By Celia Kitzinger, 25th October 2021

A woman in her 50s (Miss T) has severe cataracts in both eyes and is “struggling” with her vision. But she’s refusing cataract surgery.

She’s been in hospital for more than a year, admitted under s.3 of the Mental Health Act 1983 following a relapse in her long-standing mental health problems. She’s diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

She usually lives in low-level supported accommodation with a floating package of support of between three and five hours a week (although she “was not cooperative with it”). The intention initially was to discharge her home. That’s also what she wants for herself.

Until a few years ago, she had a significant amount of independence: she was in a romantic relationship, working in a charity shop, and doing the gardening for the supported living placement.

Without cataract surgery, it is “very unlikely” that she could return home, due to the level of support and supervision she would need and her reluctance to accept this. Her social worker, occupational therapist and the care provider have all assessed her as not being safe to return home unless her vision improves. She’s historically refused to cooperate with care, and has rejected offers of care packages in the past, so simply commissioning a care agency to provide more support is unlikely to work.

Although she denies having any problems with her eyesight, staff have observed her walking into pillars and walls. There was an occasion when she fell when trying to sit on a sofa due to her poor eyesight, and she’s had difficulty pouring tea. Left untreated, her eyesight will worsen and she’ll go blind.

The medical situation has been explained to her many times, and she “maintains a strong objection to undergoing any treatment for her bilateral cataracts”. When the topic is mentioned ,she often says “No thank you” or simply leaves the room. At times she has said she doesn’t “feel ready”, or that her vision will improve spontaneously, or “I don’t mind going blind”, or that she is refusing because she doesn’t want a blood transfusion (it has been explained to her that blood transfusions are not part of cataract surgery). The Trusts’ view is that Miss T is “overwhelmed by her fears about the surgery as a result of her mental illness”. According to her sister, Miss T has always taken a long time to come round to anything new: she is “very fearful and extremely resistant to the unknown”.

So, the court was faced with a person with two incompatible wishes: on the one hand, a wish to return to her home of twenty years and live relatively independently, and on the other, a “consistent and fixed” view that she does not want cataract surgery.

As the NHS Trusts put it: “The two wishes (not to have the surgery and to return home) are mutually exclusive. It is one or the other”.

The hearing

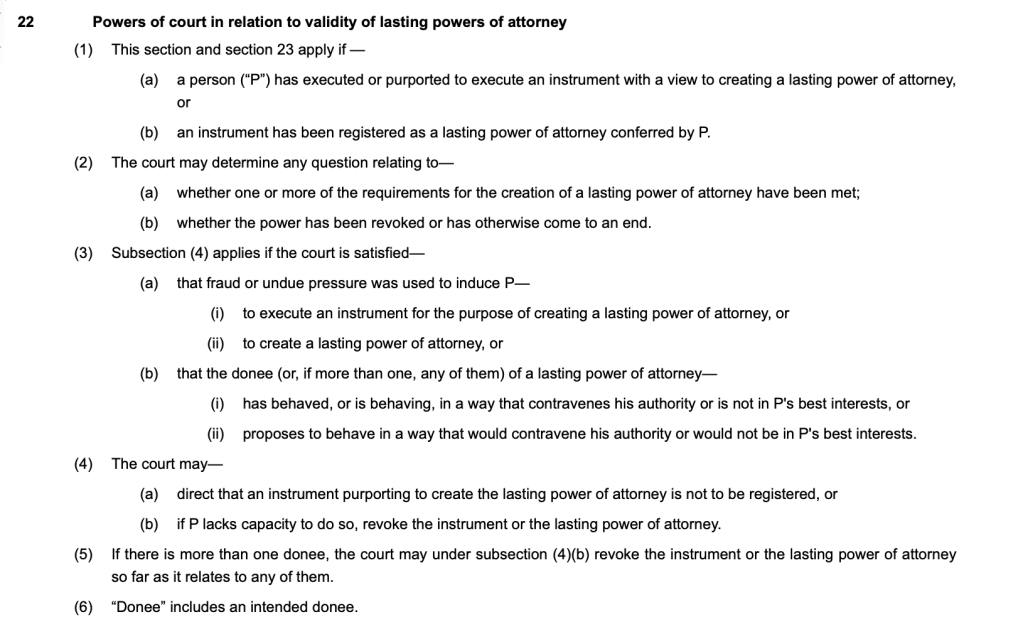

The hearing before Mrs Justice Knowles (COP 13790122, 9th August 2021) arose from an application by two NHS Trusts: the one currently treating Miss T under the Mental Health Act 1983, and the hospital trust seeking to carry out the surgery. They were applying (jointly) for declarations that

- Miss T lacks capacity to conduct the litigation or to make decisions about cataract surgery; and

- that it’s in her best interests to have the surgery – using physical restraint to enable this, if necessary.

