By Gaby Parker, 29th June 2021

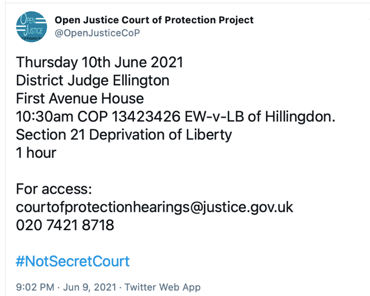

On 23rd June 2021 I observed a hearing (via MS Teams) before Mr Justice Hayden in the Court of Protection: COP 1354439T Re. PH.

The case was about finding a suitable placement for P who remains in hospital although he is fit for discharge and has been for a long time.

The hearing turned out to be a continuation of a hearing from two days earlier (which I had not attended). It was clear that issues in P’s care had been before the court on a number of previous occasions, with attempts to find a suitable placement for P first coming before Mr Justice Hayden in August 2020.

Counsel for P (via the Official Solicitor) was Ian Brownhill, whilst counsel on behalf of the Hospital Board was Roger Hillman. Hayden J very helpfully invited Mr Hillman to open the hearing with a history to the case.

Background to the case

P was described as a man in his 40s with complex medical needs after suffering a range of serious injuries due to impulsive behaviour in the context of alcohol and drug abuse.

We were told that in 2016 P drank highly corrosive hydrogen peroxide resulting in oesophagectomy (removal of part of his oesophagus), splenectomy (remove of spleen), tracheostomy and a colostomy with PEJ (percutaneous feeding tube into the small intestine).

He has significant communication difficulties as a result of his tracheostomy and cannot talk, save for mouthing words. He also has a history of seizures, and his situation was further complicated in August 2019 when a severe fit triggered a diffuse hypoxic brain injury. This affected his cognitive function along with reducing his fine motor skills.

He had previously been assessed by a consultant clinical psychologist in November 2020 who reported that P had an Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder, Impulsive Type[1], which had been exacerbated by the acquired brain injury. He also assessed P as lacking capacity in a number of respects, including to litigate and to decide on his residence and care – although in a further report in February 2021 he noted P did have capacity to decide whether or not to accept his PEJ feed and the care associated with this.

There had been considerable difficulties finding an onward placement for P, primarily (it was said) as a result of his need for a tracheostomy and what were described as his “challenging behaviours”. These were reported to include violent assaults on care and medical staff, fire-raising, removing his tracheostomy cuff, and also refusing to allow himself to be PeJ fed (his weight dropping to just 42 kilos at one stage).

P remains in hospital, despite having been ready for discharge since the end of 2019. Two placements in specialist care facilities had broken down (in January and July 2020) as a result of the units being unable to manage his challenging behaviour and so he was returned to hospital to await a suitable placement. Many enquiries had been made, but reportedly many potential placements had declined to accept P, saying they could not deal with the range of needs with which he presents.

On 19th January 2021, the court was told that P was awaiting a move to a planned rehabilitation placement specialising in brain injury, mental health and challenging behavioural needs. This has still not happened. The placement has not explicitly refused to accept him, but there had initially been delays because of the pandemic and lack of staff availability and more recently a succession of subsequent delays as the placement wanted a number of issues addressed in relation to the safe management of P’s needs. This has led, said Roger Hillman (on behalf of the Hospital Board) to “a loss of faith as to whether [Placement] is ever, in reality, going to accept P as a patient“.

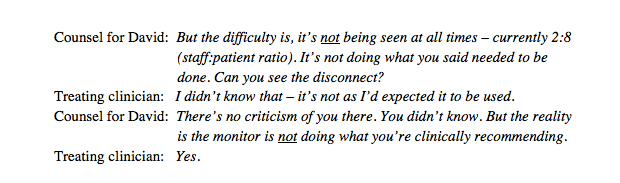

Two days before the hearing I observed, the court had been told that a key part of the problem with finding a suitable placement was the need for safe management of P’s tracheostomy – which he had pulled out in May 2021 and had since refused to have replaced.

