By Celia Kitzinger, 10th March 2024

The judgment has now been published and is available here: Rotherham and Doncaster and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust v NR & Anor [2024] EWCOP 17

The 35-year-old woman (NR) at the centre of this case (COP 14216100) is 22 weeks pregnant, and currently detained under s.3 of the Mental Health Act at a psychiatric hospital in Yorkshire.

The Trust brought the case to court because NR was said to be “consistently wishing to terminate her pregnancy but had been assessed as lacking capacity to make that decision”.

At a best interests meeting on 26th February 2024, it was concluded that it was in her best interests to undergo the termination, and that the requirements of the Abortion Act 1967 were met.

The case came before Mr Justice Hayden a few days later on 29th February 2024 (at a hearing I didn’t watch). The Trust had made an application for an order declaring that NR lacked capacity to make her own decision about termination and that termination was in her best interests.

I understand that what happened at that hearing was that the judge directed the parties to file more evidence – including about the circumstances of NR’s previous termination, and the circumstances of her two daughters having been taken into care. He also wanted more evidence about NR’s wishes and feelings. The hearing was listed to continue on 5th March – and as it turned out ran over on to 6th March as well (and I watched both days).

It was a painfully difficult hearing, with sometimes conflicting and uncertain evidence, claims that were not always supported by the written records, and a judge who was very unhappy at any prospect of over-riding NR’s autonomous decision-making, even if she in fact lacks capacity to make this decision for herself.

Unusually for a judge well known for declaring that “delay is inimical to P’s best interests”, this hearing was extended, and the judgment delayed, because he wanted to be sure to “get it right”. The termination, originally provisionally scheduled for 7th and 8th March, had to be rearranged to accommodate the delay. “I don’t think I’ve ever pushed back a procedure before on the basis of me requiring time to think, but I do feel in this case very comforted by the fact that I have more time” (Judge).

In the end, the judge issued an order declaring that

- NR lacks capacity to conduct the proceedings and to consent to undergo a termination of her pregnancy.

- It is lawful for NR to undergo a termination of her pregnancy in accordance with the attached Care and Conveyance Plan.

It stops short of saying (as the Trust had originally sought) that termination is in NR’s best interests. The words “best interests” are not in the approved order.

The “Care and Conveyance Plan” incorporated into the order makes clear that NR’s agreement and cooperation is required at every stage – from getting into the vehicle to take her to hospital for a termination, to taking prescribed medication, receiving an injection to stop the foetal heartbeat, and accepting general anaesthetic for the removal of the foetus. If she says she does not want this, the care and conveyance plan will be stopped at any point (up to foetal death/ general anaesthesia).

The judgment has already been published (click here: Rotherham and Doncaster and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust v NR & Ors. [2024] EWCOP 17) and provides a full account of the judge’s final reasoning as well as extracts from the care notes (also displayed on screen in court) upon which some of his reasoning was based. I recommend reading it.

Given the availability of the judgment, what I want to do here is focus on my experience of observing the hearing as it unfolded in real time. It shows the different avenues the judge explored and how he approached the dilemma he was presented with in court. The things the judge said in court are his “working out” of the – somewhat surprising – solution he eventually arrived at in the approved order.

The hearing

My overwhelming impression of the hearing from start to finish was that Mr Justice Hayden was extremely uncomfortable with the idea of ordering that NR’s pregnancy should be terminated in the absence of strong and clear evidence that that’s what she wanted. The problem was that although the initial position of the applicant was that NR wanted a termination, the evidence turned out to be much more equivocal.

It became clear, to varying degrees, to everyone in court that NR was deeply conflicted about whether or not to continue her pregnancy. Between mid-January, when she was admitted to the psychiatric hospital and early March in the days before the court hearing, she is recorded as having said (for example): “I don’t want to kill it (baby) but I can’t keep it, cause I am not well“; ” I don’t want this baby […] I am not happy about killing I can’t look after it, but I can’t kill it“; “I can’t kill it, please don’t let me kill it but I don’t want it either. I can’t make this decision I don’t want to make this decision It’s too late but I can’t keep it“; and most recently (on 4th March) “I don’t want to kill it but I can’t keep it and I don’t want it to go into care, so I’ve got to get rid of it“.

