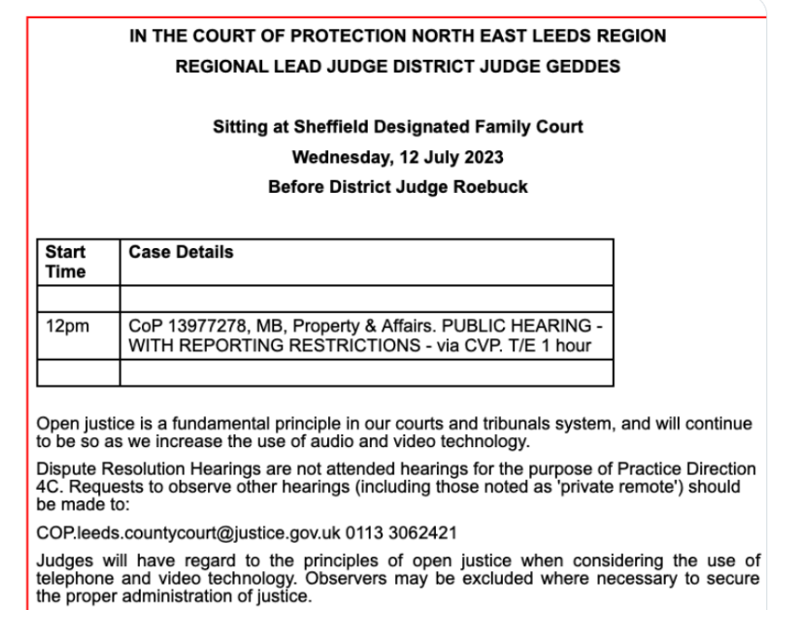

By Celia Kitzinger, 4 August 2023

Editorial note: For background information about this case click on the titles of these two blog posts: (1) : “Fact-finding hearing: Little short of outright war” (which has links to previous judgments) and (2) “A judicial embargo and our decision to postpone“. Note that we will now delay publication of our multi-authored blogs about the witness evidence that was given over the last two weeks (and the witness evidence yet to come) in October 2023, once all the witness evidence is complete.

The plan for the day (Monday 31st July 2023) was to hear the remainder of the father’s evidence, the first part having been heard on the Friday before. Then the court was supposed to move on to hear evidence from the mother and grandmother of the very vulnerable young woman (G) at the centre of the case.

But instead, due to sickness of a leading barrister, the hearing has now been adjourned (postponed) for nine weeks, until 6th and 9th October 2023.

A key reason for the nine-week delay is that Monday 31st July 2023 was the last day of the court year (which is organised into three terms – like the school or university year). The new court year starts on Monday 2ndOctober 2023.

The court has already heard the evidence from the witnesses put forward by the ICB (Integrated Care Board). Many care home staff gave evidence over seven days of the previous two weeks, expressing concerns about the behaviour of the family. The carers say the parents have been intimidating and rude to staff and that both parents and the grandmother have tampered with G’s medical equipment, including the equipment used to deliver oxygen, suction and feeding, placing her at risk of harm by interfering with her medical care.

We have heard the father deny this absolutely. He says that staff at the care home have placed his daughter at risk of harm. He says the care home is failing his daughter – they’ve not properly maintained her airway and lungs, her oxygen supply, her tracheostomy, or feeding tubes. He says they’ve failed to ensure she has adequate equipment which is properly set up, and that they’ve failed to maintain her personal hygiene, have used unsafe secondary ventilator settings, and failed to administer essential medications.

These are all very serious allegations – both those by the Care Home and ICB against the family, and those by the family against the Care Home.

The outcome of this hearing will be that the judge, Mr Justice Hayden, will decide the facts of the matter – and those “facts”, as determined by the judge in accordance with the civil standard of “balance of probability”, will have a profound impact on future decisions made for G: on where she lives, who cares for her, and the time she spends with the three closest members of her family. But as of today, those facts are not yet decided – because only some of the evidence has been heard (all the care home evidence, but relatively little from the family).

