is via a Welfare Power of Attorney (WPOA), which is granted by the adult themselves. It is similar to the England and Wales Lasting Power of Attorney system but ‘a WPOA will grant authority for a registered care home placement only if it includes the specific power to decide on the adult’s residence or accommodation’ (§3.7).

Where a WPOA is not in place, authorisation is made via intervention orders and guardianship orders. The existence of either order, or an application for an order, prevents the use of section 13ZA.

An Intervention Order is granted by the Sheriff Court and authorises a person to make a specific decision on behalf of an adult who lacks the capacity to make that decision. They are not used for long-term or repeated decision-making.

By contrast, a guardianship order is longer-term. It does grant the power to make a decision about residence, and consenting on the person’s behalf. The time to acquire a guardianship order is approximately three months.

Section 13ZA permits a local authority to arrange for an adult to move to a care setting if it is deemed necessary, and if the person lacks the capacity to consent to that move. When considering using powers under 13ZA, the local authority must take into account the adult’s wishes and feelings.

Deprivation of liberty

The Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 ‘understans the extent to which the expression of wishes and feelings by an adult who is otherwise lacking in legal capacity might be taken as consent for the purposes of, for example, a care placement’ (§3.27).

In Cheshire West, the judgment seems to imply that wishes and feelings should be taken into account. The Scottish legislation makes this a necessity.

The MWC sees no practical reason why a positive expression of views or feelings shouldn’t form the basis of valid consent.

‘If an adult is able to understand sufficiently to be able to express a view or feeling in relation to their placement, and that view or feeling is subject to a blanket disregard when it comes to determining the future of that placement, it is difficult to see how that does not amount to a disproportionate interference with that adult’s Article 8 rights’ (§3.35).

There would, however, be a positive benefit from judicial oversight where an adult’s expressed views do not coincide with that of the decision-maker.

In the Scottish context, section 13ZA already provides sufficient safeguards.

Daniel Clark is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. He is a PhD student in the Department of Politics & International Relations at the University of Sheffield. His research considers Iris Marion Young’s claim that older people are an oppressed social group. It is funded by WRoCAH. He is on LinkedIn, X @DanielClark132 and Bluesky @clarkdaniel.bsky.social.