The Hospital Board had assumed that the tracheostomy needed to be replaced. But counsel on behalf of P had not had sight of any capacity assessment or best interests analysis about this – and as it turned out, much of the hearing I observed concerned whether or not there was in fact a medical need for the tracheostomy.

Does P need a tracheostomy?

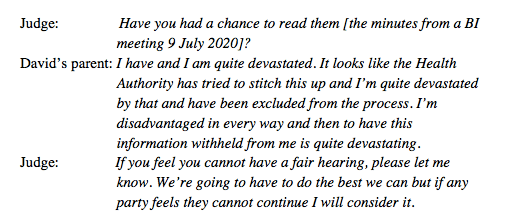

At the hearing just days earlier, it appeared that the position of the healthcare provider had been that there was a clinical need to replace the tracheostomy. However, P’s partner had indicated to the judge that she had heard different opinions about this from the junior doctors, and this led the judge to order a formal report on the matter.

Since the previous hearing, the healthcare provider had sought the opinion of a consultant otolaryngologist, who had advised that the tracheostomy was not necessary.

This was hugely significant, as this might lead to a change in opinion of various placements that had previously felt unable to accept P.

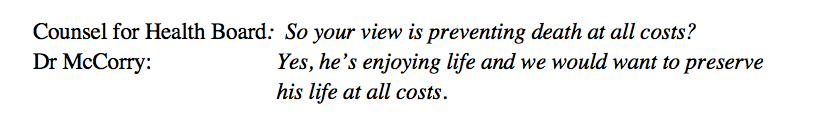

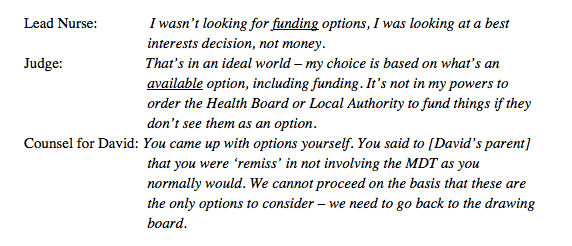

This revelation spurred the first of many challenges from Hayden J:

“On Monday I was told that, given the challenges regarding the tracheostomy, there was probably nowhere in the country that would have him. It now seems, if I have got this right, that the many months of delay resulting from questions and concerns about the tracheostomy from [Placement] were all predicated on the assumption that the tracheostomy is needed. And now it emerges that it isn’t. Such muddle and confusion in a case before the High Court gives me cause for anxiety, and a particular anxiety that P is not being well-served. It’s difficult to see, Mr Hillman, without meaning to press you, how you could not concede the very significant degree of muddle.[2]”

Addressing Mr Brownhill (Counsel for P) Hayden J said “You must have been very surprised by [Consultant’s] report”. “Very surprised indeed,” he replied, “there was a palpable shock when we read it.”

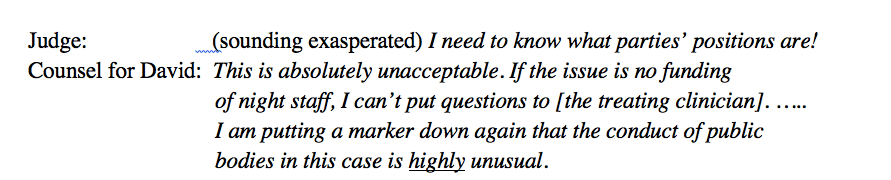

The court heard evidence from the consultant otolaryngologist who had provided the new opinion regarding the need for tracheostomy, from the senior matron caring for P, and from P himself (although public observers were asked to leave while Hayden J spoke with him privately). It appeared there had been considerable breakdown in communications between different healthcare professionals in this case, with Hayden J noting “it is rare to see a breakdown on such scale”.