The father’s cross-examination should have continued today, to enable the court to establish the reliability or otherwise of his evidence. And we should have heard evidence from both G’s mother and from her paternal grandmother.

Instead, in the absence of Ms Nageena Khalique KC, lead barrister for the applicant ICB, the court spent the whole day working out first whether or not to adjourn (fairly quickly decided as ‘yes’) and then when the next hearing could be listed, and then what orders the judge should make in G’s best interests to cover the period between now and the resumption of the hearing. These interim orders turned out to be somewhat contentious and involved the Official Solicitor in obtaining instruction over the lunch break and providing a written submission for the afternoon session.

The hearing (morning)

By the time that “Court Rise!” sounded out, and the judge joined the video-platform at 10.22am on the morning of the hearing on Monday 31 July 2023, it was obvious there was a problem.

Ms Nageena Khalique KC, Leading Counsel for the applicant ICB (and the Care Home parent company), was not in her accustomed place in the front row to the right of our screens, where we’d seen her for the last eight days of this hearing. Instead, a much younger barrister, Olivia Kirkbride, took her place.

It turned out that Nageena Khalique is ill – she’s had three positive COVID-19 tests – and unable to come to court (even remotely) today.

As in any other occupation, there are different “grades” or “ranks” of barrister, and Nageena Khalique is one of the most senior. She was “called to the bar” – that means, she passed the vocational stage of training and qualified as a barrister – nearly thirty years ago, in 1994, so she’s very experienced. I often see her in Court of Protection hearings. She was recognised for her excellence in advocacy by being made a “silk” or “KC” in 2015.[1]

The barristers acting for the parents are also very well-known and experienced silks: Parishil Patel KC (called 1996, silk 2018) for the father; and Joseph O’Brien KC (called 1989, silk 2022) for the mother. So, too, is the barrister acting for the protected party (G) via her litigation friend the Official Solicitor, Sophia Roper KC (called 1990, silk 2022).

By comparison with these other barristers, all of whom are silks, and all of whom have been practising barristers for more than a quarter of a century, Olivia Kirkbride was “called” (i.e. qualified) in 2018, just five years ago. She has been in court throughout the hearing as “junior counsel” to provide support for Nageena Khalique as “Leading Counsel”. But now that her Leading Counsel was ill, it was quickly decided that the ICB/Care Home company would be placed at “a significant disadvantage” if the case were to proceed on that basis at this crucial stage of the hearing. This was accepted by all the parties, and by the judge (“I don’t think it would be fair to ask you to take up the brief at this stage”).

The problem then was how best to protect G and safeguard her best interests until the hearing could be finished – in the context of what the judge had already described as “little short of outright war” between the care home staff and the family.

On behalf of G, the Official Solicitor described this as “a significant source of anxiety … and almost despair: it’s a very troubling situation”.

Interim Orders

The judge raised the possibility of an order prohibiting all contact between G and her father, mother, and grandmother during the interim period before the next hearing. I was surprised by this. If, eventually, the facts are found to be that the care home is right and the family is putting G’s life at risk by tampering with equipment, then that decision would obviously protect G in the interim. But if, eventually, the facts are found to be that the family is right, and the care home is putting G’s life at risk through negligence or incompetence (and trying to scapegoat the family when errors occur), then that decision puts G at risk by denying her the protection afforded her by her family members, who – everyone accepts – are very knowledgeable and skilled in caring for her.

The audio was not good in the morning, but this is what I think I heard the judge and Official Solicitor (OS) say, as they reflected on how best to ensure G’s best interests, over the course of a nine-week break in the fact-finding hearing.

