By Celia Kitzinger, 23rd August 2021

I’m profoundly disturbed by this case (COP 12913981) before District Judge Beckley, which has been slowly progressing though the Court of Protection for more than two years[1].

It represents a missed opportunity for the court to engage with a vulnerable person’s best interests in a holistic way. I want to understand how this happened and what can be done to ensure that it doesn’t happen again.

One benefit of the court’s commitment to transparency (especially in a hearing like this which is unlikely to lead to a published judgment) is that it creates the opportunity for public observers who are concerned by what they’ve heard in court to offer constructive feedback, and hence contribute to the possibility of change.

The case

The question before the court was where the protected party (P) should live and receive care.

She’s a woman in her 40s, described as being in a minimally conscious state (MCS) following acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis in 2016. Since being discharged from a world-famous neuro-disability hospital with an MCS diagnosis (from a consultant who said to her father, “this is as good as it gets“), she’s been living in a specialist neurological centre for the last five years. There are some indications that she may have in fact regained consciousness (albeit with severe brain damage) and have ’emerged’ from MCS, although this cannot be known for sure one way or the other without further medical evidence.

Proceedings were issued on 17th July 2019. They concern a difference of opinion between the applicant (P’s mother) and the other parties (including P’s father who was divorced from P’s mother decades ago), as to whether P should relocate to live in her mother’s home. It has now been agreed that she should remain in the care home, with a few outstanding issues still to be resolved about various investigations and treatments[2].

In focussing solely on the issue of where P should live, the court omitted to consider a key welfare issue.

Eventually, this was raised by P’s father (who, like P’s mother, was a litigant in person). He “found the courage to broach this” in an advocates’ meeting shortly before the hearing on 30th July 2021. He believes that continuing clinically assisted nutrition and hydration (CANH) is not in his daughter’s best interests.

This has been, for him, the “elephant in the room” – the huge, uncomfortable, challenging concern that has remained unspoken throughout the last two years of protracted courtroom discussions about where his daughter should live.

He says he has never been asked for his views about what his daughter might have wanted in relation to life-sustaining treatment in her current situation.

“Nobody has ever asked me about the treatments she’s getting. It’s taken me to say to those involved, ‘why hasn’t this been done?’ It’s a very long time that [my daughter] has been in this condition.”

It doesn’t surprise me that health care professionals failed to carry out proper best interests assessments as to whether or not CANH was in their patient’s best interests and simply provided it by default, without consulting about the patient’s values, feelings, wishes and beliefs. That happens frequently. The ethos that supports treatment by default is pervasive. It was robustly challenged recently – in relation to just one particular hospital – in a supplementary hearing before Mr Justice Hayden (blogged here), but the problem is pervasive. To see yet another patient with a prolonged disorder of consciousness being treated with CANH without any apparent best interests consultation in relation to this treatment feels like déjà vu.

What makes this case different, though, is that lawyers allowed this situation to continue unchecked for two years, while questions about residence were addressed.

The Court of Protection is famously “inquisitorial”. That means that the court is actively involved in investigating the facts of the case and is not confined to dealing solely with the issues put before it. Its job is to look at the protected party’s best interests ‘in the round’.

The two barristers in the hearing I observed were Mungo Wenban-Smith of 39 Essex Chambers (instructed by Lauren Anderson of Irwin Mitchell) for the Official Solicitor and Nageena Khalique QC of Serjeants Inn Chambers, for the Clinical Commissioning Group (instructed by Munpreet Hundle of Capsticks). For both, this was the first time they had been instructed on this case, having replaced previous barristers, who had been involved over the previous two years. The failure to raise best interests in relation to CANH cannot therefore be attributed to either of them as individuals. Both are experienced Court of Protection barristers and have been advocates in several hearings I’ve observed recently concerning CANH and best interests for patients in prolonged disorders of consciousness.

So, prior to the involvement of these two experienced barristers, two (unknown to me) Court of Protection legal teams – one for the OS, one for the CCG – allowed a case about care and residence to continue for two years, without checking that the care being provided in the form of CANH was in P’s best interests – when at least one family member has been sure throughout that period that it is not what she would want for herself, although he has until very recently felt unable to say so.