“If P had not decided to take his tracheostomy out himself, it would still be in. And it’s not needed. And with it in, he cannot communicate with his partner or the outside world, and it has undoubtedly skewed the options for rehabilitation. I consider that to be pretty alarming.” (Hayden J)

However, towards the end of the hearing, P’s partner (who had been present throughout) raised a note of caution and asked for it to be “on record that I still have grave concerns about the tracheostomy. [Consultant] said there would be a very low risk without it, but my understanding is ….” She then gave a fairly detailed account of P’s medical history, including the fact that he “barely has any oesophagus left”: She said “he’s had his whole stomach removed as well, so the swallow has nowhere to go apart from into the lungs. Is [Consultant] aware of that?” The judge reassured her that “what I want to happen now is a proper analysis of all these issues, so that we have a better picture of how his different clinical needs interrelate.”

To the barristers, the judge said that there “were features of [Consultant’s] evidence with which I could have been more comfortable than I was, but he only saw P once, he didn’t have access to the full medical records, and had relatively compromised recollection of the patient he saw”. The medical necessity for the tracheostomy needs to be checked “so that [P’s partner] and I can be reassured”. He added: “I don’t know what his needs are for the future. And the fact that I don’t know is what is worrying me”.

“A very significant degree of muddle”: My reflections

Listening to the contributions, a number of factors stood out as contributing to the catastrophic breakdowns in communication.

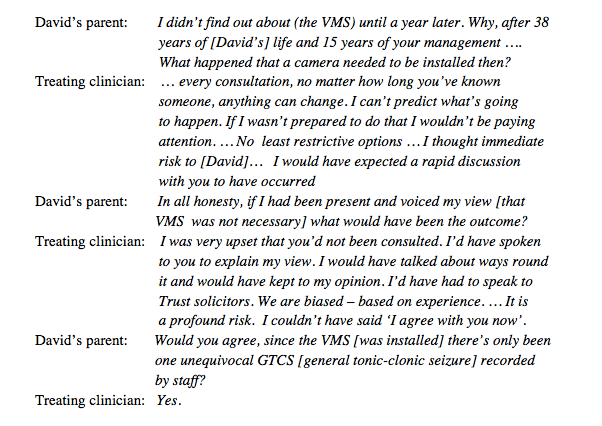

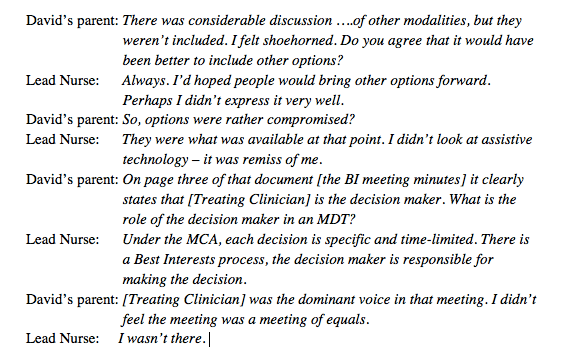

The presence of P’s tracheostomy meant he could not speak, and the nursing evidence made clear that this was inextricably linked with behaviours that challenged the care staff. Since he had removed the tracheostomy, there had been a marked improvement in his engagement with care: the judge referred to him as “blossoming and restored to communication with the world”.

“In the first few months his behaviour could be very challenging. I think initially he was very low in mood, and he was not complying with the recommendation of the nursing and medical team in relation to feeds. … Being able to talk, he’s changed significantly. Being able to communicate he’s been laughing and joking with the staff. He’s feeling more confident in himself. His frustration really was not being able to communicate. His whole impression about how his life is going to be able to move forward has completely changed.” (Matron)

Mr Justice Hayden asked whether anyone has told P that he doesn’t have to have a tracheostomy, but none of those in the courtroom at the time knew the answer to that question.

During the lunch break, the judge visited P via the video-platform: “I told P that he was not going to be required to have a tracheostomy. It was fairly obvious to me that he did not know this. He responded with obvious enthusiasm and put his thumb up to me in a celebratory gesture.” (Hayden J)

It was subsequently reported to the court that P was “very, very pleased that you included him in this discussion and was smiling considerably. ‘Very chuffed’ were his words.”