Judge: It’s about G’s welfare. I’m the judge responsible for that. What are the reasonable steps to take now? It’s difficult to answer that question when there is a fundamental dispute. Can I be satisfied that any contact at all [between G and her mother, father and grandmother] is safe? Would it be reasonable to allow unsupervised contact at this stage? What are the safeguarding obligations? And factored into that, the important evidence that G is, as I’ve hinted at a number of times, at the end stage of her life, however long that may be: that, I think, has to be factored into a person-focused, G-focused, arrangement that somehow balances both the identified risks and the welfare benefits. That’s what I have been struggling with. I’m not finding that easy.

OS: My Lord, it’s not easy for anyone. I’m aware of the points Your Lordship has made. I also have in mind the points all the other parties have raised that their evidence has not yet been adjudicated on. The outcome if either set of allegations is found is potentially very profound for G. It is not being suggested by anyone, including the Official Solicitor, that it is not safe for her to have unmonitored contact with her parents.

Judge: I am saying it.

OS: I recognise the court is entitled to make that suggestion, even if no party is advancing it. But the Official Solicitor is not advancing the position that G is at risk in the care of her parents or grandmother. The allegation from the ICB and [Care Home parent company] is that they say the reason why the family are tampering with equipment is to make the nursing home look incompetent. Yhe Official Solicitor is not making a submission as to whether that case was made out, but that is the most logical explanation.

Judge: It is not logical to make a submission that the loving parents will interfere with equipment and threaten the welfare of their child for that reason – but, if it is right, is it safe to assume the parents would confine that interference to in the care home and not outside the care home? It’s a risk dependent on location?

OS: Yes.

Judge: I have not come to any view at all. I have been grappling with this […] But confronted with this significant adjournment, the period of the next eight weeks is a particularly tense one for the family and for [the Care Home]. (inaudible) … serious allegations and counter allegations. The whole scenario is ripe for difficulties and there have been difficulties historically for years. These are very, very, very difficult issues to balance.

The judge sat silently for a while, apparently sunk in thought, hands clasped, the finger of one hand drumming against the knuckle of the other. He then raised another issue:

Judge: Has any thought been given as to whether [the Care Home] staff could be taken out of the picture altogether?

OS: I don’t have specific instructions as to whether it would be said by the Official Solicitor that there’s a prima facie case on the allegations so as not to (inaudible) I don’t think the Official Solicitor would say that the risk on the evidence so far would support cessation of contact altogether, or only supervised contact.

Judge: I am not necessarily with you on that.

OS: I appreciate that and will take instructions.

The sound then kept cutting out and everyone sounded intermittently as though they were under water. I did hear the judge say “I‘m going to have to have some analysis in writing about this” and make a reference to “tampering with life-sustaining treatment”.

Counsel for G’s father (Parishil Patel [PP]) got to his feet. The sound quality was really poor by now and kept cutting out. This is what I got down:

PP: I do want to say this one thing, My Lord. Your Lordship indicates what you’ve been thinking. There is detailed evidence about the standard of the care from both [G’s parents] and corroborated by the evidence of the care notes…[???] That is a matter Your Lordship hasn’t had a chance to [????] On the one hand, the family are saying not only do we not tamper with the equipment, but the care home is unsafe, and you haven’t made a finding. And they do say that, actually, that this is an unsafe place for G to be. If one is then going to come to a view about what is best for G before you’ve made any findings, then you need to bear in mind what family say [???? ]. We haven’t heard the evidence about what has been happening [????]. Hold the ring [????] …. In order to disturb what was Your Lordship’s view back in February, you would need a change in circumstances, particularly if you are going to change contact arrangements.

Judge: I understand all those points. [????] safeguarding [????] That creates a very clear tension.

By 12.34pm, the sound had gone completely. I watched Parishil Patel speaking, apparently forcefully, at one point beating the air with his hand. But I heard nothing of what he said. Both he and the judge looked somewhat tense. Shortly afterwards, the hearing ended for an extended lunch hour, during which I understood Sophia Roper was to seek instruction from the Official Solicitor as to what her proposals were as to what order could best promote G’s best interests during the following nine weeks.