For P’s father, it’s “cruel” to continue to give treatment to keep P alive in a state she would find intolerable, and any improvement in her level of consciousness would only serve to make her “more aware of her plight”. And P’s brother, also in court, expressed concern about continuing CANH without a full assessment of “what P herself would see as an acceptable quality of life”. In his view that would involve “at the very least, being able to feed herself, attend to basic toilet needs and a means of effective communication”. It is unclear to him whether or not these are achievable goals.

I don’t know whose responsibility it is to raise questions about P’s medical treatments in a Court of Protection case focussed on a dispute about care and residence. One problem may be that in fact there is nobody who can be clearly identified as having such a responsibility. Here are my reflections.

The Judge

The District Judge who heard this case, DJ Beckley, said explicitly that a decision about withdrawing CANH was “outside my scope”[3]. If a judicial decision was needed it must go before a more senior judge.

He explained to P’s father that a court hearing may not be needed. The responsible decision-maker (I think it’s probably the GP in this case, although there is also a treating neurologist who may have overall responsibility for P’s care) can make the decision that CANH is not in P’s best interests, and stop treatment, following a proper best interests consultation process – so long as everyone agrees (and – my addition – if the decision is not “finely balanced”). There would then be no need for a judge to be involved. But if there is disagreement (or if the decision is finely balanced), then the case must be heard by a Tier 3 judge and “the High Court judge would take over from me in relation to current proceedings too”.

District Judge Beckley was kind and courteous to P’s father and made a point of saying that he recognised how “courageous” P’s father had been in raising the issue of CANH-withdrawal: “I understand why this must have been a difficult statement for you to make”. It seemed to me that (within the limits of his remit as a district judge) he wanted to support matters going forward.

He said he was not aware of the national guidance about CANH and seemed to think it was not necessary that he should be, given that – as a district judge – he would not ever be in a position to make a withdrawal decision. (“This for judges more senior than me.”)

I understand his position. But if he had been aware of the guidance – and, importantly, aware of the fact that the guidance is often not followed – he could have intervened at an early stage in this case to ask for evidence from the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) that they had complied with it. There should have been minutes of a best interests discussion, including evidence of consultation with family members, showing their agreement that CANH was in P’s best interests and what P would want for herself in this situation. It seems there is no such documentation. The failure of the CCG to produce it as requested would have uncovered the problem. The CCG could then have been instructed back in July 2019 to carry out a proper best interests assessment (as they have now finally been required to do).

Routinely requesting evidence that best interests decision-making has been carried out in relation to CANH, as required by law, could provide an extra layer of protection for P, whether or not anyone is contesting it. This layer of extra protection is particularly important given evidence that there are often gaps in this aspect of care[4].

I hope that one outcome of publicising this case might be that Tier 1 and Tier 2 judges could be advised in future to be aware of the national guidance and to be alert to cases like these where CANH (or any other active intervention) is provided to a patient who cannot consent to it. It could be made explicit that they can use the inquisitorial nature of the court to inquire as to whether the proper processes have been followed to ensure that continuing CANH is in the patient’s best interests.

Legal team for the Clinical Commissioning Group

The legal team representing the Clinical Commissioning Group– or alternatively, in other cases, the Trust or Health Board – might perhaps be expected to want to know that their client is acting in accordance with law and professional guidance. The national guidance is clear as to the responsibilities of CCGs (and Trusts/Boards): they should ensure that regular best interests reviews of CANH are taking place (Box 5.3) and that these are a standard part of the patient’s annual review (Box 5.4).

Counsel for the CCG could have raised the matter of CANH with their client (even though it was a section 21A case) to check that annual reviews of best interests decision-making about CANH had been carried out as required. If there are systemic problems with doing this, they should be addressed.

In fact, just a few months before legal proceedings began, on 26th March 2019, there was a Continuing Health Care review. It was noted that “there has been little change since last review… She is PEG fed and the focus of her care is maintenance and to prevent deterioration”. If the legal team for the CCG received this review (as surely they must have), and if there was no indication that there had been any best interests discussion about whether “maintenance” via PEG feeding was in the patient’s best interests, they should surely have raised this with their client. The question of best interests and CANH was hiding in plain sight. The problem may be that a lot of section 21A cases are dealt with by junior barristers who may have no experience in CANH at all.