As counsel for the local authority said “NR finds herself between a rock and a hard place”.

Summary of the case

The hearing began with a summary from counsel for the applicant Trust, Parishil Patel of 39 Essex Chambers.

He said that NR has had a “chaotic” life, including cocaine and alcohol abuse and that she was a victim of domestic violence from the father of her two children.

Following previous admissions (with a range of diagnoses including psychosis, emotionally unstable personality disorder, and depressive disorder), she had been receiving care in the community. But in mid-January, she discharged herself from community mental health services, stopped taking her medication and became very unwell, such that she “needed to be detained”. Since then, she has been “severely agitated, at times very abusive and very confrontational, such that she required a period in seclusion for her own benefit and for the protection of other people”.

According to counsel for the Trust, it was discovered on admission to hospital that she was pregnant and she has “consistently said that she does not want the baby”. However, he acknowledged that “the evidence is not as unequivocal as one might see”.

NR wasn’t in court and I don’t think she’d spoken to the judge either. It says in one of the position statements that she’d been offered the opportunity and declined. She was represented by her litigation friend the Official Solicitor, with Katie Scott of 39 Essex Chambers as counsel.

The local authority was represented by Leonie Hirst, Doughty Street Chambers.

Capacity

The relevant information that a person must be able to understand, retain and weigh if they are to be found to have capacity to make a decision about abortion is:

a. what the termination procedure involves (‘what is it’)

b. the effect of the termination procedure/the finality of the event (‘what it does’)

c. the risks to their physical and mental health in undergoing the termination procedure (‘what it risks’)

d. the possibility of safeguarding measures in the event of a live birth.

(from §52 S v Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Trust [2022] EWCOP 10)

If the judge had found that NR had capacity to make her own decision about termination, then the court would have had no jurisdiction. The decision would rest with NR and not with the judge.

In the published judgment, the issue of NR’s capacity – and the finding that she lacks it – is dealt with quite quickly, but this occupied quite a lot of time in court. Counsel offered on a couple of occasions to seek an new independent capacity assessment, but the judge never requested that.

Mr Patel said that NR lacked capacity to consent to a termination of her pregnancy due to her “mania” which meant she was unable to understand the information relevant to making a decision about termination, in particular “what the termination procedures involves…(‘what it is’)”. This seems to have been because (as Hayden J says in the judgment, §12) “she was completely adamant that she did not want to know anything about what would actually be involved”.

In court, Hayden J did not see this as necessarily signalling NR’s lack of capacity:

“There are certain things she says about feeling that the pregnancy is at such a stage that she’s carrying a little person and her inner conflict about terminating a little person, which seems to me to go pretty directly to understanding the concept of a termination. The fact that she doesn’t want to know anything about the details doesn’t seem to me to go to lack of capacity.” (Judge)

The Consultant Psychiatrist who gave evidence in court described NR as “unable to understand the details” about the termination procedure because “agitation and distress overwhelm her and prevent further information from being shared”. He said that she was “pacing the room, putting her head in her hands and just struggling and not being able essentially to perceive and assimilate the information that’s provided”.

Judge: I can see she becomes agitated and disengaged from the issue. You appear to infer from that, that she’s not able to assimilate and weigh what’s involved. It seems to me she may just not want to have the conversation. There’s a difference between not engaging with the mechanics of the termination and not being able to understand and weigh it.

Psychiatrist: I agree with that Your Honour.

Judge: So where does that take us in terms of her capacity?

Psychiatrist: Her distress and agitation was such that she was unable to talk about it. It didn’t feel like she was seeking to disengage. It felt was though she was incapable of engaging.