Meanwhile I emailed the judge’s clerk letting her know that the sound quality had now deteriorated badly, in the hope that she might be able to fix it during the lunch hour. She did – and the sound quality was excellent in the afternoon.

The hearing (afternoon)

Each of the parties, except the grandmother (who is a litigant in person) got a ‘slot’ to present their position on the interim order. (I don’t know if the grandmother declined her slot, or if she was forgotten – as has sometimes been the case at various points in the hearing).

The ICB and Care Home

When the hearing resumed at 14:37, Olivia Kirkbride (for the ICB and the Care Home parent company) addressed the judge with some of the questions he’d raised beforehand (not all of which I’d heard). She said that that the Care Home wanted to maintain the placement for G, with safeguards in place to help them to deal with the situation. She said that staff had found giving evidence highly stressful and that there was a high degree of anxiety about having interactions with the family at the present time. But she did not propose further restrictions on family visits.

There had been internal discussions about handover (i.e. when the parents arrive at the care home to collect G to take her out into the community, and when they return her in the evening) – and they proposed that a designated member of staff from another unit, or even someone independent of the care home altogether, should be responsible for this. I think the judge had asked for a list of how many times the family had returned late for handover, in breach of the injunction, but this seems not to have been provided.

Counsel also reported that staff were stressed by the number of phone calls they were receiving from the family – including one apparently during the lunch break that very day from G’s father asking about her wellbeing. (I noticed he was shaking his head as if to indicate that this was not the case: he wrote something down, and passed the note forward to his legal team.)

Official Solicitor

The Official Solicitor had sent the judge a written submission, which (very helpfully) was also shared with me. As it turned out, the judge relied heavily on that submission in delivering his judgment (see below).

The Official Solicitor also did not propose restrictions on family visits beyond those already in place from the last hearing. The previous order from March sets out three visits a week, at prescribed times. When the family arrive at the care home there is a designated place for them to wait for G to be brought to them (“the Quiet Lounge”, just inside the front door). Using a member of staff from a different unit takes the pressure off staff and “may assist family as well because they are not dealing with anyone who is responsible for anything they’re unhappy about”. There seemed to be “some support” in the care home records for there be an excessive number of phone calls, which add to staff stress.

Counsel for G’s father

Counsel for G’s father, Parishil Patel, has been a consistently impressive advocate in this case, with a comprehensive grasp of the complex and exhaustive evidence before the court. He’s shown a gift for navigating the bundle and presenting the voluminous material before the court in straightforward terms. He’s also been persistent and meticulous in his cross-examination of witnesses and forthright in his defence of his client (intervening several times with “objection!” into other parties’ line of questioning). The judge recognised this at the very end of the hearing when he said “I do not believe anybody could have put their case with greater thoroughness and industry than you have on [G’s father’s] behalf”. This advocacy has sometimes involved, if not outright altercation, at least (what look to me like) tense interactions with the judge.

Picking up on the judicial concern with conflict between family and care home staff, Parishil Patel said, “it isn’t accepted that there is conflict at handovers” and pointed (again) to the fact that the family haven’t yet given evidence. There was then an exchange between Parishil Patel and the judge which seemed to hinge around a difference in nomenclature as to what does and doesn’t constitute “handover” – with the judge pointing to an occasion on which it is alleged that G’s mother “barged into the care home with the wheelchair” when returning G to the care home several hours late (due to transport problems): according to the night nurse, she was aggressive and shouting, and damaged the nurse’s foot with the wheelchair. (This was part of the evidence given the previous week.) The judge seemed to be taking “handover” to mean any occasion on which G was passed from the care of her family to the care home staff, or vice versa. Counsel seemed to be taking “handover” to mean the process that had been devised for checking the equipment in the course of that process. The exchange became somewhat testy.

Judge: Mr Patel, no doubt it’s my fault but I don’t think you’re following my concerns. The heat of litigation has been increased, not diminished, by the litigation of the last few weeks. I want to anticipate the sources of conflict rather than looking back – and make sure there is no room for ambiguity. I have no difficulty understanding why people come back late if they’re relying on public transport.