In the hearing I observed, I was concerned to hear how counsel for the CCG responded to P’s father when he raised concerns with current or possible future treatments other than CANH that might be life-sustaining for his daughter. These also should have been the focus of best interests decision-making. But he explained that he didn’t know whether or not his daughter would be resuscitated if her heart stopped. He remembered years ago, when she was in a world-famous rehabilitation hospital, that a consultant had shown him a Do Not Resuscitate Order but he realised that this might not apply now that she had moved from the hospital to the care home. He knew that she had already been double-vaccinated against covid, but didn’t want her vaccinated against influenza: “If it comes along and takes her away, that would be a blessing”. And he asked: “Any treatments that P gets in the future, could those responsible inform me what those are before they carry them out?”

This seems to me a reasonable request. All the treatments P receives require best interests decisions. As such, P’s father can and should be offered the opportunity to contribute to them as someone who cares for P and is interested in her welfare (Mental Capacity Act 2005, 4(7)(b)). He is an entirely appropriate person to consult.

Counsel for the CCG responded by saying: “it is too broad an ambit to suggest a need to discuss all her medical treatment. She is receiving medical treatment every day. It’s not appropriate to micro-manage the day-to-day treatment required. If we’re now throwing open this wider question of medical treatments – whether that needs to be the subject of litigation or argument is questionable”.

Nothing in P’s father’s question suggested to me that he wanted to “micro-manage” his daughter’s care. The two issues he specifically raised – CPR and flu vaccination – are appropriate topics for his input. They will also be issues addressed as part of the broader medical context within which any decision about CANH will be made.

I felt very sad for P’s father. He had finally got up the courage to express his long-standing concern that his daughter would never recover to a quality of life that she would value. He was asking whether – in that case – continuing PEG feeding was actually in her best interests. It shouldn’t have been his job to raise the question: he had been pushed into a situation in which he’d had to, because those with formal responsibility for best interests assessments (including the CCG) had failed to do so.

Legal team for the Official Solicitor

The Official Solicitor is charged with representing P’s best interests. In a case focusing on a dispute about where P should live, it is inevitable that best interests in relation to residence take precedence. But in this case, the Official Solicitor’s focus on the section 21A proceedings seems to have eclipsed other issues entirely. Should it have done? Is there a role for the Official Solicitor to consider P’s best interests ‘in the round’? Is there a way around the funding issues (e.g. with legal aid and OS representation) to enable P’s bests interests to be fully addressed?

I got the impression that the Official Solicitor felt ambushed by the new issue concerning CANH. Addressing the judge, counsel said: “I take very seriously the points [Father] has raised but my instructions for today’s purposes are focused on enquiries directed by you in this case to the more straightforward issues, frankly, as to what care and accommodation is in her best interests”.

He recognised, however, that the issue of whether CANH is in P’s best interests now needs to be properly addressed in accordance with the Guidance and “may well overwhelm these proceedings”.

Insofar as the Official Solicitor is supposed to be alert to P’s best interests, to assess them and promote them in the round, it seems that didn’t happen over the course of the last two years. I hope for a more holistic and proactive approach from the Official Solicitor in future cases.

The way forward?

In other courts (and tribunals) all sorts of decisions are made about people in prolonged disorders of consciousness – including where they should live and the kind of care they will receive – without any consideration of whether or not CANH is in their best interests[5]. But I didn’t expect the Court of Protection to go down this route. It’s extremely disappointing to see what’s happened in this case.

Section 21A hearings are very common. I am now worrying that there may have been other cases like this one, i.e. disputes about residence for patients in prolonged disorders of consciousness in which nobody raised the question of whether continuing CANH was in the person’s best interests.

People who are being provided with CANH who don’t have capacity to consent to it can potentially be at the centre of a wide range of Court of Protection hearings – concerning (for example) Section 21A, DOLS, or s.16 health and welfare cases, to list just the most common. If judges in these cases are not alert to CANH as a best interests issue, and if neither the Official Solicitor nor counsel for the CCG, Trust, or Health Board raises the issue, then health professionals’ (frequent) failures in CANH best interests decision-making are not being picked up or challenged. Patients can become the subjects of extensive and long-running Court of Protection cases in which the absence of robust best interests decision-making about CANH passes below the court’s radar. That’s what would have been the outcome in this case, had P’s father not intervened.