At the beginning of the hearing the judge clarified the position on the transparency order (“no identification of the person with whose welfare we are concerned, or anybody belonging to her family, or where they live or where she’s cared for – and the same for her family members”) and checked who was in court: counsel, instructing solicitors, the two witnesses (Miss T’s treating psychiatrist and the ophthalmic surgeon) and Miss T’s sister. Miss T was not present in court and I later learnt from the position statements that she’d said she did not want to be involved in the hearing.

The judge then checked her understanding of the position taken by the Official Solicitor (Nageena Khalique QC) who was responsible for representing Miss T’s best interests.

Judge: The Official Solicitor’s position is about capacity? That P may be capacitous

and, to put it bluntly, making an unwise decision?

OS: Yes – except we also have a question about doing surgery on two eyes at the

same time.

Judge: The surgeon deals with that in his statement.

OS: He says it’s for expediency. We just want to be clear about the benefit of this

as against having one done, and then Miss T can recognise the benefit before

the next one. And, also, to know there isn’t a high risk of damage if they’re done

at the same time. This operation isn’t usually done on both eyes at the same time.

There was then a very useful summary of the case “for the benefit of observers” from Rachel Sullivan (counsel for the Trusts, instructed by Olivia Gittins). She ended by saying that Miss T’s cataract surgery had been provisionally booked for 1.30pm on the afternoon of the following day, pending the outcome of this hearing, and that there was “concern that if the operation doesn’t go ahead in that slot, there may be some delay before it can be rescheduled”. (My understanding was that the delay is in part due to Miss T refusing to have the covid swab, necessitating special arrangements for surgery.)

We then heard from the witnesses, and from Miss T’s sister.

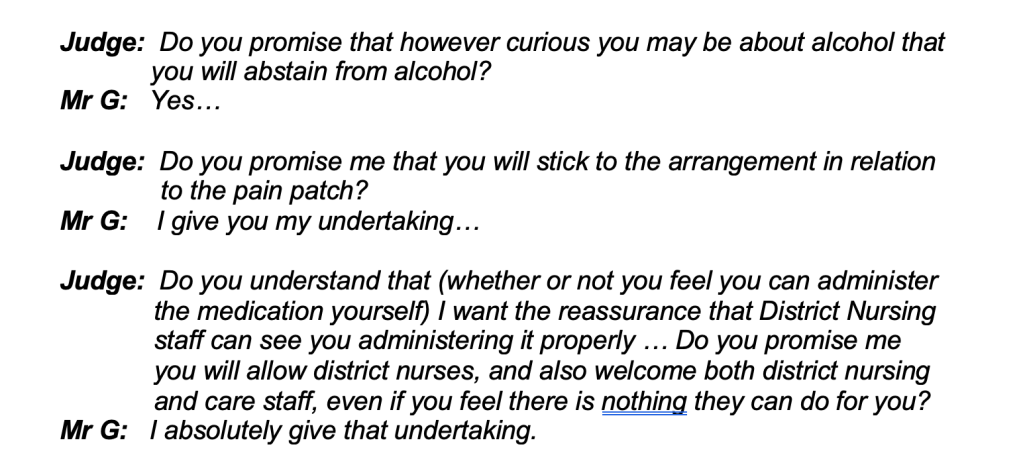

Throughout the hearing, the judge intervened quite frequently to clarify certain points or to comment on issues that had been raised. Having watched more than 200 Court of Protection hearings so far, I am beginning to get a sense of the different ‘style’ of the various judges. Compared with others, Mrs Justice Knowles seems to me to exercise more ‘control’ over what happens in her courtroom (in a relaxed, confident and engaged way) and to be more actively engaged in eliciting the information and the evidence she needs to make the decision before her (where others seem to be passively waiting for counsel to deliver). She is far more interventionist than some judges – as she herself suspects:

“What those who appear in front of me think is anyone’s guess though I suspect they might say that I interrupt counsel’s submissions too readily with questions and suggestions. That’s a style honed by the inquisitorial function of tribunals which I’m not sure I’m prepared to surrender readily.” (Mrs Justice Knowles)

The judge’s ‘style’ may be apparent from this report.