PP: That was the reason in every case.

Judge: I don’t need to rehearse the litigation.

PP: I know, but I‘m telling you.

The judge checked what arrangements the care home thought were (or should be) in place when the family returned late, and also asked about flexibility relating to visits on days other than the designated days when G was unwell, and visits from other family members (e.g. G’s sister).

Parishil Patel then spoke of the “absolute joy and love that there is between G and her family and the pleasure that she receives out of contact with her family”, which had already been conveyed by the father in his witness evidence. It seemed uncontested that the family have ways of communicating with G – and she with them – that are not available to the staff. He pointed out that if the judge were to think that G’s best interests were served by a reduction in her contact with her family, “that would mean she’d be left in company of staff, and you’ve heard that they don’t have or haven’t developed the level of interaction that her family have with her, so that would be a major disadvantage to G in that balancing exercise”.

Counsel for G’s mother

Counsel for G’s mother, Joseph O’Brien, said he wanted to “adopt and endorse everything Mr Patel has said in this case”. He pointed out “You’ve yet to hear from my client”. He raised the concern that there might be a risk that what had been said in court might “leave my client with the impression you’ve already formed an opinion”. Given that the other parties all thought contact between G and her family should continue over the course of the next nine weeks, he said that G’s mother “will be extremely grateful and her confidence restored” if this were to be the judge’s decision also.

And then the judge gave an ‘ex tempore’ judgment.

An interim ‘ex tempore’ judgment

An ‘ex tempore’ judgment is an oral judgment handed down orally during a hearing – often without a break in the hearing, or sometimes after a short break (15 minutes to an hour in my experience) to allow the judge to gather their thoughts. The term ‘ex tempore’ is Latin for “out of the moment”. The other way a judge delivers a judgment is to “reserve” it – meaning they hand it down in writing later – usually days, weeks or even months after the hearing.

On this occasion, Mr Justice Hayden’s ex tempore judgment was delivered without a break in the proceedings. He asked the junior counsel to take a note of the judgment and to send him an agreed transcript of it, which he will then have the opportunity to “perfect”.

“Perfecting” a judgment begins with filling in any missing words or phrases that counsel were unable to hear, and correcting any mistakes counsel may have made in rendering the judge’s words in print. It includes dealing with any problems in grammar and punctuation, and any lack of clarity in the way the judge has expressed their reasoning. The parties also have a duty to correct any errors the judge has made – although this is not an opportunity to reargue the case or try to persuade the judge to change their mind. The judge can make these corrections, alter the wording of the judgment, and add in new sentences with additional reasoning explaining the decision reached. The judge has discretion to change – even reverse – their decision at any time before their order is sealed by the court (although this is very rare)[2].

So, what follows is a long way from having the status of an ‘approved judgment’ in the same sense that the published judgments on BAILLI and the National Archives do, but it is (to the best of my ability) an accurate record of what Hayden J said In judgment in court. As barrister and blogger Lucy Reed says: “Use of the phrase ‘transcript of judgment’ to describe an approved judgment probably isn’t helpful because it doesn’t make clear this distinction between a transcript (the raw material) and the judgment (the finished product)’.[3] What I’ve captured below is the raw material. I don’t know if there will be an approved published judgment – and I haven’t seen the order.

Mr Justice Hayden’s ex tempore judgment

“Allegations brought by the ICB, the applicants in this case, and the countervailing allegations brought by the family, have properly in my judgment been described as being of the utmost gravity and which if found, in either case, have far-reaching implications for G’s welfare. G is the 28-year-old young woman at the heart of these proceedings, whose welfare responsibility this court is charged with. Because of the nature of the allegations, the Court of Protection took what is the very rare – and I hope will continue to be very rare – (though not unprecedented) measure of convening a fact-finding hearing. As it transpired, the time estimates of the hearing had not proved to be accurate. I state that as fact and it is not to be taken by anyone as a criticism. Only by sitting long and quite demanding days has it been possible to keep the case, broadly speaking, on track.