The psychiatrist’s evidence, based on a capacity assessment on 23rd February 2024, seemed somewhat different from the attendance note recorded more recently by the Official Solicitor’s agent (Lauren Crow of MJC Law) from which it appeared that NR been able to engage in a conversation of about an hour on the subject of termination. “It would appear therefore that NR is currently presenting differently to how she was 10 days ago”, said the Official Solicitor, raising the possibility of a more up-to-date capacity assessment.

Judge (to psychiatrist witness): From what you’ve read [from Ms Crow’s attendance note for the Official Solicitor], if there was another assessment of capacity is there anything here that makes you think there is any likelihood of her engaging with the mechanics of termination.

Psychiatrist: Possibly. The main piece of evidence is she appears to have been able to tolerate a conversation for a longer period without reports of her becoming distressed and overwhelmed.

Counsel for the local authority (Leonie Hirst, Doughty Street Chambers) asked the witness “I wonder whether it is easier for her to discuss pregnancy with female professionals rather than males, and you in particular as the responsible clinician?”. “Possibly”, he replied. There also appeared to be a possibility that NR’s mental health condition – and with it, her ability to engage in reflection about the choices facing her – may have improved in the couple of weeks since the psychiatrist had seen her since she’s apparently been compliant with medication.

There was an additional concern: the available options for termination (i.e. medical or surgical, and where) had not been identified at the time the psychiatrist’s capacity assessment was done, so even if she had been well enough to receive that information (which admittedly she probably was not), the capacity assessment could not have been predicated on providing NR with all the relevant information.

The concern then, as expressed by counsel for the local authority, was: “If Your Lordship decides the presumption of capacity is not displaced on the basis that the relevant information has not been presented, we’re in a very difficult position in that she may well lack capacity but there hasn’t been an Act-compliant assessment which permits the court to reach a sufficiently robust determination that she lacks capacity to make a decision about termination”.

The judge ended the first day of the hearing by sharing some of his current thoughts with counsel.

Judge: If we get into the realm of best interests, well that I really struggle with. I’m uneasy that there has been a professional assessment of what is right for her and a failure to consider her consistent expression that she doesn’t want to kill the baby. And if I find she is ambivalent, vacillating, perhaps torn between her head and her heart, that’s not a space for a judge to take a decision. I don’t think I should be doing that.

Counsel for LA: The court is obliged to make that decision because there is nobody else to make that decision.

A similar exchange followed shortly afterwards.

Judge: If she is unable to resolve this issue, I’m not obliged to resolve it for her. If I find she is genuinely riven.

Counsel for LA: It is a best interests question. Her wishes and feelings are not determinative

And as the hearing on 5th March ended (close to 5pm) the judge was still reflecting on the evidence about NR’s wishes and feelings seeming “absolutely balanced” between wanting and not wanting a termination with “challenges for her in either direction”.

“Let’s be honest about it. Those are my thoughts. They’re not particularly helpful. It isn’t helpful, I know it isn’t. I’m not persuaded that I need to adjourn for another capacity test. If I find she does not have a settled view, that seems to me to be the most natural reaction of any woman. And I don’t think it’s the role of the Court to decide upon a termination where the woman herself is ambivalent. That seems to me to be judicial overreach.” (Judge)

NR’s wishes and feelings

A lot of time on 6th March 20024 was spent on the details of the care plan – much of which was put up on the screen in the court, so everyone could see it. It was explained why it would be necessary for her to travel for 4 hours to a hospital that could carry out the abortion, the details of what was involved and the different ‘stages’ of the medical procedure. That plan is also laid out, in detail, in §38-§41 of the judgment.

The position of the Official Solicitor, also reflected in the approach of the judge, was that the wishes and feelings of NR as to whether or not she wants a termination should be determinative. The problem was identifying just what those wishes and feelings were.

The Official Solicitor had pointed out that following the hearing there would be further opportunities for NR’s views to be canvassed – including via a discussion with the team at the London hospital the evening before she was due to travel there, and once she arrives there, via discussions with the medical team at the hospital.