Witness 1: Consultant Psychiatrist and Responsible Clinician

The consultant psychiatrist responsible for Miss T’s psychiatric care gave a detailed and comprehensive account of what she knew of her as a person. She described her as “a very dignified and private woman” who is “very frightened about something”, but she has never been able to discover the source of her fears: “that part of her experience is quite closed off to me”.

The psychiatrist described Miss T’s behaviour at home before her most recent admission: “She barricades herself in her home, she stockpiles dry goods like there’s an apocalypse coming, and she won’t let people into the house – even when the plumbing breaks, she won’t let the plumber in”. She has no doubt that Miss T wants to return home: “this place is where she wants to live”.

She explained that she’d initially observed Miss T’s problems with her vision – “she had difficulty reaching for her tablets, or finding the door” – and had encouraged her to get it checked out:

“I offered to give her an examination and she didn’t want one. I tried male doctors, female doctors, senior ones, junior ones; I thought maybe it would feel more normal to go to her GP or to the opticians, so I’d set up appointments and then she wouldn’t go. Many months later she did go and get her eyes assessed, and I was delighted to find out it was cataracts, because they’re so easily fixed.”

She described how Miss T is now:

“She walks in small steps and bumps into pillars and posts. But she gets angry if you try to guide her. I keep up a stream of speech when I’m walking with her so she can hear where I am, but I occasionally say ‘oh, mind the pillar!’ and she finds that very upsetting. She mostly doesn’t acknowledge there’s anything wrong with her vision. Sometimes she says she expects her vision to get better.”

Asked whether any other members of the treating team are able to elicit more information from Miss T, she mentioned the Occupational Therapist (OT) who “has a really nice relationship with her”.

“The OT tried to talk to her about alternatives to surgery – including aids for partially-sighted individuals. But even when Miss T is well, she’s guarded and suspicious. And I think the OT doesn’t have expertise in supporting partially sighted people and wanted to involve another member of the team, but Miss T would have none of it.”

The judge intervened at this point to say “We’re running out of focus in terms of your evidence” and asked the witness to provide some information about “the current state of this lady’s mental health right now”.

“I think she’s currently at her best, but not a totally well person”, said the psychiatrist.

The judge then pursued the question (raised as an issue by the OS) as to whether Miss T has capacity to make her own decision about whether or not to have cataract surgery:

Judge: Your concern is that her capacity to understand the issues related to cataract surgery is affected by a degree of mental ill health which is not treatable by the medication you’re providing?

Psychiatrist: Correct.

Cross-questioned by counsel for Miss T (via her litigation friend the Official Solicitor), the psychiatrist reiterated her view that Miss T does not understand the information she’s been given about surgery for cataracts (“and what she does understand she doesn’t believe”).

She couldn’t think of any other drug that could help with Miss T’s psychiatric symptoms. She also described previous occasions on which Miss T had been chemically restrained in order that staff could administer psychiatric medication.

Counsel for Miss T: Have I understood you correctly? Despite having had lorazepam intramuscularly against her will she has not fallen out – for want of a better expression – with her therapeutic team?

Psychiatrist: Yes.

A little later the judge took over again:

Judge: You told me at the start of your evidence that a precipitating event for this latest episode of mental ill health was a perceived threat to the security of her accommodation and you described her independence, and that the flat was something that was very dear to her. It sounds as though her return to that place remains a goal that she wants to pursue. Do you think she has any understanding that her eyesight, if untreated, will absolutely preclude that from happening?

The psychiatrist thought Miss T did not understand that she’d not be able to return home if she didn’t have surgery. She’d earlier described how, when she’d raised this concern, Miss T had brushed it off by saying, “I’ll be fine! I know my home!”

The judge also asked whether she thought Miss T had capacity to conduct litigation.

Psychiatrist: No. I’ve tried to explain to her that a judge would make a decision in a court, and a solicitor would meet with her and represent her in a court. She said that was not acceptable and couldn’t happen. I don’t think she can understand, retain or weigh information in relation to this procedure.

Finally, the judge referred to “one final little T I need to cross” – which turned out to be getting the witness to adopt her statement (i.e. the bit that usually happens after a witness is sworn in when they’re asked whether a written statement provided in advance is their statement, whether the signature on it is their signature, and whether it is true to the best of their knowledge and belief). Somehow that had been omitted earlier (“you weren’t formally asked to do that”).

Witness 2: Ophthalmic surgeon

The surgeon was sworn in (and asked to adopt his statement) and then questioned about the proposed surgery.