Unfortunately, counsel has been taken sick with covid over the weekend and is not in a position to proceed. That is a reminder that we are still living with this insidious virus. Given we’ve reached a point where family were in process of giving evidence, I have taken the view that it would be unfair to burden Ms Kirkbride, junior counsel for the ICB, with the responsibility for taking up the reins of cross-examination at this stage. Inevitably, therefore, the case has had to be adjourned. In the finest tradition of the Court of Protection Bar, both

Mr O’Brien KC and Mr Patel KC have agreed that such a course is necessary.

On the very last day of the Trinity term, this presents considerable problems. Though I should have preferred that the conclusion of the case be heard in my vacation slot at the end of August, I recognise that the logistics of that are not in our favour, so I have concluded that the case should recontinue at the earliest possible date at the commencement of the new term, and it’s been possible to fix the case for 6th and 9th October.

Axiomatically, that poses a real challenge for interim arrangements for G’s contact with her family. There are, as I see it, two central issues here. The family assert that G is essentially at risk in the care of [the Care Home], whose standard of care for her they contend falls below that which her welfare needs necessitate and which she is entitled to expect. Explicitly, they contend that she is unsafe. And it is not appropriate at this stage to burden this short extempore judgment with the more graphic adjectives which have been employed [????][4].

The ICB countervailingly assert that the family, led by the father, have mounted an insidious campaign to destabilise the placement and to undermine the staff – which it is contended involves essentially abusive behaviour to staff, and a level of interference with G’s care that jeopardises her welfare and safety.

The level of conflict at this hearing has been almost palpably tense and distressing to watch, not least for the nursing and care staff. The presentation of each of the witnesses from [the Care Home], whatever its genesis, has been profoundly troubling.

Irrespective of what my ultimate conclusions might be on the evidence – evidence which I emphasise remains incomplete – I have formed the view that the placement at [the Care Home] for whatever reason is manifestly hanging by a thread. Nobody sitting in this court for the last few weeks or watching it remotely, could come to any other conclusion.

It is contracted as an intensive placement for a young woman with complex needs. If it is not already obvious from the evidence that the court has heard [????], it would be immensely difficult to find an alternative establishment – a difficulty which will no doubt have been exacerbated by the history of this case, whatever my ultimate conclusions on the facts might be.

The risks to G’s welfare which have in the past few months under the regime that this court ordered been manageable, have, in my assessment increased – not diminished – by this corrosive, highly litigious, and profoundly troubling period that is inevitably the consequence of litigation of this complexion. In this jurisdiction in particular, which ordinarily focuses on questions of capacity and best interests [????} however sensitive and complex the issues might be, questions of credibility arise only very rarely. The relationship between staff and family was described as being “at rock bottom”. On that, if on nothing else, I suspect both sides would agree.

An important aspect of the ICB’s case is that family members, most particularly the father and paternal grandmother, have tampered with the machinery upon which G relies to breathe. The motive identified for such otherwise incomprehensible behaviour was it had been done to manufacture evidence of the incompetence of [the Care Home] staff. Ultimately, I will have to evaluate the cogency of evidence in support of those allegations, but if they are found to be made out, they reveal a disturbing, dangerous, and in my judgment unpredictable mindset.

During the last 2 weeks, in the course of this hearing, the parents have had no contact with G – and faced with a considerable period of adjournment, it is the responsibility of the court to consider how the risk of contact between G and her family can be managed in the interim, given the increase in temperature of the conflict which these proceedings have, in my judgment, generated.

Indeed, I have asked myself as I am bound to do considering the nature of the allegations whether it would be right to reintroduce contact at all. Notwithstanding the general consensus that G enjoys time with her parents, and I would add gains a reassurance from their presence and touch which no one else can deliver, the Official Solicitor believes, and I agree, that at this point, the preservation of the stability of the placement remains the priority – the apex of G’s identifiable needs.