If in fact nobody – not the judge, not counsel for any party – can be held responsible for raising a question about CANH in court cases like these, there will be many cases where the “elephant in the room” remains unaddressed. This leaves the court dealing with matters of secondary importance, deflecting it from engaging with a fundamental ethical question that should be at the heart of the case. What can be done?

It is desperately sad to find that a vulnerable adult has been given medical treatment that may be contrary to her best interests over the last two years, in part because neither the judge, nor any of the solicitors and barristers involved in this case over the previous two years, thought to raise the matter.

The plan in this case, as outlined by Nageena Khalique QC, is that the CCG will instruct an independent expert and set up a best interests meeting within a matter of weeks to consider the issue of clinically assisted nutrition and hydration. If all parties agree as to a clear way forward in P’s best interests there will be no further court hearings on this matter. Alternatively, the matter will come before a Tier 3 judge as soon as possible[6].

Best interests meetings about the PEG should have been routine for this patient. This course of action should have been taken years ago.

The GP, the treating neurologist, the care home, and the CCG bear a heavy responsibility for not having ensured that the decision to prescribe clinically assisted nutrition and hydration was kept under review.

The Court of Protection bears a heavy responsibility for allowing the question of where P should live to eclipse her wider best interests for so long.

I have learnt to expect more of the Court of Protection.

I hope some consideration can be given to what has gone wrong in this case, and how the court can ensure that nothing like this happens again.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director (with Gill Loomes-Quinn) of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and co-director (with Jenny Kitzinger) of the Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre. She tweets @KitzingerCelia

[1] I chose to observe this hearing (via MS Teams on 30th July 2021) because P’s father had contacted me a few days earlier for support with ensuring that his daughter’s best interests were addressed. I explained this in my letter to the court asking to observe the hearing. In reporting on this hearing, I have drawn only on the position statements and hearing itself as I would normally do as a public observer blogging from the Court of Protection – with one exception. The phrase “the elephant in the room” is one P’s father used both in an email and in later conversation with me via Zoom. He did not use this phrase in court, but gave me permission to use it in this piece. (I also spoke with P’s brother before the hearing, but again have drawn only on what he said – or was publicly quoted as having said – in court.)