He said that bilateral cataract surgery (i.e., operating on both eyes at the same time) is “not uncommon”, that he’d done it before, and that it would be preferable to “putting Miss T through this process twice”. Surgery is the only chance of restoring her sight.

He was questioned about the risks involved. There’s a 1% risk of the surgery making her vision worse than it already is and a risk of total visual loss that is less than 0.1%. General anaesthetic would be necessary because it’s a fine-touch procedure where millimetres make a difference, and if Miss T were not to cooperate during the procedure itself, the results could be catastrophic.

Under cross-examination there was some discussion of the post-operative regime, given that Miss T is likely to refuse eye drops, which are designed to reduce inflammation and provide symptomatic relief for the “scratchy sensation” she’s likely to feel after surgery. The proposed solution was injection of antibiotics directly into the eye as part of the surgical procedure: “it sounds horrendous”, said counsel for Miss T, looking rather squeamish, “but it’s obviously necessary”.

Sister’s views

Although this wasn’t (I think) formal evidence, the judge invited Miss T’s younger sister to “unmute if you want to say anything to me now”. Miss T’s sister spoke articulately, passionately and unequivocally in favour of surgery for Miss T – and she did so not only on her own behalf but as a representative of other members of the family.

“We want the best for our sister who’s had a pretty tragic life and whose life has actively deteriorated in the last 15 years or so. For her to go blind when we’re in a position to restore sight to her just seems absolute madness. My strong appeal – my sister’s and my strong appeal – We come from a medical background, my father had cataract operations, we’ve asked family members who’ve had cataract surgery to talk to her and we don’t understand why she doesn’t run towards this very simple, very effective operation with open arms. It’s part of her mental state. I’ve tried very gently. My main objective is to preserve the relationship. Mostly with me she never discounts surgery, never tells me directly that she refuses to have it. Invariably to me she says, “I’m on the waiting list, let’s see”. She can’t make the decision. She lives in the present. She won’t make a decision about anything that is going to put her in a state that is going to be different from now. Having her eyesight restored would be a transformational event in her life. It would provide more opportunities to enrich her life – like knitting which she can’t do now, no matter what size needles I buy, and simple pleasures like gardening. I can’t see any reason why this opportunity should be withheld from her, even though – perversely – she’s not agreeing to it. It’s her mental state, the paranoia, the swirling around in her head. The way my sister thinks, it’s such a sad and tragic state of affairs. From the bottom of my heart, I would make the appeal to you that she has this surgery. I really would.”

Closing Submissions

The closing position of the Trusts remained that Miss T lacks capacity to make her own decision about surgery. Counsel referred to “at least 26 occasions since November 2020 in which the need for surgery has been discussed with Miss T”.

“They reveal a very mixed pattern of engagement and response: in almost all cases she either refuses to accept she has a problem with her eyes, or that she needs surgery. She minimises the effect of not having surgery, for example on returning home. The reality of the situation is that this is a lady with a lengthy and serious psychiatric history – and, as the psychiatrist has explained, even medicated as best she can be and with her mental health as good as it gets, it’s impossible to be sure that her paranoid thinking is not interfering with her decision-making about surgery. Something is colouring her refusal, which is marked by extreme agitation and distress. […] We invite you to find that the presumption of capacity is displaced and that it’s palpably in Miss T’s interests for surgery to go ahead.” (Counsel for the Trusts)

The closing position of the Official Solicitor was also that Miss T lacks capacity and that surgery should go ahead in Miss T’s best interests.

“The psychiatrist’s evidence suggests that Miss T has an inability to make the relevant decision because of her being unable to understand the salient facts in relation to the procedure. The reason for her not being able to understand is her mental disorder, which became extremely clear during the course of the psychiatric evidence and was emphasised by her sister who paints a very vivid picture of Miss T’s health and approach generally to new scenarios and the incredible difficulty Miss T has with engaging in discussions necessary to make certain decisions. In my position statement I refer, in paragraph 31, to the case of PCT – an old case but a useful one – to address the question of whether Miss T is refusing to engage in the decision-making process. She is obviously refusing to engage for example with the fact that if her eyesight isn’t treated, that will have a knock-on effect on whether she can go home. So, she lacks capacity on this matter and the jurisdiction of this court is available. The next step is to consider her best interests. Not going blind is a consideration of magnetic importance. The Official Solicitor acknowledges that Miss T has expressed an almost consistent wish that she doesn’t want the procedure done, but wishes are not determinative.” (Counsel for the Official Solicitor)

The judge intervened at this point and said:

“In respect of her wishes and feelings, she has two utterly contradictory wishes and feelings. One is not to have the procedure, and she’s pretty consistent on that. The second is an extremely strong wish to return home. Those two wishes and feelings cannot be reconciled, because she cannot return home unless she has the surgery she is so opposed to. That must affect the weight I give to the wish and feeling about not having the operation.”