Unless or until any of the criticisms levelled by the family is established, [????} in the interim, the placement has been observed by independent professionals, e.g. Dr A who is satisfied that G is not [at risk?] in her placement. And I do not need to be reminded that that evidence is, like so much else in this case, challenged.

I have had to turn to the Official Solicitor to assist in evaluating the way forward in the interim that keeps G’s welfare needs, her best interests, unwaveringly in focus. That is not concerned with ‘holding the ring’, nor should the contact arrangements put in place be driven by the general exigencies of the litigation. It is always G’s evolving needs that have to be (as I have said) the unflinching focus.

Ms Roper on my request, along with her junior, Mr Harrison, have been able to put a document together on behalf of the Official Solicitor, G’s litigation friend, mapping out the Official Solicitor’s analysis how the process I have identified can best be [????] over the course of the next two months.

Ms Roper and Mr Harrison emphasise the following.

Firstly, [the Care Home] has not alleged that any family member has tampered with G’s equipment while she has been out with them, at any point since she was discharged there on 18 August 2022.

Second, there are no allegations of any tampering with G’s equipment at all since the current contact regime began, following G’s discharge from A Hospital on 7 March.

Third, the checklists completed by both sides on handover since 7 March ensure that there is an effective rigorous process of professional oversight and complete accountability as to the condition of G’s equipment – both when she leaves [the Care Home], and when she returns.

These key facts, it is contended, point to a manageable risk.

I have had to go further and ask myself whether those protective factors are likely to endure at this particularly tense period in the context of allegations which I have already emphasised [???] reveal an unpredictable mindset.

To fortify the present arrangements, the Official Solicitor contends that direction can and should be given for weekly disclosure of all the records of [the Care Home] including correspondence, and secondly, some provision made for this case to gain urgent return to court in the event that quote “any tampering is suspected”. For my part, I would modify that last phrase to state ”reasonably to believe” that tampering has occurred.

That involves one aspect of the court’s concern. The second is the sustainability of the placement which, I repeat, I have characterised as hanging by a thread, with staff morale at rock bottom. Ms Roper addresses that in this way.

Firstly, she points out that of those witnesses who were asked about imposition of a restrictive regime of contact post-7 March 2023, their general response was to the effect that it has proved to be manageable albeit that that has not had much by way of positive impact upon the morale of the staff.

The return of G from contact – and the potential flashpoint of what I have called ‘handover – has the Official Solicitor asserts been ameliorated by the present regime, as I understand it, of deploying a member of staff from a different unit within [the Care Home] to facilitate that process. It is plainly important that that member of staff is provided with a written handover guide setting out any updates for the family and that the checklist is completed with the family in attendance.

Thirdly, the effect of the current regime is there is no face-to-face contact between the family and those who are immediately responsible for G’s day-to-day care at [the Care Home]. That involves a number of those nurses and carers who have given evidence before me. That separation between the family and the nurses and carers intimately involved with G’s care on a day-to-day-basis, is manifestly undesirable. It serves if not to block but to my mind inevitably impede a channel of communication which ought to be regarded as intrinsic to her wellbeing. The fact that it is advanced by the Official Solicitor on G’s behalf as an important protective measure to her wellbeing (i.e. that there be no such contact) is an indicator of how far this case has drifted from the ordinary safe moorings of a collaborative relationship between family and carers.

Fourthly, the Official Solicitor has been told – and Ms Roper says this is supported by some of the records – that the outstanding pressure point is the number of calls being received from the family. Mr Patel tells me they are not as numerous as is being presented, or alternatively that they are only made when strictly necessary. Ms Kirkbride sets the scene for the issue by telling me that there was a phone call this morning, notwithstanding the case (???). The Official Solicitor has concluded that a satisfactory channel of communication could be devised by the allocation of a designated senior member of staff who would call a family member with a general update on a daily basis on those days when the family aren’t visiting. The Official Solicitor recognises that while that may have benefit in reducing the potential for conflict, it cannot be set in stone, because of the nature of G’s condition, and the ever-present potential for her to become unwell. Any such arrangement, it requires to be stated explicitly, should not exclude the professional – and I would add moral – obligation to contact the family as expeditiously as possible if G were to become ill outside of the suggested arrangements.