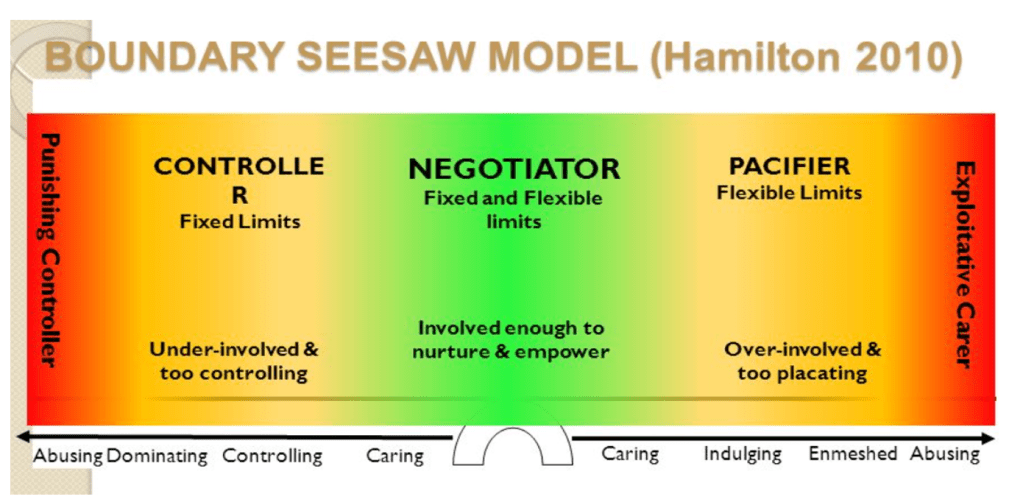

What was now clear at the beginning of the hearing on 6th March was that the plan had evolved into something that would only be implemented with NR’s agreement. If she objected to going through with any part of it, the people supporting her would discuss it with her and try to ensure that she was thinking things through and saying what she really wanted – and if she clearly indicated that she didn’t want it, then implementation of the plan would stop.

Judge: The Trust position is that if she didn’t want the termination, it would not be in her best interests to have it?

Counsel for the Trust: Yes, if she indicates she doesn’t want it, and doesn’t want it to go forward, then it shouldn’t happen.

A lot of time was then devoted to going through the notes to find exactly what NR had said, particularly recently, that might help with determining what her wishes and feelings are.

The judge drew attention to “the quality of her expression, which is graphic, moving and pleading, ‘don’t let me kill it’”.

There’s the same graphic quality when she says “I have to get rid of this baby”, said counsel for the Trust. “And there’s also a perception that if she were to carry this baby to term, it will harm her”.

He showed the judge the place in the records where NR talks to her Independent Mental Health Advocate (IMHA), who asks “Are you wanting to keep the baby?” “No”, she replies, “get rid of it!” And later, “I am not having it, because I can’t cope…. I just want to get rid of it”.

The published judgment reproduces, in detail, many of these conversations. They make painful reading.

Judge: Are you saying her wishes and feelings are so conflicted as to be unascertainable?

Counsel for Trust: It doesn’t feel like they’re unascertainable. It feels like we know perfectly well what she’s saying, but it appears that what she’s saying point in different directions.

Judge: Any woman- What I can’t see is that the material placed before me points to her wanting a termination, as opposed to being highly conflicted about it.

The judge found it “treacherous terrain” to extract from the evidence that what NR wants is a termination. Here’s how he puts it in the judgment:

“NR finds herself on the horns of the most invidious dilemma. She clearly, and most probably correctly apprehends that if she carries the baby full term, it will be removed from her at, or shortly after birth. This may even be her wish, though she plainly anticipates the possibility of being ambushed by her own emotions…. Equally, she plainly contemplates a termination, even though that may not sit easily with her prevailing beliefs. Ultimately I do not, as I have said, find that the evidence in this case supports a determined view either to terminate or to continue with the pregnancy. The evidence, in my judgment, reflects a woman who is paralysed by conflict, which is pervasive. […] … I am entirely satisfied that it would be wrong and unsafe to draw a concluding view as to what NR’s wishes and feelings truly are.” (§37)

At the end of the hearing, the judge said: “The cases that come before this court are sometimes at the very parameters of ethics, law, medicine, and jurisprudence. I have found this an extremely difficult case to hear – not least because it is, in its own unique way, profoundly sad.”