Counsel agreed, adding that the Official Solicitor’s concern about having surgery on both eyes simultaneously had been allayed by the ophthalmologist.

The OS position now was: “We say the benefits are hugely significant and easily outweigh the risks, and we support the application and order that the Trusts seek.”

Judgment

Mrs Justice Knowles took a 20-minute break to prepare an ex tempore judgment.

Returning to court, she summarised the evidence and found that this was “not a case where a capacitous individual is making an unwise decision”. Having heard the evidence, she was “satisfied that Miss T lacks capacity to conduct this litigation and to make a decision about cataract surgery”.

In terms of Miss T’s best interests, she noted Miss T’s “fixed view against surgery”, pointing out that “it is a strong feeling which is mutually exclusive with her strong desire to return to her home”. As a consequence, “the weight I give to her strong desire not to undergo surgery is outweighed by the benefits of surgery and living independently”.

The judge concluded that it was in Miss T’s best interest to undergo bilateral surgery, with restraint if needed, as a last resort.

She ended the hearing by saying she wanted to “thank everyone who has worked so hard to try to ensure that Miss T is able to participate in this very difficult decision”, including especially Miss T’s sister for “outlining the very real difficulties that Miss T faces and the need for her to have this procedure to have an improved quality of life”.

The judge indicated that the judgment would be published in due course.

Was it the right decision?

I’ve watched lots of hearings in which judges have made decisions about whether or not to authorise medical interventions for people who don’t want them – including (for people with schizophrenia) HIV medication, amputation for a gangrenous leg (and also here and here), endoscopic dilatation for a benign peptic oesophageal stricture and kidney dialysis. Sometimes judges have authorised these interventions and sometimes not: each case is different.

It can feel wrong to force someone to have medical treatment they say they don’t want.

It can also feel wrong to acquiesce to someone’s (non-capacitous) wishes, knowing that they will suffer and/or die as a result.

Undoubtedly the easiest solution for the medical team caring for Miss T would have been to accept Miss T’s refusal of surgery – either presuming that she had capacity to refuse, or on best interests grounds (taking full account of her strong views on the matter, and the likelihood that restraint would be needed).

But accepting Miss T’s stated preference not to have surgery would be likely to result in poorer physical health and reduced life-expectancy for her. She’d be another number in the statistics for poor health and excess mortality rates among people with mental illness.

Like people with learning disabilities, people with severe and enduring mental illness are at greater risk of poor physical health and reduced life expectancy compared to the general population[1]. Excess premature mortality rates are more than 3 times higher amongst people with mental illness in England compared to the general population[2].

Acquiescence to refusals of medical treatment by people with serious mental illnesses[3] contributes to these health inequalities.

For Miss T, the authorisation of cataract surgery seemed (to me) the right thing to do.

I learnt later that surgery had been successful in restoring her sight, that restraint had not been required, and that she was happy to be able to see again.

Without input from Miss T’s sister who strongly advocated for surgery, and without the endorsement of the court, it’s possible the health care team might have felt it kinder to accept Miss T’s refusal of treatment – and there would have been no ‘happy ending’.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She tweets @KitzingerCelia

Photo by Brands&People on Unsplash

[1] These reports from Public Health England document a range of reasons for health inequalities for people with serious mental illness: they include wider social factors such as unemployment and poverty, increased behaviours that pose a risk to health such as smoking and poor diet, lack of support to access care and support, stigma, discrimination, isolation and exclusion preventing people from seeking help and “diagnostic overshadowing” (misattribution of physical health symptoms to part of an existing mental health diagnosis, rather than a genuine physical health problem requiring treatment).

[2] NHS England guidance, Improving physical healthcare for people living with severe mental illness in primary care sets out what good quality physical healthcare provision in primary care must include. A Kings Fund report Bringing together physical and mental health sets out what an integrated approach to physical and mental health would look like for people with mental illness.

[3] Van Staden CW, Kruger C. Incapacity to give informed consent owing to mental disorder. J Med Ethics. 2003;29(1):41–43. doi:10.1136/jme.29.1.41; Kontos N, Freudenreich O, Querques J. “Poor insight”: a capacity perspective on treatment refusal in serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(11):1254–1256. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500542