Mr [Care Home Manager] indicated during the course of his evidence in the witness box, that he was willing to offer the family greater flexibility of contact, particularly if a day was missed. {The Care Home ]has been able to demonstrate flexibility recently when they were able to negotiate G’s attendance at her grandmother’s marriage to Mr E. In a case without very much sunshine, that was at least a shaft of it – and it encourages me to think potential for flexibility in contact remains if a day is lost. The principle of substituting a day will of course [be dictated by P’s needs?].

There has been some suggestion, which I have not explored, of the possibility of a vehicle being made available to the family to enable them better to withstand the unpredictability of the public transport provision around [the Care Home] and ensure a greater degree of consistency regarding G’s return. Here, too, there is some tentative cause for optimism. The time of return is now prescribed by injunction, the force of which appears to have been met.

Whilst I have found these interim arrangements to impose some really serious issues at this stage, and whilst I can see that they might very well be replete with potential for conflict, I am satisfied that the protective architecture that the Official Solicitor has suggested is sufficient to enable me to evaluate the risk as a manageable one, given that in taking it, I will be able to maintain G’s contact with her family, which she not only derives pleasure from but which requires to be recognised for what it is – her right, which should only be displaced where there are cogent reasons to do so. Ultimately, I am satisfied that those reasons do not exist and that basis [????] the proposals advanced by the Official Solicitor.

Parties will know that I have not found this an easy decision. Evaluating the [????] is difficult and many would err on the protectionist side. In recognition of the importance of the relationship between G and her family and the general canvas of her circumstances I believe this is a manageable risk that ought to be taken.

It does follow, however, that if something goes wrong between now and 6 October, that delicately balanced risk might easily be displaced and require revisiting.

I profoundly hope that the contact between now and 6th October will provide me with the opportunity to read something joyous about G’s life. But far more than that, I hope for her that what will be in effect the remainder of this rather soggy summer will nonetheless be a positive and happy experience for her.

****

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 460 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and tweets @KitzingerCelia

[1] The letters “KC” after a lawyer’s name stand for “Kings Counsel” (previously QC for Queen’s Counsel). Lawyers who are KCs are often referred to as “silks”, which comes from the uniform upgrade they get – from the plain black gown most barristers wear in court to a shiny silk one (hence “taking silk” as a description for this promotion). The emergence of the Queen’s Counsel during the late 16th and early 17th century was during a time when silk was a rare and expensive commodity. Later, King James I was particularly fond of it and keen to exploit its production throughout the colonies. The king’s preferred barristers would be dressed in his favoured fabric. Check out “What is a silk” and “Taking silk” – according to the which, “adding those precious two initials [KC] to your title gives you status and privilege that most in the legal profession will only dream of”.

[2] See: §16-§46 In the Matter of L and B (Children) [2013] UKSC 8 for some legal history concerning altering judgments (thank you to Daniel Cloake aka @MouseInTheCourt for bringing this to my attention). See also: Altering draft judgments; “When a judge changes their mind”; and the very useful blog post about what’s in a recording, what’s in a transcript, and what’s in a judgment and why, by Lucy Reed in Pink Tape here: “What’s in a judgment anyway?”

[3] I’m grateful to Claire Martin who was also in this hearing and made a detailed note of this judgment. I checked my transcript against hers, which enabled me to add in a few missing words, and to gain confidence that what I had written down was largely correct. Missing words in my version were also very frequently missing words in her version though. Hayden J can be hard to hear in court (both in person and remotely).

[4] [????] indicates places where the word (or words) spoken were inaudible, both to Claire and to me.