Reflections

This is the first time I’ve watched a hearing about terminating a pregnancy. Some of the issues raised were very familiar to me from other serious medical treatment cases I’ve observed (especially those relating to place or mode of childbirth) – in particular the sense of urgency that pervaded the hearing. What was unusual was the position taken by the Official Solicitor that the protected party’s wishes and feelings should be determinative, and the way in which that was incorporated into the judge’s order. I checked out the case law on pregnancy termination to try to understand how an incapacitated person’s wishes and feelings had been previously considered in termination cases.

Urgency and Delay

The issue of delay is often raised in caesarean cases – why didn’t the Trust apply to the court earlier, given that a woman’s mental health status, her likely lack of capacity to consent, and the probable advisability of a caesarean can often be predicted months ahead.

In this case, there was no rebuke from the judge suggesting that this case should have been referred to court earlier, so perhaps there are good reasons why it wasn’t, but I am concerned that (according to the Official Solicitor) NR had been expressing a desire to terminate her pregnancy since her admission to hospital on 16thJanuary – and it had taken six weeks for professionals to reach the view that she lacked capacity and to arrive at best interests decision for her, and then to get the case to court. That seems quite a long time, given the advancing state of her pregnancy and the cut-off of 24 weeks for termination under the law.

I am not sure why cases concerning termination of pregnancy come so late to court – at 22 or 23 weeks in other cases also (Re S before HHJ Hilder, Re SB before Holman J, and Re AB before Lieven J). It means that judges are under immense time pressure (as also routinely happens with cases where women are refusing – or might refuse – caesareans). Several judges have pointed out that they have been placed in a position where they’ve had to write their judgments in a hurry and have not been able to spell out their reasoning in as much detail as they would like.

The Court of Appeal (in Re AB) advised that applications in termination cases should be treated with the utmost urgency by treating clinicians and court listing officers. Where there was any concern that an application may become necessary, the treating Trust should make an application, obtain a listing (for a final hearing) and then withdraw the application, if a consensus with the Official Solicitor/patient’s family was reached.

Wishes and feelings as determinative

What seemed very different in this termination case compared with the caesarean cases (and indeed almost all other Court of Protection hearings I’ve watched) was the extent to which the protected party’s wishes and feelings were placed first and foremost in the best interests consideration – to the extent that, in his judgment, Hayden J says that NR’s best interests are that “this decision should be NR’s” (§46).

In the Order, Hayden J doesn’t identify what NR’s best interests are at all. He merely declares that she lacks capacity and that it would be lawful for her to undergo a termination of her pregnancy in accordance with the Care and Conveyance Plan (which requires her agreement every step of the way).

It’s very unusual for a judge to say that a protected party lacks capacity to make a decision and then, in effect, to hand that decision (or choice) back to the protected party to make. It means that an incapacitated person’s wishes and feelings determine the outcome.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 says that the person’s past and present wishes and feelings should be a component of best interests decision-making about them (§4(6)) and it is absolutely usual for judges to refer to this section of the Act and to ensure that evidence is presented in court about what those wishes and feelings are. The extent to which the person’s wishes and feeling weigh heavily in the resulting judicial decision is variable, depending on all the circumstances of the case.

There seems to me to be emerging case law – see below – that puts much greater emphasis on the wishes and feelings of a pregnant woman in relation to termination than is usual in other cases. Indeed, some lawyers (like the Official Solicitor in this case) and some judges (see below) have suggested that these wishes and feelings should be determinative.