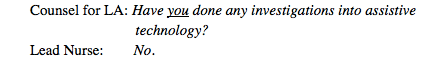

One does not need to be a psychologist to appreciate that a person who cannot communicate through usual means will seek to do so by whatever means are available to them. In P’s case, he communicated his frustrations by controlling his nutritional status and rejecting care. It was not clear what (if any) efforts had been made to establish alternative, reliable communication methods with him. P was noted to use a tablet to watch Netflix and listen to music; I was left with many questions about whether this had or could have been used to support better communication at an earlier stage.

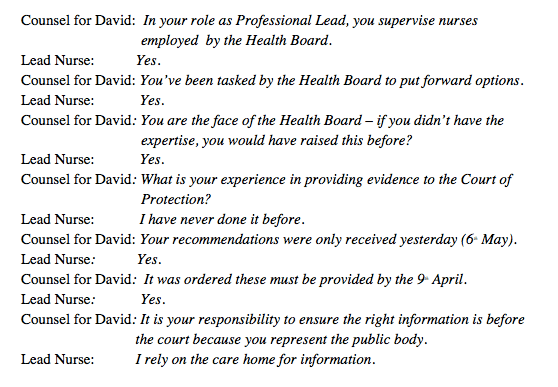

There were also systemic, organisational factors at play. P was noted to have been admitted under the care of a medical consultant, but was being cared for on a surgical ward due to his tracheostomy needs. As such, he was an ‘outlier’ on the ward. He had then been identified as medically fit for discharge, and therefore it appeared there was no-one genuinely ‘leading’ on his physical healthcare needs. Possibly as a consequence, it was clear that different professionals on the ward held and expressed different views on what was required. This was a point Hayden J pushed on repeatedly whilst hearing evidence, highlighting the impact this was having on P and his partner’s understanding of their situation and the medical plans for his care.

Later in the hearing, it was mentioned that P was being cared for on the ward under the auspices of the Mental Health Act 1983; but no reference was made to involvement from mental health professionals in supporting his mood or behaviour. This begged the question in my mind as to how and why his psychological needs appeared to have been so overwhelmingly ignored by mental health provision, apparently being left to the nursing team to work through without a clear formulation. I wondered whether P’s complex psychological needs (which included emotional and cognitive issues as well as self-harming behaviours) had led to an over-shadowing of his ‘normal’ distress in the face of unwelcome healthcare interventions and his right to have an opinion about these. There was a sense that he had been silenced in his care, both literally and metaphorically; I felt distressed reflecting on the many ways that being silenced in this way would be experienced by any person who had been through significant trauma. It was apparent that P’s opinion had not been weighted highly in decisions made about him- if, indeed, any such best interests decisions were in fact needed. At one point Hayden J commented: “Without wishing to put myself in the place of the professionals … I did not feel I was interacting with a man who showed obvious incapacity on the key issues we are dealing with here” (we could see Matron clearly nodding as he said this).

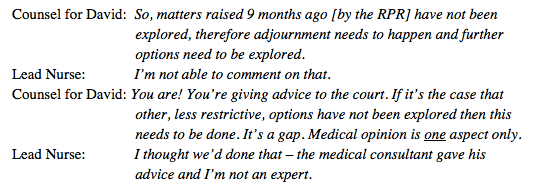

I also wondered if the teams involved had become so paralysed by the complexities that their usual practices had fallen aside. Capacity assessments four months earlier had deemed P to lack capacity to litigate, and to make decisions about care and treatment, but reference was made to this conclusion being somewhat “broad brush” (and it did not seem that there was any capacity evidence relating to the tracheostomy in particular). I wondered whether due consideration had been given during those assessments to the fact that specific decisions in P’s care and treatment would vary greatly in their cognitive complexity, emotional salience, medical necessity and so on. No reference was made at any point to any efforts made by the treating team to support P’s capacity for these decisions. I wondered why it did not appear that anyone was considering whether to re-assess now that P was presenting so very differently. I was relieved at the end of the hearing when Hayden J ordered updated capacity assessments.