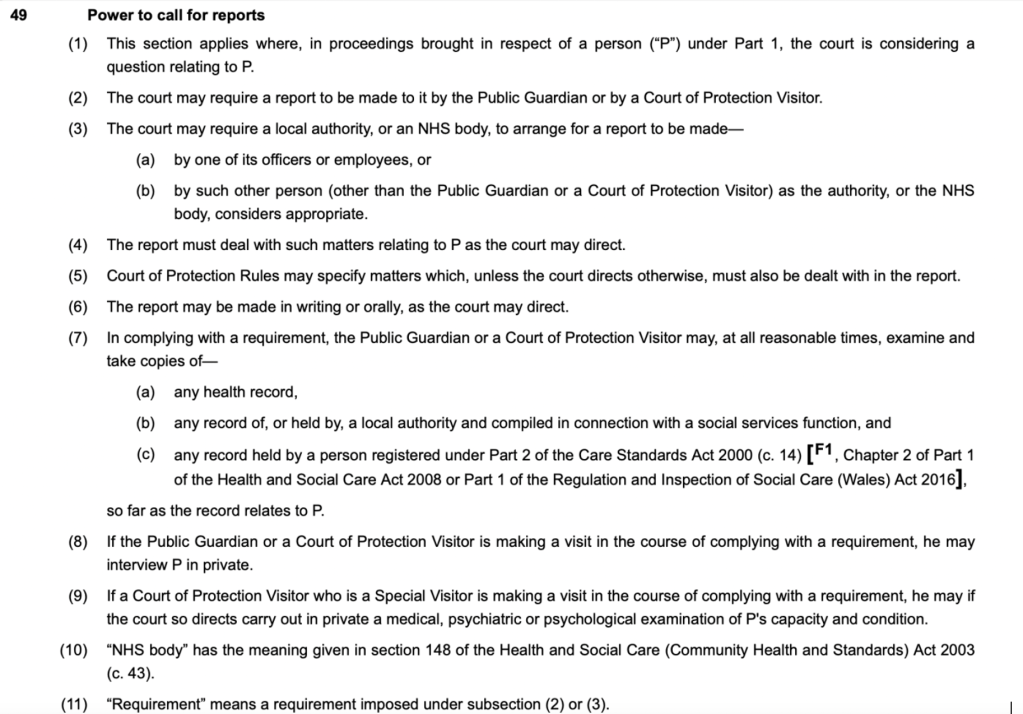

[2] The fact that it has taken in excess of two years since proceedings were issued on 17th July 2019 to come to a decision about P’s residence is also concerning. There were 8 months between issuing proceedings and inviting the Official Solicitor to act as litigation friend. The first hearing at which P was represented was 11 months after proceedings were issued (proceedings having been reconstituted as s.21A). At that hearing, a report was requested about P’s diagnosis and rehabilitation potential. The treating neurologist declined to provide one, so 2 months later a neuro-rehabilitation consultant was asked to provide a s. 49 report. She requested further medical records, requiring an additional third party disclosure order – and then went on sick leave, eventually providing the report 7 months after having been instructed. While waiting for the report from the consultant, three hearings were vacated – in January, March and May 2021. The hearing I observed on 30th July 2021 was two months after the report had been received – and it was 2 years and 13 days since proceedings were issued.

[3] We are not allowed to audio-record court hearings so where I’ve quoted what was said in court I have relied on notes made at the time. They are as accurate as I can make them, but are unlikely to be word-perfect.

[4] See Wade, D & Kitzinger, C (2019) “Making healthcare decisions in a person’s best interests when they lack capacity: clinical guidance based on a review of evidence”, Clinical Rehabilitation; Kitzinger J & Kitzinger C. (2017) Why futile and unwanted treatment continues for some PVS patients (and what to do about it) International Journal of Mental Health and Capacity Law. pp129-143; Kitzinger, J & Kitzinger, C (2016) Causes and Consequences of Delays in Treatment-Withdrawal from PVS Patients: A Case Study of Cumbria NHS Clinical Commissioning Group v Miss S and Ors [2016] EWCOP 32, Journal of Medical Ethics, 43:459-468. Kitzinger, C and Kitzinger, J (2016) ‘Court applications for withdrawal of artificial nutrition and hydration from patients in a permanent vegetative state: Family experience‘, Journal of Medical Ethics, 42:11-17.

[5] See for example this case before an immigration tribunal, and the numerous cases heard on the Queens Bench involving financial settlements and calculation of life expectancy (e.g. the case of the young man catastrophically injured by a negligent driver here or the 18-year-old injured as a passenger in a car driven by her boyfriend here). I have been told by two members of different families previously involved in cases involving financial settlements that when they raised the question of whether CANH was in their relative’s best interests, they were advised by lawyers to wait until the financial issues had been agreed (in both cases, this meant several years) before raising the matter with treating clinicians. And although treating clinicians should have raised the matter with the families concerned, they did not.

[6] In explaining the future course of action to P’s father, DJ Beckley said (twice) that if it was not possible to reach agreement in a best interests meeting, then “it is open to any of the parties to make an application for withdrawal of CANH”. This is factually correct, but the national guidance states: “Where an application to court is needed, proceedings should be initiated and funded by the relevant NHS body responsible for commissioning or providing the patient’s treatment. In Wales this will be the Health Board. In England it will be either the CCG or the NHS Trust depending on where the patient is being treated. This is particularly important given the high cost of legal proceedings and the lack of legal aid available for families to take such cases” (p.40, section 2.9). It would have been helpful if the judge had made clear that it was the responsibility of the CCG to make the application in this case (although I suspect the current counsel for the CCG already knows this). It’s also important to note that the application does not have to be “for withdrawal of CANH” (as the judge put it), but rather for a determination of P’s best interests in relation to CANH – which means that an NHS body wishing to continue CANH, or taking a neutral position, is equally responsible for making an application to the court where there is a disagreement about best interests. This may seem a small point and the all counsel in this case may well already have known the proper procedure to follow, but I’m concerned that judges should understand and communicate the recommendations in the guidelines accurately to family members, who may well be daunted and deterred by the prospect of having to make an application to court.