Case law

When a pregnant woman has capacity to make her own decision about whether or not to have an abortion then (within the law and subject the agreement of doctors), the decision is her and hers alone.

There have been previous cases in the Court of Protection where judges have decided that the pregnant woman had capacity to make her own decision. In Re S and Re SB the women themselves were requesting terminations. The position of the professionals caring for them was that they did not have capacity, and that it was in their best interests to continue with their pregnancies. In both cases, the judges decided that the women were capacitous and could decide for themselves.

The fact that a woman may feel conflicted or ambivalent about continuing or terminating a pregnancy does not render her “incapacitous” to make that decision.

As the judge pointed out, the dilemma faced by NR is not unusual for women seeking an abortion. It is a hard thing to be 100% sure of. It is common to feel unsure and to have doubts. As the judge said in Re S:

“I am conscious that S may not yet have reached a final decision as to whether she wishes to terminate her pregnancy or not. She has told clinicians that she is 70 or 75% sure. ….. It is not necessary that she is “sure” … of what her decision will be for her to retain capacity to make the decision. Perceived ambivalence will doubtless inform the opinion of any clinician asked to undertake the termination procedure as to whether the statutory conditions are met but I do not consider that S’s expression of less-than-certainty amounts to inability to make a decision. Rather, in my judgment, it reflects S’s understanding of the magnitude of the decision she contemplates. The reality is that no one can reassure S that things “will work out fine” if she has the termination or if she does not. Decisions have to be taken without the benefit of a crystal ball.” (§59 S v Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Trust [2022] EWCOP 10)

When it’s determined that a woman does not have capacity to make a decision for herself about termination, then (in accordance with s.4 MCA), her wishes and feelings are normally considered as part of a best interests analysis – as in this decision by Mrs Justice Lieven in Re AB.

“AB’s wishes and feelings are plainly a relevant consideration. There are cases where wishes and feelings would be determinative, even where the person had no capacity. If AB’s wishes and feelings were clearly expressed and I felt she had any understanding (albeit non- capacious ones) of the consequences of giving birth, I would give them a great deal of weight. However, AB’s wishes are not clear. She likes being pregnant, she would probably like to have a baby, but she has no sense of what this means. As I have said I think she would like to have a baby in the same way she would like to have a nice doll. I just do not feel I can give very much weight to those expressions of wishes and feelings. I also take into account that she has no idea of the risks with her mental health that she would be taking by continuing with the pregnancy.” (Re AB before Lieven J [2019] EWCOP 26).

But Lieven J’s decision was reversed in Court of Appeal for not giving sufficient weight to the woman’s views: she”failed to take sufficient account of AB’s wishes and feelings in the ultimate balancing exercise (§55 (CoA)). The Court of Appeal went so far as to say that an incapacitous person’s wishes and feelings “can be determinative”:

“Part of the underlying ethos of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 is that those making decisions for people who may be lacking capacity must respect and maximise that person’s individuality and autonomy to the greatest possible extent. In order to achieve this aim, a person’s wishes and feelings not only require consideration, but can be determinative, even if they lack capacity.” (§71, Re AB (Termination of Pregnancy) [2019] EWCA Civ 1215)

The centrality of a pregnant woman’s own wishes and feelings was also underscored in a case heard some years ago by Sir James Munby in the Family Division rather than the Court of Protection (because the pregnant woman was a minor, aged only thirteen). He said that her wishes and feelings were a “vitally important factor” which he saw as “determinative”.

Only the most compelling arguments could possibly justify compelling a mother who wished to carry her child to term to submit to an unwanted termination. It would be unwise to be too prescriptive, for every case must be judged on its own unique facts, but I find it hard to conceive of any case where such a drastic form of order – such an immensely invasive procedure – could be appropriate in the case of a mother who does not want a termination, unless there was powerful evidence that allowing the pregnancy to continue would put the mother’s life or long-term health at very grave risk. Conversely, it would be a very strong thing indeed, if the mother wants a termination, to require her to continue with an unwanted pregnancy even though the conditions in section 1 of the 1967 Act are satisfied. (X (A Child) [2014] EWHC 1871)

At the time Mr Justice Munby made his decision, X was consistently expressing a wish for a termination and he ordered: “It shall be lawful, as being in X’s best interests, for a doctor treating her to carry out a termination in accordance with the criteria as set out in section 1 of the Abortion Act 1967 notwithstanding her incapacity to provide legal consent, subject to her being compliant and accepting of such medical procedure.”