Overall, I was struck by what appeared to be a complete absence of a holistic formulation of P’s needs. I noticed how angry I felt about this – the absence of what to me is a basic tenet of quality care for people with complex needs.

The compassion demonstrated by the nursing team working with P, and their persistence in caring for him in the face of complexity, was not enough. Nor was the absolute dedication and support provided by his partner, on which Hayden J repeatedly commented. Their care needs to support from a robust plan in which each involved professional understands the ‘big picture’ and how their involvement with P connects to other aspects of his care. This seems as far from the reality on the ground as could be imagined.

Hayden J expressed similar views, noting that what was needed was to go “back to the drawing board”. The way P had been described to potential care providers was now out of date.

“This is a relatively young man in hospital, showing at long last some resilience to his situation, some real improvements in his weight, his general demeanour is better and the clinical consensus is that although he’s still far from an easy man, he’s unrecognisably milder and more manageable than 9 months ago.” (Hayden J)

What was needed was to start with a “complete blank sheet” and to urgently reassess all of P’s needs and then formulate a care plan to meet them. This would then form the basis for suitable placements to be identified. Mr Justice Hayden advocated for a clinical lead to be appointed to oversee this process, with the aim of P having “…a plan that enables him to take advantage of his own advances…”.

On a few occasions Hayden J appeared to wonder aloud if his expectations (for clinical leadership, multi-disciplinary reviews, and so on) were unrealistic. My first reaction was absolutely not: these are basic principles of effective care and rehabilitation. I then connected with my own experiences of healthcare (as a recipient, carer, clinician, manager) in both NHS and independent sector contexts, acknowledging the frequency with which less than ideal practice occurs. We can so readily move to place the fault with individuals. This is simple, but wrong. Healthcare staff face increasing demand and complexity, in the absence of increased funding and effective systems and processes. These challenges were present before the pandemic, and have been exacerbated by it. The time to properly consider complex issues is increasingly squeezed away. In such rationed contexts, lines are drawn: we will do this, we won’t do that. And into the gaps between these lines can fall people like P.

Holding these reflections in mind, I welcomed Hayden J’s comments that the hearing had been “in some ways quite a disturbing experience”. It was reassuring to me that those who hear such stories regularly are not immune to the emotions they evoke. He noted that he would not be making criticisms in a written judgment at this point, as he wished to keep the focus on P’s needs, but this would certainly not preclude him from doing so in future.

The skill with which Hayden J communicated with all parties, highlighting weaknesses to be addressed without meandering into unnecessarily assigning blame, such that all parties could remain focused on P, was remarkable to witness. In effect, he modelled the role that the proposed clinical lead would need to take. Nevertheless, it seemed clear he would not countenance any further lack of action on the part of the healthcare provider. I left the hearing with a profound sense of gratitude that there are those who will advocate with absolute clarity for the rights of P to be respected, and to promote his quality of life going forwards.

Dr Gaby Parker is a Consultant Clinical Neuropsychologist with Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust, and has an independent medicolegal practice with Allied Neuro Therapy Ltd. She has a specialist interest in complex interdisciplinary community neurorehabilitation and mental capacity following acquired brain injuries. She tweets @gabyvparker

[1] It is acknowledged that many people with lived experience and/or who practice within mental health fields disagree with the use of ‘personality disorder’ to describe psychological experiences. It is included here as this was the term used during the hearing. For further commentary on the use of ‘personality disorder’ within the COP, see Keir Harding’s contribution to the Open Justice blog: What does the Court of Protection need to know about “borderline personality disorder”? – Promoting Open Justice in the Court of Protection (openjusticecourtofprotection.org)

[2] We are not permitted to audio-record hearings, so quotations are based on notes taken at the time and are unlikely to be verbatim. They are as close as possible to what was said. My thanks to Celia Kitzinger who supplied these direct quotes.

Image by Hans-Peter Gauster via Unsplash