This, then, is the legal context within which Hayden J confronted the question of NRs’ (incapacitous) wishes and feelings – seeming to want to give them great weight, even to treat them as determinative (as advised by the Official Solicitor), but without a clear sense of what they were, because she was so “riven” and held contradictory views pulling her in two different directions.

There have been similar decisions – leaving the choice to the incapacitous person – in relation to clinically assisted nutrition and hydration (CANH). Hayden J refers in the NR judgment to his own decision in Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership v WA & Anor (Rev 1) [2020] EWCOP 37

“I consider that every effort should be made, with the parents at the centre of the process, to persuade, cajole and encourage WA to accept nutrition and hydration. Attempts to deploy these techniques should be permitted with far greater persistence than would be considered appropriate in the case of a capacitous adult. I have no doubt that the attempts of persuasion will be delivered in the kindly and sensitive way that is most likely to persuade WA. I make no apologies for repeating that I consider WA has a great deal to offer the world as well as much to receive from it. No effort should be spared in encouraging him to choose life. This said, I have come to the clear view that when WA says no to CANH his refusal should be respected. No must mean no!” (Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership v WA & Anor (Rev 1) [2020] EWCOP 37)

Hayden J saw this as protecting WA’s autonomy “From this point on the decisions will ultimately be taken by WA with the advice and encouragement of his family and the clinicians, but no more than that”.

Best interests decisions for people with anorexia have sometimes followed a similar pattern, i.e. that clinicians can supply clinically assisted nutrition and hydration if the patient agrees to receive it, but not if she refuses it, after attempts to persuade her have failed (e.g. NHS Trust v L & Ors [2012] EWHC 2741 (COP))

However, these judgments are “best interests” decisions about the proposed treatment – and they permit “encouragement”, “advice”, “persuasion” in the direction of treatment.

The judgment in NR reads differently to me in that it seems not to make a best interests decision that treatment (termination) either is or is not in the protected party’s best interests – and although there is reference to “verbal encouragement and discussion” (§51) it was made clear in court that this is not to encourage NR to go through with a termination, but rather to encourage and support her considering her own wishes and feelings and making her own (incapacitous) choice. Hayden J says: “It is important that NR knows that I am respecting her rights as an autonomous adult woman to make this decision for herself, with the help of those she chooses to be advised by. I should also like Ms Crow to explain to NR that whatever decision she takes will have my fulsome support.”(§52)

I recognise that this decision is likely to be compliant (as most COP decisions are not) with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities because it affords NR the same right to decide for herself that a capacitous pregnant woman in her situation would have.

But that’s not usually the outcome of decisions made in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005, because once a person is deemed not to have “capacity” to make a decision for themselves, someone else (in COP cases, the judge) makes it for them. It might be the same decision as they would have made for themselves, and it might accord with their non-capacitous wishes and feelings. Or it might not. Either way, it’s not their decision to make, and their wishes and feelings do not determine that decision.

So, the surprising outcome in this case (NR) is that the judge says the choice is hers – and there’s to be no persuasion in the direction of a judicially-authorised “best interests” decision.

Each case in the Court of Protection depends on its own unique set of facts, of course, but I have yet to see any fully articulated argument as to why wishes and feelings should be determinative in pregnancy termination cases and not in cases of (say) court-authorised caesarean sections, or amputations, or other forms of medical treatment contrary to a person’s wishes and feelings.

I will watch developments with interest.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 500 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and tweets @KitzingerCelia